Biddenden Maids

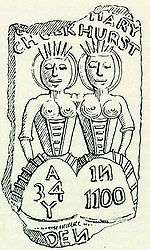

Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst (or Chalkhurst), commonly known as the Biddenden Maids, were a pair of conjoined twins supposedly born in Biddenden, Kent, England, in the year 1100. They are said to have been joined at both the shoulder and the hip, and to have lived for 34 years. It is claimed that on their death they bequeathed five plots of land to the village, known as the Bread and Cheese Lands. The income from these lands was used to pay for an annual dole of food and drink to the poor every Easter. Since at least 1775, the dole has included Biddenden cakes, hard biscuits imprinted with an image of two conjoined women.

Although the annual distribution of food and drink is known to have taken place since at least 1605, no records exist of the story of the sisters prior to 1770. Records of that time say that the names of the sisters were not known, and early drawings of Biddenden cakes do not give names for the sisters; it is not until the early 19th century that the names "Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst" were first used.

Edward Hasted, the local historian of Kent,[1] has dismissed the story of the Biddenden Maids as a folk myth, claiming that the image on the cake had originally represented two poor women and that the story of the conjoined twins was "a vulgar tradition" invented to account for it, while influential historian Robert Chambers accepted that the legend could be true but believed it unlikely. Throughout most of the 19th century little research was carried out into the origins of the legend. Despite the doubts among historians, in the 19th century the legend became increasingly popular and the village of Biddenden was thronged with rowdy visitors every Easter. In the late 19th century historians investigated the origins of the legend. It was suggested that the twins had genuinely existed but had been joined at the hip only rather than at both the hip and shoulder, and that they had lived in the 16th rather than the 12th century.

In 1907, the Bread and Cheese Lands were sold for housing, and the resulting income allowed the annual dole to expand considerably, providing the widows and pensioners of Biddenden with cheese, bread and tea at Easter and with cash payments at Christmas. Biddenden cakes continue to be given to the poor of Biddenden each Easter, and are sold as souvenirs to visitors.

Legend

According to tradition Mary and Eliza Chulkhurst,[2] or Chalkhurst,[3] were born to relatively wealthy parents in Biddenden, Kent, in the year 1100.[2] The pair were said to be conjoined at both the shoulder and the hip.[4] They grew up conjoined, and are said to have "had frequent quarrels, which sometimes terminated in blows".[5] At the age of 34, Mary Chulkhurst died suddenly. Doctors proposed to separate the still-living Eliza from her sister's body but she refused, saying "as we came together we will also go together", and died six hours afterwards.[6] In their wills, the sisters left five pieces of land in the Biddenden area comprising around 20 acres (8 ha) in total to the local church,[7] with the income from these lands (claimed to have been 6 guineas per annum at the time of their death) to provide an annual dole of bread, cheese and beer to the poor every Easter.[6] Henceforward, the lands were to be known as the Bread and Cheese Lands.[6]

History

The churchwardens of Biddenden continued to maintain the annual dole from the Bread and Cheese Lands. It is recorded that in 1605, the custom that "on that day [Easter] our parson giveth unto the parishoners bread, cheese, cakes and divers barrels of beer, brought in there and drawn" was suspended on account of a visit from Charles Fotherby, the Archdeacon of Canterbury, owing to previous ceremonies having caused "much disorder by reason of some unruly ones, which at such time we cannot restrain with any ease".[6] In 1645, rector William Horner claimed that the Bread and Cheese Lands were glebe (land intended for the use of the parish priest), and attempted to take control of the lands.[6] The case of the Bread and Cheese Lands was brought before the Committee for Plundered Ministers, who eventually found in favour of the charity in 1649.[6] Horner brought the case before the Court of the Exchequer in 1656 but again without success, and the charity continued to own the lands and to operate the annual Easter dole.[6][1] Witness statements from these cases mention that the lands had been given by two women "who grew together in their bodies", but do not give any name for the women.[8]

In 1681 the "disorder and indecency" of the annual dole led to the threat of intervention by the Archbishop of Canterbury.[5] The distribution of the dole ceased to be conducted inside the church; it was moved to the church porch.[9][note 1]

By 1770, it is recorded that the annual dole took place immediately after the afternoon Easter service. The annual income from the Bread and Cheese Lands had risen to 20 guineas (about £2,600 in 2016), and a huge quantity of food was distributed each year.[12][13][note 2] By this time as well as the dole of bread, cheese and beer, hard bread rolls known as "Biddenden cakes", moulded into an image of the sisters, were thrown to crowds from the church roof.[5][12] The Biddenden cakes were flat, hard and made of flour and water,[5] and were described as "not by any means tempting";[14] one writer in 1860 described one as "a biscuit plaque".[15]

Origins of the Biddenden Maids legend

Although it is known that the charity had been in operation as early as 1656,[16] an anonymous article in The Gentleman's Magazine in August 1770 is the earliest recorded account of the legend of the Biddenden Maids.[17][note 3] This account states that the twins were joined at the hip only, rather than at both the hip and the shoulder, and that they lived to a relatively old age.[12][18] The article explicitly states that their names were not recorded, and that they were known only as the "Maids of Biddenden".[12] The anonymous author recounts the story of their bequest of the lands to the parish to support the annual dole, and goes on to say that despite the antiquity of the events described, he has no doubt as to their authenticity.[12] As with all accounts of the tradition prior to 1790 the author does not mention their alleged birth in 1100, or the name of Chulkhurst; these details first appeared in a broadside published in 1790.[19] The Antiquarian Repertory of 1775 says that the sisters had lived "as tradition says, two hundred and fifty years ago".[20] Drawings of Biddenden cakes from this period show that they featured an image of two women, possibly conjoined, but no names, dates or ages.

Historian Edward Hasted, in the third volume of The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent published in 1798, dismissed the legend of the Biddenden Maids. He claimed that the Bread and Cheese Lands were the gift of two women named Preston (although he elsewhere described the lands as having been "given by persons unknown").[1][note 4] Hasted stated that the Biddenden cakes had only begun to be moulded with the imprint of two women in the last 50 years (i.e. since 1748) and that the figures were intended to represent "two poor widows, as the general objects of a charitable benefaction".[1] While he mentioned a legend that the figures represent two conjoined twins who died in their 20s and bequeathed the Bread and Cheese Lands to the parish, he dismissed it as "a vulgar tradition".[1][note 5]

Hasted's arguments were largely accepted by influential historian Robert Chambers,[24] and the story was generally treated as a folk myth.[note 6] A letter to the British Medical Journal in 1869 pointed out that surnames were not in use in Kent in the 12th century, and that in older styles of English handwriting the 1 and 5 characters could easily be confused, and suggested a correct birthdate of 1500.[26] The Biddenden Maids were occasionally mentioned in pieces on conjoined twins, particularly after Chang and Eng Bunker proved that conjoined twins could live to an advanced age and lead relatively normal lives.[27] Notes and Queries magazine called in 1866 for a close examination of Biddenden documents, the editors describing Hasted's conclusions as "very obscure and unsatisfactory" and questioning why the names "Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst" should have been added to the design of cakes granted by a family named Preston,[28] but no significant research into the tradition was carried out.[27]

Growth of the charity

.jpg)

As the annual dole grew larger the Easter distribution became increasingly popular. In 1808 a broadside featuring a woodcut of the twins and a brief history of their alleged story was sold outside the church at Easter,[4] the first recorded mention of the names "Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst",[17] and clay replicas of Biddenden cakes were sold as souvenirs.[5]

A Short but Concise account of Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst

who were born joined together by the Hips and Shoulders

In the year of our Lord 1100 at Biddenden in the County of Kent, commonly called

The Biddenden Maids

The reader will observe by the plate of them, that they lived together in the above state Thirty-four years, at the expiration of which time one of them was taken ill and in a short time died; the surviving one was advised to be separated from the body of her deceased Sister by dissection, but she absolutely refused the separation by saying these words—"As we came together we will also go together,"—and in the space of about Six Hours after her Sister's decease she was taken ill and died also.

By their will they bequeath to the Churchwardens of the Parish of Biddenden and their successors Churchwardens for ever, certain Pieces or Parcels of Land in the Parish of Biddenden, containing Twenty Acres more or less, which now let at 40 Guineas per annum. There are usually made, in commemoration of these wonderful Phenomena of Nature, about 1000 Rolls with their Impression printed on them, and given away to all strangers on Easter Sunday after Divine Service in the Afternoon; also about 500 Quartern Loaves and Cheese in proportion, to all the poor Inhabitants of the said Parish.[1][note 1]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

N.26Q_Folk_Lorewas invoked but never defined (see the help page).- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hastedwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Cite error: There are<ref group=note>tags on this page, but the references will not show without a{{reflist|group=note}}template (see the help page).

In the 1820s, a new account of the Biddenden Maids was published, which claimed that a gravestone marked with a diagonal line near the rector's pew in Biddenden church was the sisters' burial place.[5][note 7] In 1830 it was noted that Biddenden was becoming thronged by visitors every Easter, "attracted from the adjacent towns and villages by the usage, and the wonderful account of its origin, and the day is spent in rude festivity".[29] The large crowds were increasingly disorderly, and churchwardens on occasion had to use their staffs to hold back the mob.[17] As a result, the distribution of the dole was moved from the church to the workhouse, but the crowds continued to cause problems.[30] In 1882 Biddenden's rector applied for authority to abandon the ceremony; the Archbishop of Canterbury permitted the distribution of bread, cheese and Biddenden cakes to continue, but abolished the free beer in an effort to combat the problem of unruly crowds.[30]

In 1900, antiquarian George Clinch investigated the Biddenden Maids in detail.[31] Examining the costumes of the figures on the Biddenden cake moulds, he concluded that the style of dress depicted dated from the reign of Mary I (1553–1558), a date roughly consistent with the "two hundred and fifty years ago" reported in 1775, and concluded that the tradition had originated in the 16th century.[32][note 8] He suggested that the "1100" date on Biddenden cakes had originally read "1500",[20] and explained the absence of names on prints of 18th century Biddenden cakes as an engraving error.[32] It is likely that the cake moulds examined by Clinch were not the original moulds, as the designs Clinch examined are strikingly different to the earliest surviving drawings of Biddenden cakes, published in 1775.[31] Writing in the early 1930s, William Coles Finch explains the confusion over the dates, saying "the old-fashioned numeral five is so frequently taken as a one". He lamented the quality of the Biddenden cake then being produced, compared to that of former years. Coles Finch stated that the villagers considered the then-current cake to be unleavened bread.[33]

Belief and scepticism

In almost all drawings and Biddenden cake designs, the twins are shown as conjoined at both the hip and the shoulder. Although such a fusion is theoretically possible, in that twins fused at one point may form a secondary fusion elsewhere, no case of a viable double fusion has ever been documented.[34]

Although Clinch believed that the evidence pointed to the twins having genuinely existed but that they had lived in the 16th century, rather than the early 12th century as generally claimed, they are not mentioned in any journals or books from the period.[35] This points against their having lived in the 16th century; the case of Lazarus and Joannes Baptista Colloredo (1617 – after 1646) had prompted great interest in conjoined twins, and conjoined sisters surviving to adulthood in south east England would have been widely noted.[36]

In 1895, surgeon J. W. Ballantyne considered the case of the Biddenden Maids from a teratological perspective. He suggested that they had in fact been pygopagus (twins joined at the pelvis).[36] Pygopagus twins are known to put their arms around each other's shoulders when walking, and Ballantyne suggested that this accounted for their apparently being joined at the shoulders in drawings.[37] The pygopagus Millie and Christine McCoy had lived in Britain for a short time before going on to a successful singing career in the United States, and it was known from their case that such twins were capable of surviving to adulthood.[38][note 9]

Jan Bondeson (1992 and 2006) proposed that, while the names "Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst" are not recorded in any early documents and are likely to have been a later addition,[36] the existence of the twins and the claimed 1100 year of birth cannot be dismissed.[36][40] Although mediaeval chronicles are unreliable, he noted multiple reports in the Chronicon Scotorum, the Annals of the Four Masters and the Annals of Clonmacnoise of a pair of conjoined sisters born in or around 1100, although all three are records of Irish history and none mention Kent as the location.[41] He concluded that the case of Christine McCoy, who survived for eight hours following the death of her polypagus twin Millie, shows that the claimed six hours between the deaths of the Biddenden Maids is plausible,[42] and agreed with Ballantyne's proposal that the idea that the twins were joined at the shoulder is a later misinterpretation of the figures on the Biddenden cake.[25] He also pointed out that although there is no recorded version of the legend prior to 1770, there would have been no possible motive for the villagers of the 18th century to fabricate the story.

Today

In 1907, the Chulkhurst Charity was amalgamated with other local charities with similar purposes, to form the Biddenden Consolidated Charity,[10] still functioning as a registered charity.[43] The Bread and Cheese Lands were sold for housing,[note 10] expanding the charity significantly to provide Biddenden pensioners and widows with bread, cheese, and tea at Easter, a cash payment at Christmas, and distribute Biddenden cakes.[21] (During the food rationing of the 1940s and early 1950s, the cheese was replaced by cocoa.[44] Distribution of cheese resumed in 1951.[45]) A wrought iron village sign showing the Biddenden Maids was erected on Biddenden village green in the 1920s.[21]

The tradition of the dole continues to the present, and every Easter Monday tea, cheese and bread are given to local widows and pensioners through the windows of Biddenden's former workhouse.[46] All those eligible for the annual dole are given a Biddenden cake, and they are sold as souvenirs to visitors.[10] The cakes are baked so hard as to be inedible, to allow better preservation as souvenirs;[17] they are baked in large batches every few years and kept until the stock runs out.[10] Historically, the loaves used were of the archaic quartern loaf size, but this particular part of the tradition ended when Biddenden's last bakery closed in the 1990s.[21]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The Pitt Rivers Museum claims that Biddenden church at one time featured a stained glass window depicting the Biddenham Maids, citing a purported poem found in "old charity documents" as evidence, which supposedly read The moon on the east side oriel shone / Through slender shafts of shapely stone / The silver light, so pale and faint / Shewed the twin sisters and many a saint / Whose images on the glass were dyed / Mysterious maidens side by side / The moon beam kissed the holy pane / And threw on the pavement a mystic stain.[10] This is in fact an extract from Walter Scott's 1805 The Lay of the Last Minstrel, describing Melrose Abbey; the line given as "Shewed the twin sisters and many a saint" reads Show'd many a prophet and many a saint in the original.[11]

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Measuring Worth: UK CPI. The rural Kent economy in this period was based on tenant farming and involved significant amounts of barter and payment in kind. Consumer pricing does not translate accurately into modern equivalents; 2016 equivalent prices should be treated as a very rough guide only.

- ↑ It has been claimed that an account of the Maids was published in 1660, but this is believed to be a later addition which was pasted into the 1660 book.[17]

- ↑ No family named Preston is recorded as having lived in or near Biddenden during the period in question. Records exist of a family named Chulkhurst living in Biddenden in the 17th and 18th centuries.[21]

- ↑ Hasted was an expert on genealogy and topography but knew little about folklore and local tradition, and later critics have often been sceptical regarding his accuracy, especially regarding social and biographical history.[19][22] His contemporary (and Member of Parliament for nearby Maidstone) Samuel Egerton Brydges described him as "a little, mean-looking man, with a long face and a high nose; quick in his movements, and sharp in his manner: he had no imagination or sentiment; nor any extraordinary quality of the mind, except memory."[23]

- ↑ Although later writers have stated that Chambers accepted Hasted's arguments and dismissed the legend of the conjoined twins out of hand,[25] unlike Hasted, Chambers accepted that the legend was potentially true.[24] He concluded that in the absence of any evidence for the sisters having existed, on the balance of probabilities the figures on the Biddenden cake were more likely to represent "the general objects of a charitable benefaction" and that the story of the twins was likely to be a folk myth created to explain the unusual design of the cakes.[24]

- ↑ One source claims that the sisters were taken to the monks at Battle Abbey and that they were buried in Hastings, but there is no evidence for this.[17] (No grave is visible near the rector's pew, but the church organ is situated in the site described and it may cover the grave.[13]).

- ↑ The point about the style of dress depicted on the cakes being that of the 16th, not the 12th, century had previously been made by an anonymous contributor to Notes and Queries in 1856.[4]

- ↑ Millie and Christine McCoy, born into slavery in Columbus County, North Carolina in 1851, lived into their 60s and enjoyed a successful musical career under the stage name of "The Two Headed Nightingale". They were particular favourites of Queen Victoria, who met with them each time they toured England. They retired wealthy in 1900, dying of tuberculosis in 1912.[39]

- ↑ The Bread and Cheese Lands are today occupied by housing, known as the Chulkhurst Estate,[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hasted, Edward (1798), "Parishes: Biddenden", The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, British History Online: 130–141

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, pp. 237–238.

- ↑ What are conjoined twins?, BBC, archived from the original on 5 November 2010, retrieved 15 October 2010

- 1 2 3 "Cheverells" (22 November 1856), "Folk Lore", Notes and Queries, London: Chappell & Co: 404–405

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bondeson 1992, p. 217.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bondeson 2006, p. 238.

- ↑ Jerrold 1914, p. 218.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 258.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, pp. 238–239.

- 1 2 3 4 Imaging of the Biddenden Maids, Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum, archived from the original on 27 December 2010, retrieved 13 October 2010

- ↑ Scott 1855, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Urban 1770, p. 372.

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 239.

- ↑ Sharpe 1846, p. 413.

- ↑ "Leicester Agricultural and Archæological Society", The Ecclesiologist, Cambridge: Cambridge Camden Society, 27 (66): 388, December 1860

- ↑ "Home". Biddenden Parish Council. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bondeson 1992, p. 218.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, pp. 241–242.

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 242.

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bondeson 2006, p. 241.

- ↑ Jerrold 1914, p. 219.

- ↑ Timbs 1834, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 Chambers 1863, p. 427.

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 257.

- ↑ Heaton, J. D. (17 April 1869), "United Twins", British Medical Journal, London: British Medical Association, 1869 (1): 363

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 243.

- ↑ Lloyd, George (10 February 1866), "Chulkhurst: The Biddenden Maids", Notes and Queries, London: Chappell & Co: 122

- ↑ Hone 1830, p. 445.

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 240.

- 1 2 3 Bondeson 1992, p. 219.

- 1 2 Bondeson 2006, p. 244.

- ↑ Coles Finch 1933, p. 92.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 246.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 Bondeson 1992, p. 220.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 247.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 248.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, pp. 248–249.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 259.

- ↑ Bondeson 1992, p. 221.

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, pp. 249–50.

- ↑ Charity Commission. Biddenden Consolidated Charity, registered charity no. 209504.

- ↑ "An Old Kent Charity". News in Brief. The Times (51662). London. 11 April 1950. col D, p. 3. (subscription required (help)). (subscription required)

- ↑ "Cheese Charity Resumed". News in Brief. The Times (51959). London. 27 March 1951. col C, p. 2. (subscription required (help)). (subscription required)

- ↑ Bondeson 2006, p. 237.

Sources

- Bondeson, Jan (April 1992), "The Biddenden Maids: a curious chapter in the history of conjoined twins", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, London: Royal Society of Medicine Press, 85 (4): 217–221, PMC 1294728

, PMID 1433064

, PMID 1433064 - Bondeson, Jan (2006), Freaks: The Pig-Faced Lady of Manchester Square & Other Medical Marvels, Stroud: Tempus Publishing, ISBN 0-7524-3662-7

- Chambers, Robert (1863), The Book of Days, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co

- Coles Finch, William (1933), Watermills and Windmills, London: C W Daniel Company

- Hone, William (1830), The Every-Day Book, London: Thomas Tegg

- Jerrold, Walter (1914), Highways and Byways in Kent, London: Macmillan & Co

- Scott, Walter (1855), The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott, Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company

- Sharpe, T. B. (25 April 1846), "Old and Popular customs", Sharpe's London Magazine, London: T. B. Sharpe, 1 (26): 413

- Timbs, John (2 August 1834), "Autobiography of Sir Egerton Brydges, Bart", The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, London: J. Limbird, 24 (675)

- Sylvanus Urban (Edward Cave), ed. (August 1770), "Of Biddenden in Kent", The Gentleman's Magazine, London: D. Henry, 40

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Biddenden Maids. |

- Biddenden Parish Council

- Biddenden cakes exhibited at London's Science Museum