Meropenem

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Merrem |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV |

| ATC code | J01DH02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% |

| Protein binding | Approximately 2%. |

| Biological half-life | 1 hour |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

119478-56-7 |

| PubChem (CID) | 441130 |

| DrugBank |

DB00760 |

| ChemSpider |

389924 |

| UNII |

FV9J3JU8B1 |

| KEGG |

D02222 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:43968 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL127 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.170.691 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

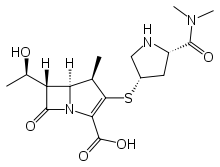

| Formula | C17H25N3O5S |

| Molar mass | 383.464 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Meropenem is an ultra-broad-spectrum injectable antibiotic used to treat a wide variety of infections. It is a β-lactam and belongs to the subgroup of carbapenem, similar to imipenem and ertapenem. Meropenem was originally developed by Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma.[1][2] It gained US FDA approval in July 1996. It penetrates well into many tissues and body fluids, including cerebrospinal fluid, bile, heart valve, lung, and peritoneal fluid.[3] It was initially marketed by AstraZeneca under the trade name Merrem.

Mechanism of action

Meropenem is bactericidal except against Listeria monocytogenes, where it is bacteriostatic. It inhibits bacterial wall synthesis like other β-lactam antibiotics. In contrast to other beta-lactams, it is highly resistant to degradation by β-lactamases or cephalosporinases. In general, resistance arises due to mutations in penicillin-binding proteins, production of metallo-β-lactamases, or resistance to diffusion across the bacterial outer membrane.[4] Unlike imipenem, it is stable to dehydropeptidase-1, so can be given without cilastatin.

Indications

The spectrum of action includes many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (including Pseudomonas) and anaerobic bacteria. The overall spectrum is similar to that of imipenem, although meropenem is more active against Enterobacteriaceae and less active against Gram-positive bacteria. It works against extended-spectrum β-lactamases, but may be more susceptible to metallo-β-lactamases.[3] Meropenem is frequently given in the treatment of febrile neutropenia. This condition frequently occurs in patients with hematological malignancies and cancer patients receiving anticancer drugs that cause bone marrow suppression. It is approved for complicated skin and skin structure infections, complicated intra-abdominal infections, and bacterial meningitis.

Administration

Meropenem must be administered intravenously. It is supplied as a white crystalline powder to be dissolved in 5% monobasic potassium phosphate solution. Dosing must be adjusted for altered kidney function and for haemofiltration.[5]

Common adverse effects

The most common adverse effects are diarrhea (4.8%), nausea and vomiting (3.6%), injection-site inflammation (2.4%), headache (2.3%), rash (1.9%), and thrombophlebitis (0.9%).[4] Many of these adverse effects were observed in the setting of severely ill individuals already taking many medications including vancomycin.[6][7] One study showed Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea happened in 3.6% of the patients on meropenem.[8] Meropenem also has a reduced potential for causing seizures in comparison with imipenem. Several cases of severe hypokalemia have been reported.[9][10] Meropenem, like other carbopenems, is a potent inducer of multidrug resistance in bacteria.

Trade names

Other trade names include Penmer by Biocon (India), Merosan By Sanbe Farma, Merobat by Interbat and Merofen by Kalbe (Indonesia), Merofit (India), Merocil by Pharmacil (Bangladesh), Meronir by Nirlife (India), Merowin by Strides Acrolab (India), Aktimer by Aktimas Biopharmaceuticals (India), Zwipen, Carbonem, Ronem (Opsonin Pharma, BD), Neopenem by Neomed (India), Mepem (Taiwan), Meropen (Japan, Korea), Merem (Australia), Neopenem, Merocon (Continental), Carnem (Laderly Biotech), Penro (Bosch), Meronem (Germany, ICI Pakistan), Meroza (German Remedies), Merotrol (Lupin), and Meromer by Orchid Chemicals, Mexopen (Samarth life sciences in India) and Pharmaceuticals (India), Lykapiper by Lyka Labs (India), Winmero by Parabolic drugs (India), Meronem by AstraZeneca, Mepenox by BioChimico, Meromax by Eurofarma, Zylpen by Aspen Pharma (Brazil), Meropenia by SYZA Health Sciences LLP (India),Ivpenem by Medicorp Pharmaceuticals (India).

References

- ↑ Edwards, JR; Turner, PJ; Wannop, C; Withnell, ES; Grindey, AJ; Nairn, K (February 1989). "In vitro antibacterial activity of SM-7338, a carbapenem antibiotic with stability to dehydropeptidase I". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 33 (2): 215–22. doi:10.1128/AAC.33.2.215. PMC 171460

. PMID 2655530.

. PMID 2655530. - ↑ Creation of Meropenem

- 1 2 AHFS Drug Information (2006 ed.). American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2006.

- 1 2 Mosby's Drug Consult 2006 (16 ed.). Mosby, Inc. 2006.

- ↑ Bilgrami, I; Roberts, JA; Wallis, SC; Thomas, J; Davis, J; Fowler, S; Goldrick, PB; Lipman, J (July 2010). "Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis receiving high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (7): 2974–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.01582-09. PMC 2897321

. PMID 20479205.

. PMID 20479205. - ↑ Erden, M; Gulcan, E; Bilen, A; Bilen, Y; Uyanik, A; Keles, M (7 March 2013). "Pancytopenýa and Sepsýs due to Meropenem: A Case Report" (PDF). Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 12 (1). doi:10.4314/tjpr.v12i1.21.

- ↑ http://www.ehealthme.com/meropenem/meropenem-side-effects

- ↑ Yeung, EYH; Gore JG; Auersperg EV (2012). "A Retrospective Analysis of the Incidence of Clostridium Difficile Associated Diarrhea with Meropenem and Piperacillin-tazobactam" (PDF). International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health. 4 (8): 1567–1576.

- ↑ Margolin, L (2004). "Impaired rehabilitation secondary to muscle weakness induced by meropenem". Clinical drug investigation. 24 (1): 61–2. doi:10.2165/00044011-200424010-00008. PMID 17516692.

- ↑ Bharti, R; Gombar, S; Khanna, AK (2010). "Meropenem in critical care - uncovering the truths behind weaning failure". Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 26 (1): 99–101.

External links

- MERREM I.V. (meropenem for injection) Official Site by AstraZeneca