Minami-Tori-shima

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">南鳥島 Nickname: Marcus Island | |

|---|---|

|

Aerial photo from 1987 | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 24°17′12″N 153°58′50″E / 24.28667°N 153.98056°ECoordinates: 24°17′12″N 153°58′50″E / 24.28667°N 153.98056°E |

| Total islands | 1 |

| Area | 1.332 km2 (0.514 sq mi) |

| Coastline | 6,000 m (20,000 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | no civilian population |

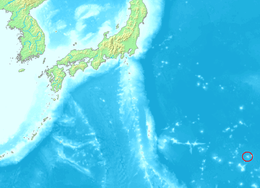

Minami-Tori-shima (南鳥島, "Southern Bird Island"), also known as Marcus Island, is an isolated Japanese coral atoll in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, located some 1,848 kilometres (1,148 mi) southeast of Tokyo and 1,267 kilometres (787 mi) east of the closest Japanese island, South Iwo Jima of the Ogasawara Islands, and nearly on a straight line between mainland Tokyo and the United States' Wake Island, 1,415 kilometres (879 mi) further to the east-southeast. The closest island to Minami-Tori-shima is East Island in the Mariana Islands, which is 1,015 kilometres (631 mi) to the west-southwest. The meaning of its Japanese name is "Southern Bird Island". It is the easternmost territory belonging to Japan, and the only Japanese territory on the Pacific Plate, past the Japan Trench. Although very small (just over 1 km2) and without a civilian population, it is of strategic importance, as it enables Japan to claim a 428,875 square kilometres (165,589.6 sq mi) Exclusive Economic Zone in the surrounding waters. It is also the easternmost territory of Tokyo, being administratively part of Ogasawara village.

Geography

Minami-Tori-shima is triangular in shape, and unusual in that it has a saucer-like profile, with a raised outer rim of between 5 and 9 metres (16 and 30 ft) above sea level. The central area of the island is 1 metre (3 ft) below sea level. Minami-Tori-shima is surrounded by a fringing reef which ranges from 50 to 300 metres (164–984 ft) in width, enclosing a shallow lagoon, which is connected with the open ocean by narrow passages on the southern and northeastern sides. Outside the reef, the ocean depths quickly plunge to over 1,000 metres (3,300 ft). The island has a total land area of 1.2 square kilometres (300 acres). The island also has the highest average temperature in Japan.[1]

History

The first discovery and mention of an island in this area was made by a Spanish Manila Galleon captain, Andrés de Arriola in 1694.[2] It was charted in Spanish maps as Sebastian López, after the Spanish Admiral Sebastian López, victorious in the battles of La Naval de Manila in 1646 against the Dutch. Its exact location was left unrecorded until further sightings in the early 19th century.

The island was mentioned again in 1864 by the ship Morning Star, belonging either to the United States or the Kingdom of Hawaii, and was given the name "Marcus Island". Its position was recorded by a United States survey ship in 1874, and first landed on by a Japanese national, Kiozaemon Saito in 1879. On June 30, 1886, a Japanese named Shinroku Mizutani led a group of 46 colonists from Haha-jima in the Ogasawara Islands to settle on Marcus Island. The settlement was named "Mizutani" after the leader of the expedition. The Empire of Japan officially annexed the island July 24, 1898,[3] the previous United States claim from 1889 according to the Guano Islands Act not being officially acknowledged. The island was officially named "Minami-Tori-shima" and placed administratively under the Ogasawara Subprefecture of Tokyo.

Sovereignty over the island before World War I was apparently disputed as various sources from the time move the island from the American to Japanese domain without specific explanation. In 1902, the United States dispatched a warship from Hawaii to enforce its claims, but withdrew on finding the island still inhabited by Japanese, with a Japanese warship patrolling nearby. In 1914, William D. Boyce included Marcus Island as an obviously American island in his book, The Colonies and Dependencies of the United States. In 1933, by orders of the Japanese government, the civilian inhabitants of Minami-Tori-shima were evacuated. In 1935, the Imperial Japanese Navy established a meteorological station on the island, and built an airstrip.

After the start of World War II the Japanese garrison stationed on the island consisted of the 742-man Minami-Tori-shima Guard Unit, under the command of Rear Admiral Masata Matsubara and the 2,005 man 12th Independent Mixed Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army, under the command of Colonel Yoshiichi Sakata.[4] The United States Navy bombed it repeatedly in 1942[5] and in 1943,[6] but never attempted to capture it (the island was featured in the U.S. film The Fighting Lady). The island was taken by American forces on May 12, 1945. Though isolated, the Japanese were able to resupply the garrison by submarine, using a channel cut through the reef on the northwest side of the island. That channel is still visible today.

The Treaty of San Francisco transferred the island to American control.[7]

The island was returned to Japanese control in 1968, but the Americans retained control of the airstrip and LORAN station.

In 1964, after some delays caused by storms that ravaged the island during construction, the U.S. Coast Guard opened a LORAN-C navigation station on Marcus Island, whose mast was until 1985 one of the tallest structures in the Pacific area. Before replacing Loran A for general marine navigation, Loran C was used by submarine launched Polaris missile systems and the existence and location of Loran C stations was classified. LORANSTA Marcus Island was billeted for 23 U.S. Coast Guard personnel. The commissioning commanding officer was Lieutenant General L. C. Snell. A detachment of SEABEES remained on the island for several months making repairs to the island's air strip.

The island is extremely isolated and Coast Guardsmen stationed on the island served one-year tours that were later modified to allow an R&R visit to mainland Japan at the six-month point. At the end of this isolated tour of duty crew members received an additional 30 days of compensatory leave. While under U.S. administration, on Thursdays a C-130 Hercules from the 345th Tactical Airlift Squadron, Yokota Air Base, Japan, would resupply the island on weekly missions. Often Coast Guardsmen would judge landings by raising placards with large numbers. An unusually long four-hour ground time was scheduled to allow technicians who flew in to perform maintenance on the transmitter and to offload extra fuel from the C-130 to power the island's generator. It also allowed the Coasties to read and answer letters while aircrews would snorkel and collect green glass fishing buoys that wash up on the shore. It takes about 45 minutes to walk around the island.

The station was transferred from the U.S. Coast Guard to the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) on September 30, 1993, and was closed on December 1, 2009.

The island is currently used for weather observation and has a radio station, but little else. Because of its isolation, it is of some interest to amateur radio hobbyists. The JMSDF garrison was supplied by C-130 from Iruma Air Base, or by YS-11 from Haneda or Atsugi Air Base with flights via Iwo Jima on a weekly basis. The runway of Minami Torishima Airport is only 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) long and cannot handle larger aircraft. The island is considered as a separate country for amateur radio awards. The island is off-limits to civilians, except from the Japan Meteorological Agency.

Minami-Tori-Shima area rare earths deposits

- In 2012, Japanese scientists discovered about 6.8 million tons of rare earth elements ("REEs") near the island, enough to supply Japan's current consumption for over 200 years. At that time, around 90% of the world's production of REE came from China, and Japan imported 60% of that.[8]

- In 2013, the location of deposits was confirmed to be approximately 250 kilometres (160 mi) south of the island itself, in the sea-bottom sediments under 5,600 to 5,800 metres (18,400 to 19,000 ft) of water. The rare-earth elements' unusually high concentration of 0.66% was also confirmed.[9]

- In 2014, the Japanese government has assigned a task of developing a necessary rare earths mining technology to a company Mitsui Mining & Smelting Co., Ltd.[10]

Climate

Minami-Tori-shima has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw), with warm to hot temperatures throughout the year. The wettest months are July and August, while the driest months are February and March.

| Climate data for Minamitorishima (1981 - 2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.9 (84) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

33.9 (93) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.7 (76.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.2 (81) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.3 (72.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.8 (82) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.8 (82) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.2 (72) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.1 (79) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.0 (68) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 71.7 (2.823) |

43.2 (1.701) |

42.6 (1.677) |

72.4 (2.85) |

90.3 (3.555) |

61.4 (2.417) |

153.2 (6.031) |

167.3 (6.587) |

99.7 (3.925) |

80.3 (3.161) |

70.3 (2.768) |

97.2 (3.827) |

1,053.6 (41.48) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 11.3 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 8.3 | 13.8 | 16.6 | 14.2 | 11.7 | 9.4 | 12.2 | 130.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 69 | 74 | 79 | 78 | 76 | 77 | 79 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 74 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 166.1 | 178.5 | 227.7 | 237.6 | 274.0 | 299.4 | 274.1 | 252.0 | 256.8 | 250.6 | 213.8 | 175.5 | 2,805.3 |

| Source #1: Japan Meteorological Agency climate normals | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Japan meteorological Agency climate extremes | |||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ http://www.climate-charts.com/Countries/Japan.html

- ↑ Welsch, Bernhard (2001). "The Asserted Discovery of Marcus Island in 1694". Journal of Pacific History. 36 (1): 105–115. doi:10.1080/00223340120049479.

- ↑ Kuroda 1954, 87.

- ↑ Takizawa, Akira; Alsleben, Allan (1999–2000). "Japanese garrisons on the by-passed Pacific Islands 1944-1945". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941-1942.

- ↑ The Raids on Wake and Marcus Islands, Early Raids in the Pacific Ocean. USN Combat Narrative series. Office of Naval Intelligence, United States Navy, 1943.

- ↑ Paramount Battles Involving Essex Class Carriers

- ↑ Article 3 of Treaty of San Francisco: "Japan will concur in any proposal of the United States to the United Nations to place under its trusteeship system, with the United States as the sole administering authority, Nansei Shoto south of 29° north latitude (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands), Nanpo Shoto south of Sofu Gan (including the Bonin Islands, Rosario Island and the Volcano Islands) and Parece Vela and Marcus Island. Pending the making of such a proposal and affirmative action thereon, the United States will have the right to exercise all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction over the territory and inhabitants of these islands, including their territorial waters."

- ↑ Westlake, Adam. "Scientists in Japan discover rare earths in Pacific Ocean east of Tokyo" Japan Daily Press, 29 June 2012. Retrieved: 29 June 2012.

- ↑ University of Tokyo research report "Discovery of rare earths around Minami-Torishima", 5 May 2013. Retrieved: 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Nikkei: Asian review "Seabed offers brighter hope in rare-earth hunt", 25 November 2014. Retrieved: 12 February 2015.

References

- Bryan, William A.: A monograph of Marcus Island; in: Occasional Papers of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Vol. 2, No. 1; 1903

- Kuroda, Nagahisa: Report on a trip to Marcus Island, with notes on the birds; in: Pacific Science, Vol. 8, No. 1; 1954

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941-1942".

- Lévesque, Rodrigue (1997). "The Odyssey of Captain Arriola and His Discovery of Marcus Island in 1694". Journal of Pacific History. 32 (2): 229–233. doi:10.1080/00223349708572841.

- PUB 158 JAPAN Volume 1, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Bethesda, Maryland

- Sakagami, Shoichi F.: An ecological perspective of Marcus Island, with special reference to land animals; in: Pacific Science, Vol. 15, No. 1; 1961

- Welsch, Bernhard (2001). "The Asserted Discovery of Marcus Island in 1694". Journal of Pacific History. 36 (1): 105–115. doi:10.1080/00223340120049479.

- Welsch, Bernhard (2004). "Was Marcus Island Discovered by Bernardo de la Torre in 1543?". Journal of Pacific History. 39 (1): 109–122. doi:10.1080/00223340410001684886.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minami Torishima. |

- Minami Torishima info and pictures

- Marcus Island sunrise, sunset, tides

- Map and aerial photo of Minami Torishima, from the Geographical Survey Institute of Japan website

- The island during the Pacific War (USS Shubrick DD 639)