Mishing people

The Mishing people or Misíng (Assamese: মিছিং) also called Miri (মিৰি), are an ethnic tribal group inhabiting the districts of Dhemaji, Lakhimpur, Sonitpur, Tinsukia, Dibrugarh, Sibsagar, Jorhat and Golaghat of the Assam state in India. The total population is more than 1 million in Assam but there are also more than 50,000 Mishing, divided among three districts: East Siang district, Lower Dibang Valley, and Lohit districts of Arunachal Pradesh. Few of them have settled themselves permanently in National capital Delhi and few hundreds in Mumbai which is the financial capital of India. They are the second largest tribal group in North-East India,[1] first being the Bodos in Assam. They were earlier called Miris in historical days. and the Constitution of India still refers to them as Miris.

Mishing derives from the two word Mi and Toshing/Anshing. "Mi" means man while Anshing/Toshing means worthiness or cool. So Mishing means man of worthiness. The word mi is familiar to many tribe in south east Asia. Mizo and Mishmi are one such example. To depict non-tribal outsiders (most probably the general assamese people) the word Mipak is used extensively which means man of unworthiness. So Mipak is the opposite meaning of Mishing.

Overview

They belong to greater Tani people community which comprises many tribes in Arunachal Pradesh in India and Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) in China. All Tani tribes share linguistic, cultural and ritual similarities.

By virtue of Tibeto-Burman linguistic symmetry, the mishings have also shared ethnologically the Chinese root and the soil. They were believed to be original inhabitant of the northern part of Shansi river stretching Mongolian steppe and said to be remained there during Shang dynasty(1766 to 1122 B.C) up to Chou rule(1122 to 225 B.C) within the pockets of primitive communities which were collectively known as Miao.

There is no written history of Mishings about their migration from hills to the plains of Assam. Though they belong to Tani group of tribes and they used to be hill dwellers, they started living on the banks of rivers in the plains of Assam. The reason for this change of habitat is not known, but there are theories. One theory says that Mishings presently living in plains of Assam were not a one single tribe, but evolved into one when many tribes from various Tani tribes in Arunachal Pradesh migrated to the plains of Assam in search of fertile land as well as in search of civilization progress. Over a period of time, they became known as Miris which means priest in Mishings language. This explains the presence of many Mishings clans with different Mishings dialects as well as different levels of development.

Mishings Autonomy Movement

The Mishings tribe is currently enjoying a sub state like autonomy under the name of Mishing Autonomous Council, which was formed after the signing of MAC act 1995 between Mishings organization and Govt of Assam. MAC includes 40 constituencies in eight upper Assam districts comprising core areas and satellite areas. Executive councillor (EC) from 36 constituency are elected democratically while 4 other members are represented by the ruling government of Assam. Tensions exist between Mishings tribe and other communities regarding inclusion of Non-Mishing villages in MAC areas which led to the formation of O-Mishings organization (Non-Mishings). MAC areas constitute of more than 60% tribal population and other communities are a minority while Mishings are the single largest tribe in the entire area population wise.

Since 1983 Mishing organizations have been demanding Sixth Schedule status under the Constitution of India in Mishing dominated areas.

Miriland/Taniland Demand

In 2009 an armed Mishing organization under the banner of LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC COUNCIL OF MISHING LAND (LDCML) was formed for a separate homeland for the Mishings. Now every Mishings youths have the sentiment for their own homeland while the older generation don't seem to be much interested while keeping their demand only for sixth schedule. There is a wave of awareness and nationalistic pride among the younger guns of the tribes with a serious mindset forming various pages groups in social networking sites. Interesting point is that what compelled Mishings tribe to seek secession from Assamese society the reason may be years of discrimination against tribal's by Assam government and so called high class elite Assamese society. Political and social awareness among Mishings, Carving for own separate Identity also love for own culture and language which is going through continuous threat due to assimilation with Assamese society may be the most rightful reasons.

The Mishings of Arunachal Pradesh

The Mishing of Arunachal Pradesh were the warrior that fought many battle in Arunachal Pradesh. There was constant battle fought among various Tani group for land and property. Some of Mishing people descended down to plains in Assam in order to make a peaceful settlement. Moreover, the river Brahmaputra being a source of various flora and fauna attracted them, for their livelihood. But Mishing of Arunachal Pradesh could resist all the attacks and could Maintain their territory. This Mishing's of Arunachal Pradesh, Who could Protect their land against other Tani group's are Known as Dagdung meaning "Standing Powerful in their land". Many Mishing Personalities of Arunachal pradesh like Late Oiram Bori and Lahore singh Pao started a cultural revolution. Congress Pegu of oyan village was also the main contributor in developing Mishing Culture. Ali-Aye-Leegang was first celebrated in oyan village of Arunachal Pradesh. The 'Lo-ley' was composed by Late Oiram Bori. The Mishing Dress code was designed By Late Lahor Singh Pao of Oyan Village.

Population

According to Census of India conducted in 2001, the population of Mishing in Assam is counted to 5,87,310; of which 2,99,790 Male and 2,87,520 female. Recent survey done by a national is Mishing Organization shows the Mishing population as more than 1 million approx. 12,50,000.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 9,20,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 8,70,000 | |

| 50,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Mishing language | |

The Mishing population residing in Arunachal Pradesh is estimated to be more than 50,000. Literacy rates of Mishing tribe is quite high. It is more than 78% among males and 59% among women averaging to be 68.8%, which is higher than that of Assam as well as India.

Mishing constitute sizeable number of officers of Assam government with ratio much higher than their population. There are now many Mishing successful businessmen among Mishings. Traditionally, Mishing businessmen were into construction line by Assam Government departments like PWD, Irrigation, E&D, NEC(North Eastern Council) etc. But recently, there are many Mishing businessman who are into auto mobiles, IT industry too.

Mishings have the highest number of doctors in Assam compared to the other tribes in Assam.

Tribal Culture and tradition

Folk culture

Mishings have their own unique folk music, dances and musical instruments. Most of these are used or performed on their social and religious festivals.

Folk music

Ahbang It is a verse of hymn of praise and worship of gods and goddesses. Ahbang is sung by the Mibu (priest) at rituals. There is also community Ahbangs generally used in Pobua, a ritual festival, praying for better crops, health and happiness.

Kaban It is one of the oldest forms of Mishing folk songs. It is lamentation music and recalls sad events. At the death of a dear one, the women burst out into a sort of cry and song which for an outsider may sound funny.

Tebo Tekang It is a romantic lyric, narrating some love encounters.

Siuhlung Nitom It is a melancholic song, sung in lonely places like jungle.

Bini These are lullabies sung either at home or in the field, taking babies to places of work. The baby is tied to the back of the mother or the young babysitter.

Midang Nitom This is usually sung at the time of ushering in a bride to her new home, often in order to tease her. These too are rather melancholic, since they depict the sadness of brides wailing at being separated from her family, friends and the familiar childhood environment.

Oi Nitom It is the most popular form of Mishing folk song, sung by Mishing youths when they are working or moving about the fields, woods, etc. It is an integral part of the Mishing Sohman (dance). It has a variety of themes ranging from romance, humour, tragedy, and socio-cultural motifs. Each line in an Oi-Nitom is of seven syllables.

Musical instruments

Mishings have rich folk music. Apart from dumdum, lupi, lehnong, marbang, bali, etc. used in Gumrak dance and which are common to other locals, the following are the typical type of traditional instruments played in Mishing folk music: ezuk tapung, derki tapung, tumbo, tapung tutok tapung, ketpong tapung, gekre tapung, dendun, dumpak koreg, gunggang, tulung etc. These are mostly wind instruments made of bamboo. Yoksa (sword) is used as a musical instrument by the priest during religious dance.

Dances

There are many types of Mishing dances, and each has their particular rules. Gumrag is performed five times in circles. Drums and cymbols are the usual musical instruments for the dances.

Mibu Dagnam It is a priestly dance performed mostly during Porag, the harvesting festival, observed in the Murong, the community hall of the Mishings. The priest sings the Ahbang while performing this ritual dance.

Selloi This is a kind of merry-making song and dance often performed for fun, by young boys and girls with the accompaniment of drums or cymbols. It marks the beginning of influx of the Mishing people from hills to plains of Assam.

Lereli Occasionally, all sections of Mising people indulge in singing and dancing lereli in sheer fun and merriment, especially at meeting old friends.

Ejug Tapung Sohman This is a very ancient form of dance performed to the accompaniment of ejug tapung, a wind instrument resembling the snake charmer’s been.

Gumrak Sohman This dance is performed on the occasion of Ali-Aye-Ligang.

Lotta Sohman This dance is performed on any occasion, as an expression of joy or community celebration. Old and young, all join in these dances

Social structure

The Mishings believe Abotani as their ancestor is supposed to be a son of mother Sun and father Moon of the Heavenly abode. The Mishing people inhabiting by the Plains believe Guhmeen as one of the earliest ancestors, the forefather of a lineal family of Abotani. The sons of Guhmeen are grouped in clans (opeen), the names of which are represented by the existing surnames in the society. They are all blood related brothers with a social restriction of matrimonial relationship among them.

In some localities, a few non-Mishing speaking groups like Bihiya, Samurguria etc. are predominant. These groups write some of their surnames as Saikia, Baruah, Medhi, Kachari, Patgiri Changmai etc. and soon forget their Guhmeen and Opeen Identity. Moreover, the usage of the term Moyengia, Oyengia and Sayengia etc. carry no meaning in determining an opeen because families of different Opeen are found in the said group. In the same way, the division into Borgam and Dohgam, which was an administrative system introduced during Ahom Kingdom, is non-existent in the society today. As such the multifarious form of division, have no bearing at all in identification of Guhmeen ad Opeen Concept since time immemorial in maintaining their fabric of socio-cultural system.

The Opeen (Clans) of Guhmeen are all blood related brothers known as Urom bibosunam Beerrang originating from a common ancestor father and there is no restriction in offering prayers in the Rituals in common platform generations together. There is another form of brotherhood existing in the society which has been traditionally accepted as affiliated brother or Tomin sunam Beerrang from different opeen. In both types of Brotherhood marriage among themselves is forbidden in the society.

The community has various Clans as, including: Bori, Gam, Doley, Dao, Darig, Dang, Jimey, Kuli, Kutum, Kumbang, Kaman, Kardong, Kari, Lagachu, Loying, Modi, Moyong, Morang, Mili, Medok, Misong, Narah, Ngate, Pangging, Pégu, Pérme, Pértin, Pait, Pagag, Patir, Patiri, Padi, Payeng, Payun, Pao, Pádun, Regon, Rátan, chungkrang, Chintey, Charoh, Taw, Taye, Taid, Tayung, and Yein.

There are further classification as Delu, Dagdung, Dagtok, Mohying, Padam, Pagro, Oyan.

The Opeen Urom Bibosunam Beerrang are related respectively as brothers with the Tomsunam Beerrang. For example: The Opeen mentioned above *1. Kuli, Kutum, Kumbang, Koman of Opin Urom Bibosunam Bírrang have affiliated brotherhood with ⇔ *1.Doley, Padi, Ratan, Regon, Like wise for the other in the listing.

GUHMEEN-------------&------------ OPEEN(clan) _________________________________

Caydo/Caye ------------------- Tayung,Tayeng,Dang

Cantu --------------------- Medok,Mego

Sohbo - ------------------- Doley,Misong,Darig,Kagyung

Longging --------------- Panging,Narah,chinte,Pagag,Padun,Pahmey,Lagasu Pahnyang

Johtir --------------------- Pateer

Johbo --------------------- Taku

Tohri --------------------- Bori

Sohdo --------------------- Pait

Pedong --------------------- Chungkrang,Jimey,Yirang

Baki ---------------------- Kumbang,Regon

Boju --------------------- Pahdi,Bahshing

Bojum -------------------- Tarag

Bomi -------------------- Kardong,Kutum,Kuli,Mili

Bonung ------------------- Daw,Morang,Mipun

Minyong Pankong----------- Pahyeng,Ngatey

Lohring ------------------ Mohdi

Lohdy ----------------- Tawid

Lohying ---------------- Charoh,Paw,Perme,Pertin

Lingkong ---------------- Taye, Yewin

Lingkung/loying ------------- Yewin

Yohbo -------------- Taw

Kondar ----------------Pegu,Kari,Gudang,Gupit,Chandi,Pathori,Patgiri

relates with

↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓↓

Tomeen sunam beerrang(Affiliated brotherhood)

- 1. Doley, Padi, Ratan, Regon, Dao.

- 2. Lagasung, Pateer, Paid, Medok, Taid Sungkrang, Kardong, Jimey.

- 3. Kuli, Kutum, Kumbang, Mili, Yewn, Misong, Taye, Dao, Ratan.

- 4. Pao, Loying, Pawe, Tayeng

- 5. Taye, yein, Doley

- 6. Pateer, Pegu, Tayung, Lagasung.

- 7. Darig, CHungkrang, Pateer, Mohdi, Mohyong

- 8. Permey, Doley,

- 9. Morang, Pangging, Dang

- 10. Kuli, Doley, Kutum, Kumbang

- 11. Charoh, Pangging, Pertin, Pogag

- 12. Doley, Tawíd, Tayung

- 13. Pangging, Permey, Pahid, Pertin

- 14. Yewin, Taye, Kuli, Kutum, Kumbang, Koman

- 15. Doley, Kuli, Kutum, Kumbang

- 16. Tao

- 17. Gam, Payeng, Medok, Kardong

- 18. Pegu

- 19. Panyang

It is believed that this practice among the Mishing people have been the backbone of maintaining genetic purity among the Clan members, also it has helped them from inbreeding disorders in their kin. It has also provided a bond of brotherhood among Mishing community. The community has no sign of any genetical disorder among its people.

Marriages

The Mishings are a patrilineal and patrilocal society and so, as per customary law, only the male children are entitled to inherit the property of a family. However, daughters can inherit the clothes and jewellery of their mothers.

Marriages amongst the Mishings take place in four ways: (i) formal marriages through negotiation, (ii) marriage by elopement, (iii) marriage through a very simple ceremony, and (iv) marriage by force. The last one, in which a man makes a woman his wife against her will by whisking her away from some place and starting to live together, is no longer in practice. Extreme poverty or inconvenience force families to arrange a marriage of the third kind, in which a few elders, invited to the house of the groom, bless the would-be couple over a few bowls of rice beer – and the wedding is over. The most common form of marriage in rural areas even today is the one by elopement. When a boy is in love with a girl and intends to marry her, but cannot afford the cost of a formal marriage, or expects some opposition to the marriage from some quarter, or would like to start a conjugal life without delay, he chooses elopement with the girl as the best option. More often than not, marriages by elopement are followed by due social recognition through simple formalities. Formal marriages are arranged through two or three stages of negotiation, but although arranged by parents or guardians, the marriage of a boy and a girl totally unknown to each other, would be very rare. Formal marriages amongst them appear to have been influenced to a great extent by the practice of such marriages amongst their neighbours in the valley. It is now common for the educated and the well-to-do parents to perform the marriages of their children in the formal way. Polygamy is permissible as per customary law, but it is not looked upon as an act of honour anymore. Polyandry is unknown altogether. Widows or widowers can remarry. Customary law allows divorces, but they are not very common. It is also customary for a groom’s parents or guardians to pay bride price – mostly nominal – to the parents or guardians of the bride. Clan endogamy is taboo.

Dwelling, Village Chief, Council

A traditional Mishing house is stilted. It has a thatched top and is patterned simply like the letter ‘ I ’. It is built usually with wooden posts, beams, truss and supporting forks, but bamboo is used extensively for flooring and roofing. The more the number of nuclear families living in the same house, the longer the ‘ I ’ would be. The granary is built a little close to the house and a cowshed too would not be far away. Mishing villages are generally large in size, consisting of around fifty-to-sixty households on an average.

The traditional chief of a Mishing village was called a Ga:m. He presided at the sittings of the village Kebang (the village council), which deliberated upon different matters concerning the wellbeing of the village community as well as complaints of individual members or groups in the community. The Kebang was the legal, judicial and executive authority of the community, although the final say on all matters, barring the ones relating to their faith, was that of the Ga:m. Cases of social and criminal offences were heard by the Kebang, and persons found guilty were penalized. The Ga:m has been replaced with Gambura (gaonburha in mipak language) a petty village level agent of the government, since the days of the British. Kebang now denotes an association. Various mising nationalistic organization have been formed during the modern era of civilization like Takam Mishing Porin Kebang ( Mishing Student Union) and Mishing Bane Kebang ( Mishing Legislative Council) for the protection of the tribe from any harmful conspiracy by the non mishings or popularly known as MIPAKS

Culture and festivals

Mishing people celebrate various festivals, though, the two chief traditional festivals of the Mishings are the Ali-Aye-Leegang and the Pohrag, both connected with their agricultural cycle.

Ali Aye Leegang

Ali means roots and shoots, Aye means Fruit and Leegang means beginning. Thus the words means the beginning of sowing of seeds. Ali-Aye-Leegang, is celebrated in the first Wednesday of fagun month (Assamese Calendar), this date falls in the February month of the English calendar. The festival marks the beginning of the sowing season. The people of this community are mainly agrarian, so the festival of Ali Aye Leegang marks the beginning of a new agricultural calendar for them. Ali-aye Leegang is a five-day festival. The celebrations start on a Wednesday, which is considered an auspicious day by the Mishings, with the heads of families sowing ceremonially rice paddy seeds in a corner of their respective rice fields in the morning hours and praying for a good crop during the year as well as for general plenty and wellbeing. Young men and women celebrate the occasion by singing and dancing at night in the courtyard of every household in the village to the accompaniment of drums, cymbals and a gong. The gong is not used on any festive occasion other than the Ali-Aye Leegang. Similarly, the drums have specific beats for this festival. The troupe accepts from each household offers of rice beer, fowls, and/or cash. After the singing and dancing in this way is over, the youths hold a feast on the third day. The fourth is a day of taboos: activities like cutting trees, using agricultural implements in any way, using fire in agricultural fields, eating eggs, fruit (especially sour ones), frying items of food etc. must not be done on this day. The taboos are over on the fifth day, and the festival concludes with eating and drinking in the evening. A kind of sticky rice, packed in leaves of wild cardamom and boiled, is a special item of food on such festive occasions.

Po:rag is the post-harvest festival of the Mishings. Harvesting of paddy rice in autumn is very common now amongst the Mishings and so a Po:rag is usually observed now sometime in early winter or early spring. But there was a time when a harvest in summer too was very common amongst them and so Po:rag was celebrated earlier in the months of August or September also. It is a very expensive three-day festival (reduced to two days or even one these days, depending on the extent of preparation on the part of the organizers in terms of items of food and drinks) and so held once in two-to-three years or so. Entertainment during the celebrations is open to everyone, young and old, of the village, and invitations are also extended formally to many guests, including some people of neighbouring villages, to join the celebrations. More significantly, it is customary on this occasion to invite the women who hail from the village but have been married to men of other villages and places, far and near. This makes Po:rag a grand festival of reunion. Moreover, apart from the husbands of the women so invited, a group of young men and women, who can sing and dance, is expected to accompany each of them. No formal singing, dancing and drumming contests are organized, but the congregation of many singers, dancers and drummers from different villages, in addition to the ones in the village, turns the festival into some kind of a friendly music and dance tournament, as it were. This has an amplifying effect on the air of joy that the festival exudes. The sole responsibility for organizing the festival is vested in a body of young men and women, called Meembiur-yahmey (literally, ‘young women-young men’). The organization is run with a good degree of discipline, following the provisions of an unwritten but well-respected code of conduct. Erring individuals are given hearings and penalized, if found guilty.

Another occasion called Dobur is an animistic rite performed occasionally by the village community by sacrificing a sow and some hens for different purposes, such as to avert a likely crop failure and ensure general well being of the community, or to avert the evil effects of a wrongdoing on the part of a member of the community, etc. The form of observance of Dobur varies according to the purpose. In the most common form, the younger male members of a village beat the walls of every house in the village from one end to the other with big sticks to drive away the ghosts and goblins hiding in nook and corner and perform the sacrificial rite at some distance away from the village, and hold a feast there. Anyone passing unwittingly through the venue of the rite has to stop in the place till evening or pay a fine.

Some of the features of Assamese Bihu dances in recent times, boys and girls dancing together, for instance, may have been borrowed from the Mishings.

Economy

Agriculture is the lifeblood of the economy of the Mishings. They grow different varieties of rice paddy, some of which they sow in spring for harvesting in summer, some others being transplanted during the rainy season and harvested in autumn. They also grow mustard, pulses, maize, vegetables, tobacco, bamboo, areca, etc., chiefly for their own use, with the exception of mustard, which brings them some cash. Generally speaking, they are poor horticulturists. The women contribute to the income of the family by rearing pigs, fowls and, occasionally, goats. They are buyers, not makers, of metallic utensils and jewellery. They are also not known for carpentry. However, they make almost all the tools required for their day-to-day life, such as baskets, carry bags, trays, boxes, fish traps of various kinds, hencoops, etc., using bamboo and cane as material. The wooden items they make include their boat-shaped mortar and the pestle, and, of course, canoes, so indispensable for riparian people living in flood-prone areas. Today a small percentage of their population have different categories of jobs, especially in the public sector, small trading, etc. as sources of income

Religion and rituals

Mishings are one of the most colourful tribal groups. Mishing has its own religion named Mishing faith. Donyi (Sun) is the god of Mishings. Even the Christian missionaries couldn't convert them completely into Christian. People are mostly non religious as they are fun loving and enjoy life at the fullest without caring much about any strict religious injunctions. The traditional religious beliefs and practices amongst the Mishings are animistic.

In the Brahmaputra valley, the Mishings have undergone a process of acculturation. They believe in different supernatural beings haunting the earth, usually unseen. These supernatural beings fall into four categories, viz. uyu or ui (usually malevolent spirits inhabiting the waters, the woods, the skies, etc. capable of causing great harm including physical devastation), urom po-sum (hovering spirits of the dead, who may cause illness or other adverse conditions), guhmeen-sohing (benevolent ancestral spirits), and epom-yapom (spirits inhabiting tall, big trees, who are generally not very harmful, but who may abduct human beings occasionally, cause some physical or mental impairment and release them later). Barring the epom-yapom, all the supernatural beings need to be propitiated with sacrificial offerings (usually domestic fowl), both periodically and on specific occasions of illness, disaster, etc. Even the benevolent guardian spirits are propitiated from time to time for the all-round wellbeing of a household. Nature worship as such is not a common practice amongst Mishings. But the god of thunder is propitiated from time to time, and although not worshipped or propitiated, the Sun (who they call Ane-Donyi ‘Mother Sun’) and the Moon (who they call Abu Polo ‘Father Moon’) are invoked on all auspicious occasions.

The leader of their animistic faith is called a mibu (also called mirí earlier), their priest or medicine man, who is supposed to be born with special powers of communion with supernatural beings. While mibus are on their way out amongst the Mishings owing to the introduction of modern education and healthcare amongst them, propitiation of supernatural beings continue to mark their religious life (see Mibu ahbang below for more on Mibus)

In addition, they have embraced in the valley some kind of a monotheistic Hinduism as passed on to them by one of the sects of the Vaishnavism of Sankardeva (1449-1568 A.D.), the saint-poet of Assam. As faiths, the two forms, animism and Vaishnavism, are poles apart, but they have coexisted in the Mishing society without any conflict whatsoever, primarily because of the fact that the form of Vaishnavism, as they have been practising it, has not interfered with their traditional customs (drinking rice beer and eating pork, or using them on socio-religious occasions, for instance). Their religious life in the valley has thus assumed a fully syncretistic character, as it were, and it has given them a homogenous characters of both animistic donyi poloism and vaishnavism. There are sizeable number of Christians among mishings both Roman Catholic and Baptist. World famous river island Majuli is a home to large number of mishing Christians.

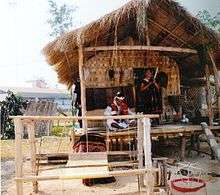

Weaving and textiles

The traditional craft of weaving is a very bright aspect of Mishing culture. It is an exclusive preserve of the Mishing woman, who starts her training in the craft even before she reaches her teens. For the male, she weaves cotton jackets, light cotton towels, endi shawls, thick loin cloths, and, occasionally, even shirtings. For women she weaves a variety of clothes, such as ege "the lower garment of Mishing women", rihbi (a sheet with narrow stripes, wrapped to cover the lower garment and the blouse), gaseng (used for the same purpose as that of a rihbi, but having, unlike a rihbi, broad stripes of contrastive colours), gero (a sheet, usually off-white, wrapped round the waist to cover the lower part of the body, or round the chest to cover the body down to the knees or so), seleng gasor (a light cotton sheet, worn occasionally instead of a rihbi or a gaseng), riya (a long, comparatively narrow, sheet, wrapped, a bit tightly, round the chest), segrek (a loose piece of cloth, wrapped round the waist by married women to cover the eagey down to the knees), a pohtub (a scarf used to protect the head from the sun, dirt, etc.), and nisek (a piece of cloth to carry a baby with). Before yarn, produced by modern textile factories, was available in the market, Mishings used to grow cotton and obtain cotton yarn by spinning. The use of endi yarn, obtained from worms fed on leaves of castor-oil plants, was probably common amongst them. However, they learnt the use of muga (silk obtained from silkworms fed on a kind of tall tree, called som in Assamese) and of paat (silk obtained from silkworms fed mulberry leaves) from their neighbours in the valley. Even now Mishing women weave cloths, using muga and paat silk, very sparingly. Thus weaving cotton clothes is the principal domain of the Mishing weaver. She has good traditional knowledge of natural dyes.

A special mention has to be made here of the Mishing textile piece, called gadu. It is the traditional Mishing blanket, fluffy on one side, and it is woven on a traditional loin loom. The warp consists of cotton spun into thick and strong yarn, and the weft of cotton, turned into soft yarn and cut into small pieces for insertion, piece by piece, to form the fluff. It is obvious that weaving a gadu is a very laborious affair like weaving expensive carpets, requiring the weaver to spend a lot of time on her loin loom, and, as the younger women in a family would, generally, not have enough time for such a work, it is the ageing ones staying at home that do it. There has been a drastic decline of the gadu craft during the years after independence because of the availability of inexpensive blankets in the market.

Language and literature

Mishing Agom Kebang is the Mishing supreme body about Mishing language. It has been working relentlessly towards development of Mishing language. Mishing has been introduced in primary level education in Assam. Mishings have written dictionary as well as well developed grammar. Mishing language belong to Indo-Tibetan group of languages. It has very close similarities with other Tani languages in Arunachal Pradesh.

The First Mishing grammar was written in 1849 by Rev. Robinson in 'Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal' (Vol, 18, part 1, page 224).[3]

After that British Political officer, Joseph Francis Needham, based in Sadiya published another Mishing grammaer 'Outline grammar of the Shaiyang Miri Language as spoken by the Miris of that clan residing the neighbourhood of Sadiya', 1886.

The first Mishing books were published by Reverend James Herbert Lorrain in 1902 with name Isorke Doyinge (Story of God) and Jisuke Doyinge (Story of Jesus) in 1902.

The first Mishing dictionary was published in 1910, from Shillong by Reverend James Herbert Lorrain.

Rev. L.W.B. Jackman published "Keyum kero Kitab (1914)", "Rom Kiding kela Korintian Doying (1916) and "Mathike Annam Baibal" (1917).

The Mishing language was converted to written form with written grammar in 1849. Since 1980, books, magazines, newspapers have been published in Mishing language. For example Mishing Gompir Kumsung, a dictionary of Mishing by Tabu Tawid.

See also

- Mishing Agom Kebang

- Mishing Autonomous Council

- Mishing language

- Mishing Baptist Kebang

- Takam Mishing Porin Kebang

References

- ↑ J. S. Bhandari Kinship, Affinity, and Domestic Group: a study among the Mising 1992 "This is a comprehensive ethnography account of the Mishing, the second largest tribe of Assam, inhabiting the Brahamputra Valley."

- ↑ Census of India - Socio-cultural aspects, Table ST-14 (compact disc), Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, 2001

- ↑ Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 1876 Page 13 "Mr. Brown, and another in the Journal of the Bengal Asiatic Society ; the Abor, of whose language we have a vocabulary prepared by Captain Smith ; the Dofiia, of which we have a grammar by Robinson : the Miri, of whose language we have a grammar prepared by Mr. Robinson (this tribe "

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mishing people. |

- macgov.in Mishing Autonomous Council (MAC)

- MisingOnline.com

- Mishing Agom Kébang

- Societial adaptation to environmental changes: natural resources management and shifting definitions of territory among the Mishing tribe in the Brahmaputra River floodplain (Assam, NE India), by Emilie Cremin, PhD in Geography, University Paris 8 (France).

- http://www.misingregam.asia