Money multiplier

In monetary economics, a money multiplier is one of various closely related ratios of commercial bank money to central bank money under a fractional-reserve banking system.[1] Most often, it measures an estimate of the maximum amount of commercial bank money that can be created, given a certain amount of central bank money. That is, in a fractional-reserve banking system, the total amount of loans that commercial banks are allowed to extend (the commercial bank money that they can legally create) is equal to an amount which is a multiple of the amount of reserves. This multiple is the reciprocal of the reserve ratio, and it is an economic multiplier.[2]

Although the money multiplier concept is a traditional portrayal of fractional reserve banking, it has been criticized as being misleading. The Bank of England and the Standard & Poor's rating agency (amongst others) have published papers whose authors the concept .[3][4] Several countries (such as Canada, the UK, Australia and Sweden) set no legal reserve requirements.[5] Even in those countries that do (such as the USA), the reserve requirement is as a ratio to deposits held, not a ratio to loans that can be extended.[5] Under the Basel III global regulatory standard, it is the level of bank capital that determines the maximum amount that banks can lend.[6] Basel III does stipulate a liquidity requirement to cover 30 days net cash outflow expected under a modeled stressed scenario (note this is not a ratio to loans that can be extended) however liquidity coverage does not need to be held as reserves but rather as any high-quality liquid assets [7][8]

In equations, writing M for commercial bank money (loans), R for reserves (central bank money), and RR for the reserve ratio, the reserve ratio requirement is that the fraction of reserves must be at least the reserve ratio. Taking the reciprocal, which yields meaning that commercial bank money is at most reserves times the latter being the multiplier.

If banks lend out close to the maximum allowed by their reserves, then the inequality becomes an approximate equality, and commercial bank money is central bank money times the multiplier. If banks instead lend less than the maximum, accumulating excess reserves, then commercial bank money will be less than central bank money times the theoretical multiplier.

Definition

The money multiplier is defined in various ways.[1] Most simply, it can be defined either as the statistic of "commercial bank money"/"central bank money", based on the actual observed quantities of various empirical measures of money supply,[9] such as M2 (broad money) over M0 (base money), or it can be the theoretical "maximum commercial bank money/central bank money" ratio, defined as the reciprocal of the reserve ratio, [2] The multiplier in the first (statistic) sense fluctuates continuously based on changes in commercial bank money and central bank money (though it is at most the theoretical multiplier), while the multiplier in the second (legal) sense depends only on the reserve ratio, and thus does not change unless the law changes.

For purposes of monetary policy, what is of most interest is the predicted impact of changes in central bank money on commercial bank money, and in various models of monetary creation, the associated multiple (the ratio of these two changes) is called the money multiplier (associated to that model).[10] For example, if one assumes that people hold a constant fraction of deposits as cash, one may add a "currency drain" variable (currency–deposit ratio), and obtain a multiplier of

These concepts are not generally distinguished by different names; if one wishes to distinguish them, one may gloss them by names such as empirical (or observed) multiplier, legal (or theoretical) multiplier, or model multiplier, but these are not standard usages.[9]

Similarly, one may distinguish the observed reserve–deposit ratio from the legal (minimum) reserve ratio, and the observed currency–deposit ratio from an assumed model one. Note that in this case the reserve–deposit ratio and currency–deposit ratio are outputs of observations, and fluctuate over time. If one then uses these observed ratios as model parameters (inputs) for the predictions of effects of monetary policy and assumes that they remain constant, computing a constant multiplier, the resulting predictions are valid only if these ratios do not in fact change. Sometimes this holds, and sometimes it does not; for example, increases in central bank money may result in increases in commercial bank money – and will, if these ratios (and thus multiplier) stay constant – or may result in increases in excess reserves but little or no change in commercial bank money, in which case the reserve–deposit ratio will grow and the multiplier will fall.[11]

Mechanism

There are two suggested mechanisms for how money creation occurs in a fractional-reserve banking system: either reserves are first injected by the central bank, and then lent on by the commercial banks, or loans are first extended by commercial banks, and then backed by reserves borrowed from the central bank. The "reserves first" model is that taught in mainstream economics textbooks,[1][2] while the "loans first" model is advanced by endogenous money theorists.

Reserves first model

In the "reserves first" model of money creation, a given reserve is lent out by a bank, then deposited at a bank (possibly different), which is then lent out again, the process repeating[2] and the ultimate result being a geometric series.

Formula

The money multiplier, m, is the inverse of the reserve requirement, RR:[2]

This formula stems from the fact that the sum of the "amount loaned out" column above can be expressed mathematically as a geometric series[12] with a common ratio of

To correct for currency drain (a lessening of the impact of monetary policy due to peoples' desire to hold some currency in the form of cash) and for banks' desire to hold reserves in excess of the required amount, the formula:

can be used, where "Currency Drain Ratio" is the ratio of cash to deposits, i.e. C/D, and the Desired Reserve Ratio is the sum of the Required Reserve Ratio and the Excess Reserve Ratio.[10]

The formula above is derived from the following procedure. Let the monetary base be normalized to unity. Define the legal reserve ratio, , the excess reserves ratio, , the currency drain ratio with respect to deposits, ; suppose the demand for funds is unlimited; then the theoretical superior limit for deposits is defined by the following series:

.

Analogously, the theoretical superior limit for the money held by public is defined by the following series:

and the theoretical superior limit for the total loans lent in the market is defined by the following series:

By summing up the two quantities, the theoretical money multiplier is defined as

where and

The process described above by the geometric series can be represented in the following table, where

- loans at stage are a function of the deposits at the precedent stage:

- publicly held money at stage is a function of the deposits at the precedent stage:

- deposits at stage are the difference between additional loans and publicly held money relative to the same stage:

| Deposits | Loans | Publicly Held Money | |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | ||

| … | … | … | … |

| … | … | … | … |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Total Deposits: | Total Loans: | Total Publicly Held Money: |

| |

|||

Table

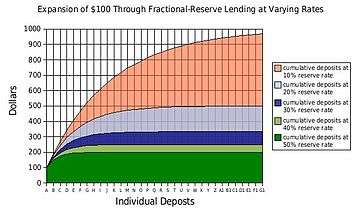

This re-lending process (with no currency drain) can be depicted as follows, assuming a 20% reserve ratio and a $100 initial deposit:

| Individual Bank | Amount Deposited | Lent Out | Reserves |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 100.00 | 80.00 | 20.00 |

| B | 80.00 | 64.00 | 16.00 |

| C | 64.00 | 51.20 | 12.80 |

| D | 51.20 | 40.96 | 10.24 |

| E | 40.96 | 32.77 | 8.19 |

| F | 32.77 | 26.21 | 6.55 |

| G | 26.21 | 20.97 | 5.24 |

| H | 20.97 | 16.78 | 4.19 |

| I | 16.78 | 13.42 | 3.36 |

| J | 13.42 | 10.74 | 2.68 |

| K | 10.74 | |

|

| |

|

|

Total Reserves: |

| |

|

|

89.26 |

| |

Total Amount of Deposits: | Total Amount Lent Out: | Total Reserves + Last Amount Deposited: |

| |

457.05 | 357.05 | 100.00 |

Example

For example, with the reserve ratio of 20 percent, this reserve ratio, RR, can also be expressed as a fraction:

So then the money multiplier, m, will be calculated as:

This number is multiplied by the initial deposit to show the maximum amount of money it can be expanded to.[17]

Another way to look at the monetary multiplier is derived from the concept of money supply and money base. It is the number of dollars of money supply that can be created for every dollar of monetary base. Money supply, denoted by M, is the stock of money held by public. It is measured by the amount of currency and deposits. Money Base, denoted by B, is the summation of currency and reserves. Currency and Reserves are monetary policy that can be affected by the Federal Reserve. For example, the Federal Reserve can increase currency by printing more money and they can similarly increase reserve by requiring a higher percentage of deposits to be stored in the Federal Reserve.

Mathematically: Let and where

M=Money Supply

C=Currency

D=Deposits

B=Money Base

R=Reserve

By algebraic manipulation

is the multiplier. Therefore, if money base is held constant, the ratio of D/R and D/C affects the money supply. When the ratio of deposits to reserves (D/R) reduces, the multiplier reduces. Similarly, if the ratio of deposits to currency (D/C) falls, the multiplier falls as well. [nb 1]

The multiplier effect is relevant to considering monetary and fiscal policies, as well how the banking system works. For example, the deposit, the monetary amount a customer deposits at a bank, is used by the bank to loan out to others, thereby generating the money supply. Most banks are FDIC insured (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation), so that customers are assured that their savings, up to a certain amount, is insured by the federal government. Banks are required to reserve a certain ratio of the customer's deposits in reserve, either in the form of vault cash or of a deposit maintained by a Federal Reserve Bank. . Therefore, if the Federal Reserve Bank (and hence its monetary policy) requires a higher percentage of reserve, then it lowers the bank's financial ability to loan.

Loans first model

In the alternative model of money creation, loans are first extended by commercial banks – say, $1,000 of loans (following the example above), which may then require that the bank borrow $100 of reserves either from depositors (or other private sources of financing), or from the central bank. This view is advanced in endogenous money theories, such as the Post-Keynesian school of monetary circuit theory, as advanced by such economists as Basil Moore and Steve Keen.[18]

Finn E. Kydland and Edward C. Prescott argue that there is no evidence that either the monetary base or Ml leads the cycle.[19]

Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof of the IMF Research Department, argue that: the “deposit multiplier“ of the undergraduate economics textbook, where monetary aggregates are created at the initiative of the central bank, through an initial injection of high-powered money into the banking system that gets multiplied through bank lending, turns the actual operation of the monetary transmission mechanism on its head. At all times, when banks ask for reserves, the central bank obliges. According to this model, reserves therefore impose no constraint and the deposit multiplier is therefore a myth. The authors therefore argue that private banks are almost fully in control of the money creation process.[20]

Implications for monetary policy

The multiplier plays a key role in monetary policy, and the distinction between the multiplier being the maximum amount of commercial bank money created by a given unit of central bank money and approximately equal to the amount created has important implications in monetary policy.

If banks maintain low levels of excess reserves, as they did in the US from 1959 to August 2008, then central banks can finely control broad (commercial bank) money supply by controlling central bank money creation, as the multiplier gives a direct and fixed connection between these.

If, on the other hand, banks accumulate excess reserves, as occurs in some financial crises such as the Great Depression and the Financial crisis of 2007–2010, then this relationship breaks down and central banks can force the broad money supply to shrink, but not force it to grow:

By increasing the volume of their government securities and loans and by lowering Member Bank legal reserve requirements, the Reserve Banks can encourage an increase in the supply of money and bank deposits. They can encourage but, without taking drastic action, they cannot compel. For in the middle of a deep depression just when we want Reserve policy to be most effective, the Member Banks are likely to be timid about buying new investments or making loans. If the Reserve authorities buy government bonds in the open market and thereby swell bank reserves, the banks will not put these funds to work but will simply hold reserves. Result: no 5 for 1, “no nothing,” simply a substitution on the bank’s balance sheet of idle cash for old government bonds.— (Samuelson 1948, pp. 353–354)

Restated, increases in central bank money may not result in commercial bank money because the money is not required to be lent out – it may instead result in a growth of unlent reserves (excess reserves). This situation is referred to as "pushing on a string": withdrawal of central bank money compels commercial banks to curtail lending (one can pull money via this mechanism), but input of central bank money does not compel commercial banks to lend (one cannot push via this mechanism).

This described growth in excess reserves has indeed occurred in the Financial crisis of 2007–2010, US bank excess reserves growing over 500-fold, from under $2 billion in August 2008 to over $1,000 billion in November 2009.[21][22]

References

- 1 2 3 (Krugman & Wells 2009, Chapter 14: Money, Banking, and the Federal Reserve System: Reserves, Bank Deposits, and the Money Multiplier, pp. 393–396)

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Mankiw 2008, Part VI: Money and Prices in the Long Run: The Money Multiplier, pp. 347–349)

- ↑ http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

- ↑ http://ommekeer-nederland.nl/documents/standard-poors-rating-services-lending-creating-deposits.pdf

- 1 2 http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp1136.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs238.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bis.org/bcbs/basel3/b3summarytable.pdf

- 1 2 (Krugman & Wells 2009, p. 395) calls the observed multiplier the "actual money multiplier".

- 1 2 (Mankiw 2002, Chapter 18: Money Supply and Money Demand: A Model of the Money Supply, pp. 486–487)

- ↑ (Mankiw 2002, p. 489)

- ↑ http://www.mhhe.com/economics/mcconnell15e/graphics/mcconnell15eco/common/dothemath/moneymultiplier.html

- ↑ Table created with the OpenOffice.org Calc spreadsheet program using data and information from the references listed.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Education - How does the Fed Create Money? http://www.federalreserveeducation.org/fed101_html/policy/money_print.htm

- See the link to "The Principle of Multiple Deposit Creation" pdf document towards bottom of page.

- ↑ An explanation of how it works from the New York Regional Reserve Bank of the US Federal Reserve system. Scroll down to the "Reserve Requirements and Money Creation" section. Here is what it says:

- "Reserve requirements affect the potential of the banking system to create transaction deposits. If the reserve requirement is 10%, for example, a bank that receives a $100 deposit may lend out $90 of that deposit. If the borrower then writes a check to someone who deposits the $90, the bank receiving that deposit can lend out $81. As the process continues, the banking system can expand the initial deposit of $100 into a maximum of $1,000 of money ($100+$90+81+$72.90+...=$1,000). In contrast, with a 20% reserve requirement, the banking system would be able to expand the initial $100 deposit into a maximum of $500 ($100+$80+$64+$51.20+...=$500). Thus, higher reserve requirements should result in reduced money creation and, in turn, in reduced economic activity."

- ↑ Bank for International Settlements - The Role of Central Bank Money in Payment Systems. See page 9, titled, "The coexistence of central and commercial bank monies: multiple issuers, one currency": http://www.bis.org/publ/cpss55.pdf

A quick quote in reference to the 2 different types of money is listed on page 3. It is the first sentence of the document:

- "Contemporary monetary systems are based on the mutually reinforcing roles of central bank money and commercial bank monies."

- ↑ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2001), Principles of Macroeconomics

- ↑ Debtwatch No. 38: The GFC—Pothole or Mountain?, August 30, 2009

- ↑ https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/qr/qr1421.pdf

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

- ↑ EXCRESNS series, St. Louis Fed

- ↑ Followup on Samuelson and monetary policy, Paul Krugman, New York Times, December 14, 2009

- Kydland, Finn E.; Prescott, Edward C., "Business Cycles: Real Facts and a Monetary Myth", Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 14 (2): 3–18

- Krugman, Paul; Wells, Robin (2009), ISBN 978-0-7167-7161-6; a mainstream introductory text in macroeconomics. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Mankiw, N. Gregory (2008), Principles of Macroeconomics (5th ed.), ISBN 978-0-324-58999-3; a mainstream general introductory text to economics.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory (2002), Macroeconomics (5th ed.), ISBN 978-0-7167-5237-0; a mainstream intermediate text in macroeconomics.

- Samuelson, Paul (1948), Economics

Notes

- ↑ This can be proved mathematically as follows. Letting and for notational conciseness, the money supply can be written as a function of two variables defined over the domain . The partial derivatives of M with respect to both variables are positive, implying that this function is marginally increasing (i.e., considered as a function of either variable keeping the other constant) over its domain in both of its variables. Note that the domain of definition, which is determined by economic considerations, is crucial in establishing both the differentiability and the marginal monotonicity of .