Monotype Imaging

| |

| Public | |

| Traded as | NASDAQ: TYPE |

| Founded |

1887 (as Lanston Monotype Machine Company) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Headquarters | Woburn, Massachusetts, U.S. |

Key people |

Robert L. Lentz (Chairman)[1] |

| Website |

monotype |

Monotype Imaging Holdings, Inc. (NASDAQ: TYPE) is a Delaware corporation based in Woburn, Massachusetts. It specialises in digital typesetting and typeface design as well as text and imaging solutions for use with consumer electronics devices.[2] Monotype Imaging Holdings and its predecessors and subsidiaries have been responsible for many developments in printing technology—in particular the Monotype machine, which was the first fully mechanical typesetter, and the Linotype machine—and the design and production of typefaces in the 19th and 20th centuries. Monotype developed many of the most widely used typeface designs, including Times New Roman, Gill Sans, Arial, Bembo and Albertus.

Monotype has carried out a series of acquisitions from 2000 onwards of companies such as Linotype GmbH, International Typeface Corporation, Bitstream Inc. and FontShop. This has gained it the rights to many further widely known designs, including Helvetica, ITC Franklin Gothic, Optima, Avant Garde, Palatino and FF DIN. It also owns the MyFonts online retailer used by many independent font design studios.

History

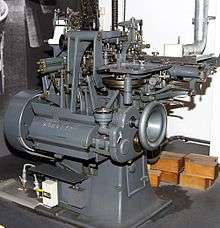

Monotype System

The Lanston Monotype Machine Company was founded by Tolbert Lanston in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1887. Lanston had a patented mechanical method of punching out metal types from cold strips of metal which were set (hence typesetting) into a matrix for the printing press. In 1896 Lanston patented the first hot metal typesetting machine and Monotype issued Modern Condensed, its first typeface. The licenses for the Lanston type library have been acquired by P22, a digital type foundry based in Buffalo, New York.

In a search for funding, the company set up a branch in London in 1897 under the name Lanston Monotype Corporation Ltd. In 1899 a new factory was built in Salfords near Redhill in Surrey where it has been located for over a century. The company was of sufficient size to justify the construction of its own Salfords railway station.

The Monotype machine worked by casting letters from "hot metal" (molten metal) as pieces of type. Thus spelling mistakes could be corrected by adding or removing individual letters. This was particularly useful for "quality" printing - such as books. In contrast, the Linotype machine formed a complete line of type in one bar. Editing these required replacing an entire line (and if the replacement ran onto another line, the rest of the paragraph). But Linotype slugs were easier to handle if moving a complete section of text around a page. This was more useful for "quick" printing - such as newspapers.

The typesetting machines were continually improved in the early years of the 20th century, with a typewriter style keyboard for entering the type being introduced in 1906. This arrangement addressed the need to vary the space between words so that all lines were the same length.

The keyboard operator types the copy, each key punching holes in a roll of paper tape that will control the separate caster. A drum on the keyboard indicates to the operator the space required for each line. This information is also punched in the paper. Before fitting the tape to the caster it is turned over so that the first holes read on each line set the width of the variable space. The subsequent holes determine the position of a frame, or die case, that holds the set of matrices for the face being used. Each matrix is a rectangle of copper recessed with the shape of the letter. Once the matrix is positioned over the mould that forms the rest of the piece of type being cast, molten type metal is injected.

Typefounding

Monotype's role in design history is not merely due to their supply of printing equipment but due to their commissioning of many of the most important typefaces of the twentieth century.

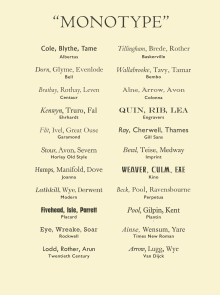

The company's first font of 1896 was a rather generic design, now named Modern, influenced by Bodoni and Scotch Roman designs. However, by the 1920s the company's British branch was well known for commissioning popular, historically influenced designs that revived some of the best typefaces of the past, with particular attention to the early period of printing from the Renaisssance to the late eighteenth-century.[3][4][5][6] This series of releases was a major part of the typographic renaissance of the period, an expansion of the arts and crafts movement interest in printing into the more workaday world of general-purpose printing. Key executives of the company in this period included historian and adviser Stanley Morison, publicity manager Beatrice Warde and engineering experts Frank Hinman Pierpont and Fritz Steltzer (both recruited from the German printing industry, although Pierpont was American), under managing director William Isaac Burch, who led the company from 1924 to 1942.[7] Despite tensions within the company, particularly between the historically minded faction of Morison and Warde and Pierpont in Salfords, notable typefaces commissioned included Gill Sans, Times New Roman and Perpetua, and the company maintained high standards of development allowing it to produce designs with good spacing, careful adaptation of the same basic design to different sizes and even colour on the page, essential qualities for balanced body text.[8][9][10][11]

Historian James Mosley, who worked closely with Monotype in the 1950s and onwards, has commented:

The English Monotype Corporation of the interwar years looks in retrospect rather like one of the great public bodies of the period, for example the British Broadcasting Corporation or London Transport…benevolent monopolies ruled by autocrats who revelled in the role of patron of the arts on a scale exceeding that of Italian Renaissance princes.

Monotype enjoyed, in Britain at least, something approaching a monopoly in book and better-quality magazine typesetting…Monotype exploited the glamour of its new typefaces…with brilliant publicity, for which Morison and his devoted young American recruit Beatrice Warde were partly responsible.[12]

To promote its image, the company ran a magazine, the Monotype Recorder, over most of the twentieth century, and also ran a compositor (typesetter operator) training school in London.[13] In 1936, the company was floated on the London Stock Exchange and became the Monotype Corporation Ltd.

The American branch lagged behind the British in artistic reputation. Their designs are now often rather obscure, since (unlike products from the British branch) few have been made widely available through bundling with Microsoft products. The company employed Frederic Goudy on several serif font projects which were well received at the time, and on staff type designer Sol Hess, who created the geometric sans-serif Twentieth Century as a competitor to the German Futura.[14][15][16][17]

Decline

.jpg)

Monotype entered a decline from the 1960s onwards. This was caused by the reduction in use of hot metal typesetting and replacement with phototypesetting and lithography in mass-market printing.[18][19][20] This offered considerable efficiencies, such as no need to print books from solid metal type, quicker setting of type and a reduced number of operators needed.[21][22] It also promised a more diverse and exciting range of fonts than that possible with hot metal, where it is necessary to own life-size matrices for every size of every font to be used.[23]

Monotype made the transition to cold type and began to market its own “Monophoto” phototypesetting systems, but these suffered from problems. Its first devices were heavily based on hot metal machinery, with glass pictures of characters which would be reproduced on photographic paper replacing the matrices used to cast metal type.[24][25] While this reduced the need for retraining, the resulting devices often set type slowly compared to legacy-free next-generation devices from providers such as Photon and Compugraphic, and were often more expensive. Its devices were slow to incorporate use of electronics, and while its type library was of high quality, changing tastes and the development of other companies’ libraries competed with this.[26] Its type library was also easily pirated, since fonts have only limited copyright protection. The company was eventually split into three divisions: Monotype International, which manufactured spinning mirror switched laser beam phototypesetters; Monotype Limited, which continued the hot metal machines; and Monotype Typography, which designed and sold typefaces. A research and development department was set up in Cambridge to isolate it from day to day production issues.

Monotype in the UK continued to enjoy prestige through the 1970s with the patronage of major British printers such as the university presses at Oxford and Cambridge; it also enjoyed some success with its Lasercomp laser-based typesetting system from the 1970s onwards, developed by the Cambridge research group.[26][27] However, new technology and finally publishing software such as Quark XPress and Aldus PageMaker running on general-purpose computers ate away at its competitiveness in the market of complete typesetting solutions by the 1990s.[28]

Monotype, however, has continued in business, for instance marketing typeface designs to third-party buyers, computing companies such as Microsoft (many fonts on Microsoft computers in particular are Monotype-designed) and companies and organisations such as London Transport and the UK parliament requiring custom digital typefaces.[29][30][31] Much of its metal type equipment and archives were donated to the Type Museum collection in London; other materials are held at St Bride Library.[32]

Consolidation and reorganization

In 1992 The Monotype Corporation Ltd. appointed Administrative Receivers on 5 March and four days later Monotype Typography Ltd. was established. Cromas Holdings, an investment company based in Switzerland, bought the Monotype Corporation Ltd. and Monotype Inc. (excluding Monotype Typography) and five other direct subsidiary companies in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Singapore. Monotype Systems Ltd. was the adopted name for the new organization with Peter Purdy as Chairman, the name Monotype was under license from Monotype Typography Ltd which retained the trademark Monotype. Monotype Systems Ltd. focused on selling pre-press software and hardware, raster image processors and workflow.

Cromas Holdings reorganized its publishing interests with the formation of the International Publishing Asset Holding Ltd. effectively controlling Monotype Systems Ltd., QED Technology Ltd., and GB Techniques Ltd.

Monotype Systems Ltd. purchased Berthold Communications; the UK subsidiary of the German composing equipment supplier.

In June 2002, Monotype Systems Limited was re-branded, IPA Systems Limited, as this marked the end of the existing trademark licence with Monotype Corporation. In the US Monotype Inc became alfaQuest Technologies Limited. Both companies still sell pre-press software and hardware.

In 1999, Agfa-Compugraphic acquired the Monotype Corporation, which was renamed Agfa Monotype. In late 2004, after six years under the Agfa Corporation, the Monotype assets were acquired by TA Associates, a private equity investment firm based in Boston. The company was incorporated as Monotype Imaging, with a focus on the company's traditional core competencies of typography and professional printing.

Monotype was the first company to produce a digital version of the handwritten Persian script, Persian Nasta'liq. A Chinese "keyboard" was developed to typeset Chinese characters; it consisted of a book with a stylus. As the pages were turned, the page number was detected electrically and this was combined with the position of the character selected by the stylus on a large grid.

In early 2000, Monotype launched Fontwise, the first software to audit desktops for licensed and unlicensed (not necessarily illegal) fonts.

On 2 October 2006, Monotype Imaging Inc. announced that it acquired Linotype GmbH, a subsidiary of Heidelberger Druckmaschinen AG.

On 18 September 2006, Monotype Imaging Inc. announced that it acquired China Type Design Limited, a typeface design and production company based in Hong Kong. CTDL was responsible for developing Microsoft JhengHei, the default traditional Chinese interface font for Windows Vista. The deal also secured an exclusive relationship with Creative Calligraphy Center (CCC), a font production company in Zhuhai, China, with 30 production specialists.

On 11 December 2009, Monotype Imaging Inc. announced that it acquired Planetweb, Inc., a developer specialized in applications and development tools for embedded devices.

On 8 December 2010, Monotype Imaging announced the acquisition of Ascender Corp., a provider of fonts and font technologies used in computers, mobile devices, consumer electronics and software products.

In March 2012, Monotype acquired Bitstream Inc., a digital font retailer. The deal also gave Monotype ownership of the MyFonts font sale website used by many independent designers and its WhatTheFont recognition service.[33]

On 15 July 2014, Monotype Imaging Inc. announced that it acquired FontShop, the last large independent digital font retailer.[34]

Typefaces

- Apollo

- Albertina (Chris Brand, 1966)

- Albertus (Berthold Wolpe, 1932–40)

- Albion (1910)

- Arial (Nicholas, Saunders et al., 1982)

- Ashley Crawford

- Ashley Script

- Bembo (1929)

- Blado

- Bodoni

- Bulmer

- Castellar

- Centaur (Rogers & Warde, 1929)

- Colonna

- Condensa

- Dante

- Ehrhardt

- Emerson

- Engravers

- Felix Titling

- Festival Titling

- Forte

- Fournier

- Gill Sans

- Goudy Old Style

- Horley Old Style

- Imprint

- Joanna

- Klang

- Matura

- Menhart

- Mercurius Script

- Monotype Grotesque

- Octavian

- Pastonchi (1928)[35][36]

- Pegasus

- Pepita

- Perpetua

- Photina

- Poliphilus

- Plantin

- Solus (Eric Gill, 1929)

- Spectrum

- Tempest Titling (Berthold Wolpe)

- Times New Roman

- Twentieth Century

- Van Dijck

- Walbaum

Divisions

- Monotype Imaging Inc.: Monotype's American headquarters in Woburn, Massachusetts.

- Monotype Imaging Ltd.: Monotype's UK branch in Surrey, England.

- Linotype GmbH: Monotype's European affiliate in Bad Homburg (Germany).

- China Type Design Ltd.: A typeface design and production company based in Hong Kong.

- Monotype Imaging K. K.: Monotype's Japanese branch in Tokyo.

See also

- Linotype typesetting machine

- Monotype typefaces, hot metal typefaces

- Monotype System

References

- ↑ "Board of Directors". Monotype Imaging. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ↑ 2008 SEC Annual Report:.

- ↑ McKitterick, David (2004). A history of Cambridge University Press. (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521308038.

- ↑ "Modern". MyFonts. Monotype. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Shinn, Nick. "Lacunae" (PDF). Codex. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Badaracco, Claire (1991). "Innovative Industrial Design and Modern Public Culture: The Monotype Corporation, 1922–1932" (PDF). Business & Economic History. Business History Conference. 20 (second series): 226–233. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Badaracco, Claire (1996). "Rational Language and Print Design in Communication Management". Design Issues. 12 (1): 26. doi:10.2307/1511743.

- ↑ "Fonts designed by Monotype Staff". Identifont. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Mosley, James (2001). "Review: A Tally of Types". Journal of the Printing History Society. 3, new series: 63–67.

The surviving records of the progress of some of the classic typefaces demonstrate that their exemplary final quality was due to a relentless willingness on the part of 'the works' to make and remake the punches over and over again until the result was satisfactory. The progression of series 270 from the weak Poliphilus Modernised to the familiar Bembo is an object lesson in the success of this technique. That it was [engineering manager Frank] Pierpont himself who was central to this drive for quality is made abundantly clear by the abrupt changes that are seen after his retirement in 1937.

- ↑ Rhatigan, Daniel (September 2014). "Gill Sans after Gill" (PDF). Forum (28): 3–7. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ↑ Rhatigan, Dan. "Time and Times again". Monotype. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Eric Gill's Perpetua Type". Fine Print.

- ↑ "Monotype Recorder back issues". Metal Type Library collection. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Goudy, Frederic (1946). A half-century of type design and typography, vol 1. New York: The Typophiles. pp. 121–124. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul. "An appreciation of Frederic W. Goudy as a type designer". Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Rogers, Bruce (January 1923). "Printer's Note". Monotype: A Journal of Composing Room Efficiency: 23.

This issue of Monotype is set in a trial font of a new version of Garamond's design ... the type ornaments, modelled on 16th century ones, will also be available.

- ↑ "LTC Garamont". MyFonts. LTC. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Third Tripartite Technical Meeting for the Printing and Allied Trades, Geneva, 1990. International Labour Organization. 1 January 1990. pp. 12–29. ISBN 978-92-2-107441-0.

- ↑ Reports of Tax Cases. H.M. Stationery Office. 1993. pp. 470–507.

- ↑ Simon Eliot; Jonathan Rose (24 August 2011). A Companion to the History of the Book. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 286–289. ISBN 978-1-4443-5658-8.

- ↑ United States. Bureau of Labor Statistics (1984). Occupational Outlook Handbook. Bureau of Labor Statistics. pp. 316–7.

- ↑ Philip G. Altbach; Edith S. Hoshino (8 May 2015). International Book Publishing: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-134-26126-0.

- ↑ Mosley, James (2003). "Reviving the Classics: Matthew Carter and the Interpretation of Historical Models". In Mosley, James; Re, Margaret; Drucker, Johanna; Carter, Matthew. Typographically Speaking: The Art of Matthew Carter. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 9781568984278. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ Helmut Kipphan (31 July 2001). Handbook of Print Media: Technologies and Production Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1045. ISBN 978-3-540-67326-2.

- ↑ The Monotype: How It Works. Monotype. 1957. pp. 10–16. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- 1 2 Boag, Andrew (2000). "Monotype and Phototypesetting" (PDF). Journal of the Printing History Society: 57–77. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Maw, Martin (November 2013). History of Oxford University Press: Volume III: 1896 to 1970. OUP Oxford. pp. 277–307. ISBN 978-0-19-956840-6.

- ↑ Romano, Frank. "The day the typesetting industry died". What They Think. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Castle, Bob; Carpenter, Victoria. "Book Antiqua Parliamentary (Freedom of Information request)". Whatdotheyknow.com. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ Walters, John; Esterson, Simon. "Features: Robin Nicholas". Eye magazine. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, Paul; Carter, Matthew. "Some history about Arial". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "The materials of typefounding". Type Foundry. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Shankland, Stephen. "Monotype gets more digital, buys Bitstream font biz". CNet. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Monotype Acquires FontShop International". Monotype. July 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Pastonchi". Fonts.com. Monotype. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Pastonchi: a specimen of a new letter for use on the Monotype". The Library. s4-IX (4): 421–422. 1928. doi:10.1093/library/s4-IX.4.421.

External links

Corporate information and official digital font releases:

- Official website

- China Type Design Limited

- Monotype online store

- customfonts by Monotype Imaging

- Fontwise

- FontExplorer X Pro - Client and Server Font Management

- Monotype Imaging Acquires Linotype

- IPA Systems Ltd

- alfaQuest Technologies Limited

P22 digitisations:

- Lanston Monotype fonts (digitised by P22)

On the Monotype System:

- Monotype keyboard and caster video lectures

- Metal Type - site on Monotype and other printing history, many diagrams, manuals and other documents

- Offizin Parnassia - Type Foundry

Metal and early phototype period publicity material:

- Metal Type website library section - archive material includes:

- Monotype Recorder - collection of digitised issues, not complete

- Monotype specimen sheet from the 1950s

Monotype fonts in metal type:

- The Press & Letterfoundry of Michael and Winifred Bixler - artisanal printing using a historic Monotype machine

- Monotype hot metal fonts from M & H Type

- Chestnut Press - other sample images

- British Printing Society

For specimen images of specific fonts, see individual Wikipedia articles.