Muslim minority of Greece

The Muslim minority of Greece is the only explicitly recognized minority in Greece. It numbers 97,605 (0.91% of the population) according to the 1991 census,[1] and 140,000 people or 1.24% of the total population, according to the United States Department of State.[2]

Like other parts of the southern Balkans that experienced centuries of Ottoman rule the Muslim minority of mainly Western Thrace in Northern Greece consists of several ethnic groups, some being Turkish and some Bulgarian-speaking Pomaks, with smaller numbers descended from Ottoman-era Greek converts to Islam. The precise identity of these groups is in contention with Turkey insisting that most Muslims in Western Thrace are ethnically Turkish, and Greece claiming many are Pomak and others of local origin who converted to Islam and adopted the Turkish language and identity in the Ottoman period. These arguments have territorial overtones, since the self-identity of the Muslims in Western Thrace could conceivably support territorial claims to the region by Turkey.[3]

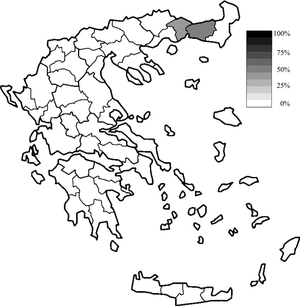

The Muslims of Western Thrace were exempt from the 1923 Population exchange between Greece and Turkey (when all of the 1.5 million surviving Anatolian Greeks or Pontic Greeks and Caucasus Greeks were required to leave Turkey, and the 356,000 Muslims outside of Thrace were required to leave Greece, including the Muslim Greek Vallahades of western Greek Macedonia. Consequently, most of the Muslim minority in Greece resides in the Greek region of Thrace, where they make up 28.88% of the population. Muslims form the majority in the Rhodope regional unit (51.77%) and sizable percentages in the Xanthi (41.19%) and Evros regional units (4.65%).[4]

Nearly 3,000 Turks remain on the island of Rhodes and 2,000 on the island of Kos, as the islands were part of the Italian Dodecanese when the population exchange between Turkey and Greece happened (and so were not included in it).[5]

Background

Under the Treaty of Lausanne, 1923, Greece and Turkey conducted a population exchange: all the Greek Orthodox Christians of Turkey would be resettled in Greece apart from the Greeks of Istanbul (Constantinople), Imbros (Gökçeada) and Tenedos (Bozcaada), and all Turks of Greece would be resettled in Turkey apart from the Muslims of Greek Thrace.[6]

The exchanged populations were not homogenous; the Christians resettled in Greece included not only Greek speakers, but also Georgian speakers, Arabic speakers and even Turkish speakers. Similarly, the Muslims resettled in Turkey included not only Turkish speakers, but also Albanian speakers, Bulgarian speakers, Vlach speakers and also Greek speakers like the Vallahades from western Greek Macedonia (see also Greek Muslims). This was in correspondence with the millet system of the Ottoman Empire, where religious and national allegiance coincided, and thus Greece and Turkey were considered the parent state of each group respectively.

In 1922, the Muslim minority left in Western Thrace, in Northern Greece, numbered approximately 86,000 people,[4] and consisted of four ethnic groups: Turks (here usually referred to as Western Thrace Turks), Pomaks (Muslim Slavs who speak Bulgarian), Muslim Roma, and Greek Muslims, each of these groups having its own language and culture. The official Greek text of the Treaty of Lausanne refers to "muslim minorities" in article 45[7] However, unofficial texts of the Greek State refer to one Muslim minority.[4] According to the Greek government, Turkish speakers form approximately 50% of the minority, Pomaks 35% and Muslim Roma 15%.[4]

The minority enjoys full equality with the Greek majority, and prohibition against discrimination and freedom of religion are provided for in Article 5 and Article 13 of the Greek constitution.[8] In Thrace today there are 3 muftis, approximately 270 imams and approximately 300 mosques.[9]

Politics

The minority is always represented in the Greek parliament,[9] and is currently represented by PASOK members Çetin Mandacı and Ahmet Hacıosman. During the 2002 local elections, approximately 250 Muslim municipal and prefectural councillors and mayors were elected, and the Vice-Prefect of Rhodope is also a Muslim.[9] The main minority rights activist organization of the Turkish community within the minority is the "Turkish Minority Movement for Human and Minority Rights" (Greek: Τούρκικη Μειονοτική Κίνηση για τα Ανθρώπινα και Μειονοτικά Δικαιώματα, Toúrkiki Meionotikí Kínisi yia ta Anthrópina kai Meionotiká Dikaiómata, Turkish: İnsan ve Azınlık Hakları için Türk Azınlık Hareketi).

Education

In Thrace today there are 235 minority primary schools, where education is in the Greek and Turkish languages,[4] and there are also two minority secondary schools, one in Xanthi and one in Komotini, where most of the minority is concentrated.[4] In the remote mountainous areas of Xanthi where the Pomak element is dominant, the Greek government has set up Greek language secondary education schools in which religious studies is taught in Turkish and the Quran is taught in Arabic.[4] The Pomak language (which is essentially considered a dialect of Bulgarian), however, is not taught at any level of the education system.[10] The government finances the transportation to and from the schools for students who live in remote areas, and in the academic year 1997-98, approximately 195,000 USD was spent on transportation.[4]

There are two Islamic theological seminaries, one in Komotini, and one in Echinos (a small town in Xanthi regional unit inhabited almost exclusively by Pomaks), and under Law 2621/1998, the qualification awarded by these institutions has been recognized as equal to that of the Greek Orthodox seminaries in the country.[4]

Finally, 0.5% of places in Greek higher education institutions are reserved for members of the minority.[9]

All the aforementioned institutions are funded by the state.[11]

Grievances

The main minority grievance regards the appointment of muftis. The Greek government started appointing muftis instead of holding elections after the death of Mufti of Komotini in 1985 (which is a failure to implement Law 2345/1920 according to Cultural Survival[12]), although the Greek government maintained that as the practice of state-appointed muftis is widespread (including in Turkey), this practice should be adhered to in Greece, and as the muftis perform certain judicial functions in matters of family and inheritance law, the state ought to appoint them.[4] Human Rights Watch alleges that this is against Lausanne Treaty which grants the Muslim minority the right to organize and conduct religious affairs free from government interference[13] (although it is unclear whether issues such as inheritance law are religious matters). As such, there are two muftis for each post, one elected by the participating faithful, and one appointed by Presidential Decree. The elected Mufti of Xanthi is Mr Aga and the government recognized one is Mr Sinikoğlu; the elected Mufti of Komotini is Mr Şerif and the government recognized one is Mr Cemali. According to the Greek government, the elections by which Mr Aga and Mr Şerif were appointed were rigged and involved very little participation from the minority.[4] As pretension of (religious) authority is a criminal offence against the lawful muftis under the Greek Penal Code, both elected muftis were prosecuted and on conviction, both were imprisoned and fined. When, however, the case was taken to the European Court of Human Rights, the Greek government was found to have violated the right to religious freedom of Mr Aga and Mr Şerif.[14]

Another controversial issue was Article 19 of the Greek Citizenship Code, which allowed the government to revoke the citizenship of non-ethnic Greeks who left the country. According to official statistics 46,638 Muslims (most of them being of Turkish origin) from Thrace and the Dodecanese islands lost their citizenships from 1955 to 1998, until the law was non-retroactively abolished in 1998.[15]

The final grievance is the Greek government's restrictions on the usage of the terms "Turk" and "Turkish" when describing the minority as a whole. A number of organizations, including the "Turkish Union of Xanthi", have been banned for using those terms in their title.[8] In 2008 after a decision of the European Court of Human Rights ruled the re-legalization of the association and convicted Greece of violating the freedom of association, however, the Greek authorities refused to re-legalize it.[16]

See also

- Minorities in Greece

- Demographics of Greece

- Turks of Western Thrace

- Turks of the Dodecanese

- Provisional Government of Western Thrace

- Pomaks

- Treaty of Lausanne

- 1990 Komotini events

References

- ↑ Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών, Υπηρεσία Ενημέρωσης: Μουσουλμάνικη μειονότητα Θράκης and Ελληνική Επιτροπή για τη διαχείρηση των υδατικών πόρων: Στοιχεία από την πρόσφατη απογραφή του πληθυσμού

- ↑ (English) US Department of State - Religious Freedom, Greece

- ↑ See Hugh Poulton, 'The Balkans: minorities and states in conflict', Minority Rights Publications, 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών, Υπηρεσία Ενημέρωσης: Μουσουλμάνικη μειονότητα Θράκης

- ↑ Moslem Turkish teacher born in Rhodes

- ↑ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Convention_Concerning_the_Exchange_of_Greek_and_Turkish_Populations

- ↑ Treaty of Lausanne. Part 1, Peace Treaty. Article 45: "Τα αναγνωρισθέντα δια των διατάξεων του παρόντος Τμήματος δικαιώματα εις τας εν Τουρκία μη μουσουλμανικάς μειονότητας, αναγνωρίζονται επίσης υπό της Ελλάδος εις τας εν τω εδάφει αυτής ευρισκομένας μουσουλμανικάς μειονότητας".

"The rights which are recognized hereby for the non-muslim minorities living in Turkey, are also recognized by Greece for the muslim minorities on Greek territory." - 1 2 Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, by the Greek Helsinki Monitor, 18 September 1999

- 1 2 3 4 Μuslim Minority of Thrace by the Greek ministry of foreign affairs

- ↑ Report on the Pomaks, by the Greek Helsinki Monitor

- ↑ United States Department of State: International Religious Freedom Report 2006

- ↑ Vestiges of the Ottoman Past: Muslims Under Siege in Contemporary Greek Thrace

- ↑ Human Rights Watch: The Turks of Western Thrace

- ↑ The case of Mehmet Emin Aga

- ↑ Press Release of Federation of Western Thrace Turks in Europe and HRW World Report 1999: Greece:Human Rights Developments

- ↑ 2009 Human Rights Report: Greece U.S Department of State

Further reading

- Antoniou, Dimitris A. (July 2003). "Muslim Immigrants in Greece: Religious Organization and Local Responses". Immigrants and Minorities. 22 (2–3): 155–174. doi:10.1080/0261928042000244808.

External links

- Ramadanoglou case Greece Helsinki Monitor