Nacht und Nebel

Nacht und Nebel [ˈnaχt ʊnt ˈneːbəl] (German for "Night and Fog") was a directive (German: Erlass) from Adolf Hitler on 7 December 1941 targeting political activists and resistance "helpers" that was originally intended to winnow out "anyone endangering German security" (die deutsche Sicherheit gefährden) throughout Nazi Germany's occupied territories. Its name was a direct reference to a Tarnhelm spell, from Wagner's Das Rheingold.

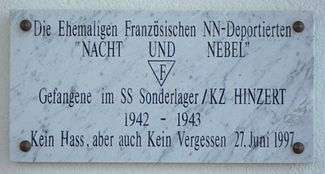

Three months later Armed Forces High Command Feldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel expanded it to include all persons in occupied countries who had been taken into custody; if they were still alive eight days later, they were to be handed over to the Gestapo.[1] The decree was meant to intimidate local populations into submission, by denying friends and families of seized persons any knowledge of their whereabouts or their fate. The prisoners were secretly transported to Germany, and vanished without a trace. In 1945, the abandoned Sicherheitsdienst (SD) records were found to include merely names and the initials "NN" (Nacht und Nebel); even the sites of graves were unrecorded. The Nazis even coined a new term for those who "vanished" in accordance with this decree; they were vernebelt—"transformed into mist".[2] To this day, it is not known how many thousands of people disappeared as a result of this order.[3]

The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg held that the disappearances committed as part of the Nacht und Nebel program were war crimes which violated both the Hague Conventions and customary international law.[4]

Background

Even before the Holocaust gained momentum, the Nazis had begun rounding up political prisoners from both Germany and occupied Europe. Most of the early prisoners were of two sorts: they were either prisoners of personal conviction (belief), political prisoners whom the Nazis deemed in need of "re-education" to Nazi ideals, or resistance leaders in occupied western Europe.[5] Up until the time of the Nacht und Nebel decree, prisoners from Western Europe were handled by German soldiers in approximately the same way as other countries: according to international agreements and procedures such as the Geneva Convention.[6] Hitler and his upper level staff, however, made a critical decision not to conform to what they considered unnecessary rules and in the process abandoned "all chivalry towards the opponent" and removed "every traditional restraint on warfare."[7]

On 7 December 1941, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler issued the following instructions to the Gestapo:

After lengthy consideration, it is the will of the Führer that the measures taken against those who are guilty of offenses against the Reich or against the occupation forces in occupied areas should be altered. The Führer is of the opinion that in such cases penal servitude or even a hard labor sentence for life will be regarded as a sign of weakness. An effective and lasting deterrent can be achieved only by the death penalty or by taking measures which will leave the family and the population uncertain as to the fate of the offender. Deportation to Germany serves this purpose.[8]

On 12 December, Keitel issued a directive which explained Hitler's orders:

Efficient and enduring intimidation can only be achieved either by capital punishment or by measures by which the relatives of the criminals do not know the fate of the criminal.

He further expanded on this principle in a February 1942 letter stating that any prisoners not executed within eight days were:

to be transported to Germany secretly, and further treatment of the offenders will take place here; these measures will have a deterrent effect because - A. The prisoners will vanish without a trace. B. No information may be given as to their whereabouts or their fate.

Himmler immediately communicated Keitel's directive to various SS stations and within six months the decree was sent to concentration camp commanders by Richard Glücks.[9] The Nacht und Nebel prisoners were mostly from France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway.[10] They were usually arrested in the middle of the night and quickly taken to prisons hundreds of miles away for questioning, eventually arriving at concentration camps such as Natzweiler, Esterwegen or Gross-Rosen, if they survived.[11][12] Natzweiler concentration camp in particular, became an isolation camp for political prisoners from northern and western Europe under the decree's mandate.[13] Up to 30 April 1944, at least 6,639 persons were captured under the Nacht und Nebel orders.[14] Some 340 of them may have been executed. The 1955 film Night and Fog, directed by Alain Resnais, uses the term to illustrate one aspect of the concentration camp system as it was transformed into a system of labour and death camps.

Text of the decrees

Directives for the prosecution of offences committed within the occupied territories against the German State or the occupying power, of 7 December 1941.

Within the occupied territories, communistic elements and other circles hostile to Germany have increased their efforts against the German State and the occupying powers since the Russian campaign started. The amount and the danger of these machinations oblige us to take severe measures as a deterrent. First of all the following directives are to be applied:

I. Within the occupied territories, the adequate punishment for offences committed against the German State or the occupying power which endanger their security or a state of readiness is on principle the death penalty.

II. The offences listed in paragraph I as a rule are to be dealt with in the occupied countries only if it is probable that sentence of death will be passed upon the offender, at least the principal offender, and if the trial and the execution can be completed in a very short time. Otherwise the offenders, at least the principal offenders, are to be taken to Germany.

III. Prisoners taken to Germany are subject to military procedure only if particular military interests require this. In case German or foreign authorities inquire about such prisoners, they are to be told that they have been arrested but that the proceedings do not allow any further information.

IV. The Commanders in the occupied territories and the Court authorities within the framework of their jurisdiction, are personally responsible for the observance of this decree.

V. The Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces determines in which occupied territories this decree is to be applied. He is authorized to explain and to issue executive orders and supplements. The Reich Minister of Justice will issue executive orders within his own jurisdiction.[15][16]

Rationale

The reasons for Nacht und Nebel were many. The policy, enforced in Nazi-occupied countries, meant that whenever someone was arrested, the family would learn nothing about the person's fate. The people arrested, sometimes only suspected resistors, were secretly sent to Germany and perhaps to a concentration camp. Whether they lived or died, the Germans would give out no information to the families involved.[17] This was done to keep the population in occupied countries quiet by promoting an atmosphere of mystery, fear and terror.[18][19]

The program made it far more difficult for other governments or humanitarian organizations to accuse the German government of specific misconduct because it obscured whether or not internment or death had even occurred, let alone the cause of the person's disappearance. It thereby kept the Nazis from being held accountable. It allowed across-the-board, silent defiance of international treaties and conventions – one cannot apply the requirements for humane treatment in war if one cannot locate a victim or discern that victim's fate. Additionally, the policy lessened German subjects' moral qualms about the Nazi regime, as well as their desire to speak out against it, by keeping the general public ignorant of the regime's malfeasance and by creating extreme pressure for service members to remain silent.[20]

Treatment of prisoners

The Nacht und Nebel prisoners' hair was shaved and the women were given a convict costume of a thin cotton dress, wooden sandals and a triangular black headcloth. According to historian Wolfgang Sofsky,

Prisoners of the Nacht und Nebel transports were marked by broad red bands; on their backs and both trouser legs was a cross, with the letters “NN” to its right. From these emblems, it was possible to recognize immediately what class a prisoner belonged to and how he or she was pigeonholed and evaluated by the SS.[21]

The prisoners were often moved apparently at random from prison to prison such as Fresnes Prison in Paris, Waldheim near Dresden, Leipzig, Potsdam, Lübeck and Stettin. The deportees were sometimes herded 80 at a time with standing room only into slow moving, dirty cattle trucks with little or no food or water on journeys lasting up to five days to their next unknown destination.[22]

At the camps, the prisoners were forced to stand for hours in freezing and wet conditions at 5:00am every morning, standing strictly to attention, before being sent to work a twelve-hour day with only a twenty-minute break for a scant meal. They were confined in cold and starving conditions; many had dysentery or other illnesses, and the weakest were often beaten to death, shot, guillotined, or hanged, while the others were subjected to torture by the Germans.[23] When the inmates were totally exhausted or if they were too ill or too weak to work, they were then transferred to the Revier ("Krankenrevier", sick barrack) or other places for extermination. If a camp did not have a gas chamber of its own, the so-called Muselmänner, or prisoners who were too sick to work, were often killed or transferred to other concentration camps for extermination.[23]

When the Allies liberated Paris and Brussels, the SS transported many of its remaining Nacht und Nebel prisoners to concentration camps deeper in Nazi-controlled territory, such as Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, Buchenwald concentration camp, Schloss Hartheim, or Flossenbürg concentration camp.[24]

Results

Early in the war, the program caused the mass execution of political prisoners, especially Soviet military prisoners, who in early 1942 outnumbered the Jews in number of deaths even at Auschwitz.[25] As the transports grew and Hitler's troops moved across Europe, that ratio changed dramatically. The Nacht und Nebel decree was carried out surreptitiously, but it set the background for orders that would follow and established a "new dimension of fear".[26] As the war continued, so did the openness of such decrees and orders.

It can be surmised from various writings that in the beginning the German public knew only a little of the plans Hitler had to enforce a "New European Order". As the years passed, despite the best attempts of Goebbels and the Propaganda Ministry with its formidable domestic information control, diaries and periodicals of the time show that information about the harshness and cruelty of the program became progressively known to the German public.[27]

Soldiers brought back information, families on rare occasion heard from or about loved ones, and Allied news sources and the BBC were able to get past censorship sporadically.[28] Although captured archives from the SD contain numerous orders stamped with "NN" (Nacht und Nebel), it has never been determined exactly how many people disappeared as a result of the decree. Hesitant if not outright skeptical at first of reports coming in about the atrocities being committed by the Germans, the Allies' doubts were pushed aside when the French entered the Natzweiler-Struthoff camp (one of the Nacht und Nebel facilities) on 23 November 1944 and discovered a chamber where victims were hung by their wrists from hooks to accommodate the process of pumping Zyklon-B gas into the room.[29] Keitel later testified at the Nuremberg Trials that of all the illegal orders he had carried out, the Nacht und Nebel decree was "the worst of all".[30]

Former Supreme Court Justice and chief prosecutor at the international Nuremberg trial, Robert H. Jackson listed the "terrifying" Nacht und Nebel decree with the other horrid crimes committed by the Nazis in his closing address.[31] In part because of his role in carrying out this decree, Keitel was sentenced to death by hanging, despite his insistence on being shot instead due to his military service and rank.[32] At 1:20am on 16 October 1946 Keitel shouted out, "Alles für Deutschland! Deutschland über alles!" just before the trap door opened beneath his feet.[33]

Notable prisoners

- Pim Boellaard (Dutch Resistance)

- Trygve Bratteli (Norwegian Resistance, later Prime Minister)

- Virginia d'Albert-Lake (American)

- Charles Delestraint (French Resistance)

- Nadine Dumon (Belgian Resistance)[34]

- Andrée de Jongh ("Dédée") (Belgian Resistance)

- Noor Inayat Khan

- Mary Lindell (Comtesse de Milleville)

- Henriette Bie Lorentzen

- Elsie Maréchal (Belgian Resistance)

- Maurice Orcher (Belgian Resistance)

- Henriette Roosenburg

- Xavier, Duke of Parma

See also

- Commando Order

- Commissar Order

- Le prisonnier politique - a 1949 sculpture

- Resistance during World War II

- List of Nazi-German concentration camps

- Black jails (China)

- Extraordinary rendition (US)

- Forced disappearance

- Ghost detainee (War on Terror)

- National Defense Authorization Act (US)

- Without the right of correspondence (USSR)

- Night and Fog (1955 film)

- The Walls Came Tumbling Down (1957 book)

- List of books about Nazi Germany

References

- Notes

- ↑ Nürnberger Dokumente, PS-1733, NOKW-2579, NG-226. Cited in Bracher (1970). The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism, p. 418.

- ↑ Conot (2000). Justice at Nuremberg, p. 300.

- ↑ Manchester (2003). The Arms of Krupp, 1587–1968, p. 519.

- ↑ "Enforced Disappearance as a Crime Under International Law: A Neglected Origin in the Laws of War" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- ↑ Spielvogel (1992). Hitler and Nazi Germany: A History, pp. 82–120, pp. 232–264.

- ↑ Dülffer (2009). Nazi Germany 1933–1945: Faith and Annihilation, pp. 160–163.

- ↑ Walter Görlitz, "Keitel, Jodl, and Warlimont," cited in Barnett ed., (2003). Hitler’s Generals, p. 152.

- ↑ Crankshaw (1956). Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny, p. 215.

- ↑ Mayer (2012). Why Did the Heavens Not Darken?: The “Final Solution” in History, pp. 337-338.

- ↑ "Night and Fog Decree". ushmm.org. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Night and Fog Decree".

- ↑ Kogon (2006). The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System behind Them, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Overy (2006). The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Russia, p. 605.

- ↑ Lothar Gruchmann: "Nacht- und Nebel-"Justiz... In: VfZ 29 (1981), S. 395.

- ↑ "Nacht und Nebel decree (English translation)".

- ↑ United States, Office of United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality, Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, 8 vols. and 2 suppl. vols. VII, 873–874 (Doc. No. L-90). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946–1948.

- ↑ Stackelberg (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany, p. 286.

- ↑ Crankshaw, Edward (1990) [1956]. Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny, London: Greenhill Books. p. 204.

- ↑ Kaden & Nestler (1993). "Erlass Hitlers über die Verfolgung von Strafteten gegen das Reich, 7 December 1941." Dokumente des Verbrechens: Aus den Akten des Dritten Reiches, vol i, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Kammer & Bartsch (1999). "Nacht und Nebel Erlaß," in Lexikon Nationalsozialismus: Begriffe, Organisationen und Institutionen, p. 160.

- ↑ Sofsky (1997). The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp, p. 118.

- ↑ "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 6". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- 1 2 Nichol, John and Rennell, Tony (2007). Escape from Nazi Europe, Penguin Books.

- ↑ (English) Marc Terrance (1999). Concentration Camps: Guide to World War II Sites. Universal Publishers. ISBN 1-58112-839-8.

- ↑ Matthäus (2004), "Operation Barbarossa and the Onset of the Holocaust, June – December 1941," in Browning & Matthäus (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939– March 1942, pp. 259–264.

- ↑ Taylor & Shaw (2002). "Nacht und Nebel," in Dictionary of the Third Reich, p. 192.

- ↑ Gellately (2001). Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany, pp. 51–69.

- ↑ Johnson (2006). What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder, and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany, pp. 185–225.

- ↑ Lowe (2012). Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II, p. 81.

- ↑ Shirer (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p. 957.

- ↑ Marrus (1997). The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, 1945–46: A Documentary History, p. 151.

- ↑ Conot (2000). Justice at Nuremberg, p. 501.

- ↑ Conot (2000). Justice at Nuremberg, p. 506.

- ↑ "March 2007 - Escape or die: The untold WWII story". Daily Mail. 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

Bibliography

- Barnett, Correlli, ed., (2003). Hitler’s Generals. New York: Grove Press.

- Bracher, Karl Dietrich (1970). The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. New York: Praeger Publishers.

- Browning, Christoper, and Jürgen Matthäus (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939–March 1942. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Conot, Robert E. (2000) [1983]. Justice at Nuremberg. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers.

- Crankshaw, Edward (1990). Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny. London: Greenhill Books.

- Dülffer, Jost (2009). Nazi Germany 1933-1945: Faith and Annihilation. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gellately, Robert (2001). Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Johnson, Eric (2006). What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder, and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany. New York: Basic Books.

- Kaden, Helma, and Ludwig Nestler, eds., (1993). Dokumente des Verbrechens: Aus den Akten des Dritten Reiches. 3 Bände. Vol i. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

- Kammer, Hilde and Elisabet Bartsch (1999). Lexikon Nationalsozialismus: Begriffe, Organisationen und Institutionen (Rororo-Sachbuch). Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch.

- Kogon, Eugen (2006) [1950]. The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System behind Them. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-37452-992-5

- Lowe Keith (2012). Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II. New York: Picador.

- Manchester, William (2003). The Arms of Krupp, 1587-1968: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Dynasty that Armed Germany at War. New York & Boston: Back Bay Books.

- Mayer, Arno (2012) [1988]. Why Did the Heavens Not Darken?: The “Final Solution” in History. London & New York: Verso Publishing.

- Overy, Richard (2006). The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Russia. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39332-797-7

- Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: MJF Books. Originally published in [1959]. Drawing upon Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, part of the Nuremberg Documents, Vol. VII, pages 871-874, Nuremberg Document L-90.

- Sofsky, Wolfgang (1997). The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp. Translated by William Templer. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Spielvogel, Jackson (1992). Hitler and Nazi Germany: A History. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Stackelberg, Roderick (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge.

- Taylor, James, and Warren Shaw (2002) Dictionary of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin.

- Toland, John (1976). Adolf Hitler. New York: Doubleday.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (2014). Holocaust Encyclopedia, "Night and Fog Decree"

- Further reading

- Harthoorn, Willem Lodewijk. Verboden te sterven, Van Gruting, 2007, ISBN 978-90-75879-37-7 – A personal account of a person who survived as a "Night and Fog" prisoner four months in Gross-Rosen and a year in Natzweiler

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Night and Fog program. |

- Nacht und Nebel decree (English translation)

- "Nacht Und Nebel" Wiesenthal Center

- Hassall, Peter D. "Night and Fog Prisoners or Lost in the Night and Fog or The Unknown Prisoners"

.jpg)