1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake

| |

| |

| Date | 3 February 1931 |

|---|---|

| Origin time | 00:10:47 NZDT |

| Magnitude | 7.8 Ms |

| Depth | 20 km (12 mi) |

| Epicenter | 39°18′S 177°00′E / 39.3°S 177.0°ECoordinates: 39°18′S 177°00′E / 39.3°S 177.0°E |

| Areas affected | New Zealand |

| Casualties | 256 dead, thousands injured |

The 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake, also known as the Napier earthquake, occurred in New Zealand at 10:47 am on 3 February, killing 256,[1] injuring thousands and devastating the Hawke's Bay region. It remains New Zealand's deadliest natural disaster. Centred 15 km north of Napier, it lasted for two and a half minutes and measured magnitude 7.8 Ms (magnitude 7.9 Mw). There were 525 aftershocks recorded in the following two weeks, with 597 being recorded by the end of February. The main shock could be felt in much of New Zealand, with reliable reports coming in from as far south as Timaru, on the east coast of the South Island.[2]

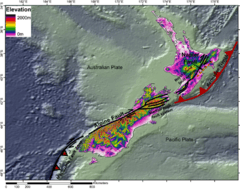

Tectonic setting

New Zealand lies along the boundary between the Indo-Australian Plate and Pacific Plates. In the South Island most of the relative displacement between these plates is taken up along a single dextral (right lateral) strike-slip fault with a major reverse component, the Alpine Fault. In the North Island the displacement is mainly taken up along the Hikurangi Subduction Zone, although the remaining dextral strike-slip component of the relative plate motion is accommodated by the North Island Fault System (NIFS).[3]

The earthquake is thought to have occurred on one of the larger thrust faults within the accretionary wedge, at between ca. 5 km depth and ca. 20–25 km depth (which is the approximate depth of subducted Pacific plate at that location).[4]

Effects

Nearly all buildings in the central areas of Napier and Hastings were levelled (The Dominion noted that "Napier as a town has been wiped off the map")[5] and the death toll included 161 people in Napier, 93 in Hastings, and two in Wairoa.[1] Thousands more were injured, with over 400 hospitalised.

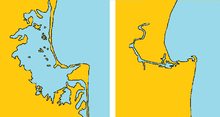

The local landscape changed dramatically, with the coastal areas around Napier being lifted by around two metres.[5] The most noticeable land change was the uplifting of some 40 km² of sea-bed to become dry land. This included Ahuriri Lagoon, which was lifted more than 2.7 metres[5] and resulted in draining 2230 hectares of the lagoon. Today, this area is the location of Hawkes Bay Airport, housing and industrial developments and farmland.

Within minutes fires broke out in chemist shops in Hastings Street, Napier. The fire brigade almost had the first fire under control when the second broke out in a shop at the back of the Masonic Hotel. The hotel was quickly engulfed in flames. The wind at this point also picked up strength and began blowing from the east, pushing the fires back over the city. With water mains broken, the brigade was unable to save many buildings. Pumping water from Clive Square, they were able to stop the fires spreading south. Only a few buildings in the central Napier area survived. Some withstood the earthquake only to be gutted by fire. Trapped people had to be left to burn as people were unable to free them in time. By Wednesday morning, the main fires were out, but the ruins still smouldered for several days.

In Hastings, the fires were quickly brought under control.

The death toll might have been much higher had the Royal Navy ship HMS Veronica not been in port at the time. Within minutes of the shock the Veronica had sent radio messages asking for help. The sailors joined survivors to fight the fires, rescue trapped people and help give them medical treatment. The Veronica's radio was used to transmit news of the disaster to the outside world and to seek assistance. The crew from two cargo ships, the Northumberland and Taranaki, also joined the rescue works, while two cruisers, HMS Diomede and HMS Dunedin, were dispatched from Auckland that afternoon with food, tents, medicine, blankets, and a team of doctors and nurses. The cruisers sailed at high speed overnight, arrived on 4 February and provided valuable assistance in all areas until their departure on 11 February.

A group of prisoners working at Bluff Hill in Napier had four of their number buried in a landslip by the quake. The remaining prisoners dug them out, but two had been killed. The prisoners re-assembled without any attempt to escape and were locked up in the Napier Jail. In Taradale, Mission Estate missionaries' accommodation block had been built and opened in February 1931. The next day the Hawke's Bay earthquake struck, causing serious damage to the entire Mission. Two priests and seven students were killed when the stone chapel was destroyed. In Havelock North, St Luke's church was damaged (but not destroyed) just before a wedding was due to take place. The couple got married later in the day, but outdoors.

Within four days of the quake, cinemas around New Zealand offered news specials about the disaster.

Another casualty of the earthquake was the Napier trams. The tracks were twisted by the earthquake, and were never restored.[6]

New Zealand's first commercial air disaster occurred six days after the quake, when a Dominion Airlines Desoutter monoplane crashed near Wairoa. The small airline had been making three return trips a day between Hastings and Gisborne, carrying passengers and supplies. All three on board were killed.

The Napier Daily Telegraph had recently celebrated its diamond jubilee with an article describing Napier as "the Nice of the Pacific". The newspaper office was destroyed by the quake. The Hawke's Bay Herald offices in Hastings were also destroyed.

It is still possible to see the original path of the earthquake from Napier Prison.[7]

Aftershocks

On 13 February, Hawke's Bay was struck by a 7.3 Ms aftershock. At the time, this second event was New Zealand’s fourth strongest recorded earthquake. Author Matthew Wright reported that "the power failed three seconds before the earthquake was felt in Napier. People from Napier to Dannevirke ran for their lives as previously damaged buildings cracked and fell".[8] He added "Some inland parts of Hawke’s Bay felt this aftershock more strongly than the 3 February quake. In Taupo, goods were thrown from shop shelves, but ‘there was no damage of any moment’. People rushed into the streets in Dannevirke and Masterton. In Wellington all but one of the clocks stopped working in the Dominion Observatory, and ceiling lights in the Evening Post offices swayed ‘more vigorously’ than they had the week before".[8] The earthquake of 13 February 1931 is widely regarded as an aftershock of the larger event ten days earlier. But Messrs Adams, Barnett and Hayes commenting on the rapid decline in the frequency of aftershocks in the Journal of Science & Technology stated, “The fresh outbreak on the 13th February, due to the severe shock on that date, may almost be regarded as a separate disturbance, although it probably arose from conditions produced by the original shock on the 3rd”.

Aftershocks continued to shake Hawke's Bay frequently until July 1931, where the average aftershock occurrence dropped to less than one daily. Aftershocks continued for several years, with the last major jolt shaking the Bay in April 1934.

Below is a list of all recorded aftershocks following the main event.

| Year | Month | Date | Number of Aftershocks | Major Aftershocks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1931 | February | 597 | ||

| 3 February | 151 | 5.5Ms | ||

| 4 February | 55 | |||

| 5 February | 50 | |||

| 6 February | 29 | |||

| 7 February | 24 | |||

| 8 February | <20 | 6.4Ms | ||

| 9 February | <20 | |||

| 10 February | <20 | |||

| 11 February | <20 | |||

| 12 February | <20 | |||

| 13 February | 81 | 7.3Ms | ||

| 14 February | 23 | |||

| 15 February | 18 | |||

| 16 February | 19 | |||

| 1931 | March | 75 | ||

| 1931 | April | 52 | 5.5Ms | |

| 1931 | May | 40 | 6.0Ms | |

| 1931 | June | 40 | ||

| 1931 | July | 26 | ||

| 1931 | August | 17 | ||

| 1931 | September | 20 | ||

| 1931 | October | 16 | ||

| 1931 | November | 19 | ||

| 1931 | December | 14 | ||

| 1932 | May | 5.9Ms | ||

| 1932 | September | 6.9Ms | ||

| 1934 | March | 6.3Ms | ||

| 1934 | April | 5.6Ms |

In all, 597 earthquakes were recorded at Hastings during February 1931, and more than 900 by the end of December 1931.[8][9]

Rebuilding

The government quickly realised that the Napier borough council would be overwhelmed with organising the rebuild and appointed two commissioners for this task, John Barton and L. B. Campbell.[10] When the commissioners were due to leave in May 1933, they were petitioned to stay, and Barton was invited to stand for the mayoralty, which he declined.[11]

The earthquake prompted a thorough review of New Zealand building codes, which were found to be totally inadequate. Many buildings built during the 1930s and 1940s are heavily reinforced, although more recent research has developed other strengthening techniques. Building regulations established as a result of this event mean that to this day, there are only four buildings in Hawke's Bay taller than five storeys, and as most of the region's rebuilding took place in the 1930s when Art Deco was fashionable, Hawke's Bay architecture is regarded today as being one of the finest collections of Art Deco in the world.

On the tenth anniversary of the earthquake, the New Zealand Listener reported that Napier had risen from the ashes like a phoenix. It quoted the 1931 principal of Napier Girls' High School as saying "Napier today is a far lovelier city than it was before".

See also

- List of earthquakes in 1931

- List of earthquakes in New Zealand

- List of New Zealand disasters by death toll

Notes

- 1 2 The exact number of deaths varies according to different sources; the New Zealand Listener article cited below gives 258 deaths, but the Bateman New Zealand Encyclopedia gives 256. The difference is due to two people "missing" and presumed dead. Some articles add these two to the death toll, while others do not.

- ↑ http://www.geonet.org.nz/quakes/region/newzealand/2178228

- ↑ Mouslopoulou,V., Nicol,A., Little, T.A. & Walsh, J.J. 2007. Terminations of large strike-slip faults: an alternative model from New Zealand. In: Cunningham, W. D. & Mann, P (eds).Tectonics of Strike-Slip Restraining and Releasing Bends. Geological Society of London, Special Publication, 290; p. 387–415.

- ↑ GNS Media release BAY QUAKE HIGHLIGHTS NZ’S VULNERABILITY 2 FEBRUARY 2001

- 1 2 3 New Zealand Historical Atlas - McKinnon, Malcolm (Editor); David Bateman, 1997, Plate 87

- ↑ "Napier Earthquake". Christchurch City Libraries. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ↑ Napier Prison - Napier Prison Tours & Events Retrieved January 2012

- 1 2 3 "Hawke's Bay Earthquakes 1931 « Wild Land". Wildland.owdjim.gen.nz. 2006-02-13. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ Alan G. Hull (1990) Tectonics of the 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake, New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 33:2, 309–320, DOI:10.1080/00288306.1990.10425689

- ↑ McSaveney, Eileen (13 July 2012). "Historic earthquakes - Rebuilding Napier". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Axford, C. Joy. "John Saxon Barton". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

References

- Welch, Denis (4 February 2006). "Shake, Rattle & Roll". New Zealand Listener (3430): 29–30. Retrieved 19 February 2006.

- "Earthquakes". History of Earthquakes in Hawke's Bay. Hawke's Bay Regional Council. Archived from the original on 29 January 2006. Retrieved 2006-02-20.

- "Hawke's Bay Earthquake 3 February 1931". Hastings District Libraries. Archived from the original on 2005-12-21. Retrieved 2006-02-20.

- Bateman New Zealand Encyclopedia, edition 4 (1995). Article: Napier

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake. |