Naproxen

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /nəˈprɒksən/ |

| Trade names | Aleve, Anaprox, Apronax, Naprelan, Naprosyn |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a681029 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral. |

| ATC code | G02CC02 (WHO) M01AE02 (WHO), M02AA12 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 95% (oral) |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (to 6-desmethylnaproxen) |

| Biological half-life | 12–24 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

22204-53-1 |

| PubChem (CID) | 156391 |

| DrugBank |

DB00788 |

| ChemSpider |

137720 |

| UNII |

57Y76R9ATQ |

| KEGG |

D00118 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:7476 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL154 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.040.747 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

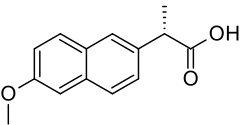

| Formula | C14H14O3 |

| Molar mass | 230.259 g/mol |

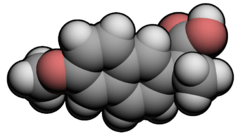

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 152–154 °C (306–309 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Naproxen (brand names: Aleve, Naprosyn, and many others) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) of the propionic acid class (the same class as ibuprofen) that relieves pain, fever, swelling, and stiffness.[2][3]:665,673 It is a nonselective COX inhibitor, usually sold as the sodium salt.

Naproxen poses an intermediate risk of stomach ulcers compared to ibuprofen, which is low-risk, and indometacin, which is high-risk.[4] To reduce stomach ulceration risk, it is often combined with a proton-pump inhibitor (a medication that reduces stomach acid production) during long-term treatment of those with pre-existing stomach ulcers or a history of developing stomach ulcers while on NSAIDs.[2][3]:665,673

Medical uses

Naproxen is commonly used to reduce pain, fever, inflammation, and stiffness caused by conditions such as migraine, osteoarthritis, kidney stones, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, ankylosing spondylitis, menstrual cramps, tendinitis, and bursitis. It is also used to treat primary dysmenorrhea.[5]

Diagnostics

Naproxen has been used to differentiate between infectious fevers and neoplastic or connective tissue disease-related fevers.[6]

Adverse effects

COX-2 selective and nonselective NSAIDs have been linked to increases in the number of serious and potentially fatal cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarctions and strokes. Naproxen is, however, associated with the smallest overall cardiovascular risks.[7][8] Cardiovascular risk must be considered when prescribing any nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. The drug had roughly 50% of the associated risk of stroke compared to ibuprofen, and was also associated with a reduced number of myocardial infarctions compared to control groups.[7] As with other non-COX-2 selective NSAIDs, naproxen can cause gastrointestinal problems, such as heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, ulcers and stomach bleeding.[9] Persons with a history of ulcers or inflammatory bowel disease should consult a doctor before taking naproxen.

A study found that high-dose naproxen induced near-complete suppression of platelet thromboxane throughout the dosing interval and appeared not to increase cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, whereas other high-dose NSAID regimens had only transient effects on platelet COX-1 and were associated with a small but definite vascular hazard. Conversely, naproxen was associated with higher rates of upper gastrointestinal bleeding complications compared to other NSAIDs.[8]

NSAID painkillers such as naproxen may interfere with and reduce the efficacy of SSRI antidepressants.[10]

Mechanism of action

Naproxen works by reversibly inhibiting both the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes.[11][12][13][14][15]

Compound information

Naproxen is a member of the 2-arylpropionic acid (profen) family of NSAIDs.[16] The free acid is an odorless, white to off-white crystalline substance. It is lipid-soluble and practically insoluble in water. It has a melting point of 152–155 °C.

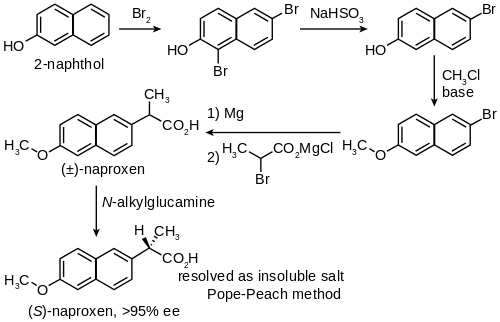

Synthesis

Naproxen has been industrially produced by Syntex as follows:[17]

Marketing and brand names

Naproxen and naproxen sodium are marketed under various brand names, including: Aleve, Accord, Anaprox, Antalgin, Apranax, Feminax Ultra, Flanax, Inza, Midol Extended Relief, Nalgesin, Naposin, Naprelan, Naprogesic, Naprosyn, Narocin, Pronaxen, Proxen, Soproxen, Synflex, MotriMax, and Xenobid. It is also available bundled with esomeprazole magnesium in delayed release tablets under the brand name Vimovo.[18]

Access restrictions

Syntex first marketed naproxen in 1976 as the prescription drug Naprosyn. They first marketed naproxen sodium under the brand name Anaprox in 1980. It remains a prescription-only drug in much of the world. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it as an over-the-counter (OTC) drug in 1994. OTC preparations in the U.S. are mainly marketed by Bayer HealthCare under the brand name Aleve and generic store brand formulations in 220 mg tablets. In Australia, packets of 275 mg tablets of naproxen sodium are Schedule 2 pharmacy medicines, with a maximum daily dose of five tablets or 1375 mg. In the United Kingdom, 250 mg tablets of naproxen were approved for OTC sale under the brand name Feminax Ultra in 2008, for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea in women aged 15 to 50.[19] In the Netherlands, 220 mg and 275 mg tablets are available OTC in drugstores, 550 mg is OTC only at pharmacies. Aleve became available over-the-counter in most provinces in Canada on 14 July 2009, but not British Columbia, Quebec or Newfoundland and Labrador;[20] it subsequently became available OTC in British Columbia in late January 2010.[21]

Research

Naproxen may have anti-viral activity against influenza. Specifically, it blocks the RNA-binding groove of the nucleoprotein of the virus, preventing formation of the ribonucleoprotein complex—thus taking the viral nucleoproteins out of circulation.[22]

Use in horses

Naproxen is given orally to horses at a dose of 10 mg/kg, and has shown to have a wide safety margin (no toxicity when given at 3-times the recommended dose of 42 days).[23] It is more effective for myositis than the commonly used NSAID phenylbutazone, and has shown especially good results for treatment of equine exertional rhabdomyolysis,[24] but is less commonly used for musculoskeletal disease.

References

- ↑ Gill, A, ed. (July 2013). STANDARD FOR THE UNIFORM SCHEDULING OF MEDICINES AND POISONS (PDF). The Poisons Standard 2013. Therapeutic Goods Administration. ISBN 978-1-74241-895-7.

- 1 2 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- 1 2 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ↑ Richy, F; Bruyere, O; Ethgen, O; Rabenda, V; Bouvenot, G; Audran, M; Herrero-Beaumont, G; Moore, A; Eliakim, R; Haim, M; Reginster, JY (July 2004). "Time dependent risk of gastrointestinal complications induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use: a consensus statement using a meta-analytic approach.". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 63 (7): 759–66. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.015925. PMC 1755051

. PMID 15194568.

. PMID 15194568. - ↑ French L (2005). "Dysmenorrhea" (PDF). Am Fam Physician. 71 (2): 285–91. PMID 15686299.

- ↑ Zell JA, Chang JC (November 2005). "Neoplastic fever: a neglected paraneoplastic syndrome". Support Care Cancer. 13 (11): 870–7. doi:10.1007/s00520-005-0825-4. PMID 15864658.

- 1 2 Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, Egger M, Jüni P (2011). "Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis". BMJ. 342: c7086. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7086. PMC 3019238

. PMID 21224324. c7086.

. PMID 21224324. c7086. - 1 2 Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, Abramson S, Arber N, Baron JA, Bombardier C, Cannon C, Farkouh ME, FitzGerald GA, Goss P, Halls H, Hawk E, Hawkey C, Hennekens C, Hochberg M, Holland LE, Kearney PM, Laine L, Lanas A, Lance P, Laupacis A, Oates J, Patrono C, Schnitzer TJ, Solomon S, Tugwell P, Wilson K, Wittes J, Baigent C (August 2013). "Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials". Lancet. 382 (9894): 769–79. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9. PMC 3778977

. PMID 23726390.

. PMID 23726390. - ↑ Naproxen. PubMed Health.

- ↑ Warner-Schmidt JL, Vanover KE, Chen EY, Marshall JJ, Greengard P (May 2011). "Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (22): 9262–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104836108. PMC 3107316

. PMID 21518864.

. PMID 21518864. - ↑ Duggan KC, Walters MJ, Musee J, Harp JM, Kiefer JR, Oates JA, Marnett LJ (November 2010). "Molecular basis for cyclooxygenase inhibition by the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen". J. Biol. Chem. 285 (45): 34950–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.162982. PMC 2966109

. PMID 20810665.

. PMID 20810665. - ↑ Hinz B, Cheremina O, Besz D, Zlotnick S, Brune K (April 2008). "Impact of naproxen sodium at over-the-counter doses on cyclooxygenase isoforms in human volunteers". Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 46 (4): 180–6. doi:10.5414/CPP46180. PMID 18397691.

- ↑ Van Hecken A, Schwartz JI, Depré M, De Lepeleire I, Dallob A, Tanaka W, Wynants K, Buntinx A, Arnout J, Wong PH, Ebel DL, Gertz BJ, De Schepper PJ (October 2000). "Comparative inhibitory activity of rofecoxib, meloxicam, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen on COX-2 versus COX-1 in healthy volunteers". J Clin Pharmacol. 40 (10): 1109–20. doi:10.1177/009127000004001005. PMID 11028250.

- ↑ Gross GJ, Moore J (July 2004). "Effect of COX-1/COX-2 inhibition versus selective COX-2 inhibition on coronary vasodilator responses to arachidonic acid and acetylcholine". Pharmacology. 71 (3): 135–42. doi:10.1159/000077447. PMID 15161995.

- ↑ Hawkey CJ (October 2001). "COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 15 (5): 801–20. doi:10.1053/bega.2001.0236. PMID 11566042.

- ↑ el Mouelhi M, Ruelius HW, Fenselau C, Dulik DM (1987). "Species-dependent enantioselective glucuronidation of three 2-arylpropionic acids. Naproxen, ibuprofen, and benoxaprofen". Drug Metab. Dispos. 15 (6): 767–72. PMID 2893700.

- ↑ Harrington PJ, Lodewijk E (1997). "Twenty Years of Naproxen Technology". Org. Process Res. Dev. 1 (1): 72–76. doi:10.1021/op960009e.

- ↑ "Vimovo's hotsite". vimovo.com. 11 March 2015.

- ↑ "Medicines regulator approves availability of a new OTC medicine for period pain" (PDF) (Press release). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 1 April 2008.

- ↑ "ALEVE – Welcome to Canada, Eh!" (PDF) (Press release). Bayer Health Care. 14 July 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ↑ "ALEVE® – Helping British Columbians with Joint and Arthritis Pain Get Back to Doing the Activities They Love". newswire.ca. 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Lejal N, Tarus B, Bouguyon E, Chenavas S, Bertho N, Delmas B, Ruigrok RW, Di Primo C, Slama-Schwok A (May 2013). "Structure-based discovery of the novel antiviral properties of naproxen against the nucleoprotein of influenza A virus". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 (5): 2231–42. doi:10.1128/AAC.02335-12. PMC 3632891

. PMID 23459490. Lay summary – EurekAlert!.

. PMID 23459490. Lay summary – EurekAlert!. - ↑ McIlwraith CW, Frisbie DD, Kawcak CE. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Proc. AAEP 2001 (47): 182-187.

- ↑ May SA, Lees P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In McIlwraith CW, Trotter GW, eds. Joint disease in the horse. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996;223–237.

External links

| Look up naproxen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- CID 1302 from PubChem

- EINECS number 244-838-7

- MedlinePlus Information on naproxen

- FDA Drug Prescribing Information on drugs.com

- FDA Statement on Naproxen, released 20 December 2004

- Alzheimer's Disease Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial

- Forbes article (expressing the point of view that the risk of heart attack or stroke was overstated)

- Which NSAID for Heart Disease Patients? – Medscape

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Naproxen

- Aleve Daily Med

- Naproxen bound to proteins in the PDB

- Use of naproxen in the Treatment of RSD