Nea Ekklesia

The Nea Ekklēsia (Greek: Νέα Ἐκκλησία, "New Church") was a church built by Byzantine Emperor Basil I the Macedonian in Constantinople between the years 876–80. It was the first monumental church built in the Byzantine capital after the Hagia Sophia in the 6th century, and marks the beginning of the middle period of Byzantine architecture. It continued in use until the Palaiologan period. Used as a gunpowder magazine by the Ottomans, the building was destroyed in 1490 after being struck by lightning. In English usage, the church is usually referred to as The Nea.

History

Emperor Basil I was the founder of the Macedonian dynasty, the most successful in Byzantine history. Basil regarded himself as a restorer of the empire, a new Justinian, and initiated a great building program in Constantinople in emulation his great predecessor. The Nea was to be Basil’s Hagia Sophia, with its very name, "New Church", implying the beginning of a new era.[1]

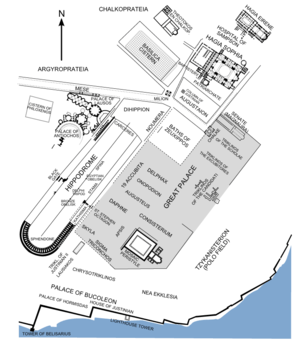

The church was built under the personal supervision of Basil,[2][3] in the southeastern corner of the Great Palace complex,[4] near the location of the earlier tzykanistērion (polo field). Basil built another church nearby, the "Theotokos of the Pharos". The Nea was consecrated on 1 May 880 by Patriarch Photius, and dedicated to Jesus Christ, the archangel Michael (in later sources, Gabriel), the Prophet Elijah (one of Basil’s favorite saints), the Virgin Mary and St Nicholas.[2][5]

It is indicative of Basil's intentions for this church that he endowed it with its own administration and estates, on the model of the Hagia Sophia. During his and his immediate successors’ reign, the Nea played an important role in palace ceremonies,[6] and at least until the reign of Constantine VII, the anniversary of its consecration was a major dynastic feast.[7] At some point in the late 11th century it was turned into a monastery, and was known as the "New Monastery" (Νέα Μονή).[4] Emperor Isaac II Angelos stripped it of much of its decoration, its furniture and liturgical vessels,[8] and used them to restore the church of St Michael at Anaplous.[9] The building continued to be used by the Latins and survived the Palaiologan period until after the Ottoman conquest of the city. The Ottomans however used it for gunpowder storage. Thus in 1490, when the building was struck by a lightning, it was destroyed and subsequently torn down.[4] As a result, the only information we have about the church comes from literary evidence, especially the mid-10th century Vita Basilii, as well a few crude depictions in maps.[1]

Description

As noted, not much is known about the details of the structure. The church was built with five domes: the central dome was dedicated to Christ while the four smaller ones housed chapels of the four other saints to whom the church was dedicated. The exact arrangement of the domes and the type of the church are disputed.[10] Most scholars consider it to have been a cross-in-square structure,[11] similar to the later Myrelaion and Lips Monastery churches. Indeed, the widespread use of this type throughout the Orthodox world, from the Balkans to Russia, is commonly ascribed to the prestige of this imperial building.[12]

The church was the crowning achievement of Basil's building program, and he spared no expense to decorate it as lavishly as possible: other churches and structures in the capital, including the mausoleum of Justinian, were stripped,[12] and the Imperial fleet employed with transporting marble for its construction, with the result that Syracuse, the main Byzantine stronghold in Sicily, was left unsupported and fell to the Arabs.[13]

Basil's grandson, the Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, gives the following description of the church's decoration in a laudatory ekphrasis:[14]

This church, like a bride adorned with pearls and gold, with gleaming silver, with a variety of many-hued marble, with compositions of mosaic tesserae, and clothing of silken stuffs, he [Basil] offered to Christ, the immortal Bridegroom. Its roof, consisting of five domes, gleams with gold and is resplendent with beautiful images as with stars, while on the outside it is adorned with brass that resembles gold. The walls on either side are beautified with costly marbles of many hues, while the sanctuary is enriched with gold and silver, precious stones, and pearls. The barrier that separates the sanctuary from the nave, including the columns that pertain to it and the lintel that is above them; the seats that are within, and the steps that are in front of them, and the holy tables themselves — all of these are of silver suffused with gold, of precious stones and costly pearls. As for the pavement, it appears to be covered in silken stuffs of Sidonian workmanship; to such an extent has it been adorned all over with marble slabs of different colors enclosed by tessellated bands of varied aspect, all accurately joined together and abounding in elegance.

The atrium of the church lay before its western entrance, and was decorated with two fountains of marble and porphyry. Two porticoes ran along the northern and southern sides of the church up to the tzykanistērion, and on the seaward (southern) side, a treasury and a sacristy were built. To the east of the church complex lay a garden, known as mesokēpion ("middle garden").[15]

Relics

Along with the oratory of St Stephen in the Daphne Palace and the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos, the Nea was the chief repository of holy relics in the imperial palace.[16] These included the sheepskin cloak of the prophet Elijah, the table of Abraham, at which he hosted three angels, the horn which the prophet Samuel had used to anoint David, and relics of Constantine the Great. After the 10th century, further relics were apparently moved there from other locations in the palace, including the "rod of Moses" from the Chrysotriklinos.[17]

See also

References

- 1 2 Stankovic (2008)

- 1 2 Mango (1986), p. 194

- ↑ Magdalino (1987), p. 51

- 1 2 3 Mango (1991), p. 1446

- ↑ Ousterhout (2007), p. 34

- ↑ Magdalino (1987), pp. 61–3

- ↑ Magdalino (1987), p. 55

- ↑ Mango (1986), p. 237

- ↑ Ousterhout (2007), p. 140

- ↑ Ousterhout (2007), p. 36

- ↑ Mango (1976), p. 196

- 1 2 Mango (1986), p. 181

- ↑ Treadgold (1995), p. 33

- ↑ Ousterhout (2007), pp. 34–35

- ↑ Mango (1986), pp. 194–196

- ↑ Klein (2006), p. 93

- ↑ Klein (2006), pp. 92–93

Sources

- Magdalino, Paul (1987). "Observations on the Nea Ekklesia of Basil I". Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik (37): 51–64. ISSN 0378-8660.

- Mango, Cyril (1976). Byzantine architecture. New York. ISBN 0-8109-1004-7.

- Mango, Cyril (1986). The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453: Sources and Documents. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6627-5.

- Mango, Cyril (1991). "Nea Ekklesia". In Kazhdan, Alexander. Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. p. 1446. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Klein, Holger A. (2006). Bauer, F.A., ed. "Sacred Relics and Imperial Ceremonies at the Great Palace of Constantinople" (PDF). BYZAS (5): 79–99.

- Ousterhout, Robert (1998). "Reconstructing ninth-century Constantinople". In L. Brubaker. Byzantium in the ninth century: dead or alive? Papers from the thirtieth spring symposium of Byzantine studies, Birmingham, March 1996. Aldershot. pp. 115–30.

- Ousterhout, Robert (2007). Master Builders of Byzantium. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology. ISBN 978-1-934536-03-2.

- Stankovic, Nebojsa (2008-03-21). "Nea Ekklesia". Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World, Constantinople. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1995). Byzantium and Its Army, 284–1081. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3163-2.

External links