Neostigmine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Prostigmin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| ATC code | N07AA01 (WHO) S01EB06 (WHO) QA03AB93 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Unclear, probably less than 5% |

| Metabolism | Slow hydrolysis by acetylcholinesterase and also by plasma esterases |

| Biological half-life | 50–90 minutes |

| Excretion | Unchanged drug (up to 70%) and alcoholic metabolite (30%) are excreted in the urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

59-99-4 |

| PubChem (CID) | 4456 |

| DrugBank |

DB01400 |

| ChemSpider |

4301 |

| UNII |

3982TWQ96G |

| KEGG |

D08261 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:7514 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL54126 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

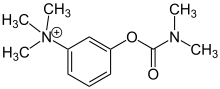

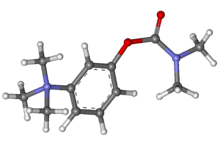

| Formula | C12H19N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 223.294 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Neostigmine (Prostigmin, Vagostigmin) (from Greek neos, meaning "new," and "-stigmine," in reference to its parent molecule, physostigmine, on which it is based[1]) is a parasympathomimetic compound that acts as a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. Given that it is a quaternary amine (unlike physostigmine, which is a tertiary amine), it penetrates the central nervous system poorly and has lower propensity to cause side effects there.

It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[2]

Medical uses

It is used to improve muscle tone in people with myasthenia gravis, and also to reverse the effects of non-depolarizing muscle relaxants such as rocuronium and vecuronium at the end of an operation, usually in a dose of 25 to 50 μg per kilogram.

Another indication for use is the conservative management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie's syndrome, in which patients get massive colonic dilatation in the absence of a true mechanical obstruction.[3]

Hospitals sometimes administer a solution containing neostigmine intravenously to delay the effects of envenomation through snakebite.[4] Some promising research results have also been reported for administering the drug nasally as a snakebite treatment.[5]

Side effects

Neostigmine can induce generic ocular side effects including: headache, brow pain, blurred vision, phacodonesis, pericorneal injection, congestive iritis, various allergic reactions, and rarely, retinal detachment.[6]

Neostigmine will cause slowing of the heart rate (bradycardia); for this reason it is usually given along with a parasympatholytic drug such as atropine or glycopyrrolate.

Gastrointestinal symptoms occur earliest after ingestion and include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea.[7]

Pharmacology

By interfering with the breakdown of acetylcholine, neostigmine indirectly stimulates both nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. Unlike physostigmine, neostigmine has a quaternary nitrogen; hence, it is more polar and does not enter the CNS, but it does cross the placenta. Its effect on skeletal muscle is greater than that of physostigmine. Neostigmine has moderate duration of action – usually two to four hours.[8] Neostigmine binds to the anionic and esteric site of cholinesterase. The drug blocks the active site of acetylcholinesterase so the enzyme can no longer break down the acetylcholine molecules before they reach the postsynaptic membrane receptors. This allows for the threshold to be reached so a new impulse can be triggered in the next neuron. In myasthenia gravis there are too few acetylcholine receptors so with the acetylcholinesterase blocked, acetylcholine can bind to the few receptors and trigger a muscular contraction.

Spectral data

Neostigmine shows notable UV/VIS absorption at 261 nm, 267 nm, and 225 nm.[9]

Neostigmine's 1H NMR Spectroscopy reveals shifts at: 7.8, 7.7, 7.4, 7.4, 3.8, and 3.1 parts per million. The higher shifts are due to the aromatic hydrogens. The lower shifts at 3.8ppm and 3.1ppm are due to the electronic withdrawing nature of the tertiary and quarterary nitrogen, respectively.[10]

Chemistry

Neostigmine, N,N,N-trimethyl-meta-(dimethylcarbomoyloxy)-phenylammonium methylsulfonate, which can be viewed as a simplified analog of physostigmine, is made by reacting 3-dimethylaminophenol with N-dimethylcarbamoyl chloride, which forms the dimethylcarbamate, and its subsequent alkylation using dimethylsulfate forming the desired compound.

History

Neostigmine was first synthesized by Aeschlimann and Reinert in 1931[11] and was patented by Aeschliman in 1933.[12]

Neostigmine is made by first reacting 3-dimethylaminophenol with N-dimethylcarbamoyl chloride, which forms a dimethylcarbamate. Next, that product is alkylated using dimethylsulfate, which forms neostigmine.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ "neostigmine: definition of neostigmine in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Maloney, Nell; Vargas, H. David (2005-05-01). "Acute Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction (Ogilvie's Syndrome)". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 18 (02): 96–101. doi:10.1055/s-2005-870890. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 2780141

. PMID 20011348.

. PMID 20011348. - ↑ Franklin, Deborah, "Potential Treatment For Snakebites Leads To A Paralyzing Test", NPR.org, July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Universal antidote for snakebite: Experimental trial represents promising step", California Academy of Sciences via Science Daily, May 28, 2014.

- ↑ Gilman, Goodman & Gilman 1980, p. 114.

- ↑ Gilman, Goodman & Gilman 1980, p. 109.

- ↑ Howland, R. D., Mycek, M. J., Harvey, R. A., Champe, P. C., and Mycek, M. J., Pharmacology 3rd edition, Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews, 2008, pg. 51.

- ↑ Porst H; Kny L (May 1985). "The structure of degradation products of neostigmine bromide". Die Pharmazie (in German). 40 (5): 325–8. PMID 4034636.

- ↑ Ferdous, Abu J; Waigh, Roger D (1993). "Application of the WATR technique for water suppression in 1H NMR spectroscopy in determination of the kinetics of hydrolysis of neostigmine bromide in aqueous solution". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 45 (6): 559–562. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1993.tb05598.x. PMID 8103105.

- ↑ Whitacre 2007, p. 57.

- ↑ Aeschliman, John A., U.S. Patent 1,905,990 (1933).

- ↑ Gilman, Goodman & Gilman 1980, p. 103.

Bibliography

- Gilman, A.G.; Goodman, L.S.; Gilman, A. (1980). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (6th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

- Whitacre, David M. (2007). Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-387-73162-9.