New Belgrade

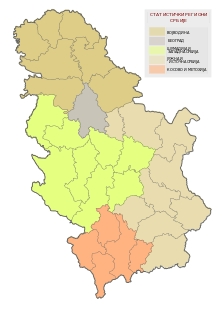

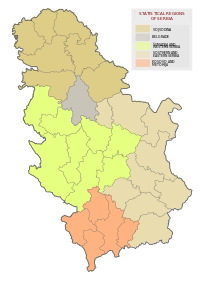

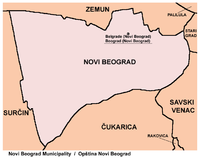

| New Belgrade Нови Београд / Novi Beograd | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

|

New Belgrade by night | |||

| |||

Location of Novi Beograd in Belgrade | |||

| Country | Serbia | ||

| City | Belgrade | ||

| Status | Municipality | ||

| Settlements | 1 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Municipality of Belgrade | ||

| • Mun. president | Aleksandar Šapić (independent) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 40.74 km2 (15.73 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2011) | |||

| • Total | 212,104 | ||

| • Density | 5,200/km2 (13,000/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 11070 | ||

| Area code(s) | +381 11 | ||

| Car plates | BG | ||

| Website | www.novibeograd.rs | ||

New Belgrade (Serbian: Нови Београд / Novi Beograd, pronounced [nôʋiː beǒɡrad]) is one of 17 city municipalities that constitute the City of Belgrade, capital of Serbia. It is a planned city, built since 1948 in a previously uninhabited area on the left bank of the Sava River, opposite the old Belgrade. In recent years it has become the central business district of Belgrade and its fastest developing area, with many businesses moving to the new part of the city, due to more modern infrastructure and larger available space. With 212,104 inhabitants,[1] it is the second most populous municipality of Serbia after Novi Sad.

History

Early history

The first record of human settlement on the territory of today's New Belgrade dates back to Ottoman rule. The book Kruševski pomenik, published in 1713, notes the existence of a Serb village called Bežanija as early as 1512. It also mentions the village had 32 houses, a number that grew to 115 by the year 1810.

Between two world wars of the 20th century, communities sprung up closer to Sava River in Staro Sajmište and Novo Naselje.

The first urbanization plans that talk about Belgrade's expansion to the Sava's left bank were drawn up in 1923, but a lack of either funds or the manpower needed to drain out the swampy terrain put them on hold indefinitely. In 1924 Petar Kokotović opened a kafana on Tošin Bunar with the prophetic name Novi Beograd. After 1945 Kokotović was president of the local community of Novo Naselje–Bežanija which later grew into the municipality of Novi Beograd.[2] In 1924 an airport was built in Bežanija and in 1928 the Rogožerski factory was constructed. In 1934 plans were expanded to include the creation of a new urban tissue which connected Belgrade and Zemun, as Zemun was administratively annexed to the city of Belgrade in 1929, losing separate city status in 1934. A bridge was also built over the Sava River and a tram line connecting Belgrade and Zemun was established. Also, a Zemun airport was built.

In 1938, a complex of buildings in the community of Staro Sajmište went up. Spread over 15 thousand square metres it hosted fairs and exhibitions designed to show off the Kingdom of Yugoslavia's developing economy. Also this year, the municipality of Belgrade signed a contract with two Danish construction companies, Kampsax and Højgaard & Schultz, to build the new neighbourhood. Engineer Branislav Nešić was entrusted with leading the project. He even continued his involvement on the project after 1941 when the Nazis conquered, occupied, and dismembered the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Because of this, the new communist authorities who came to power after 1945 put Nešić on trial as a collaborator.

Sajmište concentration camp

In 1941, German forces occupied much of the Kingdom. Nazi secret police, Gestapo, took over the fairgrounds (Sajmište). They encircled it with several rings of barbed wire turning it into a "collection centre". It eventually became an extermination camp. Until May 1942 it was mostly used to kill off Jews from Belgrade and other parts of Serbia, and from April 1942 onwards, it also held political prisoners. Executions of captured prisoners lasted as long as the camp existed. November 1946 report released by the Yugoslav State Commission for Crimes of Occupiers and their Collaborators claims that close to 100,000 prisoners came through the Sajmište's gates. It is estimated that around 48,000 people perished inside the camp.

Rapid development

It was on April 11, 1948, three years after World War II ended, that the ground was broken on a huge construction project, which would give birth to what is known today as New Belgrade.

Buildings sprung up one after another and by 1952, New Belgrade was officially a municipality. In 1955 the municipality of Bežanija was annexed to New Belgrade. It was for years the biggest construction site in Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia and a huge source of pride for country's communist authorities that oversaw the project.

During first three years of construction alone, over 100 thousand workers and engineers from all over the freshly liberated country took part in the building process. Work brigades made up of villagers brought in from rural Serbia provided most of the manual labour. Even high school and university student volunteers took part. It was backbreaking labour that went on day and night. With no notable technological tools to speak of, mixing of concrete and spreading of sand were done by hand with horse carriages only used for extremely heavy lifting.

Before the actual construction started, the terrain was evenly covered with sand from the Sava and the Danube rivers in an effort to dry out the land and raise it above the reach of flooding and underground streams.

Among the first to go up was the SIV 1 building, which housed the Federal Executive Council (SIV). The building has 75,000 square metres of usable space. Built during the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, it was also used during the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia before its dissolution. The building was renamed to Palata Srbije, and now houses some departments of the Serbian government.

First buildings for classic residential purposes were built as pavilions close to the area known as Tošin Bunar (Toša's Well). Studentski Grad (Student City) complex was also built around the same time to meet the residence needs of the growing University of Belgrade student body that came from other parts of Yugoslavia.

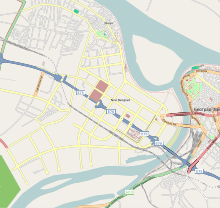

Geography

New Belgrade is located on the left bank of the Sava River, in the easternmost part of the Srem region. Administratively, its northeastern section touches the right bank of the Danube, right before the Sava's confluence. It is generally located west of the 'Old' Belgrade to which it is connected by six bridges (Gazela, Branko's bridge, Old Railway Bridge (Belgrade), New Railway Bridge and Ada Bridge). European route E75, with five grade separations, including a new double-looped one at the Belgrade Arena, goes right through the middle of the settlement.

The municipality of New Belgrade covers an area of 40.74 square kilometres (15.73 sq mi). Its terrain is flat, which poses a high contrast to the old Belgrade, built on 32 hills total. Except for its western section, Bežanija, New Belgrade is built on a terrain that was essentially a swamp when construction of the new city began in 1948. For years, kilometers-long conveyor belts were transporting sand from the Danube's island of Malo Ratno Ostrvo, almost completely destroying it in the process, and only a small, narrow strip of wooded land remains today. Thus, it is romantically said that New Belgrade is actually built on an island.

Other geographic features are the peninsula of Mala Ciganlija and the island of Ada Međica, both on the Sava and the bay of Zimovnik (winter shelter), engulfed by Mala Ciganlija, with the facilities of the Beograd shipyard. The loess slope of Bežanijska Kosa is located in the western part of the municipality, while in the southern, the Galovica river canal flows into the Sava.

Though it has no forests in the real sense, of all urban municipalities of Belgrade, Novi Beograd has the largest green areas, with a total of 3.47 square kilometres (1.34 sq mi), or 8.5% of the territory.[3] Majority of these are made up of the large Ušće park. The latest addition to Belgrade parks, Park Republika Srpska from 2008, is also located in the municipality.

There are no separate settlements within the municipality, as the entire area administratively belongs to the Belgrade City proper and is statistically classified as part of Belgrade (Beograd-deo). The area located around the municipal assembly building and the nearby roundabout is considered to be New Belgrade's center.

As it was planned and constructed, New Belgrade was divided into blocks. Currently, there are 72 blocks (with several sub-blocks, like 70-a, etc.). Old core of the village of Bežanija, Ada Međica, and Mala Ciganlija, as well as the area along the highway west of Bežanijska Kosa are not divided into blocks, while due to the administrative borders changes, some of the blocks (9, 9-a, 9-b, 11, 11-c and 50) belong to the municipality of Zemun, extending north of New Belgrade as one continuous built-up area.

Economy

As all of the socialist governments considered heavy industry to be the driving force of the entire economy, it for decades dominated New Belgrade's economy too: Motors and Tractors Industry - IMT, Metallic cast iron factory - FOM, Beograd (formerly Tito) shipyard, large heating plant in Savski Nasip, MINEL electro-construction company, etc. All of these complexes will be removed and develop in business and residential areas.

In the 1990s with the collapse of gigantic state-owned companies, New Belgrade's local economy bounced back by switching to commercial facilities, with dozens of shopping malls and entire commercial sections such as Mercator Center Belgrade, Ušće Mall, Delta City Belgrade etc. These activities are further enhanced in the 2000s (decade). The 'Open Shopping Mall' or the Belgrade's flea market is also located in New Belgrade.

New Belgrade became the main business district in Serbia and one of major in Southeast Europe. Many companies choose New Belgrade for regional centres such as Ikea, Energoprojekt holding, Delta Holding, DHL, Air Serbia, OMV, Siemens, Société Générale, Telekom Srbija, Telenor Serbia, Unilever, Vip mobile, Yugoimport SDPR, Ericsson, Colliers International, CB Richard Ellis, SNC-Lavalin, Hewlett-Packard, Huawei, Ernst & Young and Arabtec.[4] The Belgrade Stock Exchange is also located in New Belgrade. Other notable structures built not too long afterwards include convention and congress hall Sava Center, Hotel Jugoslavija, Genex condominium, Genex Tower sports and concert venues Hala Sportova and Belgrade Arena, and 4 and 5-star hotels Crowne Plaza Belgrade, Holiday Inn, Hyatt Regency, Tulip Inn etc., with around 1700 rooms,... Many structures are currently under construction like Airport City Belgrade, Elektroprivreda Srbije HQ., West 65 business-residential complex, etc.

Many IT companies choose New Belgrade as regional center like Cisco Systems, SAP AG, Acer, Comtrade group, Imtel Computers, Hewlett-Packard, Huawei, Samsung. One of Microsoft's development centers is also located in New Belgrade.

Currently finished projects in New Belgrade are Delta City, Sava City, Univerzitetsko Selo, Ada Bridge, Intesa HQ and Ušće Tower.

Demographics

Ever since the construction began in 1948, New Belgrade experienced explosive population growth, but oddly, as the 2002 census showed, the population size actually decreased slightly during the 1990s.

Historical population of New Belgrade:

| Census year | Total population |

|---|---|

| 1953 | 11,339 |

| 1961 | 33,347 |

| 1971 | 92,500 |

| 1981 | 173,541 |

| 1991 | 218,633 |

| 2002 | 217,773 |

| 2011 | 212,104 |

According to the 2002 census, the major ethnic groups in the municipality were:

| Ethnic Origin | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 187,253 | 85.98 |

| Yugoslavs | 5,341 | 2.45 |

| Montenegrins | 5,233 | 2.40 |

| Croats | 2,520 | 1.16 |

| Romani | 2,371 | 1.09 |

| Macedonians | 1,683 | 0.77 |

| Others | 13,372 | 6.14 |

Neighbourhoods

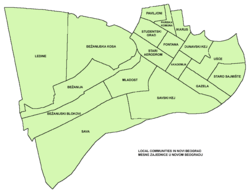

Just like other municipalities of Serbia, New Belgrade is further divided into local communities (Serbian: mesna zajednica). Apart from Bežanija and Staro Sajmište, no other neighbourhoods have historical or traditional names, as Novi Beograd did not exist as such. However, in the five decades of its existence, some of its parts gradually became known as distinct neighborhoods of their own.

List of the neighbourhoods of New Belgrade:

Politics

Historical Presidents of the Municipal Assembly since 1952:[5]

- 1952 - 1953: Stevan Galogaža

- 1953 - 1955: Mile Vukmirović

- 1955 - 1956: Živko Vladisavljević

- 1956 - 1957: Ilija Radenko

- 1957 - 1962: Ljubinko Pantelić

- 1962 - 1965: Jova Marić

- 1965 - 1969: Pero Kovačević (born 1923)

- 1969 - April 11, 1979: Novica Blagojević (died 1979)

- 1979 - 1982: Milan Komnenić

- 1982 - 1986: Andreja Tejić

- 1986 - 1989: Toma Marković

- 1989 - October 12, 2000: Čedomir Ždrnja (born 1936)

- October 12, 2000 - July 11, 2008: Željko Ožegović (born 1962)

- July 11, 2008 – June 27, 2012: Nenad Milenković (born 1972)

- June 27, 2012 – present: Aleksandar Šapić (born 1978)

Culture and education

For a settlement of such size, New Belgrade has some unusual cultural characteristics, influenced by the Yugoslav communists' ideas how a new and modern city should look like. If it can be understood why there were no churches built, a fact that a city of 250,000 has no theaters and only one museum (out of the residential area) is much less comprehensible, underlying the decades long Belgrader's feel of New Belgrade being nothing more but a big dormitory.

Museum of Contemporary Art is located in Ušće which is also projected by the city government as the location of the future Belgrade Opera. The issue became highly controversial in the 2000s (decade) as the general feel of the population, ensemble of the opera and most prominent architects and artists is that it is a very bad location for the opera, while the city government stubbornly insists against the popular wishes.

For decades, the only church in the municipality was an old Church of Saint George in Bežanija. Construction of the new church in Bežanijska Kosa, the Church of Saint Basil of Ostrog, began in 1996, while the construction of the Church of Saint Demetrius of Salonica, which is considered the first church in New Belgrade, began in 1998. Both are still not completed.

Schools

Education fared much better than culture, as there are numerous elementary and high schools, as well as University of Belgrade's residential campus - Studentski Grad.

List of schools in New Belgrade:

- Ninth Belgrade Gymnasium

- Tenth Belgrade Gymnasium

- University of Arts' Faculty of Dramatic Arts (FDU)

- Megatrend University

- Graphic Design Secondary School

- Polytechnical Academy

- Technical School

- Russian School

Night life

New Belgrade offers rich night life along the banks of Sava and Danube, right up to the point where the two rivers meet. What started mostly as raft-like social clubs for river fishermen in the 1980s expanded into large floats offering food and drink with live turbo folk performances during the 1990s.

Today, it is unlikely that one would walk a 100-metre (330-foot) stretch along the rivers without encountering a float. Some of them grew into entire entertainment complexes rivaling clubs in Belgrade's downtown core. While most of the floats used to be synonymous with turbo folk in what was essentially a stereotypical kafana setting, a recent trend saw many turned into full-fledged clubs on water with elaborate events involving world-famous DJs spinning live music.

Criticism and public image

Not much attention was paid to detail and subtlety when New Belgrade was being built during the late 1940s and early 1950s. The objective was clearly to put up as many buildings, as fast as possible, in order to accommodate a displaced and growing post World War II population that was in the middle of a baby boom.

This across-the-board brutalist architectural approach led to many apartment buildings and even entire residential blocks looking monumental in an awkward way. Although the problem has been alleviated to certain extent in recent decades by addition of some modern expansion (Hyatt and Intercontinental hotels, luxury Genex condos, Ušće Tower, Belgrade Arena, Delta City, etc.), many still complain about what they see as New Belgrade's "grayness" and "drabness". They often use the derisive term "spavaonica" ("dormitory") to underscore their view of New Belgrade as a place that does not inspire creative living nor encourage healthy human interaction, and is only good for overnight sleep at the end of the hard day's work.

This opinion has found its way into Serbian pop culture as well.

In an early 1980s track called 'Neću da živim u Bloku 65', popular Serbian band Riblja čorba sings about a depressed individual who hates the world because he's surrounded by the concrete of New Belgrade, while a more recent local cinematic trend sees New Belgrade presented somewhat clumsily as the Serbian version of New York ghettos like those found in Harlem, Brooklyn and The Bronx. The most obvious example of the latter would be 2002 movie 1 na 1, which portrays a bunch of Serbian teenagers who rap, shoot guns, play street basketball and seem to blame many of their woes on living in New Belgrade. Other films like Apsolutnih 100 and The Wounds also implicitly paint New Belgrade in the negative light but they have a more coherent point of view and place their stories within the context of the 1990s when war and international isolation truly did push some Serbs, including those inhabiting New Belgrade, to desperate acts.

Twin towns – Sister cities

New Belgrade is twinned with the following cities and municipalities:[6]

Belfort, France

Belfort, France Karpoš, Republic of Macedonia

Karpoš, Republic of Macedonia Xanthi, Greece

Xanthi, Greece Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Notable people

- Aleksandar Vučić, politician

- Zoran Đinđić, politician

- Nemanja Bjelica, basketballer

- Aleksandar Šapić, politician, former waterpoloist

- Branka Katić, actress

See also

- Belgrade

- List of cities in Serbia

- Subdivisions of Belgrade

- List of Belgrade neighbourhoods and suburbs

References

Bibliography

- Mala Prosvetina Enciklopedija, Third edition (1986), Vol.I; Prosveta; ISBN 86-07-00001-2

- Jovan Đ. Marković (1990): Enciklopedijski geografski leksikon Jugoslavije; Svjetlost-Sarajevo; ISBN 86-01-02651-6

- Slobodan Ristanović (2008) : 60 godina Novog Beograda;

Notes

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Tab-2_10112011.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Bitka za Beograd", Politika (in Serbian), p. 11, 2008-04-11

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (26 April 2008). "Srpska prestonica u brojkama" (in Serbian). Politika. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ "Iz Beograda osvajaju Balkan" (in Serbian). Večernje novosti. 25 January 2014.

- ↑ http://www.danas.rs/danasrs/srbija/beograd/od_mocvare_do_poslovnog_centra.39.html?news_id=259028

- ↑ "Međunarodna saradnja" (in Serbian). novibeograd.rs.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Novi Beograd. |

Coordinates: 44°48′N 20°25′E / 44.800°N 20.417°E

.jpeg)