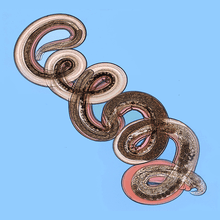

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis

| Nippostrongylus brasiliensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Chromadorea |

| Order: | Rhabditida |

| Suborder: | Strongylida |

| Superfamily: | Trichostrongyloidea |

| Family: | Heligmonellidae |

| Subfamily: | Nippostrongylinae |

| Genus: | Nippostrongylus |

| Species: | N. brasiliensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Nippostrongylus brasiliensis | |

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis is a gastrointestinal roundworm or nematode that infects rodents, primarily rats. This worm is a widely studied parasite due to its simple life-cycle and its ability to be used in animal models. It has a life-cycle similar to the human hookworms Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale which includes five molting stages to become sexually mature.

Life cycle

The life cycle is similar to that of the human hookworms, Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale.

Eggs located within the soil release motile, free-living worms that must molt twice (L1 and L2) in order to develop into their infective L3 stage. This L3 stage can penetrate through intact skin in as little as 4 hours. Once inside the host, the worms invade the venous circulation and are carried into the lungs, where they become trapped in the capillaries. When the worms mature into the L4 stage they rupture the capillaries and are released into the alveoli where they are coughed up and swallowed. They then reach the small intestines 3–4 days after the initial infection. The worms become adults after the final molt into the L5 stage where they begin laying eggs on the 6th day of infection.[1] The eggs are passed out of the host through feces and the cycle starts all over again.

N. brasiliensis are adapted to infecting rats and so can continue laying eggs for prolonged periods of time. The immune response of mice however, leads to cessation of egg laying by day 8 and adults are expelled by day 10.[2]

Animal model

N. brasiliensis provides a very valuable lab model in determining the migration pathway through the host. The life-cycle of N. brasiliensis can be passed through lab mice and due to this parasite is invaluable when it comes to being able to test for a variety of things. The availability of inbred and mutant mouse strains can be advantageous when examining the genetic basis of murine susceptibility and resistance to infection.[3] Animal models of N. brasiliensis infections can lead to a better understanding of the basic biology of the immune response and protective immunity. For instance, they can provide the model for induction and maintenance of Th2 type immune responses and exhibit all the characteristics for eosinophilia, mastocytosis, mucus production and CD4 T cell-dependent IgE production.[4]

Symptoms and diseases

Studies performed on lab mice revealed that mice previously infected with N. brasiliensis had developed massive emphysema with dilation of distal airspaces due to the loss of alveolar septa. The study shows that a N. brasiliensis infection can result in deterioration of the lung, destruction to the alveoli and long-term airway hyperresponsiveness which is consistent with emphysema and Chronic Obstructive Pulminary Disorder (COPD). This infection can lead to a chronic low level hemorrhaging of the lung. The damage to the lung tissue can result in the development of COPD and emphysema.[5] Among respiratory problems, a N. brasiliensis infection can also result in the loss of both body mass and red blood cell (RBC) density. Biphasic anorexia is also prevalent in laboratory rats infected with this parasite. The first phase coincides with the parasites invasion of the lung and the second phase occurs when the parasite matures inside the intestine.[6]

Treatment

Tetramisole loaded into zeolite is more effective at killing adult N. brasiliensis in rats than tetramisole alone.[7]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Locksley, Richard M., and Miranda Robertson. "11.4." Immunity: The Immune Response in Infectious and Inflammatory Disease. By Anthony L. DeFranco. N.p.: New Science, 2007. 274-75. Print.

- ↑ Locksley, Richard M., and Miranda Robertson. "11.4." Immunity: The Immune Response in Infectious and Inflammatory Disease. By Anthony L. DeFranco. N.p.: New Science, 2007. 274-75. Print.

- ↑ Stadnyk, A.W., P.J. McElroy, J. Gauldie, and A.D. Befus. 1990. Characterization of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection in different strains of mice. The Journal of Parasitology 76:377-382.

- ↑ Camberis, M., G. Le Gros, and J. Urban Jr. 2003. Animal model of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Heligmosmoides polygyrus. Current Protocols in Immunology Chapter 19.

- ↑ Marsland, B.J., M. Kurrer, R. Reissmann, N.L. Harris, and M. Kopf. 2008. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection leads to the development of emphysema associated with the induction of alternatively activated macrophages. European Journal of Immunology 38:479-488.

- ↑ Mercer, J.G., P.I. Mitchell, K.M. Moar, A. Bissett, S. Geissler, K. Bruce, and L.H. Chappell. 2000. Anorexia in rats infected with the nematode, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis: experimental manipulations. Parasitology 120:641-647.

- ↑ Shaker, S.K., A. Dyer, and D.M. Storey. 1992. Treatment of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in normal and SPF rats using tetramisole loaded with zeolite. Journal of Helminthology 66:288-292.