Dinitrogen tetroxide

| |||

Nitrogen dioxide at −196 °C, 0 °C, 23 °C, 35 °C, and 50 °C. (NO 2) converts to the colorless dinitrogen tetroxide (N 2O 4) at low temperatures, and reverts to NO 2 at higher temperatures. | |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Dinitrogen tetroxide | |||

| Other names

Dinitrogen(II) oxide(-I) | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 10544-72-6 | |||

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image | ||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:29803 | ||

| ChemSpider | 23681 | ||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.012 | ||

| EC Number | 234-126-4 | ||

| PubChem | 25352 | ||

| RTECS number | QW9800000 | ||

| UNII | M9APC3P75A | ||

| UN number | 1067 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| N2O4 | |||

| Molar mass | 92.011 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Colourless liquid/Orange gas | ||

| Density | 1.44246 g/cm3 (liquid, 21 °C) | ||

| Melting point | −11.2 °C (11.8 °F; 261.9 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 21.69 °C (71.04 °F; 294.84 K) | ||

| reacts | |||

| Vapor pressure | 96 kPa (20 °C)[1] | ||

| Refractive index (nD) |

1.00112 | ||

| Structure | |||

| planar, D2h | |||

| zero | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

| Std molar entropy (S |

304.29 J K−1 mol−1[2] | ||

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

+9.16 kJ/mol[2] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS | ||

| EU classification (DSD) |

| ||

| R-phrases | R26, R34 | ||

| S-phrases | (S1/2), S9, S26, S28, S36/37/39, S45 | ||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Nitrous oxide Nitric oxide Dinitrogen trioxide Nitrogen dioxide Dinitrogen pentoxide | |||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Dinitrogen tetroxide, commonly referred to as nitrogen tetroxide, is the chemical compound N2O4. It is a useful reagent in chemical synthesis. It forms an equilibrium mixture with nitrogen dioxide.

Dinitrogen tetroxide is a powerful oxidizer that is hypergolic (spontaneously reacts) upon contact with various forms of hydrazine, which makes the pair a popular bipropellant for rockets.

Structure and properties

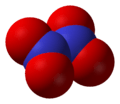

Dinitrogen tetroxide could be regarded as two nitro groups (-NO2) bonded together. It forms an equilibrium mixture with nitrogen dioxide.[3] The molecule is planar with an N-N bond distance of 1.78 Å and N-O distances of 1.19 Å. The N-N distance corresponds to a weak bond, since it is significantly longer than the average N-N single bond length of 1.45 Å.[4]

Unlike NO2, N2O4 is diamagnetic since it has no unpaired electrons.[5] The liquid is also colorless but can appear as a brownish yellow liquid due to the presence of NO2 according to the following equilibrium:

- N2O4 ⇌ 2 NO2

Higher temperatures push the equilibrium towards nitrogen dioxide. Inevitably, some dinitrogen tetroxide is a component of smog containing nitrogen dioxide.

Production

Nitrogen tetroxide is made by the catalytic oxidation of ammonia: steam is used as a diluent to reduce the combustion temperature. In the first step, the ammonia is oxidized into nitric oxide:

- 4NH3 + 5O2 → 4NO + 6H2O

Most of the water is condensed out, and the gases are further cooled; the nitric oxide that was produced is oxidized to nitrogen dioxide, which is then dimerized into nitrogen tetroxide:

- 2NO + O2 → 2NO2

- 2NO2 ⇌ N2O4

and the remainder of the water is removed as nitric acid. The gas is essentially pure nitrogen dioxide, which is condensed into dinitrogen tetroxide in a brine-cooled liquefier.

Dinitrogen tetroxide is can also be made through the reaction of concentrated nitric acid and metallic copper. This synthesis is more practical in a laboratory setting and is commonly used as a demonstration or experiment in undergraduate chemistry labs. The oxidation of copper by nitric acid is a complex reaction forming various nitrogen oxides of varying stability which depends on the concentration of the nitric acid, presence of oxygen, and other factors. The unstable species further react to form nitrogen dioxide which is then purified and condensed to form dinitrogen tetroxide.

Use as a rocket propellant

Nitrogen tetroxide is used as an oxidizer in one of the more important rocket propellants because it can be stored as a liquid at room temperature. In early 1944 research on the usability of dinitrogen tetroxide as an oxidizing agent for rocket fuel was conducted by German scientists, although the Nazis only used it to a very limited extent as an additive for S-Stoff (fuming nitric acid). It became the storable oxidizer of choice for many rockets in both the United States and USSR by the late 1950s. It is a hypergolic propellant in combination with a hydrazine-based rocket fuel. One of the earliest uses of this combination was on the Titan family of rockets used originally as ICBMs and then as launch vehicles for many spacecraft. Used on the U.S. Gemini and Apollo spacecraft and also on the Space Shuttle, it continues to be used as stationkeeping propellant on most geo-stationary satellites, and many deep-space probes. It now seems likely that NASA will continue to use this oxidizer in the next-generation 'crew-vehicles' which will replace the shuttle. It is also the primary oxidizer for Russia's Proton rocket.

When used as a propellant, dinitrogen tetroxide is usually referred to simply as 'Nitrogen Tetroxide' and the abbreviation 'NTO' is extensively used. Additionally, NTO is often used with the addition of a small percentage of nitric oxide, which inhibits stress-corrosion cracking of titanium alloys, and in this form, propellant-grade NTO is referred to as "Mixed Oxides of Nitrogen" or "MON". Most spacecraft now use MON instead of NTO; for example, the Space Shuttle reaction control system used MON3 (NTO containing 3wt%NO).[6]

The Apollo-Soyuz mishap

On 24 July 1975, NTO poisoning affected the three U.S. astronauts on board the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project during its final descent. This was due to a switch negligently, or accidentally, left in the wrong position, which allowed NTO fumes to vent out of the Apollo spacecraft then back in through the cabin air intake from the outside air after the external vents were opened. One crew member lost consciousness during descent. Upon landing, the crew was hospitalized for 14 days for chemical-induced pneumonia and edema.[7]

Power generation using N2O4

The tendency of N2O4 to reversibly break into NO2 has led to research into its use in advanced power generation systems as a so-called dissociating gas.[8] "Cool" dinitrogen tetroxide is compressed and heated, causing it to dissociate into nitrogen dioxide at half the molecular weight. This hot nitrogen dioxide is expanded through a turbine, cooling it and lowering the pressure, and then cooled further in a heat sink, causing it to recombine into nitrogen tetroxide at the original molecular weight. It is then much easier to compress to start the entire cycle again. Such dissociative gas Brayton cycles have the potential to considerably increase efficiencies of power conversion equipment.[9]

Chemical reactions

Intermediate in the manufacture of nitric acid

Nitric acid is manufactured on a large scale via N2O4. This species reacts with water to give both nitrous acid and nitric acid:

- N2O4 + H2O → HNO2 + HNO3

The coproduct HNO2 upon heating disproportionates to NO and more nitric acid. When exposed to oxygen, NO is converted back into nitrogen dioxide:

- 2 NO + O2 → 2 NO2

The resulting NO2 (and N2O4, obviously) can be returned to the cycle to give the mixture of nitrous and nitric acids again.

Synthesis of metal nitrates

N2O4 behaves as the salt [NO+] [NO3−], the former being a strong oxidant:

- 2 N2O4 + M → 2 NO + M(NO3)2

If metal nitrates are prepared from N2O4 in completely anhydrous conditions, a range of covalent metal nitrates can be formed with many transition metals. This is because there is a thermodynamic preference for the nitrate ion to bond covalently with such metals rather than form an ionic structure. Such compounds must be prepared in anhydrous conditions, since the nitrate ion is a much weaker ligand than water, and if water is present the simple hydrated nitrate will form. The anhydrous nitrates concerned are themselves covalent, and many, e.g. anhydrous copper nitrate, are volatile at room temperature. Anhydrous titanium nitrate sublimes in vacuum at only 40 °C. Many of the anhydrous transition metal nitrates have striking colours. This branch of chemistry was developed by Clifford Addisson and Noramn Logan at Nottingham University in the UK during the 1960s and 1970s when highly efficient desiccants and dry boxes started to become available.

References

- ↑ International Chemical Safety Card

- 1 2 P.W. Atkins and J. de Paula, Physical Chemistry (8th ed., W.H. Freeman, 2006) p.999

- ↑ Henry A. Bent Dimers of Nitrogen Dioxide. II. Structure and Bonding Inorg. Chem., 1963, 2 (4), pp 747–752

- ↑ R.H. Petrucci, W.S. Harwood and F.G. Herring General Chemistry (8th ed., Prentice-Hall 2002), p.420

- ↑ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. "Inorganic Chemistry" Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ↑

- ↑ Sotos, John G., MD. "Astronaut and Cosmonaut Medical Histories", May 12, 2008, accessed April 1, 2011.

- ↑ Stochl, Robert J. (1979). Potential performance improvement by using a reacting gas (nitrogen tetroxide) as the working fluid in a closed Brayton cycle (PDF) (Technical report). NASA. TM-79322.

- ↑ Ragheb, R. "Nuclear Reactors Concepts and Thermodynamic Cycles" (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dinitrogen tetroxide. |

- International Chemical Safety Card 0930

- National Pollutant Inventory – Oxides of nitrogen fact sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards: Nitrogen tetroxide

- Air Liquide Gas Encyclopedia: NO2 / N2O4

- Poliakoff, Martyn (2009). "The Chemistry of Lunar Lift-Off: Our Apollo 11 40th Anniversary Special". The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham.