Nuclear magnetic resonance quantum computer

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) quantum computing is one of the several proposed approaches for constructing a quantum computer, that uses the spin states of molecules as qubits. NMR differs from other implementations of quantum computers in that it uses an ensemble of systems, in this case molecules, rather than a single pure state qubit.

Initially the approach was to use the spin properties of atoms of particular molecules in a liquid sample as qubits - this is known as liquid state NMR (LSNMR). This approach has since been superseded by solid state NMR (SSNMR) as a means of quantum computation.

Overview of Liquid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Quantum Information Processing

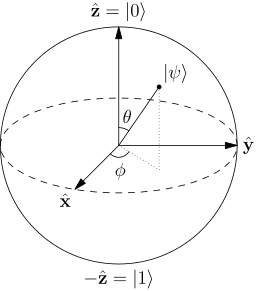

The ideal picture of liquid state NMR (LSNMR) quantum information processing (QIP) is based on a molecule of which some of its atom’s nuclei behave as spin-½ systems. Depending on which nuclei we are considering they will have different energy levels and different interaction with its neighbours and so we can treat them as distinguishable qubits. In this system we tend to consider the inter-atomic bonds as the source of interactions between qubits and exploit these spin-spin interactions to perform 2-qubit gates such as CNOTs that are necessary for universal quantum computation. In addition to the spin-spin interactions native to the molecule an external magnetic field can be applied (in NMR laboratories) and these impose single qubit gates. By exploiting the fact that different spins will experience different local fields we have control over the individual spins.

The picture described above is far from realistic since we are treating a single molecule. NMR is performed on an ensemble of molecules, usually with as many as 10^15 molecules. This introduces complications to the model, one of which is introduction of decoherence. In particular we have the problem of an open quantum system interacting with a macroscopic number of particles near thermal equilibrium (~mK to ~300 K). This has led the development of decoherence suppression techniques that have spread to other disciplines such as trapped ions. The other significant issue with regards to working close to thermal equilibrium is the mixedness of the state. This required the introduction of ensemble quantum processing, whose principal limitation is that as we introduce more logical qubits into our system we require larger samples in order to attain discernable signals during measurement.

Overview of Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Quantum Information Processing

Solid state NMR (SSNMR) differs from LSNMR in that we have a solid state sample, for example a nitrogen vacancy diamond lattice rather than a liquid sample. This has many advantages such as lack of molecular diffusion decoherence, lower temperatures can be achieved to the point of suppressing phonon decoherence and a greater variety of control operations that allow us to overcome one of the major problems of LSNMR that is initialisation. Moreover, as in a crystal structure we can localize precisely the qubits, we can measure each qubit individually, instead of having an ensamble measurement as in LSNMR.

History of NMR Quantum Information Processing

Liquid state NMR Quantum Information Processing was first theoretically introduced independently by Cory, Fahmy and Havel[1] and Gershenfeld and Chuang[2] in 1997. The first experimental demonstration of a liquid NMR quantum computation was reported soon afterwards.

In 1998, Kane proposed the first solid-state based NMR quantum computer, using doped silicon devices in which the nuclear spins of the donor atoms play the role of qubits.

Some early success was obtained in performing quantum algorithms in NMR systems due to the relative maturity of NMR technology. For instance, in 2001 researchers at IBM reported the successful implementation of Shor's algorithm in a 7-qubit NMR quantum computer.[3]

However, even from the early days, it was recognized that NMR quantum computers would never be very useful due to the poor scaling of the signal to noise ratio in such systems.[4] More recent work, particularly by Caves and others, shows that all experiments in liquid state bulk ensemble NMR quantum computing to date do not possess quantum entanglement, thought to be required for quantum computation. Hence NMR quantum computing experiments are likely to have been only classical simulations of a quantum computer.[5]

Details

The ensemble is initialized to be the thermal equilibrium state (see quantum statistical mechanics). In mathematical parlance, this state is given by the density matrix:

where H is the hamiltonian matrix of an individual molecule and

where is the Boltzmann constant and the temperature.

Operations are performed on the ensemble through radio frequency (RF) pulses applied perpendicular to a strong, static magnetic field, created by a very large magnet. See nuclear magnetic resonance.

Consider applying a magnetic field along the z axis, fixing this as the principal quantization axis, on a liquid sample. The Hamiltonian for a single spin would be given by the Zeeman or chemical shift term:

where is the operator for the z component of the nuclear angular momentum, and is the resonance frequency of the spin, which is proportional to the applied magnetic field.

Considering the molecules in the liquid sample to contain two spin ½ nuclei, the system Hamiltonian will have two chemical shift terms and a dipole coupling term:

Control of a spin system can be realized by means of selective RF pulses applied perpendicular to the quantization axis. In the case of a two spin system as described above, we can distinguish two types of pulses: “soft” or spin-selective pulses, whose frequency range encompasses one of the resonant frequencies only, and therefore affects only that spin; and “hard” or nonselective pulses whose frequency range is broad enough to contain both resonant frequencies and therefore these pulses couple to both spins. For detailed examples of the effects of pulses on such a spin system, the reader is referred to Section 2 of work by Cory et al.[6]

References

- ↑ Cory, David G.; Fahmy, Amr F.; Havel, Timothy F. (1997-03-04). "Ensemble quantum computing by NMR spectroscopy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 94 (5): 1634–1639. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.1634C. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1634. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 19968

. PMID 9050830.

. PMID 9050830. - ↑ Gershenfeld, Neil A.; Chuang, Isaac L. (1997-01-17). "Bulk Spin-Resonance Quantum Computation". Science. 275 (5298): 350–356. doi:10.1126/science.275.5298.350. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 8994025.

- ↑ Vandersypen LM, Steffen M, Breyta G, Yannoni CS, Sherwood MH, Chuang IL (2001). "Experimental realization of Shor's quantum factoring algorithm using nuclear magnetic resonance". Nature. 414 (6866): 883–887. arXiv:quant-ph/0112176

. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..883V. doi:10.1038/414883a. PMID 11780055.

. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..883V. doi:10.1038/414883a. PMID 11780055. - ↑ Warren WS (1997). "The usefulness of NMR quantum computing". Science. 277 (5332): 1688–1689. doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1688.

- ↑ Menicucci NC, Caves CM (2002). "Local realistic model for the dynamics of bulk-ensemble NMR information processing". Physical Review Letters. 88 (16). arXiv:quant-ph/0111152

. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88p7901M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.167901.

. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88p7901M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.167901. - ↑ Cory D.; et al. (1998). "Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: An experimentally accessible paradigm for quantum computing". Physica D. 120. arXiv:quant-ph/9709001

. Bibcode:1998PhyD..120...82C. doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(98)00046-3.

. Bibcode:1998PhyD..120...82C. doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(98)00046-3.