Origins of the War of 1812

| Origins of the War of 1812 |

|---|

The War of 1812, a war between the United States and Great Britain, and Britain's Indian allies, lasted from 1812 to 1815. The U.S. declared war and historians have long debated the multiple factors behind that decision.[1]

There were several immediate stated causes for the U.S. declaration of war: First, a series of trade restrictions introduced by Britain to impede American trade with France, a country with which Britain was at war (the U.S. contested these restrictions as illegal under international law);[2] second, the impressment (forced recruitment) of U.S. seamen into the Royal Navy; third, the British military support for American Indians who were offering armed resistance to the expansion of the American frontier to the Northwest; fourth, a possible desire on the part of the United States to annex Canada.[3] An implicit but powerful motivation for the Americans was the desire to uphold national honor in the face of what they considered to be British insults (such as the Chesapeake affair).[4]

American expansion into the Northwest (Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin) was impeded by Indian raids. Some Canadian historians in the early 20th century maintained that Americans had wanted to seize parts of Canada, a view that many Canadians still share, while others argue that inducing the fear of such a seizure had merely been a U.S. tactic designed to obtain a bargaining chip.[5] Some members of the British Parliament at the time[6] and dissident American politicians such as John Randolph of Roanoke[7] claimed that land hunger rather than maritime disputes was the main motivation for the American declaration. However, some historians, both Canadian and American, retain the view that desire to annex all or part of Canada was an American goal.[8] Although the British made some concessions before the war on neutral trade, they insisted on the right to reclaim their deserting sailors. The British also had the long-standing goal of creating a large "neutral" Indian state that would cover much of Ohio, Indiana and Michigan. They made the demand as late as 1814 at the peace conference, but lost battles that would have validated their claims.[9][10]

The war was fought in four theatres: on the oceans, where the warships and privateers of both sides preyed on each other's merchant shipping; along the Atlantic coast of the U.S., which was blockaded with increasing severity by the British, who also mounted large-scale raids in the later stages of the war; on the long frontier, running along the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River, which separated the U.S. from Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec); and finally along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. During the course of the war, both the Americans and British launched invasions of each other's territory, all of which were unsuccessful or gained only temporary success. At the end of the war, the British held parts of Maine and some outposts in the sparsely populated West while the Americans held Canadian territory near Detroit, but these occupied territories were restored at the end of the war.

In the United States, battles such as New Orleans and the earlier successful defence of Baltimore (which inspired the lyrics of the U.S. national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner) produced a sense of euphoria over a "second war of independence" against Britain. It ushered in an "Era of Good Feelings," in which the partisan animosity that had once verged on treason practically vanished. Canada also emerged from the war with a heightened sense of national feeling and solidarity. Britain, which had regarded the war as a sideshow to the Napoleonic Wars raging in Europe, was less affected by the fighting; its government and people subsequently welcomed an era of peaceful relations with the United States.

British goals

The British were engaged in a life-and-death war with Napoleon and could not allow the Americans to help the enemy, regardless of their lawful neutral rights to do so. As Horsman explains, "If possible, England wished to avoid war with America, but not to the extent of allowing her to hinder the British war effort against France. Moreover...a large section of influential British opinion, both in the government and in the country, thought that America presented a threat to British maritime supremacy." [11]

Defeating Napoleon

The British had two goals: All parties were committed to the defeat of France, and this required sailors (hence the need for impressment), and it required all-out commercial war against France (hence the restrictions imposed on American merchant ships). On the question of trade with America the British parties split. As Horsman argues, "Some restrictions on neutral commerce were essential for England in this period. That this restriction took such an extreme form after 1807 stemmed not only from the effort to defeat Napoleon, but also from the undoubted jealousy of America's commercial prosperity that existed in England. America was unfortunate in that for most of the period from 1803 to 1812 political power in England was held by a group that was pledged not only to the defeat of France, but also to a rigid maintenance of Britain's commercial supremacy."[12] That group was weakened by Whigs friendly to the U.S. in mid-1812 and the policies were reversed, but too late for the U.S. had already declared war. By 1815 Britain was no longer controlled by politicians dedicated to commercial supremacy, so that cause had vanished.

The British were hindered by weak diplomats in Washington (such as David Erskine) who misrepresented British policy and by communications that were so slow the Americans did not learn of the reversal of policy until they had declared war.

When Americans proposed a truce based on British ending impressment, Britain refused, because it needed those sailors. Horsman explains, "Impressment, which was the main point of contention between England and America from 1803 to 1807, was made necessary primarily because of England's great shortage of seamen for the war against Napoleon. In a similar manner the restrictions on American commerce imposed by England's Orders in Council, which were the supreme cause of complaint between 1807 and 1812, were one part of a vast commercial struggle being waged between England and France." [12]

Creating an Indian barrier state between U.S. and Canada

The British also had the long-standing goal of creating an Indian barrier state, a large "neutral" Indian state that would cover most of the Old Northwest and be a barrier between the western parts of the United States and Canada. It would be independent of the United States and under the tutelage of the British, who would use it to block American expansion and to build up their control of the fur trade.[13] They made the demand as late as 1814 at the peace conference, but dropped the demand. Their position had been weakened by the collapse of Tecumseh's Confederacy after the Battle of the Thames, but the British also simply no longer considered the goal worth conflict with the United States. Much of the proposed buffer state remained largely under British and Indian control throughout the war.[9][14]

American goals

There were several immediate stated causes for the U.S. declaration of war. First, a series of trade restrictions called the Orders in Council (1807) introduced by Britain to impede American trade with France, a country with which Britain was at war; the U.S. contested these restrictions as illegal under international law.[2] Second, the impressment (forced recruitment) of U.S. citizens into the Royal Navy. Third, the alleged British military support for American Indians who were offering armed resistance to the United States.[3] An unstated but powerful motivation for the Americans was the need to uphold national honor in the face of British insults (such as the Chesapeake affair.)[4] There also may have been an American desire to annex Canada.

British support for Indian raids

Indians based in the Northwest Territory, comprising the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, had organized in opposition to American settlement, and were being supplied with weapons by British traders in Canada. Britain was not trying to provoke a war, and at one point cut its allocations of gunpowder to the tribes, but it was trying to build up its fur trade and friendly relations with potential military allies.[15] Although Britain had ceded the area to the United States in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, it had the long-term goal of creating a "neutral" or buffer Indian state in the area that would block further American growth.[16] The Indian nations generally followed Tenskwatawa (the Shawnee Prophet and the brother of Tecumseh, who since 1805 had preached his vision of purifying his society by expelling the "Children of the Evil Spirit" (the American settlers).[17]

Pratt says:

- "There is ample proof that the British authorities did all in their power to hold or win the allegiance of the Indians of the Northwest with the expectation of using them as allies in the event of war. Indian allegiance could be held only by gifts, and to an Indian no gift was as acceptable as a lethal weapon. Guns and ammunition, tomahawks and scalping knives were dealt out with some liberality by British agents."[18]

Raiding grew more common in 1810 and 1811; Westerners in Congress found the raids intolerable and wanted them permanently ended.[19][20]

American expansionism

Historians have considered the idea that American expansionism was one cause of the war. The American expansion into the Northwest—Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin—was being blocked by Indians and that was a major cause animating the Westerners. American historian Walter Nugent in his history of American expansionism argues that expansion into the Midwest "was not the only American objective, and indeed not the immediate one area but it was an objective."[21]

For many decades the British had planned to set up a new country in the Midwest, controlled by the Indians, who would be in turn strongly supported by the British military. They also wanted to set up a buffer state based in Florida.[22] Britain made the Midwestern buffer state an explicit demand at the peace conference in 1814. Tecumseh, the Indians' main leader, had been killed at the Battle of the Thames, but British and Indian troops continued to hold the proposed buffer state's territory until war's end. Despite this, the British dropped the demand at the peace conference.[23]

Annexation

More controversy is the question whether an American war goal was to permanently acquire Canadian lands (especially western Ontario), or whether it was planned to seize the area temporarily as a bargaining chip. The American desire for Canadian land has been a staple in Canadian public opinion since the 1830s, and was much discussed among historians before 1940, but has become less popular since then. The idea was first developed by Marxist historian Louis Hacker and refined by diplomatic specialist Julius Pratt.[24] In 1925, Pratt argued that Western Americans were incited to war by the prospect of seizing Canada.[25] Pratt's argument supported the belief of many Canadians, especially in Ontario, where fear of American expansionism was a major political element. To this day the notion still survives among Canadians.[26]

In 2010 American historian Alan Taylor examined the political dimension of the annexation issue as Congress debated whether to declare war in 1811-12. The Federalist party was strongly opposed to war and to annexation, as were the northeastern states. The majority in Congress was held by the Jeffersonian Republican party, which split on the issue. One faction wanted to permanently expel Britain and annex Canada. John Randolph of Roanoke, representing Virginia, commented, "Agrarian greed not maritime right urges this war. We have heard but one word - like the whipporwill's one monotonous tone: Canada! Canada! Canada!"[27]The other faction, based in the South, said that acquiring new territory in the north would give the northern states too much power, and opposed the incorporation into Canada of a Catholic population which it viewed as "unfit by faith, language and illiteracy for republican citizenship." The Senate held a series of debates, and twice voted on proposals to explicitly endorse annexation, neither of which passed, although the second one only failed because of a proviso stating that Canada could be returned to British rule after begin annexed. War was declared with no mention of annexation although widespread support existed among the War Hawks for it.

Even James Monroe and Henry Clay, key officials in the government, expected to gain at least Upper Canada from a successful war. Interestingly, American commanders like General William Hull and Alexander Smythe issued proclamations to Canadians and their troops assuring them that annexations would in fact occur during the war. Smythe wrote to his troops that when they entered Canada "You enter a country that is to become on elf the United States. You will arrive among a people who are to become your fellow-citizens." [28]

Seizing Canada as a bargaining chip

Today historians generally agree that an invasion and temporary seizure of Canada was the central American military strategy once the war began. Given British control of the oceans, there was no other way to actively fight against British interests. President Madison Believe that food supplies from Canada were essential to the British overseas empire in the West Indies, and that an American seizure would be an excellent bargaining chip at the peace conference. During the war, some Americans speculated that they might as well keep all of Canada. Thomas Jefferson, for example, although now out of power, argued that expulsion of British interests from nearby Canada would remove a long-term threat to American republicanism. New Zealand historian J.G.A. Stagg argues that Madison and his advisors believed that conquest of Canada would be easy and that economic coercion would force the British to come to terms by cutting off the food supply for their highly valuable West Indies sugar colonies. Furthermore, possession of Canada would be a valuable bargaining chip. Stagg suggests frontiersmen demanded the seizure of Canada not because they wanted the land (they had plenty), but because the British were thought to be arming the Indians and thereby blocking settlement of the west.[29] As Horsman concludes, "The idea of conquering Canada had been present since at least 1807 as a means of forcing England to change her policy at sea. The conquest of Canada was primarily a means of waging war, not a reason for starting it."[30] Hickey flatly states, "The desire to annex Canada did not bring on the war." [31] Brown (1964) concludes, "The purpose of the Canadian expedition was to serve negotiation not to annex Canada."[32] Burt, a Canadian scholar, but also a professor at an American university, agrees completely, noting that Foster, the British minister to Washington, also rejected the argument that annexation of Canada was a war goal.[33] However, Foster also rejected the possibility of a declaration of war, despite having dinner with several of the more prominent War Hawks, so his judgement in these matters can be questioned.

However, historian J. C. A. Stagg states that, "... had the War 1812 been a successful military venture, the Madison administration would have been reluctant to have returned occupied Canadian territory to the enemy."[34] Other authors concur, one stating, "Expansion was not the only American objective, and indeed not the immediate one. But it was an objective",[35] and that "The American yearning to absorb Canada was long-standing...In 1812 it became part of a grand strategy."[36] Another suggests that "Americans harboured 'manifest destiny' ideas of Canadian annexation throughout the nineteenth century."[37] A third states that "[t]he [American] belief that the United States would one day annex Canada had a continuous existence from the early days of the War of Independence to the War of 1812 [and] was a factor of primary importance in bringing on the war."[38] Another says that "acquiring Canada would satisfy America's expansionist desires" .[39] Historian Spencer Tucker tells us that "War Hawks were eager to wage war with the British, not only to end Indian depredations in the Midwest but also to seize Canada and perhaps Spanish Florida."[40]

Inhabitants of Ontario

The majority of the inhabitants of Upper Canada (Ontario) were Americans, some of them exiled (United Empire Loyalists) and most of them recent immigrants. The Loyalists were extremely hostile to union with the U.S., while the other settlers seem to have been uninterested and remained neutral during the war. The Canadian colonies were thinly populated and only lightly defended by the British Army, and some Americans believed that the many in Upper Canada would rise up and greet an American invading army as liberators.[41] The combination implied an easy conquest. Once the war began retired president Thomas Jefferson warned that the British presence posed a grave threat, pointing to "The infamous intrigues of Great Britain to destroy our government....and with the Indians to Tomahawk our women and children, prove that the cession of Canada, their fulcrum for these Machiavellian levers, must be a sine qua non at a treaty of peace. Jefferson predicted in late 1812, "the acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us the experience for the attack on Halifax, the next and final expulsion of England from the American continent."[42]

Maass argued in 2015 that the expansionist theme is a myth that goes against the "relative consensus among experts that the primary U.S. objective was the repeal of British maritime restrictions. He argues that consensus among scholars is that The United States went to war "because six years of economic sanctions had failed to bring Britain to the negotiating table, and threatening the Royal Navy’s Canadian supply base was their last hope." Maass agrees that theoretically expansionism might have tempted Americans, but finds that "leaders feared the domestic political consequences of doing so. Notably, what limited expansionism there was focused on sparsely populated western lands rather than the more populous eastern settlements [of Canada]."[43]

Violations of American rights

The long wars between Britain and France (1793–1815) led to repeated complaints by the U.S. that both powers violated America's right as a neutral to trade with both sides. Furthermore, Americans complained loudly that British agents in Canada were supplying munitions to hostile Native American tribes living in United States territory.

Starting in the mid-1790s the Royal Navy, short of manpower, began boarding American merchant ships in order to seize American and British sailors from American vessels. Although this policy of impressment was supposed to reclaim only British subjects, the law of Britain and most countries defined nationality by birth whereas the United States allowed individuals who had been resident in America for some time to adopt American citizenship. There were, therefore, large numbers of individuals who were British by British law but American by American law. The confusion was compounded by the refusal of Jefferson and Madison to issue any official citizenship documents: their position was that all persons serving on American ships were to be regarded as US citizens and that no further evidence was required. This stance was motivated by the advice of Albert Gallatin, who had calculated that half of American deep-sea merchant seamen - 9,000 men - were British subjects. Allowing the Royal Navy to reclaim these men would destroy both the US economy and the vital customs revenue of the government.[44] Any sort of accommodation would jeopardize these men, and so concords such as the proposed Monroe-Pinkney Treaty (1806) between the U.S. and Britain were rejected by Jefferson.

To fill the need for some sort of identification, US consuls provided unofficial papers. However, these relied on unverifiable declarations by the individual concerned for evidence of citizenship, and the large fees paid for the documents made them a lucrative sideline. In turn, British officers- short of personnel and convinced, not entirely unreasonably, that the US flag covered a large number of British deserters- tended to treat such papers with scorn. Between 1806 and 1812 about 6,000 seamen were impressed and taken against their will into the Royal Navy[45] of which 3,800 were subsequently released.[46]

Honour

Historian Norman Risjord has emphasized the central importance of honour as a cause the war.[47] Americans of every political stripe saw the need to uphold national honor, and to reject the treatment of the United States by Britain as a third class nonentity. Americans talked incessantly about the need for force in response.[48] This quest for honour was a major cause of the war in the sense that most Americans who were not involved in mercantile interests or threatened by Indian attack strongly endorsed the preservation of national honour.[49] The humiliating attack by the HMS Leopard against the USS Chesapeake in June 1807 was a decisive event.[50] Many Americans called for war, but Jefferson held back, insisting that economic warfare would prove more successful. Jefferson initiated economic warfare, especially in the form of embargoing or refusing to sell products to Britain. It proved a failure, that did not deter the British but it seriously damaged American industry had alienated the mercantile cities of the Northeast that were so seriously hurt. Historians have demonstrated the motive power of honor in shaping public opinion in a number of states, including Massachusetts,[51] Ohio,[52] Pennsylvania,[53][54] Tennessee,[55] and Virginia,[56] as well as the territory of Michigan.[57] On June 3, 1812, the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, chaired by fire-eater John C. Calhoun called for a declaration of war in ringing phrases, denouncing Britain's "lust for power," "unbounded tyranny," and "mad ambition." James Roark says, "These were fighting words in a war that was in large measure about insult and honour."[58] Calhoun reaped much of the credit.[59]

In terms of honour, the conclusion of the war, especially the spectacular defeat of the main British invasion army at New Orleans, did restore the American sense of honor. Historian Lance Banning says:

- National honour, the reputation of republican government, and the continuing supremacy of the Republican party had seemed to be at stake.... National honour had [now] been satisfied....Americans celebrated the end of the struggle with a brilliant burst of national pride. They felt that they had fought a second war for independence, and had won. If little had been gained, nothing had been lost in a contest the greatest imperial power on the earth.[60]

The British respected American honor as well, and never again engage in this sort of bullying and harassment of American maritime interests as an era of peaceful relations

American economic motivations

The failure of Jefferson's embargo and Madison's economic coercion, according to Horsman, "made war or absolute submission to England the only alternatives, and the latter presented more terrors to the recent colonists. The war hawks came from the West and the South, regions that had supported economic warfare and were suffering the most from British restrictions at sea. The merchants of New England earned large profits from the wartime carrying trade, in spite of the numerous captures by both France and England, but the western and southern farmers, who looked longingly at the export market, were suffering a depression that made them demand war".[61]

Incidents leading up to the war

This dispute came to the forefront with the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807, when the British warship HMS Leopard fired on and boarded the American warship USS Chesapeake, killing three and carrying off four deserters from the Royal Navy. (Only one was a British citizen and he was subsequently hanged; the other three were American citizens and were later returned, though the last two not until 1812.) The American public was outraged by the incident, and many called for war in order to assert American sovereignty and national honor.

The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair followed closely on the similar Leander Affair, which had resulted in President Jefferson banning certain British warships and their captains from American ports and waters. Whether in response to this incident or the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, President Jefferson banned all foreign armed vessels from American waters, except those bearing dispatches. In December 1808, an American officer expelled the schooner HMS Sandwich from Savannah, Georgia, after she had entered with dispatches for the British Consul there.

Meanwhile, Napoleon's Continental System (beginning 1806) and the British Orders in Council (1807) established embargoes that made international trade precarious. From 1807 to 1812, about 900 American ships were seized as a result.[62] The U.S. responded with the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited American ships from sailing to any foreign ports and closed American ports to British ships. Jefferson's embargo was especially unpopular in New England, where merchants preferred the indignities of impressment to the halting of overseas commerce. This discontent contributed to the calling of the Hartford Convention in 1814.

The Embargo Act had no effect on Great Britain and France and was replaced by the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which lifted all embargoes on American shipping except for those bound for British or French ports. As this proved to be unenforceable, the Non-Intercourse Act was replaced in 1810 by Macon's Bill Number 2. This lifted all embargoes but offered that if either France or Great Britain were to cease their interference with American shipping, the United States would reinstate an embargo on the other nation. Napoleon, seeing an opportunity to make trouble for Great Britain, promised to leave American ships alone, and the United States reinstated the embargo with Great Britain and moved closer to declaring war.[63]

Exacerbating the situation, Sauk Indians who controlled trade on the Upper Mississippi were displeased with the U.S. Government after the 1804 treaty between Quashquame and William Henry Harrison. This treaty ceded Sauk territory in Illinois and Missouri to the U.S.; the Sauk felt this treaty was unjust, that Quashquame was unauthorized to sign away land, and that he was unaware of what he was signing. The establishment of Fort Madison in 1808 on the Mississippi further aggravated the Sauk, and led many, including Black Hawk, to side with the British before the war broke out. Sauk and allied Indians, including the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), were very effective fighters for the British on the Mississippi, helping to defeat Fort Madison and Fort McKay in Prairie du Chien.

Oxford historian Paul Langford looks at the decisions by the British government in 1812:

- The British ambassador in Washington [Erskine] brought affairs almost to an accommodation, and was ultimately disappointed not by American intransigence but by one of the outstanding diplomatic blunders made by a Foreign Secretary. It was Canning who, in his most irresponsible manner and apparently out of sheer dislike of everything American, recalled the ambassador Erskine and wrecked the negotiations, a piece of most gratuitous folly. As a result, the possibility of a new embarrassment for Napoleon turned into the certainty of a much more serious one for his enemy. Though the British cabinet eventually made the necessary concessions on the score of the Orders-in-Council, in response to the pressures of industrial lobbying at home, its action came too late…. The loss of the North American markets could have been a decisive blow. As it was by the time the United States declared war, the Continental System [of Napoleon] was beginning to crack, and the danger correspondingly diminishing. Even so, the war, inconclusive though it proved in a military sense, was an irksome and expensive embarrassment which British statesman could have done much more to avert.[64]

Declaration of war

In the United States House of Representatives, a group of young Democratic-Republicans known as the "War Hawks" came to the forefront in 1811, led by Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. The War Hawks advocated going to war against Great Britain for all of the reasons listed above, though concentrating on the grievances more than the territorial expansion.

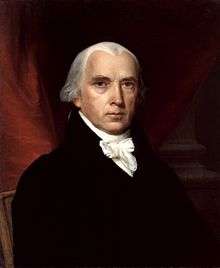

On the first of June 1812, President James Madison gave a speech to the U.S. Congress, recounting American grievances against Great Britain, though not specifically calling for a declaration of war. After Madison's speech, the House of Representatives quickly voted (79 to 49) to declare war, and the Senate by 19 to 13. The conflict formally began on 18 June 1812 when Madison signed the measure into law. This was the first time that the United States had declared war on another nation, and the Congressional vote would prove to be the closest vote to declare war in American history. None of the 39 Federalists in Congress voted in favor of the war; critics of war subsequently referred to it as "Mr. Madison's War." [65]

See also

- Chronology of the War of 1812

- Opposition to the War of 1812

- Results of the War of 1812

- War of 1812

- War of 1812 bibliography

Notes

- ↑ Jasper M. Trautsch, "The Causes of the War of 1812: 200 Years of Debate," Journal of Military History (Jan 2013) 77#1 pp 273-293.

- 1 2 Caffery, pp.56–58

- 1 2 Caffery, pp.101–104

- 1 2 Norman K. Risjord, "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks, and the Nation's Honor." William And Mary Quarterly 1961 18(2): 196–210. in JSTOR

- ↑ Bowler, pp. 11–32

- ↑ George Canning, Address respecting the war with America, Hansard (House of Commons), 18 February 1813

- ↑ Fregosi, Paul (1989). Dreams of Empire. Hutchinson. p. 328. ISBN 0-09-173926-8.

- ↑ J.C.A Stagg (1983), Mr Madison's War, pg. 4

- 1 2 Dwight L. Smith, "A North American Neutral Indian Zone: Persistence of a British Idea" Northwest Ohio Quarterly 1989 61(2–4): 46–63

- ↑ Francis M. Carroll, A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian-American Boundary, 1783–1842, 2001, page 23

- ↑ Horsman (1962) p. 264

- 1 2 Horsman (1962) p. 265

- ↑ Dwight L. Smith"A North American Neutral Indian Zone: Persistence of a British Idea." Northwest Ohio Quarterly 61#2-4 (1989): 46-63.

- ↑ Francis M. Carroll (2001). A Good and Wise Measure: The Search for the Canadian-American Boundary, 1783-1842. U. of Toronto Press. p. 24.

- ↑ Mark Zuehlke, For Honour's Sake: The War of 1812 and the Brokering of an Uneasy Peace (2006) pp 62–62

- ↑ Dwight L. Smith, "A North American Neutral Indian Zone: Persistence of a British Idea", Northwest Ohio Quarterly (1989) 61 (2–4): 46–63.

- ↑ Timothy D. Willig. Restoring the Chain of Friendship: British Policy and the Indians of the Great Lakes, 1783–1815 (2008) p. 207.

- ↑ Julius W. Pratt, A history of United States foreign-policy (1955) p 126

- ↑ David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. Encyclopedia of the War of 1812 (1997) pp. 253, 504

- ↑ Zuehlke, For Honour's Sake, p 62

- ↑ Walter Nugent, Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansionism (2009) ch 3, quoted on page 73.

- ↑ John K. Mahon, "British Strategy and Southern Indians: War of 1812." Florida Historical Quarterly (1966): 285-302. in JSTOR

- ↑ Rodney P Carlisle,J. Geoffrey Golson. Manifest Destiny and the Expansion of America. ABC-CLIO. p. 44.

- ↑ Hacker (1924); Pratt (1925). Goodman (1941) refuted the idea and even Pratt gave it up. Pratt (1955)

- ↑ Julius W. Pratt, "Western Aims in the War of 1812." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1925): 36-50. in JSTOR

- ↑ W. Arthur Bowler, "Propaganda in Upper Canada in the War of 1812," American Review of Canadian Studies (1988) 28:11–32; C.P. Stacey, "The War of 1812 in Canadian History" in Morris Zaslow and Wesley B. Turner, eds. The Defended Border: Upper Canada and the War of 1812 (Toronto, 1964)

- ↑ Fregosi 1989, p. 328.

- ↑ Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies (2010) pp 137-40.

- ↑ Stagg (1983)

- ↑ Horsman (1962) p. 267

- ↑ Hickey (1990) p. 72.

- ↑ Brown p. 128.

- ↑ Burt (1940) pp 305–10.

- ↑ Stagg 1983, p. 4.

- ↑ Nugent, p. 73.

- ↑ Nugent, p. 75.

- ↑ Carlisle & Golson 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Pratt 1925, p. .

- ↑ David Heidler,Jeanne T. Heidler, The War of 1812, pg4

- ↑ Tucker 2011, p. 236.

- ↑ Fred Landon, Western Ontario and the American Frontier (1941) pp 12–22

- ↑ James Laxer (2012). Tecumseh and Brock: The War of 1812. p. 129.

- ↑ Richard W. Maass, “Difficult to Relinquish Territory Which Had Been Conquered”: Expansionism and the War of 1812," Diplomatic History (Jan 2015) 39#1 pp 70-97 doi: 10.1093/dh/dht132 Abstract Online

- ↑ Rodger, Command of the Ocean, p565

- ↑ Hickey (1989) p. 11

- ↑ Rodger, Command of the Ocean, p566

- ↑ Norman K. Risjord, "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks and the Nation's Honor." William and Mary Quarterly: A Magazine of Early American History (1961): 196-210. in JSTOR

- ↑ Robert L. Ivie, "The metaphor of force in prowar discourse: The case of 1812." Quarterly Journal of Speech 68#3 (1982) pp: 240-253.

- ↑ Bradford Perkins, The causes of the War of 1812: National honour or national interest? (1962).

- ↑ Spencer Tucker and Frank T. Reuter, Injured Honor: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, June 22, 1807 (Naval Institute Press, 1996)

- ↑ William Barlow and David O. Powell. "Congressman Ezekiel Bacon of Massachusetts and the Coming of the War of 1812." Historical Journal of Massachusetts 6#2 (1978): 28.

- ↑ William R. Barlow, "Ohio’s Congressmen and the War of 1812." Ohio History 72 (1963): 175-94.

- ↑ Victor Sapio, Pennsylvania and the War of 1812 (University Press of Kentucky, 2015)

- ↑ Martin Kaufman, "War Sentiment in Western Pennsylvania: 1812." Pennsylvania History (1964): 436-448.

- ↑ William A. Walker, "Martial Sons: Tennessee Enthusiasm for the War of 1812." Tennessee Historical Quarterly 20.1 (1961): 20+

- ↑ Edwin M. Gaines, "The Chesapeake Affair: Virginians Mobilize to Defend National Honour." The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (1956): 131-142.

- ↑ William Barlow, "The Coming of the War of 1812 in Michigan Territory." Michigan History 53 (1969): 91-107.

- ↑ James L. Roark; Patricia Cline Cohen; et al. (2011). Understanding the American Promise. p. 259.

- ↑ James H. Ellis (2009). A Ruinous and Unhappy War: New England and the War of 1812. Algora Publishing. pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Lance Banning (1980). The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology. Cornell UP. p. 295.

- ↑ Horsman (1962) p. 266

- ↑ Hickey (1989) p. 19

- ↑ Napoleon had no intention of honoring promise: Hickey, p. 22; Horsman, p. 188.

- ↑ Paul Langford, Modern British Foreign Policy: The Eighteenth Century: 1688-1815 (1976) p 228

- ↑ Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, 1789–1873

References

- Adams, Henry. History of the United States during the Administrations of James Madison (5 vol 1890–91; 2 vol Library of America, 1986). ISBN 0-940450-35-6 Table of contents, the classic political-diplomatic history

- Benn, Carl. The War of 1812 (2003).

- Brown, Roger H. The Republic in Peril: 1812 (1964). on American politics

- Burt, Alfred L. The United States, Great Britain, and British North America from the Revolution to the Establishment of Peace after the War of 1812. (1940)

- Goodman, Warren H. "The Origins of the War of 1812: A Survey of Changing Interpretations," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1941)28#1 pp 171–86. in JSTOR

- Hacker, Louis M. "Western Land Hunger and the War of 1812," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1924), 10#3 pp 365–95. in JSTOR

- Heidler, Donald & J, (eds) Encyclopedia of the War of 1812 (2004) articles by 70 scholars from several countries

- Hickey, Donald. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. University of Illinois Press, 1989. ISBN 0-252-06059-8, by leading American scholar

- Hickey, Donald R. Don't Give Up the Ship! Myths of the War of 1812. (2006) ISBN 0-252-03179-2

- Horsman, Reginald. The Causes of the War of 1812 (1962).

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. "France and Madison's Decision for War 1812," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 50, No. 4. (Mar., 1964), pp. 652–671. in JSTOR

- Maass, Richard W. "'Difficult to Relinquish Territory Which Had Been Conquered': Expansionism and the War of 1812," Diplomatic History (Jan 2015) 39#1 pp 70–97 doi: 10.1093/dh/dht132

- Perkins, Bradford. Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812 (1961) full text online, detailed diplomatic history by American scholar

- Perkins, Bradford. (1962). The Causes of the War of 1812. Krieger

- Pratt, Julius W. A History of United States Foreign Policy (1955)

- Pratt, Julius W. (1925b.) Expansionists of 1812

- Pratt, Julius W. "Western War Aims in the War of 1812," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 12 (June, 1925), 36–50. in JSTOR

- Risjord, Norman K. "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks, and the Nation's Honor," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., XVIII ( April, 1961), 196–210. in JSTOR

- Smelser, Marshall. The Democratic Republic 1801–1815 (1968) general survey of American politics & diplomacy

- Stagg, John C. A. Mr. Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American republic, 1783–1830. (1983), major overview (by New Zealand scholar)

- Stagg, John C. A. "James Madison and the 'Malcontents': The Political Origins of the War of 1812," William and Mary Quarterly (Oct., 1976) in JSTOR

- Stagg, John C. A. "James Madison and the Coercion of Great Britain: Canada, the West Indies, and the War of 1812," in The William and Mary Quarterly (Jan., 1981) in JSTOR

- Taylor, Alan. The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies (2010)

- Taylor, George Rogers, ed. The War of 1812: Past Justifications and Present Interpretations (1963)

- Trautsch, Jasper M. "The Causes of the War of 1812: 200 Years of Debate," Journal of Military History (Jan 2013) 77#1 pp 273–293

External links

- Reading list on the Causes of the War of 1812 compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

-2.png)