Iran–Pakistan relations

|

|

Iran |

Pakistan |

|---|---|

After the independence of Pakistan in August 1947, Iran had the unique distinction of being the first country to internationally recognise the sovereign status of Pakistan.[1] Currently, both countries are economic partners. This cooperation lasted throughout the Cold War, with Iran supporting Pakistan in its conflicts with arch-rival, India.[2] In return, Pakistan supported Iran militarily during the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s. Since 2000, relations between the two states have been relatively normalised, and economical and military collaboration has strengthened the relationship. Both countries are founding members of the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO).

Nevertheless, economic and trade relations continued to expand in both absolute and relative terms, leading to the signing of a Free Trade Agreement between the two countries in 1999.[3] At present, both countries are cooperating and forming alliances in a number of areas of mutual interest, such as fighting the drug trade along their common border and combating the Balochistan insurgency along their border. Iran has expressed an interest joining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.[4][5][6]

Iran has been a respected, popular, and favoured nation among Pakistanis, with 76% of Pakistanis viewing their western neighbour positively, making Pakistan the most pro-Iran nation in the world.[7]

Relations between political executives

The executive governments of Iran and Pakistan are structured differently, with different institutions. In Iran, the President is head of government, while the Supreme Leader is the head of state, with executive authority over the Iranian President.

In Pakistan, the Prime Minister is the head of government only, and his or her "government" or "ministry" directs the executive branch of the government, while the President has no authority over the government, and is constitutionally designated a ceremonial figurehead.

Relations during the Cold War

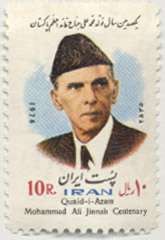

In his book The Frontiers of Pakistan, Iranian scholar Dr. Mujtaba Razvi noted that, "almost without exception, Pakistan has enjoyed very cordial relations with Iran since its inception on 14 August 1947.[1] Iran was the first country to recognise Pakistan as an independent state, and Shah of Iran was the first Head of State to come on a state visit to Pakistan in March 1950".[1] Since 1947, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the Founder of Pakistan, had advocated a pro-Iranian policy, and was the main architect of the policy that Pakistan was to pursue with regard to Iran. At cabinet meetings, Jinnah argued at length for fostering cordial relations with Iran in particular and the Muslim world in general.[1] On several occasion, Jinnah pointed out with great vision that Pakistan could look forward to a genuine and lasting relationship with Iran. He named Raja Ghazanfar Ali Khan as Pakistan's first ambassador to Iran, with a directive to forge fraternal ties based on genuine respect for each other.[1] In May 1949, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan paid his first state visit to Iran. Despite Shia-Sunni divisions, Islamic identity became an important factor in shaping Iranian–Pakistani relations, especially after the Islamic Revolution in Iran. In May 1950, a treaty of friendship was signed by Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan and the Shah of Iran.

Some of the clauses of the treaty of friendship had wider geopolitical significance.[8] Pakistan found a natural partner in Iran after the Indian government chose to support Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who was seeking to export a pan-Arab ideology that threatened many of the more traditional Arab monarchies, a number of which were allied with the Shah.[8] Harsh V. Pant, a foreign policy writer, noted that Iran was a natural ally and model for Pakistan for other reasons as well. Both countries granted each other MFN status for trade purposes; the shah offered Iranian oil and gas to Pakistan on generous terms, and the Iranian and Pakistani armies cooperated to suppress the rebel movement in Baluchistan.[8] During the Shah's era, Iran moved closer to Pakistan in many fields.[1] Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey joined the United States-sponsored Central Treaty Organisation, which extended a defensive alliance along the Soviet Union's southern perimeter.[1] Iran played an important role in the Indo-Pakistani war of 1965, providing Pakistan with nurses, medical supplies, and a gift of 5,000 tons of petroleum. Iran also indicated that it was considering an embargo on oil supplies to India for the duration of the fighting.[1] The Indian government believed that Iran had blatantly favored Pakistan.[1] After the suspension of United States military aid to Pakistan, Iran was reported to have purchased ninety Sabre jet fighter planes from West Germany, and to have sent them on to Pakistan.[1]

Although Pakistan's decision to join the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) in 1955 was largely motivated by its security imperatives regarding India, Pakistan did not sign on until Iran was satisfied that the British Government was not going to obstruct the nationalization of British oil companies in Iran.[1] According to Dr. Mujtaba Razvi, Pakistan likely would not have joined CENTO had Iran not decided to do so.[1]

Iran again played a vital role in Pakistan's 1971 conflict with India, this time supplying military equipment as well as diplomatic support against India. The Shah described the Indian attack as aggression and interference in Pakistan's domestic affairs;[2] in an interview with a Parisian newspaper he openly acknowledged that "We are one hundred percent behind Pakistan".[2] Iranian Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveida followed suit, saying that "Pakistan has been subjected to violence and force."[2] The Iranian leadership repeatedly expressed its opposition to the dismemberment of Pakistan, fearing it would adversely affect the domestic stability and security of Iran[2] by encouraging Kurdish separatists to rise up against the Iranian government.[2] In the same vein, Iran attempted to justify its supplying arms to Pakistan on the grounds that, in its desperation, Pakistan might fall into the Chinese lap.[2] On the other hand, Iran changed its foreign priorities after making a move to maintain good relations with India.

The breakup of Pakistan in December 1971 convinced Iran that extraordinary effort was needed to protect the stability and territorial integrity of its eastern flank. With the emergence of Bangladesh as a separate State, the "Two-nations theory" received a severe blow and questions arose in the Iranian establishment as to whether the residual western part of Pakistan could hold together and remain a single country.[9] Events of this period caused significant perceptional changes in Tehran regarding Pakistan.

When widespread armed insurgency broke out in Pakistan's Balochistan Province in 1973, Iran, fearing the insurgency might spill over into its own Balochistan Province, offered large-scale support.[10] The Iranians provided Pakistan with military hardware (including thirty Huey cobra attack helicopters), intelligence sharing, and $200 million in aid.[11] The government of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto declared its belief that, as in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, India was behind the unrest. However, the Indian government denied any involvement, and claimed that it was fearful of further balkanisation of the subcontinent.[11] After three years of fighting the uprising was suppressed.[11]

In addition to military aid, the Shah of Iran offered considerable developmental aid to Pakistan, including oil and gas on preferential terms.[9] Pakistan was a developing country and small power, while Iran, in the 1960-70s, had the world's fifth largest military and a strong industrial base, and was the clear, undisputed regional superpower.[2][12] However, Iran's total dependence on the United States at that time for its economic development and military build-up had won it the hostility of Arab world.[2] Tensions arose in 1974, when Mohammad Reza Pahlavi refused to attend the Islamic Conference in Lahore because Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi had been invited to it, despite the known hostility between the two.[2] In 1976, Iran again played a vital and influential role by facilitating a rapprochement between Pakistan and Afghanistan.[1]

Iran's reaction to India's 1974 surprise nuclear test detonation (codenamed Smiling Buddha) was muted.[9] During a state visit to Iran in 1977, Bhutto tried to persuade Pahlavi to support Pakistan's own clandestine atomic bomb project.[9] Although the Shah's response is not known, there are indications that he refused to oblige Bhutto.[2]

In July 1977, following political agitation by an opposition alliance, Bhutto was forced out of office in a military coup d'état.[1] The new military government, under General Zia-ul-Haq, was ideologically ultraconservative and Islamically oriented in its nature and approach.[1]

Iranian revolution

Bhutto's ouster was followed a half year later by the Iranian Revolution and overthrow of the Shah of Iran. Iran's new Supreme Leader, the Ayatollah Khomeini, withdrew the country from CENTO and ended its association with the United States.[1] The religiously influenced military government of Zia-ul-Haq and the Islamic Revolution in Iran suited one another well, and as such there was no diplomatic and political cleavage between them.[1] In 1979, Pakistan was one of the first countries in the world to recognize the revolutionary regime in Iran. Responding swiftly to this revolutionary change, Foreign Minister of Pakistan Agha Shahi immediately undertook a state visit to Tehran, meeting with his Iranian counterpart Karim Sanjabi on 10 March 1979.[1] Both expressed confidence that Iran and Pakistan were going to march together to a brighter future.[1] The next day, Agha Shahi held talks with the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, in which developments in the region were discussed.[1] On 11 April 1979, Zia famously declared that "Khomeini is a symbol of Islamic insurgence".[1] Reciprocating President Zia's sentiments, Imam Khomeini, in his letter, called for Muslim unity.[1] He declared: "Ties with Pakistan are based on Islam."[1] By 1981, however, Pakistan, under Zia-ul-Haq, had once again formed close ties with the United States, a position it has remained in since.[1]

Pakistani support for Iran during the Iran–Iraq war

The 1980–88 Iran–Iraq War was a polarizing issue in Pakistan. Despite their long friendship, the militancy of Shia inspired by revolutionary Iran left many Pakistani Sunni feeling deeply threatened.[13] President Zia had to manage his country's security carefully, knowing that Pakistan risked being dragged into a war with its closest neighbor because of its alliance with the United States.[13] In support of the Gulf Cooperation Council, formed in 1981, around 40,000 personnel of the Pakistan Armed Forces were stationed in Saudi Arabia to reinforce the internal and external security of the region.[13] Although high-ranking members of Pakistan Armed Forces strongly objected to the killing of Shia pilgrims in the 1987 Mecca incident in Saudi Arabia, Zia did not issue any orders to Pakistan Armed Forces-Arab Contingent Forces to engage any country militarily.[13]

Despite its stated neutrality, ties to the U.S., and fears of Shia militancy, Pakistan came to be seen as generally pro-Iranian in sentiment.[13] Many Stinger missiles shipped to Pakistan for use by Afghan mujahideen were instead sold to Iran, which proved to be a defining factor for Iran in the Tanker war.[13]

Soviet integration and Afghan civil war

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded fragile Communist Afghanistan to protect its interests in Central Asia and as response to American dominance in the Middle East, in notably Israel, Iran, and many Arab states. In 1980, the Iraqi attack on Iran, and subsequent Soviet support for Iraq, improved Iranian ties with Pakistan.[8] Pakistan focused its covert support on the sectarian Pashtun groups while Iran largely supported the Tajik groups, though they all fought as Afghan mujahideen.[8]

After 1989, both state's policies in Afghanistan became even more divergent as Pakistan, under Benazir Bhutto, explicitly supported Taliban forces in Afghanistan.[14] This resulted in a major breach, with Iran becoming closer to India.[14] As noted by a Pakistani foreign service officer, it was difficult to maintain good relations with Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Iran at the same time, given Iran's long history of rivalry with these states.[14] In 1995 Bhutto paid a lengthy state visit to Iran, which greatly relaxed relations. At a public meeting she spoke highly of Iran and Iranian society.[15] However, increasing activity by Shia militants in Pakistan strained relations further.[8] This was followed by the Taliban's capture of the city of Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, in which thousands of Shias were massacred, according to Amnesty International.[8] The most serious breach in relations came in 1998, after Iran accused Taliban Afghanistan of taking 11 Iranian diplomats, 35 Iranian truck drivers and an Iranian journalist hostage, and later killing them all.[8] Iran massed over 300,000 troops on the Afghan border and threatened to attack the Taliban government, which it had never recognized.[8] This strained relations with Pakistan, as the Taliban were seen as Pakistan's key allies.[8] In May 1998, Iran criticised Pakistan for its nuclear testing in the Chagai region, and held Pakistan accountable for global "atomic proliferation".[16] New Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif acknowledged his country's nuclear capability on 7 September 1997.[17] Before making the announcement, Sharif directed a secret courier to Israel via Pakistan Ambassador to United Nations Inam-ul-Haq and Pakistan Ambassador to the United States Dr. Maliha Lodhi, in which Pakistan gave utmost assurance to Israel that Pakistan would not transfer any aspects of its nuclear technology or materials to Iran.

Bilateral and Multilateral visits in the late 1990s

In 1995, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto paid a state visit to Iran to lay the groundwork for a memorandum on energy, and begin work on an Energy security agreement between the two countries. This was followed by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's visit to Tehran for the 8th OIC Summit Conference on 9–11 December 1997. While there Sharif held talks with President Khatami, with a view to improving bilateral relations, as well as finding a solution to the Afghan crisis.[18]

Chief Executive General Pervez Musharraf paid a two-day visit to Tehran on 8–9 December 1999. This was his first visit to Iran (and third international trip) since his military coup d'état of 12 October 1999 and subsequent seizure of power in Pakistan. In Iran, Musharraf held talks with Iranian President Mohammad Khatami[19] and with the Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.[20] This visit was arranged[21] to allow Musharraf to explain the reasons for his takeover in Pakistan.[22]

The meetings included discussions on the situation in Afghanistan, which were intended to lead both countries to "coordinate the policies of our two countries for encouraging the peace process through reconciliation and dialogue among the Afghan parties".[23][24]

Relations since 2000

Since 2000, relations between Iran and Pakistan have begun to normalize, and economic cooperation has strengthened. The 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States changed the foreign policy priorities of both Iran and Pakistan.[8] The George W. Bush administration's tough stance forced President Pervez Musharraf to support Washington's War on Terror, which ended Taliban rule in Kabul. Though Iranian officials welcomed the move, they soon found themselves encircled by U.S. forces in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and the Persian Gulf.[8]

President Bush's inclusion of the Islamic Republic as part of an "Axis of Evil" also led some Iranian officials to presume that Tehran might be next in line for regime change, ending whatever détente had occurred in Iran–U.S. ties under Khatami.[8] Bush's emphasis on transformative diplomacy and democratization worried Iranian leaders further.[8]

More recently, Iran and Pakistan have joined forces and engaged in co-operation to contain insurgency in Balochistan which has included the severe use of force and been a cause of human rights concern.[25]

Bilateral visits after 2000

In April 2001, the Secretary of Supreme National Security Council Hassan Rowhani (who is President of Iran since August 2013) paid a state visit to Pakistan and met with Pervez Musharraf and his cabinet.[3] During this visit, Iran and Pakistan agreed to put their differences aside and agree on a broad-based government for Afghanistan.[3][26]

Iranian Foreign Minister Kamal Kharazi paid a two-day visit to Islamabad from 29–30 November 2001.[27] Kharazi met with Foreign Minister Abdul Sattar[28] and President Musharraf.[29] Iran and Pakistan vowed to improve their relations, and agreed to help establish a broad-based, multi-ethnic government under U.N. auspices.[30]

The President of Iran, Mohammad Khatami, paid a three-day state visit to Pakistan from 23–25 December 2002, the first visit by an Iranian head of government since 1992.[31] It was a high-level delegation, consisting of the Iranian cabinet, members of the Iranian parliament, Iranian Vice-President and President Khatami.[31] This visit was meant to provide a new beginning to Iran–Pakistan relations.[32][33][34] It would also allow for high-level discussions on the future of the Iran–Pakistan–India pipeline (IPI) project.[35] Khatami met, and had detailed discussions, with both President Musharraf[36][37] and the new Prime Minister Zafarullah Khan Jamali.[38][39] Several accords were signed between Iran and Pakistan in this visit.[40] Khatami also delivered a talk on "Dialogue Among Civilizations," at The Institute of Strategic Studies.[41] The presidential delegation initially visited Islamabad, and then followed that up with a visit to Lahore,[42] where Khatami also paid his respects at the tomb of Allama Sir Muhammad Iqbal.[43] A Joint communique was issued by Iran and Pakistan on the conclusion of Khatami's visit.[44] On his return to Tehran, Khatami evaluated the trip as "positive and fruitful".[45]

As in return, Jamali paid a state visit in 2003 where he held talks with economic cooperation, security of the region, and better bilateral ties between Pakistan and Iran.[46] During this visit, Jamali gave valuable advises to Iranian leadership on their nuclear programme "against the backdrop of the country's" negotiations with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and measures to strengthen economic relations between the two countries.[47]

Military and security

Iranian support for Pakistan dates back to the 1960s when Iran supplied Pakistan with American military weaponry and spare parts after America cut off their military aid to Pakistan.[48] After 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, new Prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto immediately withdrew Pakistan from CENTO and SEATO after Bhutto thought that the military alliances failed to protect or appropriately assist Pakistan and instead alienated the Soviet Union. A serious military cooperation between took place during the Balochistan insurgency phases against the armed separatist movement in 1974–77.[49] Around ~100,000 Pakistan and Iranian troops were involved in quelling the separatist organisations in Balochistan and successfully put the resistance down in 1978–80.[49] In May 2014, the two countries agreed to joint operations against terrorists and drug traffickers in the border regions.[50]

Iran's view on Kashmir issue

On 19 November 2010 Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei appealed to Muslims worldwide to back the freedom struggle in Jammu and Kashmir, equating the dispute with the ongoing conflicts of the Greater Middle East region.

"Today the major duty of the elite of the Islamic Ummah is to provide help to the Palestinian nation and the besieged people of Gaza, to sympathize and provide assistance to the nations of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Occupied Kashmir, to engage in struggle and resistance against the aggressions of the United States, the Zionist Regime..."[51][52] He further said that Muslims should be united and "spread awakening and a sense of responsibility and commitment among Muslim youth throughout Islamic communities".

The thrust of his speech was directed at Israel, India, and the US, but also made a veiled reference to Pakistan's nuclear program:

"The US and the West are no longer the unquestionable decision-makers of the Middle East that they were two decades ago. Contrary to the situation 20 years ago, nuclear know-how and other complex technologies are no longer considered inaccessible daydreams for Muslim nations of the region."

He said the US was bogged down in Afghanistan and "is hated more than ever before in disaster-stricken Pakistan".

A former president of Iran (1981–89), Khamenei succeeded Ayatollah Khomeini as the spiritual head of the Iranian people. A staunch supporter of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Khamenei is believed to be highly influential in Iran's foreign policy.

Khamenei visited Jammu and Kashmir in the early 1980s and delivered a sermon at Srinagar's Jama Masjid mosque.

Atoms for Peace cooperation

Since 1987, Pakistan has steadily blocked any Iranian acquisition of nuclear weapons; however, Pakistan has wholeheartedly supported Iran's viewpoint on the issue of its nuclear energy program, maintaining that "Iran has the right to develop its nuclear program within the ambit of NPT." In 1987 Pakistan and Iran signed an agreement on civil nuclear energy cooperation, with Zia-ul-Haq personally visiting Iran as part of its "Atoms for Peace" program.[53] Internationally, Zia calculated that this cooperation with Iran was purely a "civil matter", necessary for maintaining good relations with Tehran.[53] According to IAEA, Iran wanted to purchase fuel-cycle technology from Pakistan, but was rebuffed.[53] Zia did not approve any further nuclear deals, but one of Pakistan's senior scientists did secretly hand over a sensitive report on centrifuges in 1987–89.[53] In 2005, IAEA evidence showed that Pakistani cooperation with Iran's nuclear program was limited to "non-military spheres",[54] and was peaceful in nature.[54] Tehran had offered as much as $5 billion for nuclear weapons technology in 1990, but had been firmly rejected. Centrifuge technology was transferred in 1989; since then, there have been no further atoms for peace agreements.[54]

In 2005, IAEA evidence revealed that the centrifuge designs transferred in 1989 were based on early commercial power plant technology, and were riddled with technical errors; the designs were not evidence of an active nuclear weapons program.[55]

Non-belligerent policy and official viewpoint

Difficulties have included disputes over trade, and political position. While Pakistan's foreign policy maintains balanced relations with Saudi Arabia, the United States, and the European Union, Iran tends to warn against it, and raised concerns about Pakistan's absolute backing of the Taliban during the fourth phase of civil war in Afghanistan in the last years of the 20th century.[8] Through a progressive reconciliation and chaotic diplomacy, both countries come closer to each other in last few years. In the changing security environment, Pakistan and Iran boosted their ties by maintaining the warmth in the relationship without taking into account the pressures from international actors.[56]

On Iran's nuclear program and its own relations with Iran, Pakistan adopted a policy of neutrality, and played a subsequent non-belligerent role in easing the tension in the region. Since 2006, Pakistan has been strategically advising Iran on multiple occasions to counter the international pressure on its nuclear program to subsequently work on civil nuclear power, instead of active nuclear weapons program.[57] On international front, Pakistan has been a great advocate for Iranian usage of nuclear energy for economics and civil infrastructure while it steadily stop any Iranian acquisition of nuclear weapons, fearing another nuclear armed race with Saudi Arabia.[58]

In a speech at Harvard University in 2010, the Pakistan's foreign minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi justified Iran's nuclear program as peaceful and argued that Iran had "no justification" to pursue nuclear weapons, citing the lack of any immediate threat to Iran, and urged Iran to "embrace overtures" from the United States. Qureshi also observed that Iran had signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and should respect the treaty.[59]

Trade and Economics

Relations between Iran and Pakistan improved after the removal of the Taliban in 2002, but tensions remain. Pakistan has been under a strong influence of Saudi Arabia in its competition with Shiite majority Iran for influence across the broader Islamic world, which it already has in its allied nations Lebanon and Syria. Iran considers northern and western Afghanistan as its sphere of influence since its population is Persian Dari speaking. Pakistan considers southern and eastern Afghanistan as its sphere of influence since it is Pashto and Baloch speaking such as the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan, respectively. Pakistan expressed concern over India's plan to build a highway linking the southern Afghanistan city of Kandahar to Zahidan, since it will reduce Afghanistan's dependence on Pakistan to the benefit of Iran.

Free Trade Agreement

In 2005, Iran and Pakistan had conducted US$500 million of trade. The land border at Taftan is the conduit for trade in electricity and oil. Iran is extending its railway network towards Taftan.

The Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline (IPI Pipeline) is currently under discussion; though India backed out from the project. The Indian government was under pressure by the United States against the IPI pipeline project, and appears to have heeded American policy after India and the United States proceeded to sign the nuclear deal. In addition, the international sanctions on Iran due to its controversial nuclear program could also become a factor in derailing IPI pipeline project altogether.

Trade between the two countries has increased by £1.4 billion in 2009.[60] In 2007-08, annual Pakistan merchandise trade with Iran consisted of $256 million in imports and $218.6 million in export, according to WTO.[61]

Bilateral trade

On 12 January 2001, Pakistan and Iran formed a "Pakistan-Iran Joint Business Council" (PIJB) body on trade disputes.[62] The body works on to encourage the privatization in Pakistan and economic liberalization on both sides of the countries.[62] In 2012, the bilateral trade exceeded $3 billion.[63] Official figures from the State Bank of Pakistan for fiscal year 2011-12 indicate imports of $124 million and exports of $131 million, which had collapsed to $36 million of exports to Iran and less than $1 million of imports for the year to April 2015. In 2011, the trade between Iran and Pakistan stood at less than $1 billion and the common geographical borders as well as religious affinities are among other factors, which give impetus to enhanced level of trade.[63] According to the media reports, Iran is the second-largest market of Basmati rice of Pakistan, ranking after Iraq.[64]

Effects of US sanctions on Iran

The U.S. economic sanctions on Iran regarding their nuclear program generally effected Pakistan's industrial sector.[65] The fruit industry of Pakistan have reportedly lost a lucrative market in Iran, where at least 30,000 tons of mango were exported previously, as a result of the trade embargo imposed by the United Nations on Tehran.[65] According to the statistics by Pakistan, the fruit industry and the exporters could not export around $10 million worth of mango during the current season.[65] The Ministry of Commerce (MoCom) has been in direct contact with the US Department of Agriculture to resolve the issue through diplomatic channels.[65]

Energy

Iran–Pakistan gas pipeline

Discussions between the governments of Iran and Pakistan started in 1994 for the gas pipelines and energy security.[66] A preliminary agreement was signed in 1995 by Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, in which, this agreement foresaw construction of a pipeline from South–North Pars gas field to Karachi in Pakistan. Later, Iran made a proposal to extend the pipeline from Pakistan into India. In February 1999, a preliminary agreement between Iran and India was signed.[67]

Iran has the world's second largest gas reserves, after Russia, but has been trying to develop its oil and gas resources for years, due to sanctions by the West. However, the project could not take off due to different political reasons, including the new gas discoveries in Miano, Sawan and Zamzama gas fields of Pakistan. The Indian concerns on pipeline security and Iranian indecisiveness on different issues, especially prices. The Iran-Pakistan-India (denoted as IPI Pipeline) project was planned in 1995 and after almost 15 years India finally decided to quit the project in 2008 despite severe energy crises in that country.

In February 2007, India and Pakistan agreed to pay Iran US$4.93 per million BTUs (US$4.67/GJ) but some details relating to price adjustment remained open to further negotiation.[68] Since 2008, Pakistan began facing severe criticism from the United States over any kind of energy deal with Iran. Despite delaying for years the negotiations over the IPI gas pipeline project, Pakistan and Iran have finally signed the initial agreement in Tehran in 2009. The project, termed as the peace pipeline by officials from both the countries, was signed by President Zardari and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran. In 2009, India withdrew from the project over pricing and security issues, and after signing another civilian nuclear deal with the United States in 2008.[69][70] However, in March 2010 India called on Pakistan and Iran for trilateral talks to be held in May 2010 in Tehran.[71]

According to the initial design of the project, the 2,700 km long pipeline was to cover around 1,100 km in Iran, 1,000 km in Pakistan and around 600 km in India, and the size of the pipeline was estimated to be 56 inches in diameter. However, as India withdrew from the project the size of the pipeline was reduced to 42 inch. In April 2008, Iran expressed interest in the People's Republic of China's participation in the project.[72]

Since as early as in 2005, China and Pakistan are already working on a proposal for laying a trans-Himalayan pipeline to carry Middle Eastern crude oil to western China.[73] Beijing has been pursuing Tehran and Islamabad for its participation in the pipeline project and willing to sign a bilateral agreement with Iran.China and Pakistan are already working on a proposal for laying a trans-Himalayan pipeline to carry Middle Eastern crude oil to western China.[73] In August 2010, Iran invited Bangladesh to join the project.[74]

Power Transmissions

Tehran has provided €50 million for laying of 170Km transmission line for the import of 1000MW of electricity from Iran in 2009. Pakistan is already importing 34MW of electricity daily from Iran. The imported electricity is much cheaper than the electricity produced by the Independent Power Producers (IPPs) because Iran subsidises oil and gas which feed the power plants.[75] Iran has also offered to construct a motorway between Iran and Pakistan connecting the two countries.[76]

Diplomacy and role in mediation

Since Iran has no diplomatic relations with the United States; the Iranian interests section in the United States is represented by the Embassy of Pakistan Embassy in Washington. Iranian nuclear scientist, Shahram Amiri, thought to have been abducted by CIA from Saudi Arabia, took sanctuary in the Pakistan Embassy in Washington, D.C. The Iranian government claimed the United States has trumped up charges they were involved with the 9/11 attacks.[77]

Diplomatic missions

Iranian missions in Pakistan

Iran's chief diplomatic mission to Pakistan is the Iranian Embassy in Islamabad. The embassy is further supported by many Consulates located throughout in Pakistan.[78] The Iranian government supports Consulates in several major Pakistan's cities including: Karachi‡, Lahore‡, Quetta‡, Peshawar‡.[78] Iranian government maintains a cultural consulate-general, Persian Research Center, and Sada-o-Sima center, all in Islamabad.[78] Other political offices includes cultural centers in Lahore†, Karachi†, Rawalpindi†, Peshawar†, Quetta†, Hyderabad†, and Multan†.[78]

- ‡ denotes mission is Consulate General

- † denotes mission is Khana-e-Farhang (lit. culture center)

There is also an Iran Air corporate office located in Karachi Metropolitan Corporation site.[78]

Immigration

In the Balochistan region of southeastern Iran and western Pakistan, the Balochi people routinely travel the area with little regard for the official border, causing considerable problems for the Iranian Guards Corps and the Frontier Corps of Pakistan. Both countries have ongoing conflicts with Balochi separatist groups.

Since 2010, there has been an increase in meetings between senior figures of both governments as they attempt to find a regional solution to the Afghan war and continue discussions on a proposed Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline and an Economic Cooperation Organization.[79]

Iranian media delegations have been visiting Pakistan annually since 2004, with many journalists settling in Pakistan. These visits have played an effective role in promoting mutual understanding and projecting a positive image of Pakistan in Iran.[80]

Notable Pakistani political figures Benazir, Murtaza, and Shahnawaz Bhutto were half Kurdish-Iranian on their mother's side.

Pakistan missions in Iran

Pakistan's chief diplomatic mission to Iran is the Pakistan Embassy in Tehran. It is further supported by two consulates-general located throughout in Iran.[81] The Pakistan government supports its consulates in Mashhad and Zahidan.[81]

Education

Pakistan International School and College Tehran serves Pakistani families living in Tehran.

See also

- Nuclear program of Iran

- Persian and Urdu

- Pakistan Armed Forces— Iranian Contingent

- List of statistically superlative countries

- Iran-Saudi Arabia proxy conflict

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Officials. "Pak-Iran Relations Since Islamic Revolution: Genisis of Cooperation and Competition". Embassy of Iran, Islamabad. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 et. al. "1971 war and Iran". 1971 war and Iran. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 Alvi, Ahmad Hasan (28 April 2001). "Chief Executive calls for stronger defence ties with Iran". Dawn News. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ http://www.dawn.com/news/1285404

- ↑ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Iran-keen-to-become-part-of-China-Pak-Economic-Corridor/articleshow/54462795.cms

- ↑ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Iran-keen-to-become-part-of-China-Pak-Economic-Corridor/articleshow/54462795.cms

- ↑ Max Fisher (11 January 2013). "Iran is popular in Pakistan, overwhelmingly disliked everywhere else". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Pant, Harsh V. (Spring 2009). "Pakistan and Iran's Dysfunctional Relationship". Middle East Quarterly. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Alam, Shah (20 December 2004). "Iran–Pakistan Relations: Political and Strategic Dimensions" (google docs.). Strategic Analysis. © The Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. 28 (4): 20. doi:10.1080/09700160408450157. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ↑ Foreign Policy Centre, "On the Margins of History", (2008), p.35

- 1 2 3 "Pakistan risks new battlefront". BBC News. 17 January 2005. Retrieved 8 April 2006.

- ↑ "BBC - Panorama - Iran Archives: Oil Barrels and the Gun". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shah, Mehtab Ali (1997). The Foreign Policy of Pakistan: Ethnic Impacts on Diplomacy, 1971–1994. London [u.a.]: Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-169-5.

- 1 2 3 Hanif, Muhammad. "Pakistan-Iran relations: Future challenges" (PDF). Islamabad Policy Research Institute. Muhammad Hanif, IPRI. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ Haq, Noor-ul-. "Iran Pakistan relations" (PDF). Benazir Bhutto in Iran (Press Release). Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ See: Chagai-I

- ↑ "NTI: Research Library: Country Profiles: Pakistan". NTI publications. Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ "Pakistan and the World (Chronology: October-December 1997)". Pakistan Horizon. Pakistan Institute of International Affairs. 51 (1): 73–90. January 1998. JSTOR 41394647.

- ↑ "Pakistani military ruler meets Iran's Khatami". The Iranian Times. Reuters. 9 December 1999. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iran wants end to sectarian violence in Pakistan". Afghanistan News Center. Reuters. 9 December 1999. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Musharraf leaves for Bahrain, Iran today, Pleads Pak-Iran joint efforts for Afghan peace". Afghanistan News Center. NNI. 8 December 1999. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Saba, Sadeq (8 December 1999). "Musharraf on goodwill mission". BBC. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iran & Pakistan to "coordinate" their policies towards Afghanistan". The Iranian Times. AFP. 9 December 1999. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iran, Pakistan to "coordinate" their policies towards Afghanistan". Afghanistan News Center. AFP. 9 December 1999. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iranian and Pakistani joint military operation against the Baloch, Kulber Valey, August 19, 2009". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ "Pakistan, Iran to promote reconciliation in Afghanistan". Afghanistan News Center. Kyodo. 27 April 2001. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Hussain, Talat (29 November 2001). "Pakistan, Iran seek to settle Afghan differences". CNN. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ M. Ziauddin; Faraz Hashmi (30 November 2001). "Kharrazi links peace to broad-based govt". Dawn. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Staff Reporter (1 December 2001). "Pakistan, Iran agree to lay gas pipeline: Trade ties being cemented". Dawn. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Iqbal, Nadeem (6 December 2001). "Pakistan, Iran Mend Fences over Afghanistan". IPS. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- 1 2 APP (11 March 2003). "Weapons found during Khatami visit". CNN. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Muir, Jim (23 December 2002). "Iran and Pakistan: A new beginning". BBC. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Akhlaque, Qudssia (23 December 2002). "Khatami visit a turning point". Dawn. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Zehra, Nasim (23 December 2002). "Khatami's visit may add a new dimension to Pakistan ties". Arab News. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Khatami visit to push South Asia pipeline project". CNN. 23 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iran seeks to boost Pakistan ties". BBC. 24 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Economic ties top priority, says Khatami". Dawn. APP. 24 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iran and Pakistan boost ties". BBC. 25 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ ul Haque, Ihtasham (25 December 2002). "Resolution of Kashmir issue soon: Khatami". DAWN. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Four accords signed with Iran". Dawn. APP. 25 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Iranian president lauds Iqbal's poetry". Dawn. APP. 25 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Hanif, Intikhab (27 December 2002). "Khatami concerned at atrocities in Kashmir". Dawn. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Khatami calls for talks on Kashmir". Arab News. 26 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Staff Reporter (27 December 2002). "Iran calls for better strategic relations: Joint communique". Dawn. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Khatami terms visit fruitful". Dawn. PPI. 27 December 2002. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Jamali talks trade with Khatami". Daily Times. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Shaukat Paracha (16 October 2003). "amali to discuss growing Indo-Iran ties with Khatami". Daily Times. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Rubin, Barry (1980). Paved With Good Intentions. Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-19-502805-8.

- 1 2 Minaham, James (2002). "The Dravidians: Baloch". Encyclopedia of the stateless nations : ethnic and national groups around the world. Westport (Connecticut): Greenwood Press. p. google books. ISBN 0-313-31617-1. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ "Pakistan-Iran agree for joint Anti-Terrorist and Anti-Drug operations". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ "Mahazi Islami - News & Events". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ "Khamenehi says Kashmir oppressed". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "A.Q. Khan and onward proliferation from Pakistan". The International Institute For Strategic Studies (IISS).

- 1 2 3 Hussain, Zahid (2008). Frontline Pakistan The Struggle With Militant Islam. Berkeley, Calif.: Columbia Univ Pr. ISBN 978-0-231-14225-0.

- ↑ Linzer, Dafna (23 August 2005). "No Proof Found of Iran Arms Program; Uranium Traced to Pakistani Equipment". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ http://www.opinion-maker.org/2012/03/pak-iran-relations-the-changing-scenario/

- ↑ "2006: Shaukat Aziz told Ahmedinejad to abandon Iran's nuclear weapons program". Dawn News. 9 July 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ "Pakistan supports peaceful use of Nuclear energy by Iran: PM Gilani". Geo Pakistan. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Iran doesn't need nuclear weapons: Qureshi". International Herald Tribune. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Iranian Embassy (18 February 2012). "Pak-Iran economic relations". The Nation, 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ WTO. "Iran's Economic Partner" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- 1 2 Reporter (13 January 2001). "Pakistan, Iran form body on trade disputes". Dawn Archives, 2001. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- 1 2 Staff Report (10 October 2012). "Pakistan to consider barter trade with Iran". Daily Pakistan 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ Staff Report (29 July 2012). "Pakistan to consider barter trade with Iran". Daily Pakistan 29 July. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Our Correspondents (5 January 2013). "Pakistan loses Iran's mango market". Tribune Express. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ "IPI Implementation Nearing 'Final Stage' – Pakistani Official". Downstream Today. Xinhua News Agency. 8 May 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ↑ Chaudhary, Shamila N. "Iran to India Natural Gas Pipeline: Implications for Conflict Resolution & Regionalism in India, Iran, and Pakistan". School of International Service. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ↑ "Peace Pipeline Contract Soon, Gas Flow by 2011". Iran Daily. 1 July 2007. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ↑ Haider, Zeeshan (17 March 2010). "Pakistan, Iran sign deal on natural gas pipeline". Reuters. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ↑ "Pakistan gas pipeline is Iran's lifeline". UPI. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ↑ "New Delhi calls for IPI talks". UPI. 19 March 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ↑ "Ahmadinehjad Would Welcome Chinese Role In Gas Pipeline". Xinhua News Agency. Downstream Today. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- 1 2 "DailyTimes - Your Right To Know". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ Kabir, Humayan (15 August 2010). "Iran invites Bangladesh to join cross-border gas grid". The Financial Express. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ Archived 8 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 17 August 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ "Iranian scientist surfaces in US – Americas". Al Jazeera. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Iranian presence in Pakistan". Consulate-Generals of Iran in Pakistan. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Staff reporter, w (12 December 2011). "Container Train line". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ . Khalid Aziz Babar , Ambassador of Pakistan to Tehran. "Cultural relations of Pakistan and Iran". Pakistan Embassy, Tehran. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Embassy of Pakistan in Iran". Embassy of Pakistan Presence. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of Iran and Pakistan. |

- Asia Times on Iran-Pakistan relations

- Schoresch Davoodi & Adama Sow: The Political Crisis of Pakistan in 2007 – EPU Research Papers: Issue 08/07, Stadtschlaining 2007 – Research Paper which also describes the relations between Pakistan and Iran

- Pakistan, Iran to boost cooperation in power sector

- Pattanayak, Dr. Satyanarayan : Iran's Relations with Pakistan: A Strategic Analysis – USI Research Book, May 2012 – A well researched book focuses on various facets of the Iran Pakistan relationship in a long term perspective by analyzing them under various Phases.