Partition of a set

In mathematics, a partition of a set is a grouping of the set's elements into non-empty subsets, in such a way that every element is included in one and only one of the subsets.

Definition

A partition of a set X is a set of nonempty subsets of X such that every element x in X is in exactly one of these subsets[2] (i.e., X is a disjoint union of the subsets).

Equivalently, a family of sets P is a partition of X if and only if all of the following conditions hold:[3]

- P does not contain the empty set.

- The union of the sets in P is equal to X. (The sets in P are said to cover X.)

- The intersection of any two distinct sets in P is empty. (We say the elements of P are pairwise disjoint.)

In mathematical notation, these conditions can be represented as

- if and then ,

where is the empty set.

The sets in P are called the blocks, parts or cells of the partition.[4]

The rank of P is |X| − |P|, if X is finite.

Examples

- Every singleton set {x} has exactly one partition, namely { {x} }.

- The empty set has exactly one partition, namely .

- For any nonempty set X, P = {X} is a partition of X, called the trivial partition.

- For any non-empty proper subset A of a set U, the set A together with its complement form a partition of U, namely, {A, U−A}.

- The set { 1, 2, 3 } has these five partitions:

- { {1}, {2}, {3} }, sometimes written 1|2|3.

- { {1, 2}, {3} }, or 12|3.

- { {1, 3}, {2} }, or 13|2.

- { {1}, {2, 3} }, or 1|23.

- { {1, 2, 3} }, or 123 (in contexts where there will be no confusion with the number).

- The following are not partitions of { 1, 2, 3 }:

- { {}, {1, 3}, {2} } is not a partition (of any set) because one of its elements is the empty set.

- { {1, 2}, {2, 3} } is not a partition (of any set) because the element 2 is contained in more than one block.

- { {1}, {2} } is not a partition of {1, 2, 3} because none of its blocks contains 3; however, it is a partition of {1, 2}.

Partitions and equivalence relations

For any equivalence relation on a set X, the set of its equivalence classes is a partition of X. Conversely, from any partition P of X, we can define an equivalence relation on X by setting x ~ y precisely when x and y are in the same part in P. Thus the notions of equivalence relation and partition are essentially equivalent.[5]

The axiom of choice guarantees for any partition of a set X the existence of a subset of X containing exactly one element from each part of the partition. This implies that given an equivalence relation on a set one can select a canonical representative element from every equivalence class.

Refinement of partitions

A partition α of a set X is a refinement of a partition ρ of X—and we say that α is finer than ρ and that ρ is coarser than α—if every element of α is a subset of some element of ρ. Informally, this means that α is a further fragmentation of ρ. In that case, it is written that α ≤ ρ.

This finer-than relation on the set of partitions of X is a partial order (so the notation "≤" is appropriate). Each set of elements has a least upper bound and a greatest lower bound, so that it forms a lattice, and more specifically (for partitions of a finite set) it is a geometric lattice.[6] The partition lattice of a 4-element set has 15 elements and is depicted in the Hasse diagram on the left.

Based on the cryptomorphism between geometric lattices and matroids, this lattice of partitions of a finite set corresponds to a matroid in which the base set of the matroid consists of the atoms of the lattice, namely, the partitions with singleton sets and one two-element set. These atomic partitions correspond one-for-one with the edges of a complete graph. The matroid closure of a set of atomic partitions is the finest common coarsening of them all; in graph-theoretic terms, it is the partition of the vertices of the complete graph into the connected components of the subgraph formed by the given set of edges. In this way, the lattice of partitions corresponds to the graphic matroid of the complete graph.

Another example illustrates the refining of partitions from the perspective of equivalence relations. If D is the set of cards in a standard 52-card deck, the same-color-as relation on D – which can be denoted ~C – has two equivalence classes: the sets {red cards} and {black cards}. The 2-part partition corresponding to ~C has a refinement that yields the same-suit-as relation ~S, which has the four equivalence classes {spades}, {diamonds}, {hearts}, and {clubs}.

Noncrossing partitions

A partition of the set N = {1, 2, ..., n} with corresponding equivalence relation ~ is noncrossing provided that for any two 'cells' C1 and C2, either all the elements in C1 are < than all the elements in C2 or they are all > than all the elements in C2. In other words: given distinct numbers a, b, c in N, with a < b < c, if a ~ c (they both are in a cell called C), it follows that also a ~ b and b ~ c, that is b is also in C. The lattice of noncrossing partitions of a finite set has recently taken on importance because of its role in free probability theory. These form a subset of the lattice of all partitions, but not a sublattice, since the join operations of the two lattices do not agree.

Counting partitions

The total number of partitions of an n-element set is the Bell number Bn. The first several Bell numbers are B0 = 1, B1 = 1, B2 = 2, B3 = 5, B4 = 15, B5 = 52, and B6 = 203 (sequence A000110 in the OEIS). Bell numbers satisfy the recursion

and have the exponential generating function

The Bell numbers may also be computed using the Bell triangle in which the first value in each row is copied from the end of the previous row, and subsequent values are computed by adding two numbers, the number to the left and the number to the above left of the position. The Bell numbers are repeated along both sides of this triangle. The numbers within the triangle count partitions in which a given element is the largest singleton.

The number of partitions of an n-element set into exactly k nonempty parts is the Stirling number of the second kind S(n, k).

The number of noncrossing partitions of an n-element set is the Catalan number Cn, given by

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Set partitions. |

- Exact cover

- Cluster analysis

- Weak ordering (ordered set partition)

- Equivalence relation

- Partial equivalence relation

- Partition refinement

- List of partition topics

- Lamination (topology)

-

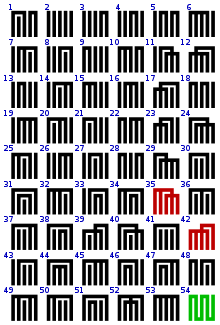

Rhyme schemes by set partition

Rhyme schemes by set partition

Notes

- ↑ Knuth, Donald E. (2013), "Two thousand years of combinatorics", in Wilson, Robin; Watkins, John J., Combinatorics: Ancient and Modern, Oxford University Press, pp. 7–37

- ↑ Naive Set Theory (1960). Halmos, Paul R. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 9780387900926.

- ↑ Lucas, John F. (1990). Introduction to Abstract Mathematics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 187. ISBN 9780912675732.

- ↑ Brualdi, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Schechter, p. 54

- ↑ Birkhoff, Garrett (1995), Lattice Theory, Colloquium Publications, 25 (3rd ed.), American Mathematical Society, p. 95, ISBN 9780821810255.

References

- Brualdi, Richard A. (2004). Introductory Combinatorics (4th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-100119-1.

- Schechter, Eric (1997). Handbook of Analysis and Its Foundations. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-622760-8.