Pedro Nunes

| Pedro Nunes | |

|---|---|

Pedro Nunes, 1843 print | |

| Born |

January 7, 1502 Alcácer do Sal, Portugal |

| Died |

August 11, 1578 (aged 76) Coimbra, Portugal |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Occupation | Mathematician, cosmographer, and professor |

Pedro Nunes (Portuguese: [ˈpedɾu ˈnunɨʃ]; Latin: Petrus Nonius; 11 January 1502 – 11 August 1578) was a Portuguese mathematician, cosmographer, and professor, from a New Christian (of Jewish origin) family.[1][2]

Nunes, considered to be one of the greatest mathematicians of his time,[3] is best known for his contributions in the nautical sciences (navigation and cartography), which he approached, for the first time, in a mathematical way. He was the first to propose the idea of a loxodrome and was also the inventor of several measuring devices, including the nonius (from which Vernier scale was derived), named after his Latin surname.[4]

Life

Little is known about Nunes' early education life or family background, only that he was born in Alcácer do Sal, his origins are Jewish and that his grandchildren spent a few years behind bars after they were accused by the Portuguese Inquisition of professing and secretly practicing Judaism.[5] He studied at the University of Salamanca, maybe from 1521 until 1522, and at the University of Lisbon (this University later become the University of Coimbra) where he obtained a degree in medicine in 1525. In the 16th century medicine used astrology, so he also learned astronomy and mathematics.[4]

He continued his medical studies but held various teaching posts within the University of Lisbon, including Moral, Philosophy, Logic and Metaphysics. When, in 1537, the Portuguese University located in Lisbon returned to Coimbra, he moved to the re-founded University of Coimbra to teach mathematics, a post he held until 1562. This was a new post in the University of Coimbra and it was established to provide instruction in the technical requirements for navigation: clearly a topic of great importance in Portugal at this period, when the control of sea trade was the primary source of Portuguese wealth. Mathematics became an independent post in 1544.[4]

In addition to teaching he was appointed Royal Cosmographer in 1529 and Chief Royal Cosmographer in 1547: a post which he held until his death.[4]

In 1531, King John III of Portugal charged Nunes with the education of his younger brothers Luís and Henry. Years later Nunes was also charged with the education of the king's grandson, and future king, Sebastian.[4]

While at the University of Coimbra, Christopher Clavius attended Pedro Nunes' classes, and was influenced by his works.[4] Clavius, the greatest figure of the Colégio Romano, the great centre of catholic knowledge of that period, classified Nunes as “supreme mathematical genius".[5] Nunes died in Coimbra.

Work

Pedro Nunes lived in a transition period, during which science was changing from valuing theoretical knowledge (which defined the main role of a scientist/mathematician as commenting on previous authors), to providing experimental data, both as a source of information and as a method of confirming theories. Nunes was, above all, one of the last great commentators,[6] as is shown by his first published work “Tratado da Esfera”, enriched with comments and additions that denote a profound knowledge of the difficult cosmography of the period.[5] He also acknowledged the value of experimentation.

In his Tratado da sphera he argued for a common and universal diffusion of knowledge.[7] Accordingly, he not only published works in Latin, at that time science's lingua franca, aiming for an audience of European scholars, but also in Portuguese, and Spanish (Livro de Algebra).

Navigation

Much of Nunes' work related to navigation. He was the first to understand why a ship maintaining a steady course would not travel along a great circle, the shortest path between two points on Earth, but would instead follow a spiral course, called a loxodrome.[5] The later invention of logarithms allowed Leibniz to establish algebraic equations for the loxodrome.[8] These lines —also called rhumb lines— maintain a fixed angle with the meridians. In other words, loxodromic curves are directly related to the construction of the Nunes connection —also called navigator connection.[9]

In his Treaty defending the sea chart, Nunes argued that a nautical chart should have its parallels and meridians shown as straight lines. Yet he was unsure how to solve the problems that this caused: a situation that lasted until Mercator developed the projection bearing his name. The Mercator Projection is the system which is still used.

Geometry

Nunes also solved the problem of finding the day with the shortest twilight duration, for any given position, and its duration.[5] This problem per se is not greatly important, yet it shows the geometric genius of Nunes as it was a problem which was independently tackled by Johann and Jakob Bernoulli more than a century later with less success.[10] They could find a solution to the problem of the shortest day, but failed to determine its duration, possibly because they got lost in the details of differential calculus which, at that time, had only recently been developed. The achievement also shows that Nunes was a pioneer in solving maxima and minima problems, which became a common requirement only in the next century using differential calculus.[11]

Cosmology

He was probably the last major mathematician to make relevant improvements to the ptolemaic system (a geocentric model describing the relative motion of the Earth and Sun). However, this lost importance because Copernicus introduced his heliocentric system theory around the same time. Nunes knew Copernicus' work but referred only briefly to it in his published works, with the purpose of correcting some mathematical errors.

Most of Nunes' achievements were possible because of his profound understanding of spherical trigonometry and his ability to transpose Ptolemy's adaptations of Euclidean geometry to it.

Inventions

Nunes worked on several practical nautical problems concerning course correction as well as attempting to develop more accurate devices to determine a ship's position.[11]

He created the nonius to improve the astrolabe's accuracy. This consisted of a number of concentric circles traced on the astrolabe and dividing each successive one with one fewer divisions than the adjacent outer circle. Thus the outermost quadrant would comprise 90° in 90 equal divisions, the next inner would have 89 divisions, the next 88 and so on. When an angle was measured, the circle and the division on which the alidade fell was noted. A table was then consulted to provide the exact measure.

The nonius was used by Tycho Brahe, who considered it too complex. The method inspired improved systems by Christopher Clavius and Jacob Curtius.[12] These were eventually improved further by Pierre Vernier in 1631, which reduced the nonius to Vernier scale that include two scales, one of them fixed and the other movable. Vernier himself used to say that his invention was a perfected nonius and for a long time it was known as the “nonius”, even in France.[5] In some languages, the Vernier scale is still named after Nunes, for example nonieskala in Swedish.

Pedro Nunes also worked on some mechanics problems, from a mathematical point of view.

Influence

Nunes was very influential internationally e.g. on the work of John Dee and Edward Wright.[13]

Honours

- One of the best known Lisbon public Secondary/High Schools is named after Pedro Nunes, Escola Secundária de Pedro Nunes (teaching 7th to 12th grade). It was founded, in 1906, as Lyceu Central da 3ª Zona Escolar de Lisboa (Central Liceum of the 3rd School Area of Lisbon). Over the years had known several designations: Lyceu Central de Pedro Nunes (1911–1930), Liceu Normal de Lisboa (1930–1937), Liceu Pedro Nunes (1937–1956), Liceu Normal de Pedro Nunes (1956–1978) and Escola Secundária de Pedro Nunes (1978–As of 2011), but is still popularly known as Liceu Pedro Nunes. Many well known Portuguese personalities have studied in Pedro Nunes. The current headquarters commemorated its centenary in 2011, after being totally refurbished and modernized between 2008 and 2010.

- He was featured on 100 escudos coins.

- The Instituto Pedro Nunes in Coimbra, a business incubator and a center of innovation and technology transfer founded by the University of Coimbra, is named after Pedro Nunes.

- Asteroid 5313 Nunes is named after him

Bibliography

Pedro Nunes translated, commented and expanded some of the major works in his field, and he also published original research.

Commented and expanded translations:

- Tratado da sphera com a Theorica do Sol e da Lua (Treaty about the Sphere with Theory of the Sun and the Moon), (1537). From Tractatus de Sphaera by Johannes de Sacrobosco, Theoricae novae planetarum by Georg Purbach and the Geography by Claudius Ptolemaeus.

Original work:

- Tratado em defensam da carta de marear (Treatise Defending the Sea Chart), (1537).

- Tratado sobre certas dúvidas da navegação (Treatise about some Navigational Doubts), (1537)

- De crepusculis (About the Twilight), (1542).

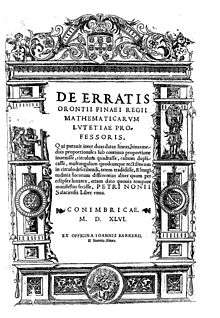

- De erratis Orontii Finei (About the Errors of Orontii Finei), (1546).

- Petri Nonii Salaciensis Opera, (1566). Expanded, corrected and reedited as De arte adque ratione navigandi in 1573.

- Livro de algebra en arithmetica y geometria (Book of Algebra in Arithmetics and Geometry), (1567).

Some modern reprints:

- Obras (6 vol.), Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, Lisboa, 1940-1960 (No ISBN at the books' record at the Portuguese National Library)

- Obras (3 vol.), Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa, 2002-?, ISBN 972-31-0985-9 and ISBN 972-31-1084-9 (more volumes are likely to be published)

Notes

- ↑ Martins, Jorge, Portugal e os Judeus (3 vol.), Nova Vega, Lisboa, 2006, ISBN 972-699-847-6

- ↑ J J O'Connor (November 2010). "Pedro Nunes Salaciense". Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ↑ Pedro Nunes (1502-1578)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (November 2010). "Biography of Pedro Nunes Salaciense". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pedro Nunes – A mathematician in a country of navigators

- ↑ Fernández, V.V.; Rodrigues Jr.,, W.A., (2010), Gravitation as a Plastic Distortion of the Lorentz Vacuum, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, p. 5, ISBN 978-3-642-13589-7

- ↑ «o bem, quanto mais comum e universal, tanto é mais excelente» quoted by Calafate, Pedro (see above)

- ↑ Science in the Spanish and Portuguese empires, 1500-1800

- ↑ In mathematics, Nunes connection is an example of connection which Cartan showed to Einstein in 1922 when he visited Paris.

- ↑ Prelúdio para uma história: ciência e tecnologia no Brasil

- 1 2 Pedro Nunes (1502 - 1578)(Science)

- ↑ Daumas Maurice, Scientific Instruments of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries and Their Makers, Portman Books, London 1989 ISBN 978-0-7134-0727-3

- ↑ Almeida, Bruno & Leitão, Henrique (2009). "Edward Wright and Pedro Nunes". Pedro Nunes (1502 - 1578). Centre for the History of Sciences, Lisbon University. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

References

- Mourão, Ronaldo Rogério de Freitas, Dicionário das Descobertas, Pergaminho, Lisboa, 2001, ISBN 972-711-402-4

- Dias, J. S. da Silva, Os descobrimentos e a problemática cultural do século XVI (3rd ed.), Presença, Lisboa, 1988

- Calafate, Pedro, Pedro Nunes, at Instituto Camões' site (in Portuguese)

- Printed works of Pedro Nunes in the 16th century, at Portuguese National Library (in Portuguese)