Pemmican War

| Pemmican War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Fight at Seven Oaks, June 19, 1816 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Selkirk's settlers | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Pemmican War was a series of armed confrontations during the North American fur trade between the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company (NWC) in the years following the establishment of the Red River Colony in 1812 by Lord Selkirk. It ended in 1821 when the NWC merged with the HBC.

Background

.jpg)

At the beginning of the 19th century, Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk attempted to resettle his fellow Scotsmen and women in North America. By 1808, Selkirk had founded two colonies, one on Prince Edward Island, another at Baldoon in Western Ontario, and was looking to establish a third. The eastern coastline of Canada was already settled and no longer had any tracts of land large enough to support a colony, so Selkirk looked for a location with good soil and a temperate climate far in the interior. He quickly discovered the region best fitting his needs fell within the territory of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). Selkirk began in 1808 buying shares of the HBC in order to acquire the land he needed. Because of the crippling competition with the North West Company (NWC), the HBC’s stock at this time was down from 250% to 50%, and he was able to buy a majority share equalling £100,000 (in comparison the whole of the HBC stock was worth about £150,000).

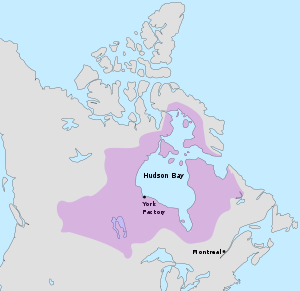

In May 1811 the HBC granted Selkirk 116,000 square miles of company territory which encompassed most of the Red River watershed.[1] Today this region is shared by Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, North and South Dakota and Minnesota. The region was already occupied at that time by numerous tribes of Native Americans and Métis, as well as containing outposts belonging to both the North West and Hudson's Bay companies. For 100 years the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company dominated the North American fur trade operating almost exclusively from their depots along the shores of Hudson Bay (though their charter, granted by Charles II in 1670 gave them exclusive rights to trade along the banks of any connected waterway), but competition from various Montréal merchants and later the North West Company in the 1770s changed this. The North West Company and others generally traded beyond the actual reach of the HBC, but generally still within their territory, easing the burden for natives of those regions to travel the long distance to Hudson Bay to trade. To compete with the North West Company, the HBC began expanding inland. In 1774 they built Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River delta and soon had outposts situated throughout the northwest, in some cases directly across from their adversaries, sparking a period of intense competition. The Red River region also contained the North West Company’s pivotal provisioning depots.

The pemmican trade

Unlike the Hudson’s Bay Company, which imported most of its provisions from England, the NWC relied heavily upon locally procured pemmican. Pemmican was made of dried buffalo meat pounded into a powder and mixed with melted buffalo fat in leather bags. To procure pemmican in sufficient quantities, the NWC traded for it at several outposts in the Red River District and transported it to their Bas de la Rivière depot on Lake Winnipeg where it was distributed to brigades of north canoes passing between Fort William and Athabasca or transported to Fort William where it was issued to brigades going to the company’s eastern and southern districts. The majority of the NWC’s pemmican was purchased from the local Métis and to a lesser degree from the local Indians and freemen.

The Métis were the descendants of European (mostly French-Canadian) fur traders and their native wives. By the early 1800s, the Métis had formed large communities and were in the process of creating their own unique identity. The particular Métis band around Red River was referred to as Bois-Brûlés or "burnt wood," which was a French translation of the Ojibwe word meaning "half-burnt woodsmen;" a name the Métis earned because their skin was generally lighter than that of the full-blooded Natives.[2]

The natives of the Red River district were primarily of the Saulteaux nation, known today as the northern or plains Ojibwa.[1] They traded with both the NWC and HBC and, despite frequent attempts by the NWC to pit them against its rival, remained neutral in the dispute between the fur companies. The Red River District was also home to a small community of retired NWC voyageurs, called "freemen" because they were free of their contracts with the company.

The Red River pemmican was absolutely vital to the NWC. Without it, the company could not adequately feed its employees. William McGillivray later swore in a court of law that the NWC could not function without it. The Nor’westers saw a HBC backed colony in the Red River as a direct threat to their existence. The NWC first protested directly to the HBC, hired lawyers to dispute the HBC’s charter, and even published anonymous articles in newspapers to dissuade prospective settlers by pointing out the hardships of the journey, the harshness of the land and stating that the settlers would all be massacred by Indians. However, despite the NWC’s best efforts, Selkirk’s colony was to proceed.

Selkirk's colony

In July 1811, Scottish and Irish settlers consisting of 25 families embarked aboard HBC and private ships led by the colony's appointed governor Miles Macdonell (whom the local Indians would later dub "chief of the gardeners"). Those colonists who could not afford their passage indentured themselves to the HBC. They brought with them everything they needed to build a colony, as well as arms to protect it from the Indians and Americans (Great Britain and the United States then being on the brink of war), consisting of 200 muskets, 4 brass 3-pound field pieces, 1 howitzer and 3 swivel guns courtesy of the British Colonial Department. In September the settlers arrived at York Factory and entered winter quarters there.[1]

Because of a lack of boats to transport Selkirk's settlers and their vast supplies, they spent the spring and part of the summer of 1812 building four wooden boats, finally departing in mid-summer. The settlers arrived in the fall at the colony site, located at a bend in the Red River about a half mile north of the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. The settlers built a fort along a small stream southwest of the colony, named Fort Douglas in honour of Lord Selkirk. The fort was to be shared by the settlers and HBC employees, and contained company store houses as well as the governor's house, often referred to as the "Government House." Settlers began constructing huts to see them through the winter, but the late season forced many of them to winter at nearby HBC posts. However, these posts had insufficient provisions to support the extra people and the settlers, though given provisions by the NWC, nearly starved.(p. 33)[3]

Additional settlers arrived at the colony in the spring of 1813 and the settlers finally began building proper houses and planting crops. The NWC's John Wills ordered John Pritchard to buy as much Red River pemmican as possible. Pritchard succeeded in buying a third more than usual.

Pemmican Proclamation

Provisions were scarce in the colony at the beginning of 1814. Governor Macdonell, in an attempt to prevent much needed provisions from leaving the district issued the “Pemmican Proclamation” on January 8. It read, in part:

“Whereas the welfare of the families at present forming settlement on the Red River, within the said territory, with those on their way to it…as also those who are expected to arrive next autumn, renders it a necessary and indispensable part of my duty to provide for their support. In the yet uncultivated state of the country, the ordinary resources derived from the buffalo and other wild animals hunted within the territory, are not deemed more than adequate for the requisite supply, wherefore it is hereby ordered, that no person trading in furs or provisions within the territory for the Honourable Hudson’s Bay Company, the North-West Company, or any individual, or unconnected trader or persons whatever, shall take out any provisions, either flesh, dried meat, grain, or vegetable.”[4]

Both North West and Hudson’s Bay companies formally protested the proclamation, but Lord Selkirk, being the majority shareholder of the HBC was able to deal with his company’s complaints through official channels. Special Commissioner Coltman, the government official later charged with investigating the Battle of Seven Oaks, suggested that Gov. Macdonell waited for an opportune moment to release his proclamation, the idea of which he had brought up some time earlier, and suggested that moment was the American victory at the Battle of Lake Erie which occurred September 10, 1813 which gave the Americans command of Lake Erie and threatened the NWC’s ability to transport goods, furs and provisions over the Great Lakes. Issuing the proclamation at this time therefore would have starved the Nor’westers out of the region. In fact, the Nor’Westers would later testify that the British loss of Lake Erie rendered the company more dependent on the Red River pemmican than ever. The NWC disregarded the proclamation and Gov. Macdonell was obliged to enforce it.

HBC blockades

On March 14, 1814 John Warren (who was a clerk in the colony) and 15 or 16 armed colonists travelled to the Métis hunting camp at Turtle River to acquire provisions. That night several NWC sleighs arrived to do the same, and Warren’s men forced them back empty handed. Shortly afterward, Gov. Macdonell, hearing that a NWC boat loaded with pemmican was being sent down the Assiniboine from Qu’Appelle, sent John Warren with a party of fifty men with two field pieces to seize it. The men had instructions to fire their muskets at any boat that passed and drive them ashore, and any that might refuse should be sunk by cannon fire. The colonists openly refused to obey the latter order, however. The NWC’s John Wills at Rivière la Souris, hearing of the blockade and not seeing the boat he expected, dispatched a party of six men to investigate, avoiding the blockade by taking the high-road around the river. Wills’ men found the boat crew encamped on the river shore and ordered them to cache the provisions in a hidden place. Seeing this party of armed Nor'Westers, the HBC battery obtained reinforcements. When the boat did not appear as expected, the Baymen searched for it and found the three Canadians encamped with an empty boat. Warren questioned them about their provisions and threatened to arrest them, but he received no response. After a search of one or two days, the cache of 96 bags of pemmican was discovered and taken to Ft. Douglas.(p. 31)[3] The HBC next blockaded the high-road the Nor’Westers used to circumvent the river blockade, which, besides disrupting the Nor’Wester’s use of the road, also would prevent the local natives and Métis from passing. One native family was taken prisoner. Upon learning this, the local Métis offered aid to the Nor’Westers for an attack on the HBC blockade, but the offer was declined.

On May 29, 1814 Governor Macdonell sent John Spencer, the colony’s sheriff, to seize provisions located at the NWC's Rivière la Souris post. He confiscated 500 bags of pemmican, 96 kegs of grease and 9 bales of dried meat.(p. 28)[3] He also confiscated two chests of NWC-owned guns to prevent them from being sold to the Métis and thus preventing them from hunting buffalo. Part of the confiscated provisions were taken across the river to Brandon House, while the rest was taken to Fort Douglas under an armed escort. Next, Macdonell’s men confiscated 200 bags of pemmican from a HBC trader named Stett who was transporting 300 bags to York Factory. Shortly afterward, the NWC’s Duncan Cameron took an armed party of voyageurs to locate and arrest an HBC trader named House who had helped break into the Rivière la Souris post. Governor Macdonell next built a battery on the Assiniboine River to more effectively command the river and another on the Red River near Fort Douglas. The Red River blockade soon captured two NWC light canoes with 2 clerks, 20 men and 2 chests of arms. The voyageurs were paroled, but the clerks and the chests of arms were sent to Fort Douglas.

On June 18, 1814 the NWC’s John Macdonald met with Governor Macdonell to work out a peace agreement. To try to prevent bloodshed and to help alleviate the general starvation of the NWC caused by Macdonell’s confiscation of all the Nor’Wester’s provisions, the men agreed that Governor Macdonell should keep 200 bags of pemmican and return the rest that had been seized. In exchange, the Nor’Westers would release Mr. House and supply the colony with provisions during the coming winter. It appears the terms were more or less followed. Commissioner Coltman later testified that the agreement was kept with "some little deviations."

That summer, during the general meeting at the North West Company’s annual rendezvous at Fort William, the partners discussed how to deal with the Red River problem. It was officially agreed that the Red River District needed to be re-enforced, that arrest warrants should be issued for John Spencer, John Warren and Miles Macdonell and that Selkirk’s colony should be reduced by offering the settlers free passage to Upper Canada. It was decided that partners Duncan Cameron and Alexander Macdonell (the cousin and brother-in-law of Gov. Miles Macdonell) should oversee the operation in the Red River District. Unofficially however, the partners plotted to attack the colony. This was to be done by first disarming it and then paying the Indians of Lac Rouge and Fond du Lac to destroy it. Of course, this plan was not recorded in the meeting notes, but there is an abundance of evidence to support it; for instance, Daniel Mackenzie, the officer in charge of the Fond du Lac District received a letter from Duncan Cameron in the spring of 1815 stating that he had orders to destroy the colony, and the chief of the Fond du Lac Indians later testified that Daniel Mackenzie offered him all the goods at Leech Lake, Sandy Lake and Lac la Pluie to “make war on the English,”[5] but he refused. The Nor’Westers only managed to recruit a handful of Natives, but they refused to attack the settlers once they arrived on the scene the following year. Within days of Duncan Cameron’s arrival at the Red River District in September he arrested sheriff John Spencer and sent him to the NWC’s Fort Gibraltar located south of the Red River colony. As the canoe that was conveying Spencer to Lac la Pluie passed Fort Douglas, several colonists broke into the arms locker to give them the weapons needed to mount a rescue. They drove the canoe ashore, but Spencer convinced the settlers not to kill the Nor’Westers and to let them carry out their duty. As Duncan Cameron appeared nearby again that evening, one colonist fired at him to no effect.

HBC invokes charter

In October, 1814 Governor Macdonell sent notes to the NWC outposts in the region in the name of Lord Selkirk ordering them to abandon their posts within six months. He then raised a company of volunteer militia from the Red River settlers, armed them with muskets and appointed himself as commander.[6] By doing so, Macdonell was invoking the rights of the Hudson’s Bay Company Royal Charter, which they felt the NWC was violating.[7]

Selkirk raises an army

In 1815, Selkirk was in Montreal raising men to defend his colony. He first petitioned the British government for regular infantry. In March, Lord Bathurst instructed the governor of Canada to "give such protection to the settlers on Red River as could be afforded without detriment to his Majesty’s services in other quarters."[8] However, British commanders were reluctant to send troops to Red River because of the difficulty in transporting them such long distances. Selkirk pointed out that the Nor’Westers annually sent large quantities of bulky goods hundreds of miles beyond the Red River. Selkirk was eventually granted a sergeant’s detachment of the 37th Regiment consisting of around 14 men commanded by Sergeant Pugh, not as an official military representative but to act as Selkirk’s personal guard. Selkirk next turned to the HBC. The HBC was allowed to raise armed forces for their protection under a clause in their charter. It stated:

“We do give and grant unto the said governor and company free liberty and license in case they conceive it necessary to send either ships of war, men or ammunition unto any of their plantations, forts or places of trade aforesaid for the security and defence of the same and to choose commanders and officer over them and to give them power and authority to continue or make peace or war with any prince or people whatsoever, that are not Christian in any place where the said company shall have any plantations, forts or factories.”[9]

Selkirk wrote to the King’s Attorney and Solicitor General informing them of his intentions to raise an army per the HBC charter and requested their approval, but no response was made. Thus, Selkirk raised a force consisting of 180 Hudson’s Bay Company employees and around 150 soldiers recently discharged from the De Meuron and De Watteville regiments. De Meuron’s and De Watteville’s were two Swiss regiments on the English establishment of the regular army and veterans of the Napoleonic Wars. These men, though no longer enlisted soldiers, still retained their military uniforms which consisted of light blue faced red coats, trousers and black felt shakos. Selkirk provided them with muskets, bayonets and cartridge pouches and paid them out of his own pocket.

The NWC gather troops

William McGillivray, hearing that Selkirk had obtained a contingent of regular soldiers also petitioned the government for his own soldiers that his company may not be discriminated against. He only managed to negotiate for two officers of De Meuron’s regiment to take a leave of absence for six months. Lieutenants Bromby and Missani departed Montreal for Fort William in spring of 1816. Being on leave of absence, these men were now common citizens with no military authority, but they continued to wear their military uniforms. McGillivray also recruited Charles De Reinhard, a discharged sergeant of De Meuron’s Regiment. In addition, those company partners formerly in the Corps of Voyageurs continued to act in the capacity of military officers. Duncan Cameron often signed his letters during this time as “Captain, Voyageur Corps.” The Voyageur Corps was a regiment raised by partners of the NWC and made up mostly of NWC voyageurs which fought in the War of 1812. In fact, the NWC may have continued issuing military commissions to their partners even after the regiment was disbanded on March 1, 1815. At Red River, Duncan Cameron acted in the capacity of a Captain with Alexander Macdonnel as his lieutenant and Seraphim Lamarre as his ensign. Likewise, Cuthbert Grant was perceived as a captain of the Métis, with William Shaw as his lieutenant and Peter Pangman as his ensign.[10]

At this time, the HBC sent one Colin Robertson to Montreal to raise a party to oppose the NWC in the Athabasca District. Posing as one of Lord Selkirk’s agents selling land in the Red River District, Robertson secretly raised a band of 160 voyageurs. They departed for Athabasca on May 17 in 16 canoes. In February the Métis set up a camp on the Turtle River plains and began harassing Red River settlers by stampeding the buffalo herds they were hunting. The Métis also detained Red River settler John Macleod for six days while he was conveying a message to them from Governor Macdonell. At the same time, Governor Macdonell arrested HBC defector Peter Pangman who was now working for the NWC, and later arrested Nor’Wester Hugh Heney for his role in detaining John Macleod. In retaliation, Métis leader Cuthbert Grant with a party of around 27 of his followers captured colonist John Warren and three others while travelling between Fort Daer and Turtle River. Fed-up, Governor Macdonell met with the Nor’Westers at Fort Pembina and successfully arranged a prisoner exchange.

Attacks on the colony and the burning of Fort Douglas

In 1815 NWC partner Duncan Cameron now began to implement the company’s plan to dislodge the Red River settlers. This was done primarily by threatening to unleash the Indians on the colony and offering the colonists free passage to Upper Canada.[11] Not every Nor’Wester in the Red River District was interested in the destruction of Selkirk’s colony. Around this time, the NWC clerk Aulay McAulay refused to sell firearms and ammunition to the Métis to use against the colony. Consequently, at the next rendezvous at Fort William, Aulay was not allowed to dine at the general mess-table, the other clerks were ordered not to associate with him, and he was sent back to Montreal aboard a loaded Montreal canoe as a sign of disgrace.

The Nor’Wester’s offers of free passage soon had the desired effect. Coupled with the harsh living conditions in the region, disgruntled settlers began leaving the colony. Archibald Macdonald, then in command of the colony while Gov. Macdonell was temporarily away, threatened to use the colony’s cannons to prevent their leaving. As a result, on April 3 a party of disgruntled settlers led by George Campbell detained the officers in the mess room of Fort Douglas, broke into the colony’s warehouses and stole a number of artillery pieces, weapons and tools, carrying them off on horse-drawn sleighs while the imprisoned officers watched through the mess-room windows. The colonists then met with Duncan Cameron and a party of NWC voyageurs to whom they gave the stolen guns. The unmounted guns were conveyed by canoes to Fort Gibraltar where field carriages were made for them. When Governor Macdonell returned, NWC officer Severight attempted to arrest him, but Macdonell resisted stating a legally appointed governor cannot be arrested and taken from his post. Macdonnel detained Severight for several hours and then released him.

Alexander Macdonnell’s force swelled in May with NWC employees passing between their wintering posts and Fort William and with local Métis, freemen and Cree from the north. The local Saulteaux arrived at the colony to help protect the settlers and stated that their presence would dissuade the Cree from attacking. However, the Saulteaux departed after 2 weeks upset at not being compensated for their assistance. Afterwards, 10 or 12 cows belonging to the colony were found riddled with arrows. It is unknown whether this was done by the Métis or the disgruntled Saulteaux. With his small army, Alexander Macdonnell finally began to take action against the Red River colony. Macdonnell, with a party of around 60 voyageurs and Métis established a camp at Frog Plain, 3 or 4 miles from Fort Douglas and erected a battery of 4 guns to prevent boats coming or going from the colony. It was provided with shot forged by the NWC blacksmith at Fort Gibraltar. On June 10 several colonists fired at a party of Métis conveying provisions to their camp at Frog Plain and a brief exchange of fire took place with no casualties. That same day a canoe arrived at Fort Gibraltar from Fort William announcing the end of the War of 1812 and proclaimed “peace with all the world except Red River.” Macdonnell’s men next made off with the colony’s cattle. Colonists Duncan McNaughton, Alexander Mclean and John McLeod, riding near Frog Plain, observed the stolen cattle. They attempted to drive them back to the colony and were themselves driven off by several shots from Macdonnel’s men. One John Early’s gun misfired and he apologized stating he surely would have killed McNaughton, as his gun was loaded with two balls.[12] The Métis now took matters into their own hands. Parties of Métis paraded in front of the Red River settlement day and night singing war songs to intimidate the settlers. Some settlers were abducted and their houses were dismantled or burned. Settlers continually deserted, often taking away arms and ammunition belonging to the colony. The Nor’Westers erected another battery with one piece opposite Fort Douglas. A breastwork was thrown up around it partially made from wood taken from dismantled houses. Duncan Cameron dispatched parties of armed men along various roads to capture any wandering settlers. In June, NWC forces attacked the colony no less than 4 times, often firing at the dwelling houses from hidden positions. In every case the colonists returned fire. Four colonists and Baymen were wounded by enemy fire and John Warren was nearly killed when his wall gun bursts. Eventually, the Métis entered the Red River colony and occupied several houses including that of John Pritchard which they set up as their headquarters. Several colonists were evicted and their houses burned. After the last attack on June 11 which lasted half an hour, the colonists met with Governor Macdonell and suggested that he surrender himself to end the violence. On June 15, the Nor’Westers attacked the Red River colony in force, taking a number of prisoners and throwing up a rampart with cannon around the grain store. They also let the colonists horses loose to trample their crops. The next day, the NWC’s Alexander Mackenzie and Simon Frazer arrived from Fort William and wrote to Governor Macdonell that if he surrendered himself the colony would be left in peace. Governor Miles Macdonell subsequently surrendered himself and made a verbal agreement with the NWC for the following terms:

- The Red River colony is to keep 200 bags of pemmican.

- The NWC will be allowed to transport that year’s provisions and furs through Hudson’s Bay (It should be noted that the NWC was already allowed to send their goods through Hudson’s Bay during this time as per an agreement with the HBC and British government in consequence of the War of 1812.)

- The NWC will provide the colony with 175 bags of pemmican or the equivalent in fresh or dried buffalo meat during the winter.

On June 22, Governor Macdonell departed a prisoner for Fort William. Later that day, the Métis resumed firing at the colonists. The HBC’s James Sutherland and one Mr. White met with the Métis at Frog Plain to negotiate a new peace settlement. Sutherland and White proposed that the colonists should abandon the colony and resettle in the woods a few miles below the forks and that both parties should live in peace. The Métis rejected this proposal. They finally agreed to the following terms:

- That all settlers retire immediately from the river, and no appearance of the colony is to remain.

- That peace and amity to subsist between all parties, traders, Indians and freemen in the future throughout the two rivers and on no account are persons to be molested in their lawful pursuits.

- The HBC will, as customary, enter the river with from 3 to 4 of their former boats and from 4 to 5 men per boat as usual to trade.

- Whatever former disturbances have taken place between both parties are to be totally forgotten and not to be recalled by either party.

- And every person retiring peaceably from the river immediately shall not be molested in their passage out.

The settlers agreed to these terms and fled by boat towards Jack River House (later renamed Norway House) under the guard of local Indians who offered to convey them as far as Lake Winnipeg. HBC trader John Mcleod and three men remained at the colony as representatives of the HBC and to maintain the colonists' crops.

On June 24, the Métis burned Fort Douglas and the colony's mill, stables and most of the empty houses. This was done by cutting open the windward side to allow the breeze to spread the flames. The goods and horses belonging to the colony were given to the Métis as gifts. The fleeing settlers stopped at Jack River House. While there they were met by Colin Robertson and his brigade bent for the Athabasca district. Robertson was convinced to stay and help re-establish the Red River Colony and dispatched a party of 100 men under John Clark to Athabasca to carry out his mission there. Robertson with the displaced settlers and around 20 HBC employees arrived at the ruins of Fort Douglas on August 19 and began rebuilding the fort.

On October 15, 1815 Duncan Cameron, the Nor’Wester in charge of Fort Gibraltar was captured while riding on the plains. While being interviewed by Colin Robertson, Cameron informed him that most of the arms stolen from the Red River Colony were being stored at his fort, though the stolen artillery was spread throughout the district. Therefore, Robertson sent 12 men under the command of Alexander McLean to capture Fort Gibraltar and retrieve the colony’s arms. Robertson returned Fort Gibraltar to Cameron after he signed an agreement ceasing all hostilities against the colony and promising to restore the stolen artillery. Fort Gibraltar was a mere half-mile from the Red River Colony and had been the staging point for the attack on the settlement. Robertson next attempted to take the NWC’s Fort Qu’Appelle, but found it heavily guarded and retreated back to Fort Douglas.

Governor Semple arrives and the colony is rebuilt

In November 1815 the newly appointed governor of Red River Colony Robert Semple arrived with around 160 new settlers and Baymen and assisted in re-building the colony.

In Athabasca, John Clark’s brigade arrived late in the season and low on provisions. He sent detachments to the NWC’s English River post (Île-à-la-Crosse), Fort Chipewyan, Slave Lake post and Peace River post. Twenty of Clark’s men perished from the severe climate and hunger. The remaining surrendered to the NWC who maintained them through the winter and gave them transportation out in the spring.[13]

In 1816, the wintering partners at Fort William made plans to destroy the Red River Colony for the second time. The plan was to raise three separate forces which would converge on the colony simultaneously, one would come from Qu’Appelle, the second from Fort William and the third from the Swan River Post as a rear guard. The NWC’s Swan River Post was unmolested by the HBC during this period, because of its distance from the Red River colony and because it was located outside of Selkirk’s land grant. Once together, they would siege the fort and settlement and starve them into submission. The plan was to be set in motion in May. In March, Governor Semple temporarily put Colin Robertson in command of the Red River Colony while he toured the HBC posts in the district.

Fort Gibraltar burned

.png)

In 1816 Robertson, hearing rumours that a party of Métis, Indians and NWC voyageurs were gathering at Fort Gibraltar to attack the colony, captured Fort Gibraltar for the second time on March 17. On searching Duncan Cameron’s room, a copy of a letter was found in which Cameron requested James Grant of Fond du Lac to raise a party of Indians to send to Red River in order to pillage the colony. Upon his return, Governor Semple ordered the fort to be dismantled to prevent it from being used again as a base to strike against the colony. Fort Gibraltar consisted of one house measuring 64 feet long for the partners, one house of 28 feet and one of thirty feet for the men, a kitchen of 15 feet, three warehouses, a blacksmith shop, a stable and an ice house. Its dismantling took 30 men around a week to accomplish, which they did by using axes and hammers to remove the wooden pegs which held the timbers together. The best timbers were floated on rafts to Fort Douglas where they were used to re-enforce the walls and build an additional house. What remained of Gibraltar was then burned to the ground.(p. 40)[3]

Meanwhile, Selkirk set out from Montreal with around 140 discharged soldiers from the De Meuron and De Watteville regiments, his sergeant's detachment of the 37th Regiment and around 150 HBC servants with a number of artillery and even an oven for heating cannonballs. His plan was to travel the Great Lakes route but to avoid Fort William by taking the Fond-du-lac / Rainy Lake route to the Red River. On March 20, Colin Robertson’s men captured Fort Pembina, arrested several NWC employees and Métis and confiscated the fort’s arms and ammunition. Around this time, Governor Semple built the armed schooner named “Cuthullin” to deny NWC access to Lake Winnipeg and put it under the command of Lieutenant Holte. He also erected a battery on the shore of the Red River to prevent NWC boats from passing. In his spare time, Colin Robertson tested the readiness of the HBC blockade by floating an old, empty boat down river, unbeknown to the blockaders. Upon seeing it, the men rushed out and began firing at it without orders.

May 8 found the HBC’s Pierre Pambrun with 25 men transporting 22 bales of furs, 600 bags of pemmican and 23 stands of arms from Brandon House to Fort Douglas. They were driven ashore near the rapids at Portage la Prairie by Cuthbert Grant and around 50 armed Canadians and Métis. Pambrun and his goods were captured and sent to Qu’Appelle. The NWC later testified that they found the furs in some abandoned boats. While a prisoner at Qu’Appelle, Pierre Pambrun observed the Nor’Wester’s preparations for their attack on the Red River Colony. He wrote:

“I remained a prisoner at Qu’Appelle...I saw a blacksmith, by the name of Gardepie...making lances, and daggers; also repairing guns and pistols for the different half-breeds then going upon the expedition for the destruction of the colony...During their stay at Qu’Appelle, their whole amusement was in shooting at the mark, singing war songs, practicing with their lances and telling each other how they would kill the English – meaning the settlers – and they also often told me they were going to kill them like rabbits.”[14]

At the end of May or early June the Qu’Appelle brigade departed consisting of around 80 armed voyageurs with two swivel guns commanded by Alexander MacDonell and an unknown number of Métis following overland on horseback. On the 11th of June, Colin Robertson left the Red River District after a series of disputes with Governor Semple. It is said that Robertson, instead of flying the HBC’s Red Ensign behind his canoe, flew an empty pemmican sack as an insult to the NWC. Around this time the Fort William brigade departed consisting of a number of company employees and partners, Lieutenants Bumby and Missani of the De Meuron’s and former De Meuron soldiers Frederick Heurter and Charles Reinhard all under the joint command of Alexander Mackenzie and Archibald Normal Macleod. For arms they brought two crates of trade guns. En-route they stopped at Fort Lac la Pluie where they were augmented by 20 Indians and another canoe of voyageurs. While there they dispatched an express canoe to Fond du Lac to raise another party of Indians to meet them at the Red River Colony. On June 18 the brigade arrived at Bas de la Rivière where they took on more men as well as muskets and 2 brass three-pound cannon. The firearms were issued out and Reinhard and Heurter were ordered to instruct the voyageurs in the military manual-of-arms and platoon exercise. Some voyageurs refused. One observer stated:

“A Canadian named Forcier positively refused to take a gun, and most of them took them with great reluctance, observing to me, that they were not engaged to take up arms and to make war like soldiers, and wished to do their duty as such – to navigate the canoes and carry goods over carrying places.”[15]

The brigade consisting of around 150 men departed the next day. About the same time the rear-guard left Swan River with forty men under the command of John Macdonald. While leading his brigade to the Red River Colony, Alexander Macdonell dispatched Cuthbert Grant and 25 Métis to plunder the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Brandon House. On June 1, Grant’s men broke open the gates and stole literally everything inside, even the fort’s grind stone. The stolen goods were divided among the raiders except the furs and ammunition which were claimed by the NWC. On June 16 the Qu’Appelle brigade arrived at Portage la Prairie and encamped. Expecting an attack, their stock of provisions and stolen furs were landed and formed into a defensive square on which two swivel guns were mounted. The next day 2 Métis went to Fort Douglas and warned Governor Semple that a large party was at Portage la Prairies and would attack the colony within 2 days. Semple did not believe the NWC had the strength to accomplish it, but began to keep a 24-hour watch at Fort Douglas. Peguis, chief of the local Swampy Indians offered his services to protect the Red River against the Nor’Westers, but Semple declined. Peguis then encamped with his men along the river opposite the colony. On June 18, the HBC’s Patrick Corcoran, who escaped imprisonment at Fort Qu’Appelle arrived at Fort Douglas and informed Semple that a large NWC and Métis force was gathering there to attack the colony. This was Semple’s second warning. Meanwhile, Cuthbert Grant and a party of Canadians departed Portage des Prairie by canoe followed by a number of Métis on horseback, numbering around 50 men total, to deliver 20 bags of much needed pemmican to Bas de la Rivière. Because of the HBC blockades, the party was forced to land 10 miles from the colony at a place called the “Passage” where they loaded the pemmican onto two carts to take them overland past Fort Douglas and re-embark them at Frog Plain. Part of the force remained to rendezvous with the NWC forces from Fort William and Swan River; around 50 continued towards Frog Plain, but not before being ordered to keep as far away from Fort Douglas and the colony as the terrain would allow to avoid a confrontation. This order was given as there was a swamp about three-quarters of a mile opposite Fort Douglas that left only a narrow plain which allowed passage. Before reaching Fort Douglas, around 24 Métis broke off and rode ahead to set up camp at the Frog Plains. The remaining 26 men continued with the carts. The Métis that were included in this party were covered with paint and wore feathers in their hair as the Indians did; not a typical Métis practice. The paint was supposedly given to them by the Canadians in order for them to appear more intimidating to the Red River settlers.

Battle of Seven Oaks

At 6 pm a boy in the watch tower at Fort Douglas saw the party of mounted Métis and gave the alarm. Semple soon arrived, observed them with his spy glass and quickly assembled a party of 20 colonists and Baymen, stating they should go and meet with the Métis and ascertain their intentions. Semple’s men are armed, but Semple gave orders that no one was to shoot unless attacked. However, other witnesses testified that the Baymen bragged they would “have the Métis’ provisions or their lives.” Several Métis entered Lot #3 of the colony to obtain information from the people there. Several colonists then fled towards Fort Douglas for protection. Semple departed Fort Douglas, heading along the road towards the colony and immediately observed the Métis party increase in number. These re-enforcements were either members of the advance party returning from Frog Plain or the party returning from scouting the colony. Seeing the Métis force swell, while at the same time seeing the fleeing colonists, Semple sent John Bourke back to Fort Douglas to bring up a piece of artillery and to dispatch reinforcements to protect the settlers. Semple halted and waited for Bourke and his cannon, but Bourke was delayed and Semple continued towards the Métis. Half a mile from Fort Douglas, Lieutenant Holte’s gun discharged accidentally. Semple was “very much displeased” and scolded him, telling him to be more careful and reiterated that no one should shoot unless fired on. The Canadians and Métis, now numbering around 60 rode towards Semple’s party, seeing this, Semple and his men took several steps backward and began to spread out. When the two parties were within gunshot range of each other, the Métis split into two groups and created a half-circle around Semple’s men giving a “war whoop” while they did so, thus blocking Semple’s route to Fort Douglas and the colony. A Canadian voyageur named Francois Boucher approached Semple. At the same time Bourke departed Fort Douglas with a cannon and 8 or 9 men. Boucher and Semple exchanged some words and Semple reached for the reins of Boucher’s horse, or, according to some accounts, he reached for Boucher’s gun, apparently in an attempt to arrest him. Several shots were immediately fired and Lieutenant Holte and Governor Semple were the first to fall. The Métis dismounted and began firing from behind their horses. The remaining Baymen and settlers rushed towards Semple to give him aid, and being thus concentrated together, were cut down in short order. John Pritchard surrendered and was protected from the Métis by a Canadian who recognized him. The Canadian received several blows from the Métis but kept Pritchard safe. Michael Heden, Michael Kilkenny and Surgeon Mccoy fled towards the river. Mccoy was shot and wounded. Heden and Kilkenny crossed the river in an old boat and returned to Fort Douglas later that night. Meanwhile, Bourke, fearing his cannon would be captured, escorted it back to Fort Douglas and soon returned with a stronger party. As Bourke approached the battle site, he observed the Canadians and Métis still in command of the field. They then called out to Bourke to come fetch the body of Semple, apparently in a mocking tone. Fearing a trick, Bourke again retreated to Fort Douglas. As the party retreated, the Métis fired on it wounding Bourke and killing Duncan McNaughton.[16]

The battle lasted only 25 minutes. In the end, 21 settlers and Baymen were killed, including Governor Semple, while the opposition had but one killed and one wounded. This event would come to be known as the Battle of Seven Oaks after the name of the location at which it took place. There is much debate as to who fired the first shots of the battle. The Nor’Westers and Métis testified that Semple’s men fired first and that the first shot was directed at Boucher who appeared to be resisting Semple’s attempt to arrest him, while the Baymen and settlers testified that the opening shots came from the Canadians and Métis, as the first and second shots felled Lieutenant Holte and Governor Semple. In his report on the incident Commissioner Coltman favoured the Nor’Wester’s story. After the battle, John Pritchard was sent to the Métis camp at Frog Plain and was there under the protection of Cuthbert Grant. The night of the battle, Pritchard negotiated a peace settlement with Cuthbert Grant and on the next day Grant went to Fort Douglas and presented Sheriff Macdonnell, the colony’s second-in-command with Pritchard’s capitulation terms and negotiated a surrender.

Back at Portage des Prairie, Alexander MacDonnell was informed of the Battle of Seven Oaks and departed for Fort Douglas. On June 21, Alexander Mackenzie’s brigade from Fort William encamped at Netley Creek, 40 miles north of the Red River colony and began planning their attack, still unaware of events. The following day Chief Peguis’ Indians retrieved the body of Semple and 9 others and brought them by cart to Fort Douglas and buried them in a mass grave in a grove of trees south-west of the fort. The remaining dead were left on the battlefield. That evening the Red River settlers numbering 180 retreated by boat towards Jack River House. The retreating Red River settlers passed Netley Creek on the 24th and were forced ashore by Alexander Mackenzie’s men. John Pritchard and several others were sent to Fort William as prisoners escorted by Lieutenants Brumby and Misani. The remaining settlers were allowed to continue to Jack River House. Shortly after the rear guard from Swan River arrived. Around the 25th the combined Fort William and Swan River Brigades arrived at Fort Douglas and Alexander Mackenzie took over operations in the district. It is unclear whether the colony was destroyed at this time or whether there was little to destroy in the first place. However, Fort Douglas was left intact, though the colony’s schooner, then anchored in the river near the fort was beached and the sails, cordage and ironwork were removed and the mast was erected as a flag pole in Fort Douglas. The ship’s hull was then burned. Late in June or early July, most NWC partners and voyageurs departed Red River for their wintering posts leaving Fort Douglas in the hands of the around 40 Métis under Cuthbert Grant. Most of the cannons were brought to Athabasca to protect that quarter.

Selkirk takes Fort William

During this time, Lord Selkirk was en route to the Red River Colony with reinforcements. On the 24th of July, while encamped at the Falls of St. Mary (also known as Sault Saint Marie) he was informed by a messenger that the colony had been destroyed. Instead of striking out to re-take his colony, Selkirk immediately plotted a course for the North West Company’s inland headquarters, Fort William, with the intention of rescuing the HBC prisoners and arresting those responsible for the acts of violence against his colony and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Also in July, the British government, in an effort to put an end to the Pemmican War, instructed the Canadian Governor-General Sir John Sherbrooke to send a party into the territory to deliver a proclamation from the Prince Regent calling for an end to the hostilities between the fur companies, the discharging of all soldiers under their employment, the removal of all blockades and the return of all confiscated goods and property. They were also to investigate the incidences and make any necessary arrests. In the fall of 1816, Governor-General Sherbrooke appointed William Coltman and John Fletcher as special commissioners to conduct the investigation, deliver the Prince Regent’s proclamation and to arrest Lord Selkirk. To give them some clout with the Indians, Coltman was commissioned a lieutenant-colonel and Fletcher a major in the British Indian Department.

On August 12, between 10 and 11 am, Selkirk arrived at Fort William. Samuel Wilcocke recorded what happened next:

“His Lordship came into the River Kaministiquiâ with four canoes, attended by a number of soldiers, and by his guard, with whom he encamped about 800 or 900 yards above the Fort, on the opposite shore. Within two or three hours, eleven boats full of men, in the uniform of De Meuron’s Regiment, came into the River, and were followed by one boat and two canoes loaded with arms and stores, &c. The troops immediately joined Lord Selkirk at his encampment, Cannon were landed, and drawn up, pointed at the Fort, and balls were ready piled beside them, as prepared for a siege and bombardment.”[17]

Wilcocke went on to describe the opposing force at Fort William:

"Their numbers together must have exceeded 500 men, and the place, though not properly a Fort, but merely a square of houses and stores, surrounded by a strong and lofty picket fence, contained an ample supply of arms and ammunition, and was capable of considerable resistance."[17]

In his official report, Commissioner Coltman put the number of occupants at Fort William at around 250. At 1 pm on August the 13th, Selkirk informed the proprietor William McGillivray that he was under arrest. McGillivray, accompanied by Kenneth McKenzie and Dr. McLoughlin, went to Selkirk’s tent to give bail. Around this time the Nor’Westers at Fort William began burning their records in the kitchen fireplace to prevent Selkirk from discovering any information about the company’s trading tactics. At 3 pm, two of Selkirk’s officers, McNabb and McPherson and a number of armed soldiers approached the gates of Fort William and asked for permission to enter, presumably to negotiate with the NWC partners. However, as soon as the gates opened, a bugle was blown as a signal and the soldiers rushed through the gates and spread out throughout the fort. The NWC partner Hugh McGillis shouted for his voyageurs to take up arms, but they refused. Selkirk’s men soon had two of the fort’s cannons placed in the centre of the courtyard and guards spread through the fort. It is unknown whether Selkirk had actually planned to capture and occupy Fort William or if this plot was hatched by his subordinates, but Fort William was now firmly in his hands. The next day Lord Selkirk entered the fort, took a tour and received an official protest from the NWC partners. The Nor’Westers planned to retake the fort and hid 83 loaded fusils and a barrel of gunpowder from the fort’s magazine in a hay barn, but a NWC voyageur informed Selkirk of the cache and it was quickly confiscated, preventing any possible takeover. Selkirk’s men also confiscated eight kegs of gunpowder and four cases of trade guns that were ready to be loaded onto canoes with other trade goods heading into the interior. Many of these confiscated guns were issued to Selkirk’s men. The NWC would later sue Selkirk for the theft of these goods.

Around this time another notable incident occurred. On August 10, the men of the NWC’s Athabasca brigade informed Duncan Macleod that Irish Red River settler Owen Keveney was on the Winnipeg River transporting cattle from Fort Albany to the Red River colony and that his men complained of being mistreated.[18] Macleod issued an arrest warrant for Keveney and he was arrested on the 16th. Keveney was escorted to Fort William by Archibald Mclellan, Charles De Rainhard and a party of Métis. En route, they learned that Selkirk was occupying Fort William and they began the journey back to Red River. At a place called the Dalles on the Winnipeg River, according to one source, A Métis named Mainville shot Keveney, and being only wounded, De Reinhard finished him off with his sword. Another source said that De Reinhard wounded Keveney with his sword and Mainville finished him with a gun. Some say Mclellan gave the order to execute Keveney, possibly because he was ill and thus a burden, others say the Métis had been threatening to kill him and that Mainville was simply carrying it through. Regardless, the Nor’Westers made little effort to conceal the crime and De Reinhard, Mainville and Mclellan were eventually arrested and tried for it.[19]

Back at Fort William, Selkirk issued orders to his men on August 15 to prohibit the Nor'Westers from conducting their normal business in order to disrupt the NWC’s trade. As such, no canoes bearing trade goods were allowed to leave for the interior nor were any canoes bearing furs dispatched to Montreal, which disrupted the NWC’s trade for the ensuing year costing the company tens of thousands of pounds. The next day, Selkirk began a detailed inventory of Fort William in order to locate any stolen HBC goods and began searching official and personal correspondences for evidence concerning the destruction of the Red River colony. Among the papers at Fort William was found a list of all the Red River Métis who participated in the destruction of the Red River colony in 1815 as well as 20 bales of goods which were to be sent to these men as gifts. Selkirk also found 30 or 40 packs of furs he claimed were stolen from the HBC’s Brandon House which had apparently been repacked at Fort William. Selkirk sent these papers and the bales of goods and furs to Montreal as evidence. On the 18th, the NWC prisoners were made ready to depart. In all, eight NWC partners were taken prisoner and sent to Montreal, including the head of the company, William McGillivray. Before they departed, each partner’s cassette was searched and personal papers were confiscated. The prisoners were conveyed in three canoes with a fourth following containing armed guards. The canoes were grossly overcrowded, and while on Lake Superior, one canoe overturned and one Kenneth Mackenzie and 8 others drowned. Soon after a NWC canoe arrived at Fort William carrying John McGillivray and Archibald McGillivray who were promptly arrested. On the 25th, two canoes were dispatched under the command of Pierre Pambrun to seize the arms and ammunition at Fort Lac la Pluie, but the officer in charge would not surrender. Even though the fort’s complement was only 7 men, Selkirk’s party was not prepared for a siege so they retreated back to Fort William. Selkirk then dispatched Captain Proteus D’Orsonnens with a second party and 2 field pieces to besiege the fort. The Nor'Westers at Lac la Pluie, now running low on their stores of fish, could not maintain a siege and surrendered.[3] Selkirk also dispatched parties to seize the NWC posts at Fond du Lac and Michipicoton on Lake Superior which was duly accomplished. Capturing Fond du Lac would eventually get Selkirk into some legal trouble as it was on American soil and the goods and furs there were partially owned by John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. Selkirk also hatched a plan to build outposts on the HBC’s land situated between Fort William and Lac la Pluie in order to stop all NWC communication between the two posts. He began cutting a road, but the plans were never completed. In September, Selkirk’s men, while helping the Nor’Westers unload cargo from their sloop, took away its 2 small brass cannons and accompanying ammunition. On September 2, Selkirk gathered together the NWC voyageurs and attempted to induce them to break their contracts and leave the company. One voyageur named Letemps refused to attend and campaigned with several clerks to convince the voyageurs to honour their contracts. For this he was arrested on trumped up charges of theft and was sent to Montreal.

Back at the Red River District, HBC trader Peter Fidler arrived at Lake Manitoba with a cargo of trade goods on September 4. NWC clerk Seraphim Lamarre gathered a small force of Métis to assault Fidler, but finding that Fidler’s party was too large and under the protection of local Indians, Lamarre retreated to Fort Douglas. Alexander Macdonell reinforced Lamarre with 12 or 15 more Métis and Lamarre successfully plundered Fidler’s goods in late September. On September 5, the Nor’Westers at Red River learned of Selkirk’s capture of Fort William, Alexander Macdonell, Archibald Mclellan and Cuthbert Grant met at Bas de la Rivière and proposed to raise a force to retake it, but the Métis refused on account of Selkirk being accompanied by government soldiers, instead the Métis decided to stay and defend the Red River colony. Mclellan then departed for Fort William with a small force of voyageurs and two Métis who agreed to go as far as Lac la Pluie. With Lac la Pluie in his control, Captain D’Orsonnes and a party of 28 Du Meuron soldiers with two cannons went out on snow shoes and sledges to recapture the Red River Colony. In 40 days they reached Pembina and seized it. Hearing rumours that Fort Douglas was only held by a handful of men, D’Orsonnes moved to retake it. He encamped 10 miles south of Fort Douglas in a dense wood and built scaling ladders for a night attack.

On November 7, one William Robinson arrived at Fort William with a warrant issued by a justice of the peace for the western districts and attempted to arrest Lord Selkirk and several of his officers. Selkirk resisted and confined Robinson in the bell house where he stayed for several days and then departed Fort William. Selkirk would eventually be tried for resisting arrest.

In December, the Pemmican War returned to the Athabasca District. The NWC’s Alexander Stewart with 22 men seized the HBC’s Green Lake post and confiscated 11-1/2 packs of furs, 1,500 lbs of dried meat, 3 bags of pemmican and all the post’s trade goods. They then dismantled the post and carried off the doors, hinges, windows & other useful materials. That winter, Archibald Norman McLeod attempted to starve the HBC posts in Athabasca by preventing their Indian hunters from entering any HBC posts and bribing others to switch sides.

Fort Douglas retaken

On January 10, 1817, Captain D’Orsonnes retook Fort Douglas without firing a shot and there captured Mclellan and 15 Nor'Westers. Though not quite abandoned as rumours suggested, dwindling provisions at the fort accounted for the small garrison. Soon after, D’Orsonnes’s men captured 2 sleighs of provisions from Bas de la Rivière en route to relieve the men at Fort Douglas. D’Orsonnes next sent a force to capture Bas de la Rivière in order to secure provisions for Selkirk and his men he expected would arrive in the spring or summer. It was also taken without firing a shot. On February 19, Cuthbert Grant arrived at Rivière la Souris with 26 Métis and attempted to raise a force to go to Fort Douglas and demand the release of NWC prisoners and possibly retake the fort. Grant ordered the NWC voyageurs to take up arms and join him but they refused. He threatened to send them back to Montreal to be punished for disobeying an officer but to no effect. On the 22nd, Grant departed for Fort Douglas with a small party of Métis and freemen. Grant sent a letter to the recently returned ex-governor Miles Macdonell demanding the release of NWC prisoners but was refused. On March 3, Grant devised a plan to set up an ambush at Frog Plain to capture the boats of the Red River settlers that were expected to arrive from Jack River House, however the plan was abandoned. A second plan was to attack Selkirk’s men at Pembina, as the Métis did not wish to return home without a victory, but a dispute between Grant and one of his officers caused the venture to be abandoned while en route.

On March 16, NWC’s Samuel Black seized the HBC’s Île-à-la-Crosse post and Green Lake post for the second time on the 20th. A week later Archibald Norman Macleod invited John Clarke, the officer in charge of the HBC’s Athabasca headquarters Fort Wedderburn, and his clerks to dinner at Fort Chipewyan. While they were away NWC forces seized Fort Wedderburn. Macleod stated that this was revenge for Selkirk’s taking Fort William. Clarke was forced to sign an agreement giving up the posts at Great Slave Lake and Pierre aux Calumets, which were subsequently plundered.

A number of events took place that spring: William McGillivray departed Lachine for Fort William at the head of the yearly brigade of voyageurs. In Montreal, Lady Selkirk personally raised a force of 48 discharged Du Meuron soldiers and 55 Canadian voyageurs intended to reinforce the Red River colony and the HBC in Athabasca. Special Commissioner Coltman, preparing to depart himself for Fort William, questioned the party who stated they were going to Red River as settlers. Since the soldiers had no military firearms and stated that the 2 cases of NWC guns in their possession were for trading, Coltman read them the Regent’s proclamation and allowed them to depart. Commissioners Coltman and Fletcher then left Montreal for Fort William. At Drummond Island, southwest of Sault St. Marie on Lake Huron they picked up a detachment of 40 soldiers from the 70th Regiment commanded by a Lieutenant Austin as a military escort. Passing Lady Selkirk’s re-enforcements, the commissioners arrived at Sault St. Marie in early June. During this time, Selkirk abandoned Fort William and headed for the Red River district. Lac la Pluie was also abandoned and both forts were reoccupied by the NWC.

In Athabasca, the NWC captured and burned the HBC’s remaining posts at Deer Lake and Little Slave Lake.[17] Baymen starved to death as the result of the Nor’Wester’s provisions blockade. The rest were evicted from the district leaving the Nor’Westers in complete control of Athabasca. At Red River, the Baymen at Fort Douglas finally buried the remains of the slain from the Battle of Seven Oaks which had been left on the plain. Also around this time, a party of 10 HBC men were attacked by a party of Indians, which, according to Coltman’s investigation were either Sioux or Assiniboine. Three Baymen were killed and 5 were wounded. It's not clear if these Indians were allied to the NWC or were part of a common raiding party.

Commissioners Coltman and Fletcher

On June 6, 1817 Commissioner William Coltman left Sault St. Marie for Fort William leaving Major Fletcher to catch up with the military contingent. Coltman found Fort William back in possession of the NWC and discovered them making preparations to send a party to Red River to attack Lord Selkirk. Coltman delivered the Regent’s proclamation and the Nor’Westers abandoned their plan. Commissioner Fletcher, still at Sault St. Marie, met McGillivray’s brigade and Lady Selkirk’s reinforcements within days of each other's. McGillivray’s light canoe was allowed to proceed, but Fletcher delayed both brigades and confiscated their arms. Archibald Macdonald of the NWC brigade disregarded Fletcher and continued to the nearby portage. Fletcher and his redcoats detained Macdonald and he and his brigade were not released until June 20 or 22nd. Fletcher and his men then escorted the Nor’Westers to Fort William, the whole brigade amounted to 40 canoes and around 450 men. Fletcher arrived at Fort William on July 1, the remaining canoes arrived between the 2nd and 6th. Instead of following Coltman to Red River, Fletcher decided to remain at Fort William until called for but sent a detachment consisting of a sergeant and thirteen privates of the 70th to Red River on the 9th. On June 20, Selkirk received a copy of the Regent’s proclamation by a NWC officer who received it from Commissioner Coltman. The proclamation had the desired effect and created a temporary cease-fire. Commissioner Coltman finally arrived at Fort Douglas on July 5 and began interviewing the Nor’Westers, Baymen and Métis regarding the events that took place the preceding years and also toured the site of the Battle of Seven Oaks. Coltman paroled most of the prisoners and released others on bail with orders to appear in court in Lower Canada. Amazingly, Coltman made no arrests except for Lord Selkirk who he released on a £6,000 bail. However, a number of wanted men surrendered themselves to Coltman, most notably was Cuthbert Grant who was wanted for murder, theft, and arson.

Coltman's report

Coltman published his report on the Pemmican War a year later in 1818 entitled “A general statement and report relative to the disturbances in the Indian Territories of British North America.”[20] It consisted of more than 500 pages of witness testimonies and other evidence, as well as Coltman’s conclusions and recommendations which were, simply put, that the HBC was the first aggressor, the Red River District was not suitable for any colony, and therefore Selkirk’s plans must have been a tactical move against the Nor’Westers, that the NWC exceeded all lawful and reasonable bounds of self-defence, that both companies should compensate the government for any expenses incurred during this ordeal, and that only the most vigorous of the many crimes should actually go to trial.

Pemmican War trials

In 1818 the Pemmican War trials commenced. Several years previous in 1803, the British government passed “An act for extending the jurisdiction of the courts of justice in the provinces of Lower Canada and Upper Canada” which gave the Canadian courts jurisdiction in the Indian Territories. However, rather than have the Pemmican War trials take place in Quebec or York, the seats of Upper and Lower Canada, Montreal was chosen because many of the fur traders resided there and many of the residents were already familiar with the methods of the fur trade. Selkirk wrote to the Colonial Department in an attempt to have the trials moved to England where he had more influence, and because it was impossible to find an impartial jury in Montreal, it being so intimately connected with the NWC, but the government claimed that they did not have jurisdiction, as the disputes were between commercial bodies. The total charges incurred during the Pemmican War amounted to 38 cases of murder, 60 cases of grand larceny and 13 cases of arson. Only a handful of cases actually went to trial. For example, Colin Robertson and four others were tried for the destruction of Fort Gibraltar, Cuthbert Grant, Francois Boucher and 15 others were tried for the murder of Governor Semple, De Reinhard and McLellan stood trial for the murder of Owen Keveney, and Selkirk himself was tried on charges of theft, false imprisonment and resisting arrest. Since witnesses were expected to pay their own travel expenses and accommodations, Lord Selkirk personally paid the expenses of all HBC witnesses. Several Nor’Westers on trial jumped bail, including Cuthbert Grant. George Campbell, the former Red River colonist who had been arrested for helping steal the Red River colony’s cannons in 1815 escaped prison by obtaining a medical leave and then sneaking out of the hospital at night. However, they were not rigorously perused. Every trial ended in acquittal except one. Charles De Reinhard was convicted of the murder of Owen Keveney. He was sentenced to death by hanging but the sentence was never carried out.

Conflict between the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies did not end with the Prince Regent’s proclamation. In October 1818, Colin Robertson arrived in Athabasca with canoes of trade goods. On the 11th, Nor’Westers at Fort Chipewyan heard rumours that Robertson intended to excite the Indians to massacre them. The Canadian voyageurs refused to work until Robertson was arrested, and therefore Simon McGillivray arrested Robinson who was held in a log privy several months before being sent on to Fort William. Robertson escaped captivity near Cumberland House and returned to Athabasca.

Blockade of the Grand Rapids

On June 16, 1819, William Williams, now Governor of Red River with a party of Baymen and discharged Du Meuron’s armed with muskets and pikes arrived at the northwestern tip of Lake Winnipeg to blockade the Grand Rapids portage. The Grand Rapids is a series of rapids 4 or 5 miles long between Lake Winnipeg and Cedar Lake and was the main causeway to the Athabasca District, which was at this time the most profitable district in Canada. The Baymen built a battery overlooking the rapids consisting of one cannon and two swivel guns, in front of which an abattis of felled trees was made. The second cannon was loaded onto a barge which they anchored in the stream to act as a gun boat. Samuel Wilcocke of the Hudson’s Bay Company wrote:

“In order to strike this blow with security, a number of the discharged soldiers of De Meuron’s regiment, who, in defiance of the proclamation, still retained their engagements with the HBC, and who were chiefly at Red River, were additionally engaged for this especial purpose, being promised, besides their plenty of liquor, tobacco, and provisions, pay at the rate of a dollar a day per man while they continued on this particular service. They were all armed, and equipped; and were principally in their uniforms and with their regimental caps. Williams had two small pieces of brass canon, four pounders, with some swivels, which were brought from Hudson’s Bay, and, accompanied by his military banditti, and a number of the Hudson’s Bay Clerks and servants, all armed.”[21]

The blockade quickly showed results. On the 18th North West Company partners John Campbell and Benjamin Frobisher were captured while crossing the portage, along with their canoemen and two clerks. Campbell was going to Montreal to testify in court in one of the many Pemmican War trials. A NWC brigade of 7 canoes from the English River department was captured on the 20th and two light canoes were captured on the 23rd with another three partners, their servants and crews. NWC partner Angus Shaw told Governor Williams that he was in violation of the Regent’s proclamation to which Williams stated “I do not care a curse for the Prince Regent’s proclamation. Lord Bathurst and Sir John Sherbrook, by whom it was formed are damned rascals.”[22] On June 30, two Hudson’s Bay Company canoes arrived at the blockade. Colin Robertson warned them that a party of Métis and Indians were preparing to assault their position, and on hearing this, the blockade was abandoned and the Baymen retreated to Jack River House.

Governor George Simpson

In August 1820 rumours circulated among the Baymen that the North West Company planned to blockade the Grand Rapids portage which prompted the Hudson’s Bay Company to take appropriate precautions. George Simpson wrote from Jack River House:

"It is currently reported that the N.W. intend to obstruct us at the Grand Rapid, we therefore provided our people with a musket and bayonet each and ten rounds of ball cartridge, and armed ourselves for the purpose of self defense."[23]

It would appear the rumours were true, as that summer Colin Robertson was ambushed by the Nor’Westers at the Grand Rapids and captured a second time, but he again made his escape, this time fleeing into the United States. Tensions remained high in the Red River District. George Simpson wrote that August:

"By accounts received today from Red River, the Nor’Westers are most formidable. I anticipate a very troublesome winter campaign...I shall avoid as much as possible any collision with them but with firmness and determination maintain the rights and interests of the honorable company, and defend their property and our persons by every means within our power."[23]

Merger of the two companies

Hostilities between the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies came to a swift end when the two merged the following year in 1821. The merger was the result of declining profits on both sides and pressure from the British government to settle their differences. In fact, with the merger, many of the combatants of the Pemmican War worked side-by-side, seemingly forgetting their past aggressions.

External links

- Map of the colony

- The Royal Charter of the Hudson's Bay Company

- The Royal Charter of 1670

- The Selkirk Treaty 1817

- John Pritchard biography

References

- 1 2 3 "The Selkirk Treaty". The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Chapter 1 pages 5-7). Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ↑ Joseph James Hargrave (1871). Red River. author. p. 488. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Samuel Hull Wilcocke; Simon McGillivray; Edward Ellice (1817). A Narrative of Occurrences in the Indian Countries of North America, Since the Connexion of the Right Hon. the Earl of Selkirk with the Hudson's Bay Company, and His Attempt to Establish a Colony on the Red River;: With a Detailed Account of His Lordship's Military Expedition To, and Subsequent Proceedings at Fort William, in Upper Canada.. B. McMillan, Bow-Street, Covent-Garden, printer to His Royal Highness the Prince Regent. Sold by T. Egerton, Whitehall; Nornaville and Fell, New Bond-Street; and J. Richardson, Royal Exchange. p. 52. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ↑ Wilcocke, Samuel (1817). A narrative of occurrences in the Indian countries of North America. London. pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Fargo: North Dakota. 1913. p. 467.

- ↑ Simpson, George, Peace River: a canoe voyage from Hudson's Bay to Pacific, by Sir George Simpson in 1828; journal of the late chief factor, Archibald Mcdonald (Hon. Hudson's Bay Company) who accompanied him...(Rutland, Vermont: 1971), 7.

- ↑ "The Royal Charter of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC corporate collections)". 2014-08-18.

- ↑ Hawkett, John, Statement respecting the Earl of Selkirk's settlement ... (London: 1817), 46.

- ↑ Hudson’s Bay Company charter, 1670.

- ↑ Bryce, George, A Remarkable History of the Hudson’s Bay Company...(London: 1900), 262.

- ↑ Report of Trials in the Courts of Canada Relative to the Destruction of the Earl of Selkirk’s Settlement on the Red River (London: 1820), 16.

- ↑ Selkirk, Douglas (5th earl of Selkirk), A Letter to the Earl of Liverpool from the Earl of Selkirk... 196.

- ↑ Jennifer S. H. Brown (1985). "John Clarke (Dictionary of Canadian Biography)". University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- ↑ Narratives of John Pritchard, Pierre C. Pambrun, and Frederick Damien Huerter...(London: 1819), 48

- ↑ Narratives of John Pritchard, Pierre C. Pambrun, and Frederick Damien Huerter...(London: 1819), 60.

- ↑ Narratives of John Pritchard, Pierre C. Pambrun, and Frederick Damien Huerter...(London: 1819), 30.

- 1 2 3 Wilcocke, 67

- ↑ "Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Owen Keveny)". Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ↑ "Peel's Prairie Provinces (Report at large of the trial of Charles de Reinhard)". Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- ↑ Public Archives of Canada, MG 19, E2.

- ↑ Wilcocke, 5-6.

- ↑ Blue, John, Alberta, Past and Present, Historical and Biographical (Chicago: 1924), Vol. 1, 58.

- 1 2 Simpson, George, Journal of Occurrences in the Athabasca Department by George Simpson, 1820-1821 (Toronto: The Champlain society: 1938), 16.