Pemphigus

| Pemphigus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | dermatology |

| ICD-10 | L10 |

| ICD-9-CM | 694.4 |

| OMIM |

169600 Benign Chronic ~ 169610 ~ Vulgaris, Familial |

| DiseasesDB | 33489 |

| MedlinePlus | 000882 |

| eMedicine |

derm/317 derm/318 ~ foliaceus derm/314 Drug-induced ~ derm/543 ~ herpetiformis derm/315 ~ IgA derm/319 ~ Vulgaris derm/535 ~Paraneoplastic derm/150 Benign ~ (Hailey-Hailey Disease) |

| Patient UK | Pemphigus |

| MeSH | D010392 |

Pemphigus (/ˈpɛmfɪɡəs/ or /pɛmˈfaɪɡəs/) is a rare group of blistering autoimmune diseases that affect the skin and mucous membranes.[1]

In pemphigus, autoantibodies form against desmoglein. Desmoglein forms the "glue" that attaches adjacent epidermal cells via attachment points called desmosomes. When autoantibodies attack desmogleins, the cells become separated from each other and the epidermis becomes "unglued", a phenomenon called acantholysis. This causes blisters that slough off and turn into sores. In some cases, these blisters can cover a significant area of the skin.[2]

Originally, the cause of this disease was unknown, and "pemphigus" was used to refer to any blistering disease of the skin and mucosa. In 1964, researchers found that the blood of patients with pemphigus contained antibodies to the layers of skin that separate to form the blisters.[3][4] In 1971, an article investigating the autoimmune nature of this disease was published.[5][6]

Types

There are several types of pemphigus which vary in severity: pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, Intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis, and paraneoplastic pemphigus.

- Pemphigus vulgaris (PV - ICD-10 L10.0) is the most common form of the disorder and occurs when antibodies attack Desmoglein 3. Sores often originate in the mouth, making eating difficult and uncomfortable. Although pemphigus vulgaris may occur at any age, it is most common among people between the ages of 40 and 60. It is more frequent among Ashkenazi Jews. Rarely, it is associated with myasthenia gravis. Nail disease may be the only finding and has prognostic value in management. [7]

- Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is the least severe of the three varieties. Desmoglein 1, the protein that is destroyed by the autoantibody, is found in only the top dry layer of the skin. PF is characterized by crusty sores that often begin on the scalp, and may move to the chest, back, and face. Mouth sores do not occur. This form is also frequent among Ashkenazi Jews. It is not as painful as pemphigus vulgaris, and is often mis-diagnosed as dermatitis or eczema [8]

- Intraepidermal neutrophilic IgA dermatosis is characterized histologically by intraepidermal bullae with neutrophils, some eosinophils, and acantholysis.[9]

- The least common and most severe type of pemphigus is paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). This disorder is a complication of cancer, usually lymphoma and Castleman's disease. It may precede the diagnosis of the tumor. Painful sores appear on the mouth, lips, and the esophagus. In this variety of pemphigus, the disease process often involves the lungs, causing bronchiolitis obliterans (constrictive bronchiolitis). Though much less frequent, it is still found the most in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Complete removal of and/or cure of the tumor may improve the skin disease, but lung damage is generally irreversible.

- Endemic pemphigus foliaceus, including the Fogo Selvagem, the new variant of endemic pemphigus folaiceus in El Bagre, Colombia, South America, and the Tunisian endemic pemphigus in North Africa.[10]

Note that Hailey-Hailey disease, also called familial benign pemphigus, is an inherited (genetic) skin disease, not an autoimmune disease. It is therefore not considered part of the Pemphigus group of diseases.[11]

Diagnosis

Pemphigus defines a group of autoimmune interepithelial blistering diseases that are characterized by loss of normal cell-cell adhesion (acantholysis), and by the presence of pathogenic (predominantly IgG) autoantibodies reacting against epithelial adhesion molecules.[12] Pemphigus is further divided in two major subtypes: pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF). However, several other disorders such as IgA pemphigus, IgE pemphigus, pemphigus herpetiformis, drug induced pemphigus, Senear Usher syndrome and endemic pemphigus foliaceus exist;recognized by a dermatologist from the appearance and distribution of the skin lesions. It is also commonly diagnosed by specialists practicing otolaryngology- head and neck surgery, periodontists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons and eye doctors, as lesions can affect the eyes and mucous membrane of the oral cavity. Intraorally it resembles the more common diseases lichen planus and mucous membrane pemphigoid.[13] Definitive diagnosis requires examination of a skin or mucous membrane biopsy by a dermatopathologist or oral pathologist. The skin biopsy is taken from the edge of a blister, prepared for histopathology and examined with a microscope. The pathologist looks for an intraepidermal vesicle caused by the breaking apart of epidermal cells (acantholysis). Thus, the superficial (upper) portion of the epidermis sloughs off, leaving the bottom layer of cells on the "floor" of the blister. This bottom layer of cells is said to have a "tombstone appearance".

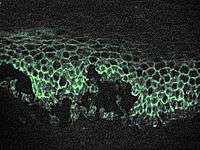

Definitive diagnosis also requires the demonstration of anti-desmoglein autoantibodies by direct immunofluorescence on the skin biopsy. These antibodies appear as IgG deposits along the desmosomes between epidermal cells, a pattern reminiscent of chicken wire. Anti-desmoglein antibodies can also be detected in a blood sample using the ELISA technique.

Half of people with pemphigus have mouth lesions alone during the first year but develop skin lesions later.

Classification

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune blistering diseases that may be classified into the following types:[14]

- Pemphigus vulgaris, of which there several forms:

- Pemphigus foliaceus, of which there several forms:

- Pemphigus erythematosus or Senear-Usher Syndrome

- Endemic pemphigus foliaceus with its three variants, Fogo Selvagem, the new variant endemic pemphigus Foliaeus and Tunisian endemic pemphigus foliaceus

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus

- IgA pemphigus, of which there several forms:

Treatment

If not treated, pemphigus can be fatal from an overwhelming infection of the sores. The most common treatment is the administration of oral steroids, especially prednisone, often in high doses. The side effects of corticosteroids may require the use of so-called steroid-sparing or adjuvant drugs. The immunosuppressant CellCept (mycophenolic acid) is among those being used.[15]

Intravenous gamma globulin (IVIG) may be useful in severe cases, especially paraneoplastic pemphigus. Mild cases sometimes respond to the application of topical steroids. Recently, Rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, was found to improve otherwise untreatable severe cases of Pemphigus vulgaris.[16][17]

All of these drugs may cause severe side effects, so the patient should be closely monitored by doctors. Once the outbreaks are under control, dosage is often reduced, to lessen side effects.

One of the most dangerous side effects of high dosage steroid treatments is intestinal perforations, which may lead to sepsis. Steroids and other medications being taken to treat Pemphigus may also mask the effects of the perforations. Patients on high dosages of oral steroids should closely monitor their GI health.

If paraneoplastic pemphigus is diagnosed with pulmonary disease, a powerful cocktail of immune suppressant drugs is sometimes used in an attempt to halt the rapid progression of bronchiolitis obliterans, including methylprednisolone, ciclosporin, azathioprine, and thalidomide. Plasmapheresis may also be useful.

If skin lesions do become infected, antibiotics may be prescribed. Tetracycline antibiotics have a mildly beneficial effect on the disease and are sometimes enough for Pemphigus Foliaceus. In addition, talcum powder is helpful to prevent oozing sores from adhering to bedsheets and clothes.

Pain is a common part of the disease. Only one literature review on peer-reviewed articles reporting pemphigous pain management has been published in the professional medical literature.[18]

Other animals

Pemphigus foliaceus has been recognized in pet dogs, cats, and horses and is the most common autoimmune skin disease diagnosed in veterinary medicine. Pemphigus foliaceus in animals produces clusters of small vesicles that quickly evolve into pustules. Pustules may rupture, forming erosions or become crusted. Left untreated, pemphigus foliaceus in animals is life-threatening, leading to not only loss of condition but also secondary infection.

Pemphigus vulgaris is a very rare disorder described in pet dogs and cats. Paraneoplastic pemphigus has been identified in pet dogs.

See also

- Pemphigus herpetiformis

- Hailey-Hailey disease (familial benign pemphigus)

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Pemphigoid

- List of conditions caused by problems with junctional proteins

- List of immunofluorescence findings for autoimmune bullous conditions

Footnotes

- ↑ Yeh SW, Ahmed B, Sami N, Ahmed AR (2003). "Blistering disorders: diagnosis and treatment". Dermatologic Therapy. 16 (3): 214–23. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8019.2003.01631.x. PMID 14510878.

- ↑ International Pemphigus & Pemphigoid Foundation: What is Pemphigus?

- ↑ Beutner, EH; Jordon, RE (November 1964). "Demonstration of skin antibodies in sera of pemphigus vulgaris patients by indirect immunofluorescent staining". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 117: 505–510. doi:10.3181/00379727-117-29622. PMID 14233481.

- ↑ "Dermatology Foundation: BEUTNER, JORDAN SHARE 2000 DERMATOLOGY FOUNDATION DISCOVERY AWARD".

- ↑ Jordon, Robert E.; Sams, Jr., W. Mitchell; Diaz, Gustavo; Beutner, Ernst H. (1971). "NEGATIVE COMPLEMENT IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE IN PEMPHIGUS". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 57 (6): 407–410. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12293273. PMID 4108416.

- ↑ Serratos, BD; Rashid, RM (Jul 15, 2009). "Nail disease in pemphigus vulgaris.". Dermatology online journal. 15 (7): 2. PMID 19903430.

- ↑ Abreu-Velez AM, Calle-Isaza J, Howard MS. Autoimmune epidermal blistering diseases. Our Dermatol Online. 2013;4(Suppl.3):631-646

- ↑ Abreu Velez AM, Calle-Isaza J, Howard MS. Autoimmune epidermal blistering diseases. Our Dermatol Online. 2013;4(Suppl.3):631-646. DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20134.158

- ↑ Abreu Velez AM, Calle-Isaza J, Howard MS. Autoimmune epidermal blistering diseases. Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(Suppl.3): 631-646. DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20134.158

- ↑ 1. Abréu Vélez AM, Hashimoto T, Tobón S, Londoño ML, Montoya F, Bollag, WB, Beutner, E., is a unique form of endemic pemphigus in Northern Colombia. J Am Acad Dermatol. Oct(49),4:609-614,2003

- ↑ Hailey Hailey Disease Society

- ↑ 16. Abreu Velez AM, Calle-Isaza J, Howard MS. Autoimmune epidermal blistering diseases. Our Dermatol Online. 2013; 4(Suppl.3): 631-646. DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20134.158

- ↑ Sapp, J. Philip; Eversole, Lewis R.; Wysocki, George P. (1997). Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-8016-6918-7.also here

- ↑ Stanley, John R. (2003). "Chapter 59: Pemphigus". In Freedberg; et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 559. ISBN 0-07-138067-1.

- ↑ British Association of Dermtologists, Steroid sparing (or adjuvant) drugs

- ↑ Ahmed AR, Spigelman Z, Cavacini LA, Posner MR (2006). "Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with rituximab and intravenous immune globulin". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (17): 1772–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa062930. PMID 17065638.

- ↑ Joly P, Mouquet H, Roujeau JC, et al. (2007). "A single cycle of rituximab for the treatment of severe pemphigus". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (6): 545–52. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067752. PMID 17687130.

- ↑ Rashid, RM; Candido, KD (Oct 2008). "Pemphigus pain: a review on management.". The Clinical journal of pain. 24 (8): 734–5. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31817af6fc. PMID 18806540.

External links

- International Pemphigus & Pemphigoid Foundation

- Pemphigus vulgaris, article from eMedicine.

- Pemphigus foliaceus, article from eMedicine.

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus, article from eMedicine.

- Paraneoplastic Pemphigus Survivor

- Pemphigus Vulgaris

- Australasian Blistering Diseases Foundation

- Detection_of_Mercury_and_Other_Undetermined_Materials_in_Skin_Biopsies_of_Endemic_Pemphigus_Foliaceus

- Endemic pemphigus foliaceus over a century: Part I

- Analyses of autoantigens in a new form of endemic pemphigus foliaceus in Colombia

- DermAtlas 65817101

- Questions and Answers about Pemphigus - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases