Petar Zrinski

| Petar Zrinski Petar IV. Zrinski Zrínyi Péter | |

|---|---|

| Ban of Croatia | |

| |

| Ban of Croatia | |

| Reign | 24 January 1665 – 29 March 1670 |

| Predecessor | Miklós Zrínyi |

| Successor | Nikola Erdödy |

| Spouse(s) | Katarina Zrinska |

|

Issue | |

| Father | Juraj V Zrinski, Ban of Croatia |

| Mother | Magdalena Zrinski (born Széchy) |

| Born |

6 June 1621 Vrbovec, Croatia |

| Died |

30 April 1671 (aged 49) Wiener Neustadt, Austria |

| Buried | Zagreb Cathedral, Croatia |

Petar Zrinski (Hungarian: Zrínyi Péter) (6 June 1621 – 30 April 1671) was a Croatian Ban (Viceroy) and writer. A member of the Zrinski noble family, he was noted for his role in the attempted Croatian-Hungarian rebellion of 1664-1670 which ultimately led to his execution for high treason.

Zrinski family

Petar Zrinski was born in Vrbovec, a small town near Zagreb, the son of Juraj V Zrinski and Magdalena Szechy. His father and great-grandfather (Nikola Šubić Zrinski) had been viceroys or Ban of Croatia, which was then a nominal Kingdom in personal union with the Hungarian Kingdom. His brother was the Croatian-Hungarian general and poet Miklós Zrínyi.

His family had possessed large estates throughout all of Croatia and had family ties with the second largest Croatian landowners, the Frankopan family. He married Anna Katarina, the half-sister of Fran Krsto Frankopan, and they lived in large castles of Ozalj (in Central Croatia) and Čakovec in Medjimurje, northernmost county of Croatia. Through his daughter, Ilona Zrínyi, he was the grandfather of famed Hungarian general Francis II Rákóczi.

Zrinski-Frankopan plot

During the Austro–Turkish War (1663–1664) Petar Zrinski fought the Turks at the siege of Novi Zrin Castle along with his brother Nikola. After the unpopular Peace of Vasvár (1664) between Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I and the Ottoman Empire, he joined Croatian and Hungarian nobility who were disappointed by the failure to remove the Ottomans completely from Hungarian territory and embarked on a conspiracy to remove foreign influence, including Habsburg rule, from the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen.

Petar Zrinski was involved in the poorly organized rebellion together with his older brother Nikola Zrinski and his brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan and Hungarian noblemen. In the preparations of the plot, plans were disrupted by the death of Nikola Zrinski in the woods near Čakovec by a wounded wild boar — later rumours claimed he was murdered by Habsburg agents, however, this claim could never be substantiated. Petar succeeded his brother as Ban of Croatia.

The conspirators, who hoped to gain foreign aid in their attempts, entered into secret negotiations with a number of nations — including France, Sweden, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Republic of Venice, even the Ottomans; nevertheless, no state wanted to intervene – in fact, the High Porte informed Leopold of the conspiracy in 1666.[1] The Austrians also had informants inside the group of nobles. However, no action was taken, because the conspirators had made little traction and were bound by inaction.

Final revolt and suppression

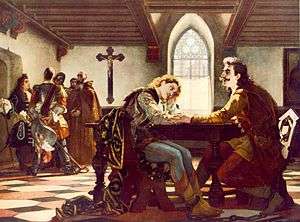

Zrinski and Frankopan, unaware of their detection, nevertheless continued planning the plot. When they tried to trigger a revolt by taking command of the Croatian troops, they were quickly repulsed, and the revolt collapsed. Finding themselves in a desperate position, they finally went to Vienna to ask emperor Leopold I of the Habsburg dynasty for pardon. They were offered safe conduct but were arrested. A tribunal chaired by chancellor Johann Paul Hocher sentenced them to death for high treason on 23 and 25 April 1671.[2]

For Petar Zrinski the verdict was read as follows:

- ...he committed the greater sin than the others in aspiring to obtain the same station as his Majesty, that is, to be an independent Croatian ruler, and therefore he indeed deserves to be crowned not with a crown, but with a bloody sword. [3]

Zrinski and Frankopan were executed by beheading on 30 April 1671 in Wiener Neustadt. Their estates were confiscated and their families relocated — Zrinski's wife, Katarina Zrinska, was interned in the Dominican convent in Graz where she fell mentally ill and remained until her death in 1673, two of his daughters died in a monastery, and his son Ivan Antun (John Anthony) died in madness, after twenty years of terrible imprisonment and torture, on 11 November 1703. The oldest daughter Jelena, already married in northeastern Upper Hungary, survived and continued the resistance.

Some 2,000 other nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown. Two more leading conspirators — Ferenc Nádasdy, Chief Justice of Hungary, and Styrian governor, Count Hans Erasmus von Tattenbach — were executed (the latter in Graz on 1 December 1671).[4]

In the view of Emperor Leopold, the Croats and Hungarians had forfeited their right to self-administration through their role in the attempted rebellion. Leopold suspended the constitution - already, the Zrinski trial had been conducted by an Austrian, not a Hungarian court - and ruled Hungary like a conquered province.[5]

Poetry

Beside being one of the most important military figures of 17th century Croatia, Zrinski is also known for his literary works. Along with his wife Katarina, brother Nikola VII Zrinski and brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan he contributed greatly to 17th century Croatian poetry.

Legacy

The bones of Zrinski and Frankopan were found in Austria in 1907 and brought to Zagreb in 1919, where they were reburied in the Zagreb Cathedral.[6]

Zrinski and Frankopan are still widely regarded as national heroes in Croatia as well as Hungary. Their portraits are depicted on the obverse of the Croatian 5 kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2001.[7]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Petar Zrinski. |

References

- ↑ Other sources attribute this information to a translator at the Ottoman Court who was paid by Austrian intelligence.

- ↑ Paul Lendvai, Ann Major: The Hungarians: a thousand years of victory in defeat. Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-11969-4, 2003 (p.143)

- ↑ "... die größten Sünden begangen habe, in seinen Bestrebungen sich zu einem unabhängigen Kroatischen Herrscher krönen lassen zu wollen. Statt einer Krone erwarte ihn ein blutiges Schwert."

- ↑ Stephan Vajda, Felix Austria. Vienna, 1988, p. 302

- ↑ Stephan Vajda, Felix Austria. Vienna, 1988, p. 136

- ↑ Stadtmuseum Wiener Neustadt

- ↑ Croatian National Bank. Features of Kuna Banknotes: 5 kuna (1993 issue) & 5 kuna (2001 issue). – Retrieved on 30 March 2009.

| Preceded by Nikola Zrinski |

Ban of Croatia 1665–1670 |

Succeeded by Nikola Erdödy |