Shlisselburg

| Shlisselburg (English) Шлиссельбург (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| - Town[1] - | |

A street in Shlisselburg | |

.svg.png) Location of Leningrad Oblast in Russia | |

Shlisselburg | |

|

| |

.png) |

|

|

| |

| Administrative status (as of June 2013) | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Leningrad Oblast[1] |

| Administrative district | Kirovsky District[1] |

| Settlement municipal formation | Shlisselburgskoye Settlement Municipal Formation[1] |

| Administrative center of | Shlisselburgskoye Settlement Municipal Formation[1] |

| Municipal status (as of May 2010) | |

| Municipal district | Kirovsky Municipal District[2] |

| Urban settlement | Shlisselburgskoye Urban Settlement[2] |

| Administrative center of | Shlisselburgskoye Urban Settlement[2] |

| Statistics | |

| Population (2010 Census) | 13,170 inhabitants[3] |

| Time zone | MSK (UTC+03:00)[4] |

| Founded | 1702 |

| Town status since | 1780[5] |

| Previous names | Petrokrepost (until 1992)[5] |

| Postal code(s)[6] | 187320 |

|

| |

| Shlisselburg on Wikimedia Commons | |

Shlisselburg (Russian: Шлиссельбург; IPA: [ʂlʲɪsʲɪlʲˈburk]; German: Schlüsselburg; Swedish: Nöteborg) is a town in Kirovsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located at the head of the Neva River on Lake Ladoga, 35 kilometers (22 mi) east of St. Petersburg. From 1944 to 1992, it was known as Petrokrepost (Петрокрепость). Population: 13,170 (2010 Census);[3] 12,401 (2002 Census);[7] 12,589 (1989 Census).[8]

The fortress and the town center are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

History

Fortress

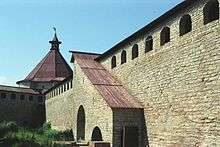

A wooden fortress named Oreshek (Орешек) or Orekhov (Орехов) was built by Grand Prince Yury of Moscow (in his capacity as Prince of Novgorod) on behalf of the Novgorod Republic in 1323. It guarded the northern approaches to Novgorod and access to the Baltic Sea. The fortress is situated on Orekhovets Island whose name refers to nuts in Swedish as well as in Finnish (Pähkinäsaari, "Nut Island") and Russian languages.

After a series of conflicts, a peace treaty was signed at Oreshek on August 12, 1323 between Sweden and Grand Prince Yury and the Novgorod Republic. This was the first agreement on the border between Eastern and Western Christianity running through present-day Finland. A modern stone monument to the north of the Church of St. John in the fortress commemorates the treaty.

Twenty-five years later, King Magnus Eriksson attacked and briefly took the fortress during his crusade in the region in 1348–1352.[9] It was largely ruined by the time the Novgorodians retook the fortress in 1351. The fortress was rebuilt in stone in 1352 by Archbishop Vasily Kalika of Novgorod (1330–1352), who, according to the Novgorod First Chronicle, was sent by the Novgorodians after several Russian and Lithuanian princes ignored the city's pleas to help them rebuild and defend the fort.[10][11] The remnants of the walls of 1352 were excavated in 1969 and can be seen just north of the Church of St. John in the center of the present fortress.

The fort was captured by Sweden in 1611 during the Ingrian War. As part of the Swedish Empire, the fortress was known as Nöteborg ("Nut-fortress") in Swedish or Pähkinälinna in Finnish, and became the center of the north-Ingrian Nöteborg county (slottslän).

In 1702, during the Great Northern War, the fortress was taken by Russians under Peter the Great in an amphibious assault: 250 Swedish soldiers defended the fort for ten days before surrendering. Russian losses were 6,000 men against 110 Swedish losses. It was then given its current name, Shlisselburg, a corruption of Schlüsselburg. The name, meaning "Key-fortress" in German, refers to Peter's perception of the fortress as the "key to Ingria".

During Imperial times, the fortress was used as a notorious political prison; among its famous prisoners were Wilhelm Küchelbecker, Mikhail Bakunin and, for thirty-eight years, Walerian Łukasiński. Ivan VI was murdered in the fortress in 1764, and Lenin's brother, Aleksandr Ulyanov, was hanged there as well.

Out of original ten towers, the fortress retains only six (five Russian and one Swedish). The remains of a church inside the fortress were transformed into a memorial to the fortress's defenders. The fortress has been the site of an annual rock concert since 2003. There is also a museum of political prisoners of the Russian Empire and a small collection of World War II artillery.

Town

The town on the mainland opposite the island fortress was founded in 1702 by Peter the Great. In the course of Peter's administrative reform, Shlisselburg was included into Ingermanland Governorate (known since 1710 as St. Petersburg Governorate). In 1727, it became a part of Sankt-Petersburgsky Uyezd, and in 1755 Shlisselburgsky Uyezd was established. In 1914, Sankt-Peterburgsky Uyezd was renamed Petrogradsky Uyezd.[12] On February 14, 1923, Shlisselburgsky Uyezd was merged into Petrogradsky Uyezd.[13] In January 1924, the uyezd was renamed Leningradsky.[13] St. Petersburg Governorate was twice renamed, first Petrograd Governorate and subsequently Leningrad Governorate.

On August 1, 1927, the uyezds were abolished.[13] Shlisselburg was made a town of okrug significance and belonged to Leningrad Okrug.{[14] On August 19, 1930, Leningradsky Prigorodny District, with the administrative center in Leningrad, was established.[14] On August 19, 1936, the district was abolished and Shlisselburg became the town of oblast significance.[14]

During World War II, the town (but not the fortress) was seized by German troops. German occupation lasted from September 8, 1941 to January 18, 1943. The recapture of Shlisselburg in January 1943 by the Red Army reopened access to besieged Leningrad. In 1944, the town's name was changed to Petrokrepost (lit., Peter's fortress).[5] Shlisselburg regained its former name in 1992.[5]

In 2010, the administrative structure of Leningrad Oblast was harmonized with its municipal structure,[15] and Shlisselburg became a town of district significance, subordinated to Kirovsky District.

Administrative and municipal status

Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated within Kirovsky District as Shlisselburgskoye Settlement Municipal Formation.[1] As a municipal division, Shlisselburgskoye Settlement Municipal Formation is incorporated within Kirovsky Municipal District as Shlisselburgskoye Urban Settlement.[2]

Economy

Industry

There are several shipyards in Shlisselburg.[16]

The main company operating in the city is "Nevsky shipyard" which was founded in 1913 when the ship repair workshops were established.[17] The main activities of the company are: shipbuilding, ship repair, modernization and renovation and machine-building[18]

Transportation

The railway platform of Petrokrepost, which has passenger service to Ladozhsky railway station in St. Petersburg, is located on the other bank of the Neva opposite of Shlisselburg.

The A120 road, which encircles St. Petersburg, and the M18 Highway, which connects St. Petersburg and Murmansk, pass several kilometers south of the town.

The Neva and Lake Ladoga are navigable. In the beginning of the 19th century, a system of canals bypassing Lake Ladoga was built, which at the time was a part of Mariinsky Water System, connecting the Neva with the Volga River. In particular, the New Ladoga Canal connects the Volkhov and the Neva Rivers. It replaced the Old Ladoga Canal built by Peter the Great, which thus became disused and decayed. The canals collectively are known as the Ladoga Canal. The canals originate from the Neva in Shlisselburg.

Architecture

The town does not retain many historical buildings, apart from a handful of 18th-century churches. Perhaps the most remarkable landmark is the Old Ladoga Canal, started at the behest of Peter the Great in 1719 and completed under the guidance of Fieldmarshal Munnich twelve years later. The canal stretches for 104 versts (111 km); its granite sluices date from 1836.

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oblast Law #32-oz

- 1 2 3 4 Law #100-oz

- 1 2 Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года (2010 All-Russia Population Census) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ↑ Правительство Российской Федерации. Федеральный закон №107-ФЗ от 3 июня 2011 г. «Об исчислении времени», в ред. Федерального закона №271-ФЗ от 03 июля 2016 г. «О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон "Об исчислении времени"». Вступил в силу по истечении шестидесяти дней после дня официального опубликования (6 августа 2011 г.). Опубликован: "Российская газета", №120, 6 июня 2011 г. (Government of the Russian Federation. Federal Law #107-FZ of June 31, 2011 On Calculating Time, as amended by the Federal Law #271-FZ of July 03, 2016 On Amending Federal Law "On Calculating Time". Effective as of after sixty days following the day of the official publication.).

- 1 2 3 4 Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 525. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- ↑ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (Russian)

- ↑ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian). Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Demoscope Weekly (1989). "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ↑ Michael C. Paul, "Archbishop Vasilii Kalika, the Fortress at Orekhov and the Defense of Orthodoxy," in Alan V. Murray, ed., The Clash of Cultures on the Medieval Baltic Frontier (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2009): 266–267.

- ↑ Arseny Nikolayevich Nasonov, ed. "Новгородская первая летопись: старшего и младшего изводов". Moscow and Leningrad, 1950, p. 100

- ↑ Michael C. Paul. "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 8, No. 2, pp. 237, 249; Paul, "Archbishop Vasilii Kalika," 257-258.

- ↑ Старые карты Петербургского (Санкт-Петербургского) уезда (in Russian). Картографическая энциклопедия. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Петроградский уезд (1917 г. - январь 1924 г.), Ленинградский уезд (январь 1924 г.- август 1927 г.) (in Russian). Система классификаторов исполнительных органов государственной власти Санкт-Петербурга. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Ленинградский Пригородный район (август 1930 г. - август 1936 г.) (in Russian). Система классификаторов исполнительных органов государственной власти Санкт-Петербурга. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Отчет о работе комитета по взаимодействию с органами местного самоуправления Ленинградской области в 2010 году (in Russian). Комитет по печати и связям с общественностью Ленинградской области. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ↑ Промышленные предприятия города Шлиссельбурга (in Russian). www.shlisselburg.ru. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.nssz.ru/en/istoriya-verfi.html

- ↑ http://www.nssz.ru/en/uslugi.html

Sources

- Законодательное собрание Ленинградской области. Областной закон №32-оз от 15 июня 2010 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Ленинградской области и порядке его изменения», в ред. Областного закона №23-оз от 8 мая 2014 г. «Об объединении муниципальных образований "Приморское городское поселение" Выборгского района Ленинградской области и "Глебычевское сельское поселение" Выборгского района Ленинградской области и о внесении изменений в отдельные Областные законы». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Вести", №112, 23 июня 2010 г. (Legislative Assembly of Leningrad Oblast. Oblast Law #32-oz of June 15, 2010 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Leningrad Oblast and on the Procedures for Its Change, as amended by the Oblast Law #23-oz of May 8, 2014 On Merging the Municipal Formations of "Primorskoye Urban Settlement" in Vyborgsky District of Leningrad Oblast and "Glebychevskoye Rural Settlement" in Vyborgsky District of Leningrad Oblast and on Amending Various Oblast Laws. Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Законодательное собрание Ленинградской области. Областной закон №100-оз от 29 ноября 2004 г. «Об установлении границ и наделении соответствующим статусом муниципального образования Кировский муниципальный район и муниципальных образований в его составе», в ред. Областного закона №17-оз от 6 мая 2010 г «О внесении изменений в некоторые областные законы в связи с принятием федерального закона "О внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Российской Федерации в связи с совершенствованием организации местного самоуправления"». Вступил в силу через 10 дней со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Вестник Правительства Ленинградской области", №40, 20 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Leningrad Oblast. Oblast Law #100-oz of November 29, 2004 On Establishing the Borders of and Granting an Appropriate Status to the Municipal Formation of Kirovsky Municipal District and to the Municipal Formations It Comprises, as amended by the Oblast Law #17-oz of May 6, 2010 On Amending Certain Oblast Laws Due to the Adoption of the Federal Law "On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Due to the Improvement of the Organization of the Local Self-Government". Effective as of after 10 days from the day of the official publication.).

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Schlüsselburg. |

- Official website of Shlisselburg (Russian)

- Unofficial website of Shlisselburg (Russian)

- Official website of the fortress museum

- Official website of the fortress museum (Russian)

- Article and pictures of Shlisselburg fortress