Planetary habitability

Planetary habitability is the measure of a planet's or a natural satellite's potential to have habitable environments hospitable to life.[1] Habitable environments do not need to contain life. Life may develop directly on a planet or satellite or be transferred to it from another body, a hypothetical process known as panspermia. As the existence of life beyond Earth is unknown, planetary habitability is largely an extrapolation of conditions on Earth and the characteristics of the Sun and Solar System which appear favorable to life's flourishing—in particular those factors that have sustained complex, multicellular organisms and not just simpler, unicellular creatures. Research and theory in this regard is a component of planetary science and the emerging discipline of astrobiology.

An absolute requirement for life is an energy source, and the notion of planetary habitability implies that many other geophysical, geochemical, and astrophysical criteria must be met before an astronomical body can support life. In its astrobiology roadmap, NASA has defined the principal habitability criteria as "extended regions of liquid water,[1] conditions favorable for the assembly of complex organic molecules, and energy sources to sustain metabolism."[2]

In determining the habitability potential of a body, studies focus on its bulk composition, orbital properties, atmosphere, and potential chemical interactions. Stellar characteristics of importance include mass and luminosity, stable variability, and high metallicity. Rocky, wet terrestrial-type planets and moons with the potential for Earth-like chemistry are a primary focus of astrobiological research, although more speculative habitability theories occasionally examine alternative biochemistries and other types of astronomical bodies.

The idea that planets beyond Earth might host life is an ancient one, though historically it was framed by philosophy as much as physical science.[lower-alpha 1] The late 20th century saw two breakthroughs in the field. The observation and robotic spacecraft exploration of other planets and moons within the Solar System has provided critical information on defining habitability criteria and allowed for substantial geophysical comparisons between the Earth and other bodies. The discovery of extrasolar planets, beginning in the early 1990s[3][4] and accelerating thereafter, has provided further information for the study of possible extraterrestrial life. These findings confirm that the Sun is not unique among stars in hosting planets and expands the habitability research horizon beyond the Solar System.

The chemistry of life may have begun shortly after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago, during a habitable epoch when the Universe was only 10–17 million years old.[5][6] According to the panspermia hypothesis, microscopic life—distributed by meteoroids, asteroids and other small Solar System bodies—may exist throughout the Universe.[7] Nonetheless, Earth is the only place in the Universe known to harbor life.[8][9] Estimates of habitable zones around other stars,[10][11] along with the discovery of hundreds of extrasolar planets and new insights into the extreme habitats here on Earth, suggest that there may be many more habitable places in the Universe than considered possible until very recently.[12] On 4 November 2013, astronomers reported, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarfs within the Milky Way.[13][14] 11 billion of these estimated planets may be orbiting Sun-like stars.[15] The nearest such planet may be 12 light-years away, according to the scientists.[13][14]

Suitable star systems

An understanding of planetary habitability begins with the host star.[16] The classical HZ is defined for surface conditions only; but a metabolism that does not depend on the stellar light, can still exist outside the HZ, thriving in the interior of the planet where liquid water is available.[16]

Under the auspices of SETI's Project Phoenix, scientists Margaret Turnbull and Jill Tarter developed the "HabCat" (or Catalogue of Habitable Stellar Systems) in 2002. The catalogue was formed by winnowing the nearly 120,000 stars of the larger Hipparcos Catalogue into a core group of 17,000 "HabStars", and the selection criteria that were used provide a good starting point for understanding which astrophysical factors are necessary to habitable planets.[17] According to research published in August 2015, very large galaxies may be more favorable to the formation and development of habitable planets than smaller galaxies, like the Milky Way galaxy.[18]

However, the question of what makes a planet habitable is much more complex than having a planet located at the right distance from its host star so that water can be liquid on its surface: various geophysical and geodynamical aspects, the radiation, and the host stars plasma environment can influence the evolution of planets and life, if it originated.[16]

Spectral class

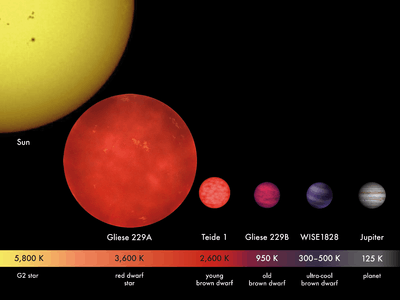

The spectral class of a star indicates its photospheric temperature, which (for main-sequence stars) correlates to overall mass. The appropriate spectral range for "HabStars" is considered to be "late F" or "G", to "mid-K". This corresponds to temperatures of a little more than 7,000 K down to a little more than 4,000 K (6,700 °C to 3,700 °C); the Sun, a G2 star at 5,777 K, is well within these bounds. "Middle-class" stars of this sort have a number of characteristics considered important to planetary habitability:

- They live at least a few billion years, allowing life a chance to evolve. More luminous main-sequence stars of the "O", "B", and "A" classes usually live less than a billion years and in exceptional cases less than 10 million.[19][lower-alpha 2]

- They emit enough high-frequency ultraviolet radiation to trigger important atmospheric dynamics such as ozone formation, but not so much that ionisation destroys incipient life.[20]

- Liquid water may exist on the surface of planets orbiting them at a distance that does not induce tidal locking. K Spectrum stars may be able to support life for long periods, far longer than the Sun.[21]

This spectral range probably accounts for between 5% and 10% of stars in the local Milky Way galaxy. Whether fainter late K and M class red dwarf stars are also suitable hosts for habitable planets is perhaps the most important open question in the entire field of planetary habitability given their prevalence (habitability of red dwarf systems). Gliese 581 c, a "super-Earth", has been found orbiting in the "habitable zone" (HZ) of a red dwarf and may possess liquid water. However it is also possible that a greenhouse effect may render it too hot to support life, while its neighbor, Gliese 581 d, may be a more likely candidate for habitability.[22] In September 2010, the discovery was announced of another planet, Gliese 581 g, in an orbit between these two planets. However, reviews of the discovery have placed the existence of this planet in doubt, and it is listed as "unconfirmed". In September 2012, the discovery of two planets orbiting Gliese 163[23] was announced.[24][25] One of the planets, Gliese 163 c, about 6.9 times the mass of Earth and somewhat hotter, was considered to be within the habitable zone.[24][25]

A recent study suggests that cooler stars that emit more light in the infrared and near infrared may actually host warmer planets with less ice and incidence of snowball states. These wavelengths are absorbed by their planets' ice and greenhouse gases and remain warmer.[26][27]

A stable habitable zone

The habitable zone is a shell-shaped region of space surrounding a star in which a planet could maintain liquid water on its surface.[16] The concept was first proposed by astrophysicist Su-Shu Huang in 1959, based on climatic constraints imposed by the host star.[16] After an energy source, liquid water is considered the most important ingredient for life, considering how integral it is to all life systems on Earth. This may reflect the known dependence of life on water; however, if life is discovered in the absence of water, the definition of an HZ may have to be greatly expanded.

The inner edge of the HZ is the distance where runaway greenhouse effect vaporize the whole water reservoir and, as a second effect, induce the photodissociation of water vapor and the loss of hydrogen to space. The outer edge of the HZ is the distance from the star where a maximum greenhouse effect fails to keep the surface of the planet above the freezing point.[16]

A "stable" HZ implies two factors. First, the range of an HZ should not vary greatly over time. All stars increase in luminosity as they age, and a given HZ thus migrates outwards, but if this happens too quickly (for example, with a super-massive star) planets may only have a brief window inside the HZ and a correspondingly smaller chance of developing life. Calculating an HZ range and its long-term movement is never straightforward, as negative feedback loops such as the CNO cycle will tend to offset the increases in luminosity. Assumptions made about atmospheric conditions and geology thus have as great an impact on a putative HZ range as does stellar evolution: the proposed parameters of the Sun's HZ, for example, have fluctuated greatly.[28]

Second, no large-mass body such as a gas giant should be present in or relatively close to the HZ, thus disrupting the formation of Earth-size bodies. The matter in the asteroid belt, for example, appears to have been unable to accrete into a planet due to orbital resonances with Jupiter; if the giant had appeared in the region that is now between the orbits of Venus and Mars, Earth would almost certainly not have developed in its present form. However a gas giant inside the HZ might have habitable moons under the right conditions.[29]

In the Solar System, the inner planets are terrestrial, and the outer ones are gas giants, but discoveries of extrasolar planets suggest that this arrangement may not be at all common: numerous Jupiter-sized bodies have been found in close orbit about their primary, disrupting potential HZs. However, present data for extrasolar planets is likely to be skewed towards that type (large planets in close orbits) because they are far easier to identify; thus it remains to be seen which type of planetary system is the norm, or indeed if there is one.

Low stellar variation

Changes in luminosity are common to all stars, but the severity of such fluctuations covers a broad range. Most stars are relatively stable, but a significant minority of variable stars often undergo sudden and intense increases in luminosity and consequently in the amount of energy radiated toward bodies in orbit. These stars are considered poor candidates for hosting life-bearing planets, as their unpredictability and energy output changes would negatively impact organisms: living things adapted to a specific temperature range could not survive too great a temperature variation. Further, upswings in luminosity are generally accompanied by massive doses of gamma ray and X-ray radiation which might prove lethal. Atmospheres do mitigate such effects, but their atmosphere might not be retained by planets orbiting variables, because the high-frequency energy buffeting these planets would continually strip them of their protective covering.

The Sun, in this respect as in many others, is relatively benign: the variation between its maximum and minimum energy output is roughly 0.1% over its 11-year solar cycle. There is strong (though not undisputed) evidence that even minor changes in the Sun's luminosity have had significant effects on the Earth's climate well within the historical era: the Little Ice Age of the mid-second millennium, for instance, may have been caused by a relatively long-term decline in the Sun's luminosity.[30] Thus, a star does not have to be a true variable for differences in luminosity to affect habitability. Of known solar analogs, one that closely resembles the Sun is considered to be 18 Scorpii; unfortunately for the prospects of life existing in its proximity, the only significant difference between the two bodies is the amplitude of the solar cycle, which appears to be much greater for 18 Scorpii.[31]

High metallicity

While the bulk of material in any star is hydrogen and helium, there is a significant variation in the amount of heavier elements (metals). A high proportion of metals in a star correlates to the amount of heavy material initially available in the protoplanetary disk. A smaller amount of metal makes the formation of planets much less likely, under the solar nebula theory of planetary system formation. Any planets that did form around a metal-poor star would probably be low in mass, and thus unfavorable for life. Spectroscopic studies of systems where exoplanets have been found to date confirm the relationship between high metal content and planet formation: "Stars with planets, or at least with planets similar to the ones we are finding today, are clearly more metal rich than stars without planetary companions."[32] This relationship between high metallicity and planet formation also means that habitable systems are more likely to be found around stars of younger generations, since stars that formed early in the universe's history have low metal content.

Planetary characteristics

The chief assumption about habitable planets is that they are terrestrial. Such planets, roughly within one order of magnitude of Earth mass, are primarily composed of silicate rocks, and have not accreted the gaseous outer layers of hydrogen and helium found on gas giants. Although the possibility that life could evolve in the cloud tops of giant planets has not been decisively ruled out,[lower-alpha 3] though it is considered unlikely, as they have no surface and their gravity is enormous.[36] The natural satellites of giant planets, meanwhile, remain valid candidates for hosting life.[33]

In February 2011 the Kepler Space Observatory Mission team released a list of 1235 extrasolar planet candidates, including 54 that may be in the habitable zone.[37][38] Six of the candidates in this zone are smaller than twice the size of Earth.[37] A more recent study found that one of these candidates (KOI 326.01) is much larger and hotter than first reported.[39] Based on the findings, the Kepler team estimated there to be "at least 50 billion planets in the Milky Way" of which "at least 500 million" are in the habitable zone.[40]

In analyzing which environments are likely to support life, a distinction is usually made between simple, unicellular organisms such as bacteria and archaea and complex metazoans (animals). Unicellularity necessarily precedes multicellularity in any hypothetical tree of life, and where single-celled organisms do emerge there is no assurance that greater complexity will then develop.[lower-alpha 4] The planetary characteristics listed below are considered crucial for life generally, but in every case multicellular organisms are more picky than unicellular life.

Mass

Low-mass planets are poor candidates for life for two reasons. First, their lesser gravity makes atmosphere retention difficult. Constituent molecules are more likely to reach escape velocity and be lost to space when buffeted by solar wind or stirred by collision. Planets without a thick atmosphere lack the matter necessary for primal biochemistry, have little insulation and poor heat transfer across their surfaces (for example, Mars, with its thin atmosphere, is colder than the Earth would be if it were at a similar distance from the Sun), and provide less protection against meteoroids and high-frequency radiation. Further, where an atmosphere is less dense than 0.006 Earth atmospheres, water cannot exist in liquid form as the required atmospheric pressure, 4.56 mm Hg (608 Pa) (0.18 inch Hg), does not occur. The temperature range at which water is liquid is smaller at low pressures generally.

Secondly, smaller planets have smaller diameters and thus higher surface-to-volume ratios than their larger cousins. Such bodies tend to lose the energy left over from their formation quickly and end up geologically dead, lacking the volcanoes, earthquakes and tectonic activity which supply the surface with life-sustaining material and the atmosphere with temperature moderators like carbon dioxide. Plate tectonics appear particularly crucial, at least on Earth: not only does the process recycle important chemicals and minerals, it also fosters bio-diversity through continent creation and increased environmental complexity and helps create the convective cells necessary to generate Earth's magnetic field.[41]

"Low mass" is partly a relative label: the Earth is low mass when compared to the Solar System's gas giants, but it is the largest, by diameter and mass, and the densest of all terrestrial bodies.[lower-alpha 5] It is large enough to retain an atmosphere through gravity alone and large enough that its molten core remains a heat engine, driving the diverse geology of the surface (the decay of radioactive elements within a planet's core is the other significant component of planetary heating). Mars, by contrast, is nearly (or perhaps totally) geologically dead and has lost much of its atmosphere.[42] Thus it would be fair to infer that the lower mass limit for habitability lies somewhere between that of Mars and that of Earth or Venus: 0.3 Earth masses has been offered as a rough dividing line for habitable planets.[43] However, a 2008 study by the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics suggests that the dividing line may be higher. Earth may in fact lie on the lower boundary of habitability: if it were any smaller, plate tectonics would be impossible. Venus, which has 85% of Earth's mass, shows no signs of tectonic activity. Conversely, "super-Earths", terrestrial planets with higher masses than Earth, would have higher levels of plate tectonics and thus be firmly placed in the habitable range.[44]

Exceptional circumstances do offer exceptional cases: Jupiter's moon Io (which is smaller than any of the terrestrial planets) is volcanically dynamic because of the gravitational stresses induced by its orbit, and its neighbor Europa may have a liquid ocean or icy slush underneath a frozen shell also due to power generated from orbiting a gas giant.

Saturn's Titan, meanwhile, has an outside chance of harbouring life, as it has retained a thick atmosphere and has liquid methane seas on its surface. Organic-chemical reactions that only require minimum energy are possible in these seas, but whether any living system can be based on such minimal reactions is unclear, and would seem unlikely. These satellites are exceptions, but they prove that mass, as a criterion for habitability, cannot necessarily be considered definitive at this stage of our understanding.

A larger planet is likely to have a more massive atmosphere. A combination of higher escape velocity to retain lighter atoms, and extensive outgassing from enhanced plate tectonics may greatly increase the atmospheric pressure and temperature at the surface compared to Earth. The enhanced greenhouse effect of such a heavy atmosphere would tend to suggest that the habitable zone should be further out from the central star for such massive planets.

Finally, a larger planet is likely to have a large iron core. This allows for a magnetic field to protect the planet from stellar wind and cosmic radiation, which otherwise would tend to strip away planetary atmosphere and to bombard living things with ionized particles. Mass is not the only criterion for producing a magnetic field—as the planet must also rotate fast enough to produce a dynamo effect within its core[45]—but it is a significant component of the process.

Orbit and rotation

As with other criteria, stability is the critical consideration in evaluating the effect of orbital and rotational characteristics on planetary habitability. Orbital eccentricity is the difference between a planet's farthest and closest approach to its parent star divided by the sum of said distances. It is a ratio describing the shape of the elliptical orbit. The greater the eccentricity the greater the temperature fluctuation on a planet's surface. Although they are adaptive, living organisms can stand only so much variation, particularly if the fluctuations overlap both the freezing point and boiling point of the planet's main biotic solvent (e.g., water on Earth). If, for example, Earth's oceans were alternately boiling and freezing solid, it is difficult to imagine life as we know it having evolved. The more complex the organism, the greater the temperature sensitivity.[46] The Earth's orbit is almost wholly circular, with an eccentricity of less than 0.02; other planets in the Solar System (with the exception of Mercury) have eccentricities that are similarly benign.

Data collected on the orbital eccentricities of extrasolar planets has surprised most researchers: 90% have an orbital eccentricity greater than that found within the Solar System, and the average is fully 0.25.[47] This means that the vast majority of planets have highly eccentric orbits and of these, even if their average distance from their star is deemed to be within the HZ, they nonetheless would be spending only a small portion of their time within the zone.

A planet's movement around its rotational axis must also meet certain criteria if life is to have the opportunity to evolve. A first assumption is that the planet should have moderate seasons. If there is little or no axial tilt (or obliquity) relative to the perpendicular of the ecliptic, seasons will not occur and a main stimulant to biospheric dynamism will disappear. The planet would also be colder than it would be with a significant tilt: when the greatest intensity of radiation is always within a few degrees of the equator, warm weather cannot move poleward and a planet's climate becomes dominated by colder polar weather systems.

If a planet is radically tilted, seasons will be extreme and make it more difficult for a biosphere to achieve homeostasis. The axial tilt of the Earth is higher now (in the Quaternary) than it has been in the past, coinciding with reduced polar ice, warmer temperatures and less seasonal variation. Scientists do not know whether this trend will continue indefinitely with further increases in axial tilt (see Snowball Earth).

The exact effects of these changes can only be computer modelled at present, and studies have shown that even extreme tilts of up to 85 degrees do not absolutely preclude life "provided it does not occupy continental surfaces plagued seasonally by the highest temperature."[48] Not only the mean axial tilt, but also its variation over time must be considered. The Earth's tilt varies between 21.5 and 24.5 degrees over 41,000 years. A more drastic variation, or a much shorter periodicity, would induce climatic effects such as variations in seasonal severity.

Other orbital considerations include:

- The planet should rotate relatively quickly so that the day-night cycle is not overlong. If a day takes years, the temperature differential between the day and night side will be pronounced, and problems similar to those noted with extreme orbital eccentricity will come to the fore.

- The planet also should rotate quickly enough so that a magnetic dynamo may be started in its iron core to produce a magnetic field.

- Change in the direction of the axis rotation (precession) should not be pronounced. In itself, precession need not affect habitability as it changes the direction of the tilt, not its degree. However, precession tends to accentuate variations caused by other orbital deviations; see Milankovitch cycles. Precession on Earth occurs over a 26,000-year cycle.

The Earth's Moon appears to play a crucial role in moderating the Earth's climate by stabilising the axial tilt. It has been suggested that a chaotic tilt may be a "deal-breaker" in terms of habitability—i.e. a satellite the size of the Moon is not only helpful but required to produce stability.[49] This position remains controversial.[lower-alpha 6]

Geochemistry

It is generally assumed that any extraterrestrial life that might exist will be based on the same fundamental biochemistry as found on Earth, as the four elements most vital for life, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, are also the most common chemically reactive elements in the universe. Indeed, simple biogenic compounds, such as very simple amino acids such as glycine, have been found in meteorites and in the interstellar medium.[50] These four elements together comprise over 96% of Earth's collective biomass. Carbon has an unparalleled ability to bond with itself and to form a massive array of intricate and varied structures, making it an ideal material for the complex mechanisms that form living cells. Hydrogen and oxygen, in the form of water, compose the solvent in which biological processes take place and in which the first reactions occurred that led to life's emergence. The energy released in the formation of powerful covalent bonds between carbon and oxygen, available by oxidizing organic compounds, is the fuel of all complex life-forms. These four elements together make up amino acids, which in turn are the building blocks of proteins, the substance of living tissue. In addition, neither sulfur, required for the building of proteins, nor phosphorus, needed for the formation of DNA, RNA, and the adenosine phosphates essential to metabolism, is rare.

Relative abundance in space does not always mirror differentiated abundance within planets; of the four life elements, for instance, only oxygen is present in any abundance in the Earth's crust.[51] This can be partly explained by the fact that many of these elements, such as hydrogen and nitrogen, along with their simplest and most common compounds, such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane, ammonia, and water, are gaseous at warm temperatures. In the hot region close to the Sun, these volatile compounds could not have played a significant role in the planets' geological formation. Instead, they were trapped as gases underneath the newly formed crusts, which were largely made of rocky, involatile compounds such as silica (a compound of silicon and oxygen, accounting for oxygen's relative abundance). Outgassing of volatile compounds through the first volcanoes would have contributed to the formation of the planets' atmospheres. The Miller–Urey experiment showed that, with the application of energy, simple inorganic compounds exposed to a primordial atmosphere can react to synthesize amino acids.[52]

Even so, volcanic outgassing could not have accounted for the amount of water in Earth's oceans.[53] The vast majority of the water —and arguably carbon— necessary for life must have come from the outer Solar System, away from the Sun's heat, where it could remain solid. Comets impacting with the Earth in the Solar System's early years would have deposited vast amounts of water, along with the other volatile compounds life requires onto the early Earth, providing a kick-start to the origin of life.

Thus, while there is reason to suspect that the four "life elements" ought to be readily available elsewhere, a habitable system probably also requires a supply of long-term orbiting bodies to seed inner planets. Without comets there is a possibility that life as we know it would not exist on Earth.

Microenvironments and extremophiles

One important qualification to habitability criteria is that only a tiny portion of a planet is required to support life. Astrobiologists often concern themselves with "micro-environments", noting that "we lack a fundamental understanding of how evolutionary forces, such as mutation, selection, and genetic drift, operate in micro-organisms that act on and respond to changing micro-environments."[54] Extremophiles are Earth organisms that live in niche environments under severe conditions generally considered inimical to life. Usually (although not always) unicellular, extremophiles include acutely alkaliphilic and acidophilic organisms and others that can survive water temperatures above 100 °C in hydrothermal vents.

The discovery of life in extreme conditions has complicated definitions of habitability, but also generated much excitement amongst researchers in greatly broadening the known range of conditions under which life can persist. For example, a planet that might otherwise be unable to support an atmosphere given the solar conditions in its vicinity, might be able to do so within a deep shadowed rift or volcanic cave.[55] Similarly, craterous terrain might offer a refuge for primitive life. The Lawn Hill crater has been studied as an astrobiological analog, with researchers suggesting rapid sediment infill created a protected microenvironment for microbial organisms; similar conditions may have occurred over the geological history of Mars.[56]

Earth environments that cannot support life are still instructive to astrobiologists in defining the limits of what organisms can endure. The heart of the Atacama desert, generally considered the driest place on Earth, appears unable to support life, and it has been subject to study by NASA and ESA for that reason: it provides a Mars analog and the moisture gradients along its edges are ideal for studying the boundary between sterility and habitability.[57] The Atacama was the subject of study in 2003 that partly replicated experiments from the Viking landings on Mars in the 1970s; no DNA could be recovered from two soil samples, and incubation experiments were also negative for biosignatures.[58]

Ecological factors

The two current ecological approaches for predicting the potential habitability use 19 or 20 environmental factors, with emphasis on water availability, temperature, presence of nutrients, an energy source, and protection from solar ultraviolet and galactic cosmic radiation.[59][60]

| Some habitability factors[60] | |

|---|---|

| Water | · Activity of liquid water · Past or future liquid (ice) inventories · Salinity, pH, and Eh of available water |

| Chemical environment | Nutrients: · C, H, N, O, P, S, essential metals, essential micronutrients · Fixed nitrogen · Availability/mineralogy Toxin abundances and lethality: · Heavy metals (e.g. Zn, Ni, Cu, Cr, As, Cd, etc.; some are essential, but toxic at high levels) · Globally distributed oxidizing soils |

| Energy for metabolism | Solar (surface and near-surface only) Geochemical (subsurface) · Oxidants · Reductants · Redox gradients |

| Conducive physical conditions | · Temperature · Extreme diurnal temperature fluctuations · Low pressure (is there a low-pressure threshold for terrestrial anaerobes?) · Strong ultraviolet germicidal irradiation · Galactic cosmic radiation and solar particle events (long-term accumulated effects) · Solar UV-induced volatile oxidants, e.g. O 2−, O−, H2O2, O3 · Climate and its variability (geography, seasons, diurnal, and eventually, obliquity variations) · Substrate (soil processes, rock microenvironments, dust composition, shielding) · High CO2 concentrations in the global atmosphere · Transport (aeolian, ground water flow, surface water, glacial) |

Alternative star systems

In determining the feasibility of extraterrestrial life, astronomers had long focused their attention on stars like the Sun. However, since planetary systems that resemble the Solar System are proving to be rare, they have begun to explore the possibility that life might form in systems very unlike our own.

Binary systems

Typical estimates often suggest that 50% or more of all stellar systems are binary systems. This may be partly sample bias, as massive and bright stars tend to be in binaries and these are most easily observed and catalogued; a more precise analysis has suggested that the more common fainter stars are usually singular, and that up to two thirds of all stellar systems are therefore solitary.[61]

The separation between stars in a binary may range from less than one astronomical unit (AU, the average Earth–Sun distance) to several hundred. In latter instances, the gravitational effects will be negligible on a planet orbiting an otherwise suitable star and habitability potential will not be disrupted unless the orbit is highly eccentric (see Nemesis, for example). However, where the separation is significantly less, a stable orbit may be impossible. If a planet's distance to its primary exceeds about one fifth of the closest approach of the other star, orbital stability is not guaranteed.[62] Whether planets might form in binaries at all had long been unclear, given that gravitational forces might interfere with planet formation. Theoretical work by Alan Boss at the Carnegie Institution has shown that gas giants can form around stars in binary systems much as they do around solitary stars.[63]

One study of Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to the Sun, suggested that binaries need not be discounted in the search for habitable planets. Centauri A and B have an 11 AU distance at closest approach (23 AU mean), and both should have stable habitable zones. A study of long-term orbital stability for simulated planets within the system shows that planets within approximately three AU of either star may remain rather stable (i.e. the semi-major axis deviating by less than 5% during 32 000 binary periods). The HZ for Centauri A is conservatively estimated at 1.2 to 1.3 AU and Centauri B at 0.73 to 0.74—well within the stable region in both cases.[64]

Red dwarf systems

Determining the habitability of red dwarf stars could help determine how common life in the universe might be, as red dwarfs make up between 70 and 90% of all the stars in the galaxy.

Size

Astronomers for many years ruled out red dwarfs as potential abodes for life. Their small size (from 0.08 to 0.45 solar masses) means that their nuclear reactions proceed exceptionally slowly, and they emit very little light (from 3% of that produced by the Sun to as little as 0.01%). Any planet in orbit around a red dwarf would have to huddle very close to its parent star to attain Earth-like surface temperatures; from 0.3 AU (just inside the orbit of Mercury) for a star like Lacaille 8760, to as little as 0.032 AU for a star like Proxima Centauri[65] (such a world would have a year lasting just 6.3 days). At those distances, the star's gravity would cause tidal locking. One side of the planet would eternally face the star, while the other would always face away from it. The only ways in which potential life could avoid either an inferno or a deep freeze would be if the planet had an atmosphere thick enough to transfer the star's heat from the day side to the night side, or if there was a gas giant in the habitable zone, with a habitable moon, which would be locked to the planet instead of the star, allowing a more even distribution of radiation over the planet. It was long assumed that such a thick atmosphere would prevent sunlight from reaching the surface in the first place, preventing photosynthesis.

This pessimism has been tempered by research. Studies by Robert Haberle and Manoj Joshi of NASA's Ames Research Center in California have shown that a planet's atmosphere (assuming it included greenhouse gases CO2 and H2O) need only be 100 mbs, or 10% of Earth's atmosphere, for the star's heat to be effectively carried to the night side.[66] This is well within the levels required for photosynthesis, though water would still remain frozen on the dark side in some of their models. Martin Heath of Greenwich Community College, has shown that seawater, too, could be effectively circulated without freezing solid if the ocean basins were deep enough to allow free flow beneath the night side's ice cap. Further research—including a consideration of the amount of photosynthetically active radiation—suggested that tidally locked planets in red dwarf systems might at least be habitable for higher plants.[67]

Other factors limiting habitability

Size is not the only factor in making red dwarfs potentially unsuitable for life, however. On a red dwarf planet, photosynthesis on the night side would be impossible, since it would never see the sun. On the day side, because the sun does not rise or set, areas in the shadows of mountains would remain so forever. Photosynthesis as we understand it would be complicated by the fact that a red dwarf produces most of its radiation in the infrared, and on the Earth the process depends on visible light. There are potential positives to this scenario. Numerous terrestrial ecosystems rely on chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis, for instance, which would be possible in a red dwarf system. A static primary star position removes the need for plants to steer leaves toward the sun, deal with changing shade/sun patterns, or change from photosynthesis to stored energy during night. Because of the lack of a day-night cycle, including the weak light of morning and evening, far more energy would be available at a given radiation level.

Red dwarfs are far more variable and violent than their more stable, larger cousins. Often they are covered in starspots that can dim their emitted light by up to 40% for months at a time, while at other times they emit gigantic flares that can double their brightness in a matter of minutes.[68] Such variation would be very damaging for life, as it would not only destroy any complex organic molecules that could possibly form biological precursors, but also because it would blow off sizeable portions of the planet's atmosphere.

For a planet around a red dwarf star to support life, it would require a rapidly rotating magnetic field to protect it from the flares. A tidally locked planet rotates only very slowly, and so cannot produce a geodynamo at its core. The violent flaring period of a red dwarf's life cycle is estimated to only last roughly the first 1.2 billion years of its existence. If a planet forms far away from a red dwarf so as to avoid tidal locking, and then migrates into the star's habitable zone after this turbulent initial period, it is possible that life may have a chance to develop.[69] However, given its age, at 7–12 billion years of age, Barnard's Star is considerably older than the Sun. It was long assumed to be quiescent in terms of stellar activity. Yet, in 1998, astronomers observed an intense stellar flare, surprisingly showing that Barnard's Star is, despite its age, a flare star.[70]

Longevity and ubiquity

There is, however, one major advantage that red dwarfs have over other stars as abodes for life: they live a long time. It took 4.5 billion years before humanity appeared on Earth, and life as we know it will see suitable conditions for 1[71] to 2.3[72] billion years more. Red dwarfs, by contrast, could live for trillions of years because their nuclear reactions are far slower than those of larger stars, meaning that life would have longer to evolve and survive.

While the odds of finding a planet in the habitable zone around any specific red dwarf are slim, the total amount of habitable zone around all red dwarfs combined is equal to the total amount around Sun-like stars given their ubiquity.[73] Furthermore, this total amount of habitable zone will last longer, because red dwarf stars live for hundreds of billions of years or even longer on the main sequence.[74]

Massive stars

Recent research suggests that very large stars, greater than ~100 solar masses, could have planetary systems consisting of hundreds of Mercury-sized planets within the habitable zone. Such systems could also contain brown dwarfs and low-mass stars (~0.1–0.3 solar masses).[75] However the very short lifespans of stars of more than a few solar masses would scarcely allow time for a planet to cool, let alone the time needed for a stable biosphere to develop. Massive stars are thus eliminated as possible abodes for life.[76]

However, a massive-star system could be a progenitor of life in another way – the supernova explosion of the massive star in the central part of the system. This supernova will disperse heavier elements throughout its vicinity, created during the phase when the massive star has moved off of the main sequence, and the systems of the potential low-mass stars (which are still on the main sequence) within the former massive-star system may be enriched with the relatively large supply of the heavy elements so close to a supernova explosion. However, this states nothing about what types of planets would form as a result of the supernova material, or what their habitability potential would be.

Four classes of habitable planets

In a review of the factors which are important for the evolution of habitable Earth-sized planets, Lammer et al. proposed a classification of four water-dependant habitat types: [16][77]

Class I habitats are planetary bodies on which stellar and geophysical conditions allow liquid water to be available at the surface, along with sunlight, so that complex multicellular organisms may originate.

Class II habitats include bodies which initially enjoy Earth-like conditions, but do not keep their ability to sustain liquid water on their surface due to stellar or geophysical conditions. Mars, and possibly Venus are examples of this class where complex life forms may not develop.

Class III habitats are planetary bodies where water liquid water oceans exist below the surface, where they can interact directly with a silicate-rich core.

- Such a situation can be expected on water-rich planets located too far from their star to allow surface liquid water, but on which subsurface water is in liquid form because of the geothermal heat. Two examples of such an environment are Europa and Enceladus. In such worlds, not only is light not available as an energy source, but the organic material brought by meteorites (thought to have been necessary to start life in some scenarios) may not easily reach the liquid water. If a planet can only harbor life below its surface, the biosphere would not likely modify the whole planetary environment in an observable way, thus, detecting its presence on an exoplanet would be extremely difficult.

Class IV habitats have liquid water layers between two ice layers, or liquids above ice.

- If the water layer is thick enough, water at its base will be in solid phase (ice polymorphs) because of the high pressure. Ganymede and Callisto are likely examples of this class. Their oceans are thought to be enclosed between thick ice layers. In such conditions, the emergence of even simple life forms may be very difficult because the necessary ingredients for life will likely be completely diluted.

The galactic neighborhood

Along with the characteristics of planets and their star systems, the wider galactic environment may also impact habitability. Scientists considered the possibility that particular areas of galaxies (galactic habitable zones) are better suited to life than others; the Solar System in which we live, in the Orion Spur, on the Milky Way galaxy's edge is considered to be in a life-favorable spot:[78]

- It is not in a globular cluster where immense star densities are inimical to life, given excessive radiation and gravitational disturbance. Globular clusters are also primarily composed of older, probably metal-poor, stars. Furthermore, in globular clusters, the great ages of the stars would mean a large amount of stellar evolution by the host or other nearby stars, which due to their proximity may cause extreme harm to life on any planets, provided that they can form.

- It is not near an active gamma ray source.

- It is not near the galactic center where once again star densities increase the likelihood of ionizing radiation (e.g., from magnetars and supernovae). A supermassive black hole is also believed to lie at the middle of the galaxy which might prove a danger to any nearby bodies.

- The circular orbit of the Sun around the galactic center keeps it out of the way of the galaxy's spiral arms where intense radiation and gravitation may again lead to disruption.[79]

Thus, relative isolation is ultimately what a life-bearing system needs. If the Sun were crowded amongst other systems, the chance of being fatally close to dangerous radiation sources would increase significantly. Further, close neighbors might disrupt the stability of various orbiting bodies such as Oort cloud and Kuiper belt objects, which can bring catastrophe if knocked into the inner Solar System.

While stellar crowding proves disadvantageous to habitability, so too does extreme isolation. A star as metal-rich as the Sun would probably not have formed in the very outermost regions of the Milky Way given a decline in the relative abundance of metals and a general lack of star formation. Thus, a "suburban" location, such as the Solar System enjoys, is preferable to a Galaxy's center or farthest reaches.[80]

Other considerations

Alternative biochemistries

While most investigations of extraterrestrial life start with the assumption that advanced life-forms must have similar requirements for life as on Earth, the hypothesis of other types of biochemistry suggests the possibility of lifeforms evolving around a different metabolic mechanism. In Evolving the Alien, biologist Jack Cohen and mathematician Ian Stewart argue astrobiology, based on the Rare Earth hypothesis, is restrictive and unimaginative. They suggest that Earth-like planets may be very rare, but non-carbon-based complex life could possibly emerge in other environments. The most frequently mentioned alternative to carbon is silicon-based life, while ammonia and hydrocarbons are sometimes suggested as alternative solvents to water. The astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch and other scientists have proposed a Planet Habitability Index whose criteria include "potential for holding a liquid solvent" that is not necessarily restricted to water.[81][82]

More speculative ideas have focused on bodies altogether different from Earth-like planets. Astronomer Frank Drake, a well-known proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life, imagined life on a neutron star: submicroscopic "nuclear molecules" combining to form creatures with a life cycle millions of times quicker than Earth life.[83] Called "imaginative and tongue-in-cheek", the idea gave rise to science fiction depictions.[84] Carl Sagan, another optimist with regards to extraterrestrial life, considered the possibility of organisms that are always airborne within the high atmosphere of Jupiter in a 1976 paper.[34][35] Cohen and Stewart also envisioned life in both a solar environment and in the atmosphere of a gas giant.

"Good Jupiters"

"Good Jupiters" are gas giants, like the Solar System's Jupiter, that orbit their stars in circular orbits far enough away from the habitable zone not to disturb it but close enough to "protect" terrestrial planets in closer orbit in two critical ways. First, they help to stabilize the orbits, and thereby the climates of the inner planets. Second, they keep the inner stellar system relatively free of comets and asteroids that could cause devastating impacts.[85] Jupiter orbits the Sun at about five times the distance between the Earth and the Sun. This is the rough distance we should expect to find good Jupiters elsewhere. Jupiter's "caretaker" role was dramatically illustrated in 1994 when Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 impacted the giant.

However, the evidence is not quite so clear. Research has shown that Jupiter's role in determining the rate at which objects hit Earth is significantly more complicated than once thought.[86][87][88][89]

The role of Jupiter in the early history of the Solar System is somewhat better established, and the source of significantly less debate. Early in the Solar System's history, Jupiter is accepted as having played an important role in the hydration of our planet: it increased the eccentricity of asteroid belt orbits and enabled many to cross Earth's orbit and supply the planet with important volatiles such as water and carbon dioxide. Before Earth reached half its present mass, icy bodies from the Jupiter–Saturn region and small bodies from the primordial asteroid belt supplied water to the Earth due to the gravitational scattering of Jupiter and, to a lesser extent, Saturn.[90] Thus, while the gas giants are now helpful protectors, they were once suppliers of critical habitability material.

In contrast, Jupiter-sized bodies that orbit too close to the habitable zone but not in it (as in 47 Ursae Majoris), or have a highly elliptical orbit that crosses the habitable zone (like 16 Cygni B) make it very difficult for an independent Earth-like planet to exist in the system. See the discussion of a stable habitable zone above. However, during the process of migrating into a habitable zone, a Jupiter-size planet may capture a terrestrial planet as a moon. Even if such a planet is initially loosely bound and following a strongly inclined orbit, gravitational interactions with the star can stabilize the new moon into a close, circular orbit that is coplanar with the planet's orbit around the star.[91]

Life's impact on habitability

A supplement to the factors that support life's emergence is the notion that life itself, once formed, becomes a habitability factor in its own right. An important Earth example was the production of molecular oxygen gas (O

2) by ancient cyanobacteria, and eventually photosynthesizing plants, leading to a radical change in the composition of Earth's atmosphere. This environmental change is called the Great Oxygenation Event. This oxygen proved fundamental to the respiration of later animal species. The Gaia hypothesis, a scientific model of the geo-biosphere pioneered by James Lovelock in 1975, argues that life as a whole fosters and maintains suitable conditions for itself by helping to create a planetary environment suitable for its continuity. Similarly, David Grinspoon has suggested a "living worlds hypothesis" in which our understanding of what constitutes habitability cannot be separated from life already extant on a planet. Planets that are geologically and meteorologically alive are much more likely to be biologically alive as well and "a planet and its life will co-evolve."[92] This is the basis of Earth system science.

See also

- Circumstellar habitable zone

- Class M planet (fiction)

- Darwin (spacecraft)

- Earth analog

- Exoplanetology

- Extraterrestrial liquid water

- Habitability of natural satellites

- Habitable Planets for Man

- List of potentially habitable exoplanets

- Neocatastrophism

- Rare Earth hypothesis

- Space colonization

- Superhabitable planet

- Terraforming

- Terrestrial Planet Finder

Notes

- ↑ This article is an analysis of planetary habitability from the perspective of contemporary physical science. A historical viewpoint on the possibility of habitable planets can be found at Beliefs in extraterrestrial life and Cosmic pluralism. For a discussion of the probability of alien life see the Drake equation and Fermi paradox. Habitable planets are also a staple of fiction; see Planets in science fiction.

- ↑ Life appears to have emerged on Earth approximately 500 million years after the planet's formation. "A" class stars (which shine for between 600 million and 1.2 billion years) and a small fraction of "B" class stars (which shine 10+ million to 600 million) fall within this window. At least theoretically life could emerge in such systems but it would almost certainly not reach a sophisticated level given these time-frames and the fact that increases in luminosity would occur quite rapidly. Life around "O" class stars is exceptionally unlikely, as they shine for less than ten million years.

- ↑ In Evolving the Alien, Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart evaluate plausible scenarios in which life might form in the cloud-tops of Jovian planets. Similarly, Carl Sagan suggested that the clouds of Jupiter might host life.[34][35]

- ↑ There is an emerging consensus that single-celled micro-organisms may in fact be common in the universe, especially since Earth's extremophiles flourish in environments that were once considered hostile to life. The potential occurrence of complex multi-celled life remains much more controversial. In their work Rare Earth: Why Complex Life Is Uncommon in the Universe, Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee argue that microbial life is probably widespread while complex life is very rare and perhaps even unique to Earth. Current knowledge of Earth's history partly buttresses this theory: multi-celled organisms are believed to have emerged at the time of the Cambrian explosion close to 600 million years ago, but more than 3 billion years after life first appeared. That Earth life remained unicellular for so long underscores that the decisive step toward complex organisms need not necessarily occur.

- ↑ There is a "mass-gap" in the Solar System between Earth and the two smallest gas giants, Uranus and Neptune, which are 13 and 17 Earth masses. This is probably just chance, as there is no geophysical barrier to the formation of intermediate bodies (see for instance OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb and Super-Earth) and we should expect to find planets throughout the galaxy between two and twelve Earth masses. If the star system is otherwise favorable, such planets would be good candidates for life as they would be large enough to remain internally dynamic and to retain an atmosphere for billions of years but not so large as to accrete a gaseous shell which limits the possibility of life formation.

- ↑ According to prevailing theory, the formation of the Moon commenced when a Mars-sized body struck the Earth in a glancing collision late in its formation, and the ejected material coalesced and fell into orbit (see giant impact hypothesis). In Rare Earth Ward and Brownlee emphasize that such impacts ought to be rare, reducing the probability of other Earth-Moon type systems and hence the probability of other habitable planets. Other moon formation processes are possible, however, and the proposition that a planet may be habitable in the absence of a moon has not been disproven.

References

- 1 2 Dyches, Preston; Chou, Felcia (7 April 2015). "The Solar System and Beyond is Awash in Water". NASA. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Goal 1: Understand the nature and distribution of habitable environments in the Universe". Astrobiology: Roadmap. NASA. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ↑ Wolszczan, A.; Frail, D. A. (9 January 1992). "A planetary system around the millisecond pulsar PSR1257 + 12". Nature. 355 (6356): 145–147. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..145W. doi:10.1038/355145a0.

- ↑ Wolszczan, A (1994). "Confirmation of Earth Mass Planets Orbiting the Millisecond Pulsar PSR:B1257+12". Science. 264 (5158): 538–42. Bibcode:1994Sci...264..538W. doi:10.1126/science.264.5158.538. JSTOR 2883699. PMID 17732735.

- ↑ Loeb, Abraham (October 2014). "The Habitable Epoch of the Early Universe". International Journal of Astrobiology. 13 (04): 337–339. arXiv:1312.0613

. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..337L. doi:10.1017/S1473550414000196.

. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..337L. doi:10.1017/S1473550414000196. - ↑ Dreifus, Claudia (2 December 2014). "Much-Discussed Views That Go Way Back – Avi Loeb Ponders the Early Universe, Nature and Life". New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ↑ Rampelotto, P.H. (2010). "Panspermia: A Promising Field Of Research" (PDF). Astrobiology Science Conference. Retrieved 3 December 2014. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ Graham, Robert W. (February 1990). "NASA Technical Memorandum 102363 – Extraterrestrial Life in the Universe" (PDF). NASA. Lewis Research Center, Ohio. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ↑ Altermann, Wladyslaw (2008). "From Fossils to Astrobiology – A Roadmap to Fata Morgana?". In Seckbach, Joseph; Walsh, Maud. From Fossils to Astrobiology: Records of Life on Earth and the Search for Extraterrestrial Biosignatures. 12. p. xvii. ISBN 1-4020-8836-1.

- ↑ Horneck, Gerda; Petra Rettberg (2007). Complete Course in Astrobiology. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-40660-3.

- ↑ Davies, Paul (18 November 2013). "Are We Alone in the Universe?". New York Times. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (6 January 2015). "As Ranks of Goldilocks Planets Grow, Astronomers Consider What's Next". New York Times. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- 1 2 Overbye, Dennis (4 November 2013). "Far-Off Planets Like the Earth Dot the Galaxy". New York Times. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- 1 2 Petigura, Eric A.; Howard, Andrew W.; Marcy, Geoffrey W. (31 October 2013). "Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110: 19273–19278. arXiv:1311.6806

. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019273P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319909110. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019273P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319909110. Retrieved 5 November 2013. - ↑ Khan, Amina (4 November 2013). "Milky Way may host billions of Earth-size planets". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lammer, H.; Bredehöft, J. H.; Coustenis, A.; Khodachenko, M. L.; et al. (2009). "What makes a planet habitable?" (PDF). The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 17: 181–249. Bibcode:2009A&ARv..17..181L. doi:10.1007/s00159-009-0019-z. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

- ↑ Turnbull, Margaret C.; Tarter, Jill C. (March 2003). "Target selection for SETI: A catalog of nearby habitable stellar systems" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 145: 181–198. arXiv:astro-ph/0210675

. Bibcode:2003ApJS..145..181T. doi:10.1086/345779. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2006. Habitability criteria defined—the foundational source for this article.

. Bibcode:2003ApJS..145..181T. doi:10.1086/345779. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2006. Habitability criteria defined—the foundational source for this article. - ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (21 August 2015). "Giant Galaxies May Be Better Cradles for Habitable Planets". Space.com. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ "Star tables". California State University, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ Kasting, James F.; Whittet, DC; Sheldon, WR (August 1997). "Ultraviolet radiation from F and K stars and implications for planetary habitability". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 27 (4): 413–420. doi:10.1023/A:1006596806012. PMID 11536831.

- ↑ Guinan, Edward; Cuntz, Manfred (10 August 2009). "The violent youth of solar proxies steer course of genesis of life". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ↑ "Gliese 581: one planet might indeed be habitable" (Press release). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ↑ Staff (20 September 2012). "LHS 188 – High proper-motion Star". Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg (Strasbourg astronomical Data Center). Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- 1 2 Méndez, Abel (29 August 2012). "A Hot Potential Habitable Exoplanet around Gliese 163". University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo (Planetary Habitability Laboratory). Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- 1 2 Redd, Nola Taylor (20 September 2012). "Newfound Alien Planet a Top Contender to Host Life". Space.com. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ↑ "Planets May Keep Warmer In A Cool Star System". Redorbit. 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Shields, A. L.; Meadows, V. S.; Bitz, C. M.; Pierrehumbert, R. T.; Joshi, M. M.; Robinson, T. D. (2013). "The Effect of Host Star Spectral Energy Distribution and Ice-Albedo Feedback on the Climate of Extrasolar Planets". Astrobiology. 13 (8): 715–39. arXiv:1305.6926

. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..715S. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0961. PMID 23855332.

. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..715S. doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0961. PMID 23855332. - ↑ Kasting, James F.; Whitmore, Daniel P.; Reynolds, Ray T. (1993). "Habitable Zones Around Main Sequence Stars" (PDF). Icarus. 101 (1): 108–128. Bibcode:1993Icar..101..108K. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1010. PMID 11536936. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ Williams, Darren M.; Kasting, James F.; Wade, Richard A. (January 1997). "Habitable moons around extrasolar giant planets". Nature. 385 (6613): 234–236. Bibcode:1996DPS....28.1221W. doi:10.1038/385234a0. PMID 9000072.

- ↑ "The Little Ice Age". Department of Atmospheric Science. University of Washington. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "18 Scorpii". www.solstation.com. Sol Company. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Santos, Nuno C.; Israelian, Garik; Mayor, Michael (2003). "Confirming the Metal-Rich Nature of Stars with Giant Planets" (PDF). Proceedings of 12th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems, and The Sun. University of Colorado. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- 1 2 "An interview with Dr. Darren Williams". Astrobiology: The Living Universe. 2000. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- 1 2 Sagan, C.; Salpeter, E. E. (1976). "Particles, environments, and possible ecologies in the Jovian atmosphere". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 32: 737. Bibcode:1976ApJS...32..737S. doi:10.1086/190414.

- 1 2 Darling, David. "Jupiter, life on". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ "Could there be life in the outer solar system?". Millennium Mathematics Project, Videoconferences for Schools. University of Cambridge. 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- 1 2 Borucki, William J.; Koch, David G.; Basri, Gibor; Batalha, Natalie; Brown, Timothy M.; Bryson, Stephen T.; Caldwell, Douglas; Christensen-Dalsgaard, Jørgen; Cochran, William D.; Devore, Edna; Dunham, Edward W.; Gautier, Thomas N.; Geary, John C.; Gilliland, Ronald; Gould, Alan; Howell, Steve B.; Jenkins, Jon M.; Latham, David W.; Lissauer, Jack J.; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; Rowe, Jason; Sasselov, Dimitar; Boss, Alan; Charbonneau, David; Ciardi, David; Doyle, Laurance; Dupree, Andrea K.; Ford, Eric B.; Fortney, Jonathan; et al. (2011). "Characteristics of planetary candidates observed by Kepler, II: Analysis of the first four months of data". The Astrophysical Journal. 736 (1): 19. arXiv:1102.0541

. Bibcode:2011ApJ...736...19B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/1/19.

. Bibcode:2011ApJ...736...19B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/1/19. - ↑ "NASA Finds Earth-size Planet Candidates in Habitable Zone, Six Planet System". NASA. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ Grant, Andrew (8 March 2011). "Exclusive: "Most Earth-Like" Exoplanet Gets Major Demotion—It Isn't Habitable". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (19 February 2011). "Cosmic census finds crowd of planets in our galaxy". Associated Press. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ↑ Ward, pp. 191–220

- ↑ "The Heat History of the Earth". Geolab. James Madison University. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Raymond, Sean N.; Quinn, Thomas; Lunine, Jonathan I. (January 2007). "High-resolution simulations of the final assembly of Earth-like planets 2: water delivery and planetary habitability". Astrobiology. 7 (1): 66–84. arXiv:astro-ph/0510285

. Bibcode:2007AsBio...7...66R. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.06-0126. PMID 17407404.

. Bibcode:2007AsBio...7...66R. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.06-0126. PMID 17407404. - ↑ "Earth: A Borderline Planet for Life?". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ↑ Nave, C. R. "Magnetic Field of the Earth". HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Ward, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Bortman, Henry (22 June 2005). "Elusive Earths". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "Planetary Tilt Not A Spoiler For Habitation" (Press release). Penn State University. 25 August 2003. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Lasker, J.; Joutel, F.; Robutel, P. (July 1993). "Stabilization of the earth's obliquity by the moon". Nature. 361 (6413): 615–617. Bibcode:1993Natur.361..615L. doi:10.1038/361615a0.

- ↑ "Organic Molecule, Amino Acid-Like, Found In Constellation Sagittarius". ScienceDaily. 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ↑ Darling, David. "Elements, biological abundance". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "How did chemistry and oceans produce this?". The Electronic Universe Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "How did the Earth Get to Look Like This?". The Electronic Universe Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ "Understand the evolutionary mechanisms and environmental limits of life". Astrobiology: Roadmap. NASA. September 2003. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ Hart, Stephen (17 June 2003). "Cave Dwellers: ET Might Lurk in Dark Places". Space.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2003. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ Lindsay, J; Brasier, M (2006). "Impact Craters as biospheric microenvironments, Lawn Hill Structure, Northern Australia". Astrobiology. 6 (2): 348–363. Bibcode:2006AsBio...6..348L. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.6.348. PMID 16689651.

- ↑ McKay, Christopher (June 2002). "Too Dry for Life: The Atacama Desert and Mars" (PDF). Ames Research Center. NASA. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ↑ Navarro-González, Rafael; McKay, Christopher P. (7 November 2003). "Mars-Like Soils in the Atacama Desert, Chile, and the Dry Limit of Microbial Life". Science. 302 (5647): 1018–1021. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1018N. doi:10.1126/science.1089143. PMID 14605363.

- ↑ Schuerger, Andrew C.; Golden, D.C.; Ming, Doug W. (November 2012). "Biotoxicity of Mars soils: 1. Dry deposition of analog soils on microbial colonies and survival under Martian conditions". Planetary and Space Science. 72 (1): 91–101. Bibcode:2012P&SS...72...91S. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2012.07.026.

- 1 2 Beaty, David W.; et al. (14 July 2006), "MEPAG SR-SAG (2006) Unpublished white paper", in the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG), Findings of the Mars Special Regions Science Analysis Group (PDF), Jet Propulsion Laboratory – NASA, p. 17, retrieved 6 June 2013

- ↑ "Most Milky Way Stars Are Single" (Press release). Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 30 January 2006. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ↑ "Stars and Habitable Planets". www.solstation.com. Sol Company. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ↑ Boss, Alan (January 2006). "Planetary Systems can from around Binary Stars" (Press release). Carnegie Institution. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ↑ Wiegert, Paul A.; Holman, Matt J. (April 1997). "The stability of planets in the Alpha Centauri system". The Astronomical Journal. 113 (4): 1445–1450. arXiv:astro-ph/9609106

. Bibcode:1997AJ....113.1445W. doi:10.1086/118360.

. Bibcode:1997AJ....113.1445W. doi:10.1086/118360. - ↑ "Habitable zones of stars". NASA Specialized Center of Research and Training in Exobiology. University of Southern California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 21 November 2000. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Joshi, M. M.; Haberle, R. M.; Reynolds, R. T. (October 1997). "Simulations of the Atmospheres of Synchronously Rotating Terrestrial Planets Orbiting M Dwarfs: Conditions for Atmospheric Collapse and the Implications for Habitability" (PDF). Icarus. 129 (2): 450–465. Bibcode:1997Icar..129..450J. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5793.

- ↑ Heath, Martin J.; Doyle, Laurance R.; Joshi, Manoj M.; Haberle, Robert M. (1999). "Habitability of Planets Around Red Dwarf Stars" (PDF). Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere. 29 (4): 405–424. doi:10.1023/A:1006596718708. PMID 10472629. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ↑ Croswell, Ken (27 January 2001). "Red, willing and able" (Full reprint). New Scientist. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Cain, Fraser; Gay, Pamela (2007). "AstronomyCast episode 40: American Astronomical Society Meeting, May 2007". Universe Today. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- ↑ Croswell, Ken (November 2005). "A Flare for Barnard's Star". Astronomy Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing Co. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Hines, Sandra (13 January 2003). "'The end of the world' has already begun, UW scientists say" (Press release). University of Washington. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ↑ Li, King-Fai; Pahlevan, Kaveh; Kirschvink, Joseph L.; Yung, Yuk L. (2009). "Atmospheric pressure as a natural climate regulator for a terrestrial planet with a biosphere" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (24): 9576–9579. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9576L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809436106. PMC 2701016

. PMID 19487662. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

. PMID 19487662. Retrieved 19 July 2009. - ↑ "M Dwarfs: The Search for Life is On, Interview with Todd Henry". Astrobiology Magazine. 29 August 2005. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Cain, Fraser (4 February 2009). "Red Dwarf Stars". Universe Today.

- ↑ Kashi, Amit; Soker, Noam (2011). "The outcome of the protoplanetary disk of very massive stars, January 2011". New Astronomy. 16: 27–32. arXiv:1002.4693

. Bibcode:2011NewA...16...27K. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2010.06.003.

. Bibcode:2011NewA...16...27K. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2010.06.003. - ↑ Stellar mass#Age

- ↑ Forget, François (July 2013). "On the probability of habitable planets" (PDF). International Joural of Astrobiology”. 12 (3): 177–185. arXiv:1212.0113

. Bibcode:2013IJAsB..12..177F. doi:10.1017/S1473550413000128. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

. Bibcode:2013IJAsB..12..177F. doi:10.1017/S1473550413000128. Retrieved 2016-05-04. - ↑ Mullen, Leslie (18 May 2001). "Galactic Habitable Zones". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Ward, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Dorminey, Bruce (July 2005). "Dark Threat". Astronomy. 33: 40–45. Bibcode:2005Ast....33g..40D.

- ↑ Alan Boyle (2011-11-22). "Which alien worlds are most livable?". NBC News. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- ↑ Dirk Schulze-Makuch; et al. (Dec 2011). "A Two-Tiered Approach to Assessing the Habitability of Exoplanets". Astrobiology. 11 (10): 1041–1052. Bibcode:2011AsBio..11.1041S. doi:10.1089/ast.2010.0592. PMID 22017274.

- ↑ Drake, Frank (1973). "Life on a Neutron Star". Astronomy. 1 (5): 5.

- ↑ Darling, David. "Neutron star, life on". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Bortman, Henry (29 September 2004). "Coming Soon: "Good" Jupiters". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ↑ Horner, Jonathan; Jones, Barrie (December 2010). "Jupiter – Friend or Foe? An answer". Astronomy and Geophysics. 51 (6): 16–22. Bibcode:2010A&G....51f..16H. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4004.2010.51616.x.

- ↑ Horner, Jonathan; Jones, B. W. (October 2008). "Jupiter – Friend or Foe? I: The Asteroids". International Journal of Astrobiology. 7 (3–4): 251–261. arXiv:0806.2795

. Bibcode:2008IJAsB...7..251H. doi:10.1017/S1473550408004187.

. Bibcode:2008IJAsB...7..251H. doi:10.1017/S1473550408004187. - ↑ Horner, Jonathan; Jones, B. W. (April 2009). "Jupiter – friend or foe? II: the Centaurs". International Journal of Astrobiology. 8 (2): 75–80. arXiv:0903.3305

. Bibcode:2009IJAsB...8...75H. doi:10.1017/S1473550408004357.

. Bibcode:2009IJAsB...8...75H. doi:10.1017/S1473550408004357. - ↑ Horner, Jonathan; Jones, B. W.; Chambers, J. (January 2010). "Jupiter – friend or foe? III: the Oort cloud comets". International Journal of Astrobiology. 9 (1): 1–10. arXiv:0911.4381

. Bibcode:2010IJAsB...9....1H. doi:10.1017/S1473550409990346.

. Bibcode:2010IJAsB...9....1H. doi:10.1017/S1473550409990346. - ↑ Lunine, Jonathan I. (30 January 2001). "The occurrence of Jovian planets and the habitability of planetary systems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (3): 809–814. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..809L. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.3.809. PMC 14664

. PMID 11158551.

. PMID 11158551. - ↑ Porter, Simon B.; Grundy, William M. (July 2011), "Post-capture Evolution of Potentially Habitable Exomoons", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 736 (1): L14, arXiv:1106.2800

, Bibcode:2011ApJ...736L..14P, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/736/1/L14

, Bibcode:2011ApJ...736L..14P, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/736/1/L14 - ↑ "The Living Worlds Hypothesis". Astrobiology Magazine. 22 September 2005. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

Bibliography

- Ward, Peter; Brownlee, Donald (2000). Rare Earth: Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe. Springer. ISBN 0-387-98701-0.

Further reading

- Cohen, Jack and Ian Stewart. Evolving the Alien: The Science of Extraterrestrial Life, Ebury Press, 2002. ISBN 0-09-187927-2

- Dole, Stephen H. (1965). Habitable Planets for Man (1st ed.). Rand Corporation. ISBN 0-444-00092-5.

- Fogg, Martyn J., ed. "Terraforming" (entire special issue) Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, April 1991

- Fogg, Martyn J. Terraforming: Engineering Planetary Environments, SAE International, 1995. ISBN 1-56091-609-5

- Gonzalez, Guillermo and Richards, Jay W. The Privileged Planet, Regnery, 2004. ISBN 0-89526-065-4

- Grinspoon, David. Lonely Planets: The Natural Philosophy of Alien Life, HarperCollins, 2004.

- Lovelock, James. Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. ISBN 0-19-286218-9

- Schmidt, Stanley and Robert Zubrin, eds. Islands in the Sky, Wiley, 1996. ISBN 0-471-13561-5

- Webb, Stephen If The Universe Is Teeming With Aliens ... Where Is Everybody? Fifty Solutions to the Fermi Paradox and the Problem of Extraterrestrial Life New York: January 2002 Springer-Verlag ISBN 978-0-387-95501-8

External links

- Planetary Sciences and Habitability Group, Spanish Research Council

- The Habitable Zone Gallery

- Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL/UPR Arecibo)

- The Habitable Exoplanets Catalog (PHL/UPR Arecibo)

- David Darling encyclopedia

- General interest astrobiology

- Sol Station