Five-year plans for the national economy of the Soviet Union

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Soviet Union |

|

Judiciary |

The five-year plans for the development of the national economy of the Soviet Union (USSR) (Russian: Пятиле́тние пла́ны разви́тия наро́дного хозя́йства СССР) were a series of nationwide centralized economic plans in the Soviet Union. The plans were developed by a state planning committee based on the theory of the productive forces that was part of the ideology of the Communist Party for development of the Soviet economy. Fulfilling the plan became the watchword of Soviet bureaucracy (see Overview of the Soviet economic planning process).

The same method of planning was also adopted by most other communist states, including the People's Republic of China. Nazi Germany emulated the practice in its four-year plan designed to bring Germany to war-readiness. Although the Republic of Indonesia is known for its anti-communist purge,[1] the Soeharto government also adopted the same method of planning. This series of five-year plans in Indonesia was termed REPELITA (Rencana Pembangunan Lima Tahun) I to VI from 1969 to 1998.[2][3][4]

Several five-year plans did not take up the full period of time assigned to them: some were successfully completed earlier than expected, while others failed and were abandoned. Altogether, there were thirteen five-year plans. The initial five-year plans were created to serve in the rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union and thus placed a major focus on heavy industry. The first one was accepted in 1928, for the period from 1929 to 1933, and completed one year early. The last five-year plan was for the period from 1991 to 1995 and was not completed, since the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991.

Background

| Part of a series on |

| Soviet economics |

|---|

|

Planning methods |

|

Joseph Stalin inherited and upheld the New Economic Policy (NEP) from Vladimir Lenin. In 1921, Lenin had persuaded the 10th Party Congress to approve the NEP as a replacement for the War Communism that had been set up during the Russian Civil War. In War Communism, the state had assumed control of all means of production, exchange and communication. All land had been declared nationalized by the Decree on Land, finalized in the 1922 Land Code, which also set collectivization as the long-term goal. Although the peasants had been allowed to work the land they held with the production surplus to their needs being bought by the state (on the state's terms), the peasants cut production; whereupon food was requisitioned. Money gradually came to be replaced by barter and a system of coupons.

The NEP took over from the failed attempts of War Communism. During this time, the state had controlled all large enterprises (i.e. factories, mines, railways) as well as enterprises of medium size, but small private enterprises, employing fewer than 20 people were allowed. The requisitioning of farm produce was replaced by a tax system (a fixed proportion of the crop), and the peasants were free to sell their surplus (at a state-regulated price) - although they were encouraged to join state farms (Sovkhozes, set up on land expropriated from nobles after the 1917 revolution), in which they worked for a fixed wage like workers in a factory. Money came back into use, with new bank notes being issued and backed by gold.

The NEP had been Lenin's response to a crisis. In 1920, industrial production had been 13% and agricultural production 20% of the 1913 figures. Between February 21 and March 17, 1921, the sailors in (Kronstadt) had mutinied. In addition, the Russian Civil War, which had been the main reason for the introduction of War Communism, had virtually been won; and so controls could be relaxed.

In the 1920s, there was a great debate between Bukharin, Tomsky and Rykov on the one hand, and Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev on the other. The former group considered that the NEP provided sufficient state control of the economy and sufficiently rapid development, while the latter argued in favour of more rapid development and greater state control, taking the view, among other things, that profits should be shared among all people, and not just among a privileged few. In 1925, at the 14th Party Congress, Stalin, as he usually did in the early days, stayed in the background but sided with the Bukharin group. However, later, in 1927, he changed sides, supporting those in favour of a new course, with greater state control.

Plans

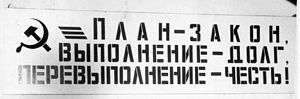

fulfillment – duty,

over-fulfillment – honor!"

Each five-year plan dealt with all aspects of development: capital goods (those used to produce other goods, like factories and machinery), consumer goods (e.g. chairs, carpets, and irons), agriculture, transportation, communications, health, education, and welfare. However, the emphasis varied from plan to plan, although generally the emphasis was on power (electricity), capital goods, and agriculture. There were base and optimum targets. Efforts were made, especially in the third plan, to move industry eastward to make it safer from attack during World War II. Because meeting the goals of the five-year plans had top priority as a measure of progress toward a communist utopia, official lying about productivity became part of the economic system. The attempt to turn an illiterate peasant society into an advanced industrial economy in a single decade brought intense suffering, but hardship was tolerated because, as one worker put it, Soviet workers believed in the need for "constant struggle, struggle, and struggle" to achieve a Communist society. These five-year plans outlined programs for huge increases in the output of industrial goods. Stalin warned that without an end to economic backwardness "the advanced countries...will crush us."[5]

First plan, 1928–1932

During this period, Stalin pursued the policy of "collectivization" in agriculture to facilitate the process of rapid industrialization; this involved the creation of collective farms in which peasants worked cooperatively on the same land with the same equipment. This was intended to improve the efficiency of agriculture and eliminate the "kulak" class of landowners, which was deemed hostile to the Soviet regime, while improving the position of poor peasants. The disruption and repression associated with collectivization is alleged to be the primary cause of the famine of 1932 by Ukrainian historians.

From 1928 to 1940, the number of Soviet workers in industry, construction, and transport grew from 4.6 million to 12.6 million and factory output soared.[6] Stalin's first five-year plan helped make the USSR a leading industrial nation.

During this period, the first purges were initiated targeting many people working for Gosplan. These included Vladimir Bazarov, the 1931 Menshevik Trial (centered around Vladimir Groman).

Stalin announced the start of the first Five-year plan for industrialization on October 1, of 1928 and it lasted until December 31 of 1932. Stalin described it as a new revolution from above.[7] When this plan began, the USSR was fifth in the industrial nation, with the great success of the first five-year plan the USSR moved up to second, with only the United States in first.[8]

This plan was achieved with great success in less time than had been predicted. When the plan was initially proposed it was instantly rejected as being too modest. The target goals were then increased by a reported fifty percent.[9] Much of the emphasis was placed on heavy industry. In fact, 86 percent of all industrial investments during this time went directly to heavy industry. Officially the first five-year plan for industry was fulfilled to the extent of 93.7 percent in just four years and three months.[8] The means of production in regards to heavy industry exceeded the quota, registering 103.4 percent. The light, or Consumer goods, industry reached up to 84.9 percent of its assigned quota.[8] There is some speculation regarding the legitimacy of these numbers as the nature of Soviet statistics are often misleading or exaggerated. Another issue was that quality was sacrificed in order to achieve quantity and because of this production results generated wildly varied items. This great industrial push created a lack in consumer goods and shortages in rationing.[8]

Propaganda used before, during and after the first five-year plan compared industry to battle. This was highly successful. They used terms such as “fronts,” “campaigns,” and “breakthroughs,” while at the same time workers were forced to be working harder than ever before and were organized into “shock troops,” and those who rebelled or failed to keep up with their work were treated as traitors as if they were in wartime.[8] The posters and flyers used to promote and advertise the plan were also reminiscent of wartime propaganda. A popular military metaphor emerged from the economic success of the first five-year plan, “There are no fortresses Bolsheviks cannot storm.” Stalin especially liked this.[8]

The first five-year plan was not just about economics. This plan was a revolution that intended to transform all aspects of society. The way of life for the majority of the people changed drastically during this revolutionary time. The plan was also referred to as the “Great Turn”.[8] Individual peasant farming gave way to a more efficient system of collective farming. Peasant property and entire villages were incorporated into the state economy which had its own market forces.[9]

There was however, a strong resistance to this at first. The peasants led an all-out attack to protect individual farming, however, Stalin did not see the peasants as a threat. Despite being the largest segment of the population they had no real strength, and thus could pose no serious threat to the state. By the time this was done, the collectivization plan resembled a very bloody military campaign against the peasant’s traditional lifestyle.[9] This great social transformation along with the incredible economic boom occurred at the same time that the entire Soviet system we know today, developed its definitive form in the decade of 1930.[8]

Many scholars believe that a few other important factors, such as foreign policy and internal security, went into the execution of the five-year plan. While ideology and economics were a major part, preparation for the upcoming war also affected all of the major parts of the five-year plan. The war effort really picked up in 1933 when Hitler came to power in Germany. The stress this caused on internal security and control in the five-year plan is difficult to document.[8]

Stalin was very creative when it came time to announcing the results of the first Five Year-Plan. Due to his complete unquestioned authority, he never had to cite or give a single statistic, fact or figure. While most of the figures were overstated, Stalin was able to announce truthfully that the plan had been achieved ahead of schedule, however the many investments made to the west were excluded. While many factories were built and industrial production did increase exponentially, they were not close to reaching their target numbers.[9]

While there was great success, there were also many problems with not just the plan itself, but how quickly it was completed. Its approach to industrialization was very inefficient and extreme amounts of resources were put into construction that, in many cases, was never completed. These resources were also put into equipment that was never used, or not even needed in the first place.[9] Many of the consumer goods produced during this time were of such low quality that they could never be used and were wasted.

A major event during the first Five Year-Plan was the Great Famine. The famine peaked during the winter of 1932-1933 claiming the lives of an estimated five to seven million people. Millions more permanently disabled.[9] The famine was the direct result of the industrialization and collectivization implemented by the first Five Year-Plan. Many of the peasants who were suffering from the famine began to sabotage the fulfillment's of their obligations to the state and would, as often as they could, stash away stores of food. Stalin was aware of this, however he placed the blame of the hostility onto the peasants, saying that they had declared war against the Soviet government.[9]

Second plan, 1933–1937

Because of the successes made by the first plan, Stalin did not hesitate with going ahead with the second five-year plan in 1932, although the official start-date for the plan was 1933. The second five-year plan gave heavy industry top priority, putting the Soviet Union not far behind Germany as one of the major steel-producing countries of the world. Further improvements were made in communications, especially railways, which became faster and more reliable. As was the case with the other five-year plans, the second was not as successful, failing to reach the recommended production levels in such areas as the coal and oil industries. The second plan employed incentives as well as punishments and the targets were eased as a reward for the first plan being finished ahead of schedule in only four years. With the introduction of childcare, mothers were encouraged to work to aid in the plan's success. By 1937 the tolkachi emerged occupying a key position mediating between the enterprises and the commissariat.[10]

Third plan, 1938–1941

The third five-year plan ran for only 3 years, up to 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union during the Second World War. As war approached, more resources were put into developing armaments, tanks and weapons, as well as constructing additional military factories east of the Ural mountains.

The first two years of the third five-year plan proved to be even more of a disappointment in terms of proclaimed production goals. Still, a reported 12% to 13% rate of annual industrial growth was attained in the Soviet Union during the 1930s. The plan had intended to focus on consumer goods. The Soviet Union mainly contributed resources to the development of weapons, and constructed additional military factories as needed. Stalin continued to implement additional Five Year Plans in the years following WWII, in an attempt keep his promise in 1945 to make the Soviet Union the leading industrial power by 1960. By 1952, industrial production was nearly double the 1941 level (“Five-Year Plans”). Stalin’s Five Year Plans helped transform the Soviet Union from an untrained society of peasants to an advanced industrial economy.

Fourth and fifth plans, 1945–1955

Stalin in 1945 promised that the USSR would be the leading industrial power by 1960.

The USSR at this stage had been devastated by the war. Officially, 98,000 collective farms had been ransacked and ruined, with the loss of 137,000 tractors, 49,000 combine harvesters, 7 million horses, 17 million cattle, 20 million pigs, 27 million sheep; 25% of all capital equipment had been destroyed in 35,000 plants and factories; 6 million buildings, including 40,000 hospitals, in 70,666 villages and 4,710 towns (40% urban housing) were destroyed, leaving 25 million homeless; about 40% of railway tracks had been destroyed; officially 7.5 million servicemen died, plus 6 million civilians, but perhaps 20 million in all died. In 1945, mining and metallurgy were at 40% of the 1940 levels, electric power was down to 52%, pig-iron 26% and steel 45%; food production was 60% of the 1940 level. After Poland, the USSR had been the hardest hit by the war. Reconstruction was impeded by a chronic labor shortage due to the enormous number of Soviet casualties in the war. Moreover, 1946 was the driest year since 1891, and the harvest was poor.

The USA and USSR were unable to agree on the terms of a US loan to aid reconstruction, and this was a contributing factor in the rapid escalation of the Cold War. However, the USSR did gain reparations from Germany, and made Eastern European countries make payments in return for the Soviets having liberated them from the Nazis. In 1949, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) was set up, linking the Eastern bloc countries economically. One-third of the fourth plan's capital expenditure was spent on Ukraine, which was important agriculturally and industrially, and which had been one of the areas most devastated by war.

Sixth plan, 1956–1960

Another plan to improve industry was carried out in 1956 by Nikita Khrushchev, following Stalin's death in 1953. Some of Khrushchev's policies included nationalization, the Virgin Lands Campaign, creation of a minimum wage alongside overall wage reform and the production of consumer goods which raised the living standards of the Soviet people in return.

Seventh plan, 1959–1965

Unlike other planning periods, it was a 7-year plan (Russian: семилетка, semiletka), approved by the 21st Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1959. It was the reconsideration of the 6th pyatiletka. This period was marked with a significant economic growth of the Soviet Union.

Eighth plan, 1966–1970

The eighth plan led to the amount of grain exported being doubled.

Ninth plan, 1971–1975

About 14.5 million tonnes of grain were imported by the USSR. Détente and improving relations between the Soviet Union and the United States allowed for more trade. The plan's focus was primarily on increasing the amount of consumer goods in the economy so as to improve Soviet standards of living. While largely failing at that objective[11] it managed to significantly improve Soviet computer technology.[12]

Tenth plan, 1976–1981

Leonid Brezhnev declared the slogan "Plan of quality and efficiency" for this period.

Eleventh plan, 1981–1985

During the eleventh five-year plan, the country imported some 42 million tons of grain annually, almost twice as much as during the tenth five-year plan and three times as much as during the ninth five-year plan (1971–1975). The bulk of this grain was sold by the West; in 1985, for example, 94 percent of Soviet grain imports were from the nonsocialist world, with the United States selling 14.1 million tons. However, total Soviet export to the West was always almost as high as import, for example, in 1984 total export to the West was 21.3 billion rubles, while total import was 19.6 billion rubles.

Twelfth plan, 1986–1990

The last, 12th plan started with the slogan of uskoreniye, the acceleration of economic development (quickly forgotten in favor of a more vague motto perestroika) ended among a profound economic crisis in virtually all areas of Soviet economy and drop in production.

The 1987 Law on State Enterprise and the follow-up decrees about khozraschyot and self-financing in various areas of the Soviet economy were aimed at the decentralization to overcome the problems of the planned economy.

Thirteenth plan, 1991

This plan, which would have run until 1995, only lasted about one year due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Information technology

State planning of the economy required processing large amounts of statistical data. The Soviet State had nationalized the Odhner arithmometer factory in Saint Petersburg after the revolution. The state began renting tabulating equipment later on. By 1929, it was a very large user of statistical machines, on the scale of the US or Germany. The State Bank had tabulating machines in 14 branches. Other users included the Central Statistical Bureau, the Soviet Commissariat of Finance, Soviet Commissariat of Inspection, Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Trade, the Grain Trust, Soviet Railways, Russian Ford, Russian Buick, the Karkov tractor factory, and the Tula Armament Works.[13] IBM also did a good deal of business with the Soviet State in the 1930s, including supplying punch cards to the Stalin Automobile Plant.[14][15]

Honors

The minor planet 2122 Pyatiletka discovered in 1971 by Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova is named in honor of Five-Year Plans of the USSR.[16]

See also

- Five-year plan (disambiguation) for similar plans in other countries

- Articles on individual Five-Year Plans for the Soviet Union:

- Soviet calendar

- Eastern Bloc economies

- Analysis of Soviet-type economic planning

- Tolkachi

References

- ↑ David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (2007) The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004156917 pp. 80–81.

- ↑ McDonald, Hamish (28 January 2008). "No End to Ambition". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ Robinson (2012), p. 178-203

- ↑ Sheridan, Greg (28 January 2008). "Farewell to Jakarta's Man of Steel". The Australian. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ↑ Hunt, Lynn (2010). The Making of the West, Volume II: Since 1500: Peoples And Cultures. MacMillan. p. 845.

- ↑ Lynn Hunt et al., The Making of the West, Peoples and Cultures: A Concise History (Since 1340), 3rd ed., vol. 2 (Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2010), 831–832.

- ↑ Sixsmith, Martin (2014). Russia A 1,000-Year Chronicle of the Wild East. New York: The Overlook Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Riasanovsky, Nicholas V (2011). A History of Russia. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Khlevniuk, Oleg V (2015). Stalin: New Biography of a Dictator. London: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Beissinger, Mark R. (1988). Scientific management, socialist discipline, and Soviet power. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674794907.

- ↑ L. Garthoff, Raymond (1994). Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. p. 613. ISBN 0-8157-3041-1.

- ↑ Beissinger, Mark R. (1988). Scientific Management, Socialist Discipline, and Soviet Power. Cambridege, Mass: Harvard University Press. p. 248. ISBN 0-674-79490-7.

- ↑ A Computer Perspective, by the office of Charles & Ray Eames, Edited by Glen Fleck, produced by Robert Staples, Introduction by I. Bernard Cohen, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1973, pgs 64, 96-97

- ↑ Before the computer by James W. Cortada, p142, who cites James Connolly, History of Computing in Europe, IBM World Trade Corporation 1967

- ↑ U.S. Ambassador Joseph E. Davies intercedes for IBM during Stalin's Great Purge, website by Hugo S. Cunningham, accessed 2010 9 16, which cites Joseph E. Davies, Mission to Moscow, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1941.

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 172. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.