Politics of the Southern United States

Politics of the Southern United States (or Southern politics) refers to the political landscape of the Southern United States. Due to the region's unique cultural and historic heritage, the American South has been prominently involved in numerous political issues faced by the United States as a whole, including States' rights, slavery, Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement. The region was a "Solid South" voting heavily for Democratic candidates for president, and for state and local offices, from the 1870s to the 1960s. Its Congressmen gained seniority and controlled many committees. In presidential politics the South moved into the Republican camp in 1968 and ever since, with exceptions when the Democrats nominated a Southerner. Since the 1990s control of state and much local politics has turned Republican in every state.

Definitions

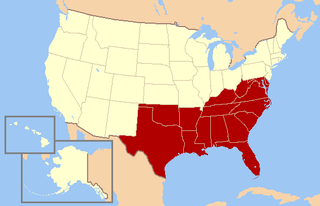

According to the United States Census Bureau the following states are considered part of the "south."

- Delaware

- Maryland

- Virginia

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Georgia

- Florida

- West Virginia

- Kentucky

- Tennessee

- Alabama

- Mississippi

- Arkansas

- Louisiana

- Oklahoma

- Texas

- Missouri

Other definitions can be more exclusive or more expansive. This represents a region of the United States with a diverse physical and cultural geography.. Missouri is not shown on many maps as a southern state and is considered a border state, yet many Missourians claim that Missouri is in the South.

After the Civil War

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 and 1868 placed most of the southern states under military rule, requiring Union Army governors to approve appointed officials and candidates for election. They enfranchised black citizens and required voters to recite an oath of allegiance to the US Constitution (including the 14th Amendment), which effectively barred passionate supporters of the rebel cause from voting, though enforcement was far from universal.[2] Democrats had regained power in most Southern states by the late 1870s, and began to pass laws to restrict black voting in a period they came to refer to as Redemption. From 1890–1908 states of the former Confederacy passed statutes and amendments to their state constitutions that effectively disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites in the South through devices such as poll taxes, and literacy tests.[3]

In the 1890s the white South split bitterly, with poor cotton farmers moving to the Populist movement. In coalition with the remaining Republicans the Populists briefly controlled Alabama and North Carolina. The local elites, based in courthouse rings and including the townspeople and the landowners fought back, and regained control of the Democratic party by 1898. However they had to reject the pro-gold, pro-Cleveland Bourbon Democrats and anchor the South in favor of inflationary free silver and march to the tune of William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1896, 1900 and 1908.[4]

Twentieth-century

During the 20th century, civil rights for blacks was a central issue of Southern politics. They were second class citizens with limited political rights before 1964.

1948: Dixiecrat revolt

Many Deep South Southern Democrats bolted the Democratic Convention over Harry's Truman's civil rights platform.[5] They met at Birmingham, Alabama, and formed yet another political party, which they named the "States' Rights" Democratic Party. More commonly known as the "Dixiecrats," the party's main goal was continuing the policy of racial segregation in the South and the Jim Crow laws that sustained it. South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, who had led the walkout, became the party's presidential nominee, and Mississippi Governor Fielding L. Wright received the vice-presidential nomination. Thurmond had a moderate position in South Carolina politics, but he now became the symbol of die-hard segregation.[6] The Dixiecrats had no chance of winning the election themselves, since they could not get on the ballot in enough states. Their strategy was to take enough Southern states from Truman to force the election into the House of Representatives, where they could then extract concessions from either Truman or Dewey on racial issues in exchange for their support. Even if Dewey won the election outright, the Dixiecrats hoped that their defection would show that the Democratic Party needed Southern support in order to win national elections, and that this fact would weaken proponents of the Civil Rights Movement among Northern and Western Democrats. However, the Dixiecrats were weakened when most Southern Democratic leaders (such as Governor Herman Talmadge of Georgia and "Boss" E. H. Crump of Tennessee) refused to support the party. Despite being an incumbent President, Truman was not placed on the ballot in Alabama. In the states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina, the party was able to be labeled as the main Democratic Party ticket on the local ballots on election night.[7] Outside of these four states, however, it was only listed as a third-party ticket.[8]

Civil Rights Movement

Between 1955 and 1968, a movement toward desegregation gained ground in the American South. While many individuals and organizations participated in the movement's early years, dating back to the start of the 20th century, in the 1950s-1960s Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a Baptist minister, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were highly influential in carrying out a strategy of non-violent protests and demonstrations. Black churches were prominent in organizing their congregations for moral leadership and protest. Protesters rallied against racial[9] laws, through such events as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Selma to Montgomery marches, the Birmingham campaign, the Greensboro sit-in of 1960, and the March on Washington in 1963.

Legal changes came in the mid-1960s when President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed through Congress over the vehement objects of Southern Democrats the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It effectively ended segregation. He also pushed through the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which enabled the federal government to guarantee black voting rights.[10] The leading black spokesman was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. continued his political activism, but his opposition to the Vietnam War brought him into conflict with President Johnson and the labor unions that had been powerful supporters.[11]

The South becomes Republican: 1964-2000

For nearly a century after Reconstruction, the white South strongly identified with the Democratic Party. The region was called the Solid South. Republicans controlled parts of the mountains districts and they competed for statewide office in the border states. Before 1948, southern Democrats believed that their party, with its respect for states' rights and appreciation of traditional southern values, was the defender of the southern way of life. Southern Democrats warned against aggressive designs on the part of Northern liberals and Republicans and civil rights activists whom they denounced as "outside agitators."

The adoption of the first civil rights plank by the 1948 convention and President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981, which provided for equal treatment and opportunity for African-American servicemen, opened a wedge between the northern and southern wings of the party.[12] By 1952, however, the brief Dixiecrat revolt was over and the Democratic Party named John Sparkman, a moderate Senator from Alabama, as their vice presidential candidate with the hope of building Party loyalty in the South.[13][14] By the late 1950s the national Democratic Party again began to embrace the Civil Rights Movement, and the old argument that Southern whites had to vote Democratic to protect segregation grew weaker. Modernization had brought factories, national businesses, and larger, more cosmopolitan cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, Charlotte, and Houston to the South, as well as millions of migrants from the North and more opportunities for higher education. They did not bring a heritage of racial segregation, and instead gave priority to modernization and economic growth.[15]

Integration and the Civil Rights Movement caused enormous controversy in the white South, with many attacking it as a violation of states' rights. School segregation was outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1954, but compliance was very slow in much of the region. The Civil Rights act of 1964 and The Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed by bipartisan majorities of northern congressmen. Only a small die-hard element resisted, led by Democratic governors Lester Maddox of Georgia, and especially George Wallace of Alabama. These populist governors appealed to a less-educated, blue-collar electorate that on economic grounds favored the Democratic Party, but opposed desegregation.

The passage of civil rights legislation meant that the Democratic Party could no longer pose as the champion of protection for southern segregation. That freed conservative white Southerners from the possibility of voting for Republican presidential candidates from 1964-80. They continued to vote heavily for Democrats in state and local offices.[16][17] Meanwhile, newly enfranchised black voters began supporting Democratic candidates at the 80-90-percent levels, producing Democratic leaders such as Julian Bond and John Lewis of Georgia, and Barbara Jordan of Texas. Just as Martin Luther King had promised, integration had brought about a new day in Southern politics.[18]

By the 1990s Republicans were starting to win elections at the statewide and local level throughout the South. By 2014, the region was heavily Republican at the local state and national level. A key element in the change was the transformation of evangelical white Protestants in the south from a largely nonpolitical approach to a heavily Republican commitment. Pew pollsters reported that, "In the late 1980s, white evangelicals in the South were still mostly wedded to the Democratic Party while evangelicals outside the South were more aligned with the GOP. But over the course of the next decade or so, the GOP made gains among white Southerners generally and evangelicals in particular, virtually eliminating this regional disparity."[19] Exit polls in the 2004 presidential election showed that Bush led Kerry by 70–30% among Southern whites, who comprised 71% of the voters. Kerry had a 90–9 lead among the 18% of Southern voters who were black. One-third of the Southern voters said they were white evangelicals; they voted for Bush by 80–20.[20]

After the 2016 election, every state legislature in the South was GOP-controlled.[21]

Twenty-first century

LGBT rights

Marriage

As of October 27, 2014, same-sex marriage was legal in the following Southern jurisdictions: Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Virginia, and West Virginia. Judges in Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, and Texas have struck down their state's same-sex marriage bans and those decisions are currently waiting on appeal.

In September 2004, Louisiana became the first state adopt a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage in the South. This was followed by Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Oklahoma in November 2004, Texas in 2005, Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia in 2006, Florida in 2008, and finally North Carolina in 2012. North Carolina became the 30th state to adopt a state constitutional ban of same-sex marriage. Federal courts have repeatedly struck down state laws and state constitutional bans, culminating in the Obergefell v. Hodges decision, decided on June 26, 2015, in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that same-sex marriage bans were unconstitutional.

Public opinion

A Washington Post/ABC News poll from February–March 2014 found 50% of Southerns support same-sex marriage, 42% oppose, and 8% have no opinion on the issue.[22]

Politics

.png)

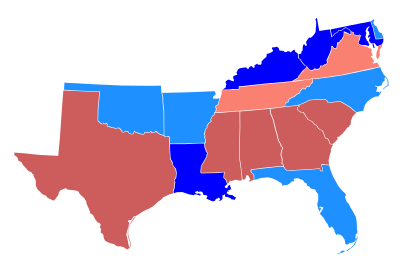

A map of the Southern United States, showing voter demographics 40-49% Republican

30-39% Republican

40-49% Democratic

50-59% Democratic |

While the general trend in the south has been increasing dominance of the Republican in the region, politics in the first quarter of the twenty-first century are just as contentious and competitive as any time in the region's history. States such as Florida, Virginia, and North Carolina have become swing states; all three of which voting for Barack Obama in the 2008 United States Presidential Election, as well as in 2012 for Florida and Virginia. Some election experts have speculated that Georgia could become a swing state in 2016 and Texas potentially joining them in the future. This can be explained by the fact that these states are experiencing a decline in their rural populations, an increase in their urban population, an influx of people from more liberal areas, as well as becoming more ethnically diverse.[23]

| Political views and affiliations | % living in the South | |

|---|---|---|

| Hard-Pressed Democrats[24] | 48 | |

| Disaffected[24] | 41 | |

| Bystander[24] | 40 | |

| Main Street Republicans[24] | 40 | |

| New Coalition Democrats[24] | 40 | |

| Staunch Conservative[24] | 38 | |

| Post-Modern[24] | 31 | |

| Libertarian[24] | 28 | |

| Solid Liberal[24] | 26 | |

See also

- Elections in the Southern United States

- Politics of the United States

- Blue Dog Democrats

- Boll weevil (politics)

- Conservative Democrat

- Southern Democrat

- Deep South

- Upland South

- History of the Southern United States

- History of the United States Republican Party

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- Political culture of the United States

- Southern Agrarians

- Southernization

- Southern strategy

References

- ↑ Regions and Divisions—2007 Economic Census". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ↑ "History Engine: The Second Reconstruction Act is passed". University of Virginia.

- ↑ Michael Perman, Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South (2009)

- ↑ C. Vann Woodward, The Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (1951)

- ↑ Harvard Sitkoff (November 1971). "Harry Truman and the Election of 1948: The Coming of Age of Civil Rights in American Politics". Journal of Southern History. 37: 597–616. JSTOR 2206548.

- ↑ Jack Bass, and Marilyn W. Thompson, Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond (2005).

- ↑ "Dixiecrats | New Georgia Encyclopedia". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. 2004-07-27. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ↑ Kari Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968 (2001)

- ↑

- ↑ Randall Woods, LBJ: Architect of American Ambition (2006)

- ↑ Taylor Branch, The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement (2013)

- ↑ Littlejohn, Jeffrey L., and Charles H. Ford. "Truman and Civil Rights." in Daniel S. Margolies, ed. A Companion to Harry S. Truman (2012) p 287.

- ↑ https://partners.nytimes.com/library/politics/camp/520727convention-dem-ra.html

- ↑ http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1441

- ↑ Byron E. Shafer, The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (2006) ch 6

- ↑ Shafer, The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (2006) ch 6

- ↑ David Lublin, The Republican South: Democratization and Partisan Change (Princeton University Press, 2004)

- ↑ Lawson, Steven F. (1991). "Freedom then, freedom now: The historiography of the civil rights movement". American Historical Review. 96: 456–471. JSTOR 2163219.

- ↑ "Religion and the Presidential Vote | Pew Research Center". People-press.org. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ↑ "Exit Polls". CNN. 2004-11-02. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ↑ Loftus, Tom (November 9, 2016). "GOP takes Ky House in historic shift". courier-journal.com. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Overall, do you support or oppose allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ↑ "Sweet Georgia Blue: Why Democrats Should Be Bullish on the Peach State". Huffington Post. 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Beyond Red vs. Blue : Political Typology" (PDF). People-press.org. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

Bibliography

- Bartley, Numan V. The New South, 1945-1980 (1995), broad survey

- Billington, Monroe Lee. The Political South in the 20th Century (Scribner, 1975). ISBN 0-684-13983-9.

- Black, Earl, and Merle Black. Politics and Society in the South (1989) excerpt and text search

- Bullock III, Charles S. and Mark J. Rozell, eds. The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics (2007) state-by-state coverage excerpt and text search

- Cunningham, Sean P. Cowboy Conservatism: Texas and the Rise of the Modern Right. (2010).

- Grantham. Dewey. The Democratic South (1965)

- Guillory, Ferrel, "The South in Red and Purple: Southernized Republicans, Diverse Democrats," Southern Cultures, 18 (Fall 2012), 6–24.

- Key, V. O. and Alexander Heard. Southern Politics in State and Nation (1949), a famous classic

- Perman, Michael. Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South (2009)

- Shafer, Byron E., and Richard Johnston. The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (2009) excerpt and text search

- Steed, Robert P. and Laurence W. Moreland, eds. Writing Southern Politics: Contemporary Interpretations and Future Directions (2006); historiography & scholarly essays excerpts & text search

- Tindall, George Brown. The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945 (1967), influential survey

- Twyman, Robert W. and David C. Roller, ed. Encyclopedia of Southern History (LSU Press, 1979) ISBN 0-8071-0575-9.

- Woodard, J. David. The New Southern Politics (2006) 445pp

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (1951), a famous classic