Muisca art

|

| Muisca |

|---|

| Topics |

| Geography |

| The Salt People |

| Main neighbours |

| History & timeline |

.jpg)

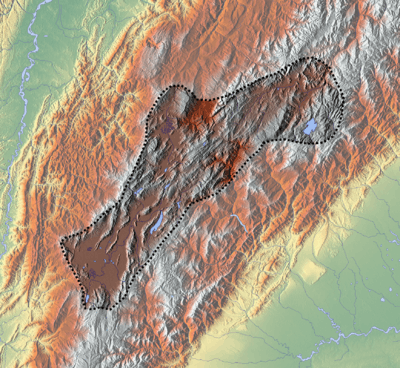

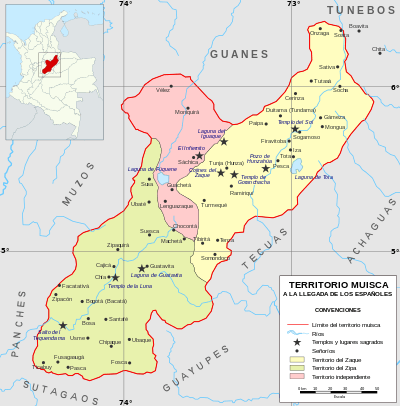

This article describes the art produced by the Muisca. The Muisca established one of the four grand civilisations of the pre-Columbian Americas on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in present-day central Colombia. Their various forms of art have been described in detail and include pottery, textiles, body art, hieroglyphs and rock art. While their architecture was modest compared to the Inca, Aztec and Maya civilisations, the Muisca are best known for their skilled goldworking. The Museo del Oro in the Colombian capital Bogotá houses the biggest collection of golden objects in the world, from various Colombian cultures including the Muisca.

The first art in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes goes back several millennia. Although this predates the Muisca civilisation, whose onset is commonly set at 800 AD, nevertheless, some of these styles persevered through the ages.

During the preceramic era, the people of the highlands produced petrographs and petroglyphs representing their deities, the abundant flora and fauna of the area, abstract motives and anthropomorphic or anthropo-zoomorphic elements. The self-sufficient sedentary agricultural society developed into a culture based on ceramics and the extraction of salt in the Herrera Period, usually defined as 800 BC to 800 AD. During this time, the oldest existing form of constructed art was erected; the archaeoastronomical site called El Infiernito ("The Little Hell") by the catholic Spanish conquistadors. The Herrera Period also marked the widespread use of pottery and textiles and the start of what would become the main motive for the Spanish conquest; the skilled fine goldworking. The golden age of Muisca metallurgy is represented in the Muisca raft, considered the masterpiece of this technology and depicts the initiation ritual of the new zipa of Bacatá, the southern part of the Muisca Confederation. This ceremony, performed by xeques (priests) and caciques wearing feathered golden crowns and accompanied by music and dance, took place on a raft in Lake Guatavita, in the northern part of the flat Bogotá savanna. Accounts of such ceremonies created the legend of El Dorado among the Spanish, leading them on a decade-long quest for this mythical place.

The rich art elaborated by the Muisca has inspired modern artists and designers in their creativity. Muisca motives are represented as murals, in clothing and as objects found all over the former Muisca territories as well as in animated clips and video games. The art of the indigenous inhabitants of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense is well studied by many different researchers who published their work right from the beginning of colonial times. The conquistador who made first contact with the Muisca, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, wrote in his memoires about a skilled and well-organised civilisation of traders and farmers. Friar Pedro Simón described the relation between art and the religion and later contributions in the analysis of the various artforms have been made by Alexander von Humboldt, Joaquín Acosta and Liborio Zerda in the 19th century, Miguel Triana, Eliécer Silva Celis and Sylvia M. Broadbent in the 20th century and modern research is dominated by the work of Carl Henrik Langebaek Rueda, Javier Ocampo López and many others.

Background

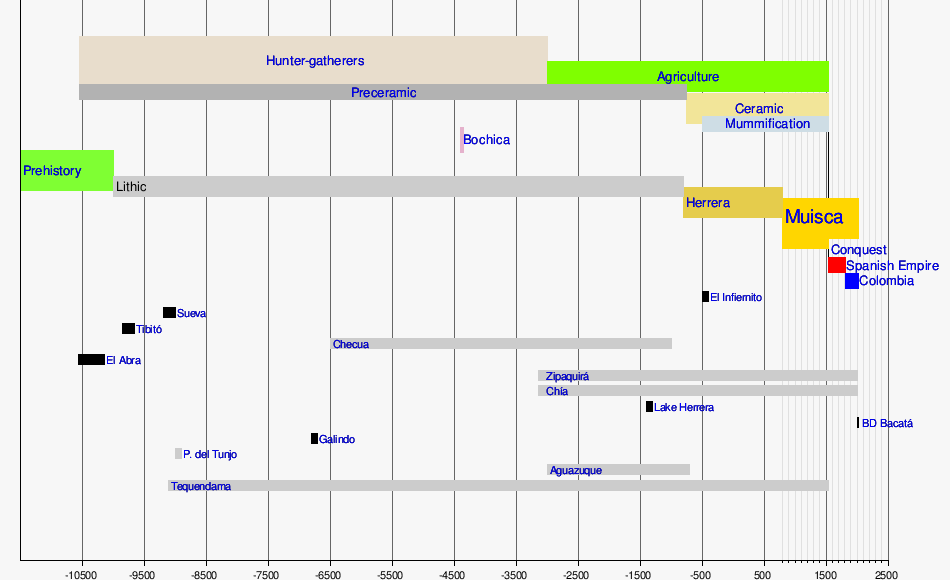

The central highlands of the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, called Altiplano Cundiboyacense was inhabited by indigenous groups from 12,500 BP, as evidenced from archaeological finds at rock shelter El Abra, presently part of Zipaquirá. The first human occupation consisted of hunter-gatherers who foraged in the valleys and mountains of the Andean high plateau. Settlement in the early millennia of this Andean preceramic age was mainly restricted to caves and rock shelters, such as Tequendama in present-day Soacha, Piedras del Tunjo in Facatativá and Checua that currently is part of the municipality Nemocón. Around 3000 BC, the inhabitants of the Andean plains started to live in open space areas and constructed primitive circular houses where they elaborated the stone tools used for hunting, fishing, food preparation and primitive art, mostly rock art. The type site for this transition is the archaeological site Aguazuque, in the northwest of Soacha, close to Bogotá.

Abundant evidence for the domestication of guinea pigs has been found at Tequendama and Aguazuque where the small rodents formed part of the diet of the people, who consumed mainly white-tailed deer, hunted on the plains surrounding the various lakes and rivers. The diet was greatly expanded when early agriculture was introduced, possibly influenced by migrations from the south; present-day Peru. The main cultivated product was maize in various forms and colours, while tubers formed a significant other part of the food source. The fertile soils of especially the Bogotá savanna proved advantageous for the development of this agriculture, still evidenced today by the widespread farmfields outside the Colombian capital.

| Timeline of inhabitation of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia | |

|

.png) |

Pre-Muisca art

The first forms of art recognised on the Altiplano are petrographs and petroglyphs in various locations on the Altiplano, mainly at the rock shelters of the Bogotá savanna. El Abra, Piedras del Tunjo and Tequendama are among the oldest sites where rock art has been discovered.[1] The Herrera Period, commonly defined from 800 BC to 800 AD, was the age of the first ceramics. The oldest Herrera pottery has been discovered in Tocarema and dates to 800 BC.[2] Herrera art is also represented by the archaeoastronomical site, called El Infiernito by the Spanish. On a field outside Villa de Leyva, menhirs in the shape of aligned phalluses were erected. This site, the oldest remaining of constructed art, dated at 500 BC, formed an important place for religious rituals and festivities where great quantities of the alcoholic drink chicha was consumed. The evidence for festivities at this site are from a later date, already in the Muisca Period.[3]

The goldworking in the northern parts of South America, mainly in present-day Colombia, is thought to originate from regions more to the south; the north of Peru and Ecuador, during a large timespan from 1600 to 1000 BC.. The development of different goldworking cultures in southern Colombia happened around 500 BC.[4] The late Herrera Period showed the first evidences of goldworking on the Altiplano. Golden artefacts have been found in Tunja and Cómbita in Boyacá and Guatavita in Cundinamarca with estimated ages ranging from 250 to 400 AD.[5]

Muisca art

The Muisca period is commonly set commencing from 800 AD and lasting until the Spanish conquest of the Muisca in 1537, although regional variations of the start dates are noted. The Early Muisca Period, roughly defined from 800 to 1000 AD, showed an increase in long-distance trade with the Caribbean coastal indigenous populations, mummification and the introduction of goldworking.[6] The transition between Early Muisca and Late Muisca is defined by a more complex society, interregional trade of pottery, population growth and settlements of larger sizes closer to the agricultural lands. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived on the Altiplano, they described a concentration of settlements on the flatlands of the Bogotá savanna.[6]

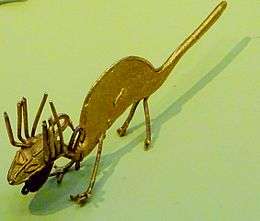

Zoomorphic figurines

As the Tairona of the Colombian Caribbean coast, the Muisca made the zoomorphic figurines based on the fauna with their habitat of the area. Main animals used for their figures were the frog and serpents. The serpents were made in zig-zag shapes with eyes on top of the head. Many serpentiform objects have the typical forked tongue of the snake represented as well as the fawns clearly added. Some of the snakes have beards, moustaches or even a human head.[7] Researcher Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff theorised in his book Orfebrería y chamanismo in 1988 that the basis for the beards and moustaches may have been the abundant fish present on the Altiplano and essential part of the diet of the Muisca and their ancestors, as evidenced in Aguazuque; Eremophilus mutisii.[8][9][10]

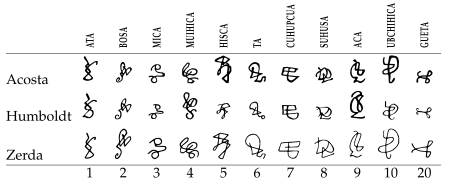

Frogs (iesua, meaning "food from the Sun") and toads were important animals in the concept of nature and the relation with the spiritual world for the Muisca.[11] They represented the start of the rainy season, which is illustrated in the use in the Muisca calendar; the symbols for the first (ata), ninth (aca) and holy twentieth (gueta) month of the years are derived from toads. The common year of the complex lunisolar calendar consisted of twenty months.[12] The frogs are shown in many different settings and forms of art; painted on ceramics, in the hieroglyphs of the rock art and as figurines. In many cases they are shown in combination with everyday activities and were used to represent humans, mostly women.[13]

Goldworking

The Muisca were famous for their goldworking. Although in the Muisca Confederation gold deposits were not abundant, the people obtained a lot of gold through trading, mainly in La Tora (called Barrancabermeja today) and other locations at the Magdalena River.[14] The earliest radiocarbon dates of goldworking of the Muisca are derived from carbon traces in the cores of golden noserings and provided ages of between 600 and 800 AD. The oldest evidences for Muisca goldworking were found in Guatavita, Fusagasugá and El Peñon, all in present-day Cundinamarca. The goldwork bears similarity but is not identicial to the metallurgy of the Quimbaya of the Cauca and Magdalena Valleys.[15]

Based on the stylistic variablity and metallurgic technology analysed in Muisca goldworking, three processes have been concluded;

- the Herrera people elaborated golden and copper objects such as crowns, and other offering figures from alluvial resources using the first molds and hammers and possibly matrixes.

- Around 400 AD, the metallurgy became more advanced, using the tumbaga alloy and an increase in the production of offering figures is noted.

- The last phase of skilled goldworking is characterised by more detailed goldworking using gold from trade with other indigenous groups.[16]

With the indigenous groups closer to the Caribbean Coast, the people traded highly valuable sea snails. Ironically, the sea snails were worth more than the price of gold to the Muisca, due to the distance from their location far inland high in the Andes. The skilled goldworking of the Muisca formed the basis for the legend of El Dorado that became widespread among the Spanish conquistadors; this eventually drew them into the heart of Colombia -- an ill-fated expedition that took almost a year and cost the lives of about 80% of their men.[17][18]

Tunjos

Tunjos (from Muysccubun: tunxo)[19] are small votive offering figures produced in great quantities by the Muisca. They are found in various places on the Altiplano, mainly in lakes and rivers, and are the most common object housed in museum collections outside Colombia.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32] The word tunjo was used first in the literature about the Muisca in 1854, by scholar Ezequiel Uricoechea.[33] The figurines are mostly anthropomorphic with other examples being zoomorphic. The tunjos were mostly elaborated using tumbaga; an alloy of gold, copper and silver, some with traces of lead or iron.[34] The majority of ceramic or stone tunjos has been described from Mongua, close to Sogamoso.[35] The tunjos served three purposes; as decoration of temples and shrines, for offering rituals in the sacred lakes and rivers in the Muisca religion, and as pieces in funerary practices; to accompany the dead to the afterlife.[34] Ceramic human Tunjos were kept in the houses (bohíos) of the Muisca, together with emeralds.[36]

The precious metals silver and gold were not common in the Eastern Ranges, while copper was mined in Gachantivá, Moniquirá and in the mountains to the south of the Bogotá savanna at Sumapaz. The process of elaborating the fine filigree figures took place by creating a mold of obsidian, shale or clay, filling the open space with bee wax, obtained through trade with the neighbouring indigenous peoples from the Llanos Orientales to the east of the Altiplano; the Achagua, Tegua and Guayupe. The bee wax occupied the voids of the mold and the mold was heated by fires. The bee wax would melt, leaving an open space where the tumbaga or sometimes gold was poured into, a process called lost-wax casting.[34] Using this method, modern tunjos are still fabricated in the centre of Bogotá.[37]

Between 1577 and 1583, various colonial writers have reported in their chronicles the use of tunjos for offering pieces. The descriptions from the early colonial period of the New Kingdom of Granada have been collected first by Vicenta Cortés Alonso in 1958 and later by Ulises Rojas in 1965. The reports of the late 16th century show that the religious practices of the Muisca were still alive, despite the intensive catholic conversion policies.[38] Caciques of Tuta, Toca, Duitama, Iguaque, Ramiriquí, Chitagoto, Onzaga, Tunja and Cucunubá participated in these rituals.[39] The religious leader of Sogamoso was still the most important in these days.[40]

-

Collection of tunjos

-

Tunjo formed by parents with children

-

Anthropomorphic tunjo in the Muisca exhibition of the Museo del Oro

-

Tunjo decorated with earrings

-

Tunjo of a mother with baby in her arms

-

Zoomorphic tunjo in the Museo del Oro

-

Mold used for the elaboration of tunjos

Muisca raft

The Muisca raft is the masterpiece of the Muisca goldworking and has become illustrative for the fine techniques used. The 19.1 centimetres (7.5 in) by 10 centimetres (3.9 in) object was found in 1969 in a ceramic pot hidden in a cave in the municipality of Pasca, in the southwest of the Bogotá savanna and has become the centerpiece in the Museo del Oro in Bogotá.[41][42] The raft is interpreted as picturing the initiation ritual of the new zipa in the sacred Lake Guatavita, where the new ruler would cover himself in gold dust and jump from a small boat in the waters of the 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) post-glacial lake to honour the gods. This ceremony was accompanied by priests (Muysccubun: xeque) and formed the basis for the El Dorado legend that drew the Spanish conquistadors towards the high Andes. The raft has been constructed using the lost-wax casting method and is made of tumbaga of around 80 % gold, 12 % silver and 8 % copper.[43] It contains 229 grams of gold.

The Muisca raft is also featured in the coat of arms of two municipalities of Cundinamarca; Sesquilé, where Lake Guatavita is located, and Pasca, where the raft was found.[44][45]

.svg.png)

Jewelry

The Muisca society was in essence egalitarian with slight differences in terms of use of jewelry. The guecha warriors, priests and caciques were allowed to wear multiple types of jewelry, while the common people used less jewels. Golden or tumbaga jewelry existed of diadems, nose pieces, breast plates, earrings, pendants, tiaras, bracelets and masks.[36]

-

Pectoral of tumbaga, Museo del Oro

-

Golden Muisca mask, Museo del Oro

-

Golden Muisca nariguera (nose piece) displayed in the Museo del Oro

-

Diadems of gold were common head pieces for the Muisca

-

.jpg)

The Muisca wore golden bracelets

-

The use of nose rings, earrings and crowns and diadems by the people is represented in many golden figures

-

The guecha warriors were allowed to wear feathered crowns and golden jewelry

Architecture

While the other three grand pre-Columbian civilisations -- the Maya, Aztec and Inca -- are known for their grand architecture in the form of pyramids, stelae, stone cities and temples, the modest Muisca architecture has left very little traces in the present.[46] The houses (called bohíos or malokas) and temples of the people, where spiritual gatherings took place honouring the gods and sacrificing tunjos, emeralds and children, were made of degradable materials such as wood, clay and reed. The circular structures were built on top of slightly elevated platforms to prevent them from flooding on the frequently inundated plains; small settlements of ten to one hundred houses were surrounded by wooden poles forming an enclosure, called ca in Muysccubun.[47][48] Two or more gates gave entrance to the villages.[49] The houses and temples themselves were built around a central pole of wood attached to the roof; the temples were constructed using the wood of Guaiacum officinale tree , giving high quality construction.[50] The floors of the open spaced houses were covered with straw or, for the caciques, with ceramic floors.[51][52] Cloths were attached to the roof and painted with red and black colours. The houses and sacred places were adorned with tunjos and emeralds, and in some cases with the remains of human sacrifices.[53]

Roads

The roads the Muisca merchants and xeques used to traverse the Altiplano and access surrounding areas, were dug in the top soil without pavement, making them hard to recognise in the archaeological record. The roads leading to the religious sites, such as Lake Tota, were marked with stones surrounding the pathway, which are still visible today.[54] Cable bridges of vines and bamboo connected the banks of the many rivers of the Andes. The roads crossing the mountains of the Eastern Ranges were narrow, which created a problem for the Spanish conquistadors who used horses to travel long distances.[55]

Remaining antiquities

A few structures built by the Muisca still exist today; the Cojines del Zaque ("cushions of the zaque") in Tunja are two round stones with inclined upper parts used for religious ceremonies. Of the Goranchacha Temple, a circle of pillars remained, located on the terrains of the UPTC, also in Tunja. The holiest temple of the Muisca, the Sun Temple in sacred City of the Sun Sugamuxi had been destroyed by fire when the Spanish conquerors looted the shrine and has been rebuilt based on archaeological research by Eliécer Silva Celis. The temple is part of the Archaeology Museum of the city in Boyacá.[56]

-

The Sun Temple in Sogamoso (Sugamuxi) was the most important temple for the Muisca

-

The Cojines del Zaque in Tunja (Hunza)

-

Muisca bohíos are depicted in the upper right of the seal of Sopó

Mummies

Mummification was a tradition that many other pre-Columbian civilisations practiced. On the Altiplano, the habit of conserving the dead started in the Herrera Period, around the 5th century AD.[57] The Muisca continued this culture and prepared their deceased beloved members of the society by putting the bodies above fires. The heat would dry the body and the phenol conserve the organs and protect them from decomposition, a process that took up to eight hours.[58] After drying, the bodies were wrapped in cotton cloths and placed in caves, buried, or in some cases placed on elevated platforms inside temples, such as the Sun Temple.[59][60][61] The position of the mummies was with their arms folded across the chest and the hands around the chin, while the legs were placed over the abdomen. During the preparation of the mummies, the Muisca played music and sang songs honouring their dead. The habit of mummification continued well into the colonial period; the youngest mummies found date from the second half of the 18th century.[59][62][63][64]

To prepare the dead for the afterlife, the mummies were surrounded with ceramic pots containing food, tunjos and cotton bags and mantles.[57] The guecha warriors were richly venerated with golden arms, crowns, emeralds and cotton.[65] When the caciques and zaque and zipa died, their mummified bodies were placed in mausoleums and surrounded with golden objects. The highest regarded members of society were accompanied by their many wives, by slaves and their children. The mummy of a baby described from a cave in Gámeza, Boyacá, had a teether around the neck.[66] Other mummies of children were richly decorated with gold and placed in caves, as was the case with a young girl described by Liborio Zerda.[58]

The art of mummification was also practiced by other Chibcha-speaking groups in the Eastern Ranges; the Guane mummies are well studied, and also the U'wa and farther north the Chitarero of the department of Norte de Santander mummified their dead.[67][68] The Carib-speaking Muzo buried their mummies with the head towards the west, while the Zenú and Panche, like the Muisca commonly oriented the faces of their mummies to the east. Some of the Muisca mummies were directed towards the south.[69]

When the guecha warriors fought battles with neighbouring groups, most notably the Panche, and also against the Spanish conquistadors, they carried the mummies of their ancestors on their backs, to impress the enemy and receive fortune in battle.[59][65][70][71][72]

-

Cotton Muisca textile bag, accompanying the mummy shown on the right

-

.jpg)

Small ceramic pots surrounded the mummies and contained food for the afterlife

-

Maize was the main ingredient of the Muisca diet and placed with the mummies

Music and dance

The Muisca played music, sang and danced mainly as part of religious, burial and initiation rituals, with harvests and sowing and after the victory in battles.[73][74] Also during the construction of their houses, the Muisca performed music and dances. The early Spanish chronicles noted that the music and singing was monotonous and sad.[75] As musical instruments they used drums, flutes made of shells or ceramics, trumpets of gold, zampoñas and ocarinas.[76] At the rituals, the people would be dressed in feathers, animal skins (mainly jaguar) and decorated their bodies with paint. At the dances the women and men held hands and both the commoners and the higher social classes participated in these activities. The main deities associated with the dances were Huitaca and Nencatacoa.[77][78][79]

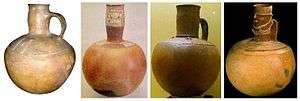

Ceramics

The use of ceramics on the Altiplano started in the Herrera Period, with the oldest evidences of ceramic use dated at 3000 BP. The many different clays of the rivers and lakes of the valleys on the high plateau made a variety of ceramic types possible.

The Muisca constructed ceramic pottery for cooking, the extraction of salt from brines, as decorative ritual pieces and for the consumption of their alcoholic beverage; chicha. Large ceramic jars were found around the sacred archaeoastronomical site of El Infiernito, used for massive rituals where the people celebrated their festivities drinking chicha.[80] Also musical instruments such as ocarinas were made of ceramics. The ceramic pots and sculptures were painted with zoomorphic figures that were common in the Muisca territory; frogs, armadillos, snakes and lizards. Main ceramic production centres were located close to the abundance of clays, in Tocancipá, Gachancipá, Cogua, Guatavita, Guasca and Ráquira.[36]

-

Ceramic bowl and tunjos, Museo del Oro, Bogotá

-

Ceramic mask of the Muisca, Museo Nacional, Bogotá

-

.jpg)

Quite some Muisca ceramics is characterised by the typical shapes of the eyes and mouth

Textiles

The Muisca, as the indigenous groups in the west of Colombia, developed a variety of textiles from fique or cotton.[81][82] Cords were made ofo fique or human hair.[82] The people of the cold climate Altiplano did not have a major cotton production, yet traded most of their cotton with their neighbours; the Muzo in the west, Panche in the southwest, Guane in the northwest, and the Guayupe in the east.[82] From the raw cotton, the Muisca women made fine cotton mantles that were traded on the many markets in the Muisca territory.[83]

The mantles of the Muisca were decorated with various colours. The colours were obtained from seeds; the seed of the avocado for green, flowers; saffron for orange and indigo weed for blue, fruits, crust and roots of plants, from animals as the cochineal insect producing purple colours, and minerals as the blue and green clays of Siachoque, the coloured earth of Suta and the yellow sediments of Soracá.[84] Also curuba, the flowers of the potato plant (Solanum andigenum) and other colouring materials (Rumex obtusifolia, Bixa orellana, Arrabidaea chica and more) were used.[85] The colours were applied using pencils, applying coloured threads or using stamps.[86] The textiles were produced using various techniques, similar to the Aymara of southern South America and the Mesoamerican cultures.[87] Small textiles functioned as money, just like the tejuelos of gold or salt was used.[88]

The culture of mantle-making in the Muisca mythology is said to have been taught by Bochica, who trained the people in the use of spindles.[89] Nencatacoa protected the weavers and painters of the mantles.[90]

-

_04_ies.jpg)

Cochineal lice were used to obtain purple colours

-

The ruana was a special kind of Muisca mantle, similar to the poncho

note: this is a modern version -

As the Guane, in this example, the Muisca made long mantles to protect them from the cold climate

-

The Muisca used spindle whorls to keep the mantles in place

Hieroglyphs

A script for text was not used by the Muisca, but the numerals were written with hieroglyphs. They have been analysed by various authors, such as Joaquín Acosta, Alexander von Humboldt and Liborio Zerda, and appear as rock art and on textiles. The frog is the most important and is represented in the numbers from one (ata) to twenty (gueta) five times, because the Muisca didn't have hieroglpyhs for the numbers 11 to 19, so used the numerals one to nine again in combination with ten; fifteen was thus ten-and-five; qhicħâ hɣcſcâ.[91][92]

Body art

Tattoos were common for the Muisca and an expression of their identity.[93][94] The people used Bixa orellana to paint their bodies, just like the Arawak, Carib and Tupi.[95]

Rock art

Many examples of rock art by the Muisca have been discovered on the Altiplano. The first rock art has been discovered by conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada during the Spanish conquest of the Muisca.[96] The rock art consists of petroglyphs (carvings) and petrographs (drawings). The petrographs were made using the index finger.[97] Pioneer in the study of the rock art has been Miguel Triana.[98] Later contributions have been done by Diego Martínez, Eliécer Silva Celis and others.[99] It is theorised that the rock art has been made under the influence of ayahuasca (yahé).[100]

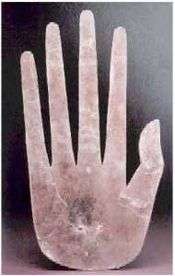

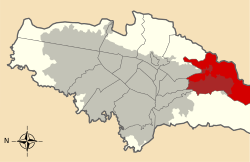

The rock art of Soacha-Sibaté, in the southwest of the Bogotá savanna, has been studied in detail between 1970 and 2006, after initial studies by Triana.[96][101] In these petrographs certain motives have been described; triangular heads are pictographs of human figures where the heads are painted in a triangular shape. They are applied using red colours and demonstrate various sizes. Similar motives are noted in Mongua, Tenjo and Tibacuy.[102] In most cases of the rock art on the Altiplano, the body extremities, such as hands, are shown in simple shapes. In some cases however, the hands are elaborated with much more detail using spirals, concentric circles and more strokes, identified as complex hands. Apart from Sibaté, these shapes are encountered also in Saboyá and Tibaná in Boyacá.[103] A third class of petrographs has been named radial representations. This motive shows the main figures with concentric square or circular lines drawn around them.[104] The concentric circular drawings have been interpreted as representing the main deities of the Muisca religion; Chía (the Moon) and Sué, her husband the Sun.[105] Rhomboidal motives are found in Sibaté, but their exact purpose has not yet been concluded.[106] Both in Soacha and in Sibaté a fifth type of petrographs has been identified; winged figures. These motives resemble the birds that are described in tunjos and ceramics of the Altiplano.[106]

The same scholar has performed detailed analysis of the rock art in Facatativá; the Piedras del Tunjo Archaeological Park. The many petrographs in this location are painted using red, yellow, ochre, blue, black and white colours.[107][108][109][110] The motives show a possible tobacco plant, commonly used by the Muisca, zig-zag patterns, anthropomorphic figures, concentric lines similar to those in Soacha and Sáchica, zoomorphic motives and anthropo-zoomorphic composites in the shape of frogs.[109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116]

Research in the 1960s by Eliécer Silva Celis on the rock art of Sáchica showed phytomorphic designs, masked human figures, singular and concentric rings, triangulated heads, and faces where the eyes and noses were drawn, but the mouths absent.[117] The majority of the petrographs found here are abstract figures.[118] The colours red, black and white dominate the rock paintings in Sáchica. The black has been analysed also at El Infiernito and is though to refer to a pre-Muisca origin.[119] Radial structures drawn on the heads of the anthropomorphic petrographs are interpreted as feathers.[120] Feathers were precious objects for the Muisca and used by the xeques and caciques during the El Dorado ritual in Lake Guatavita.[121]

Hand imprints, similar to the famous Cueva de las Manos in Argentina, yet less pronounced and in quantity, have been discovered on rock faces in Soacha and Motavita.[122]

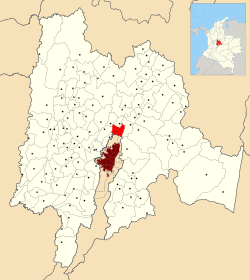

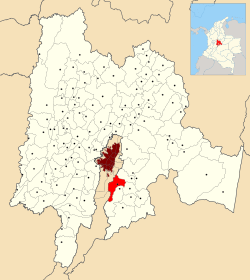

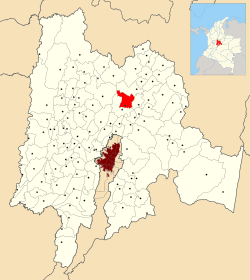

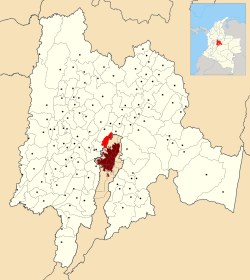

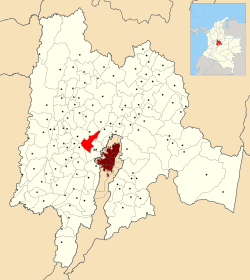

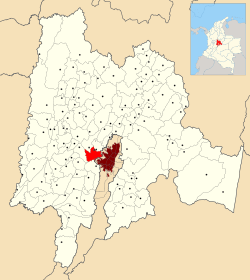

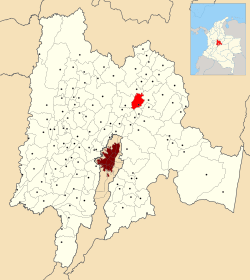

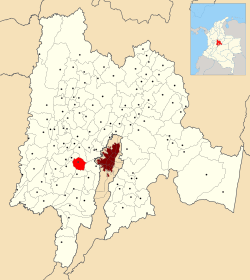

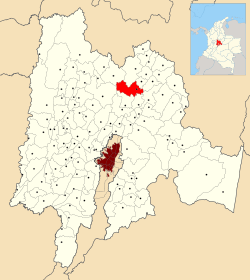

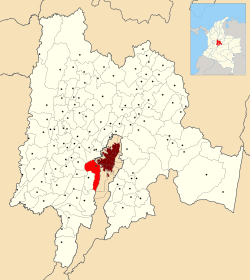

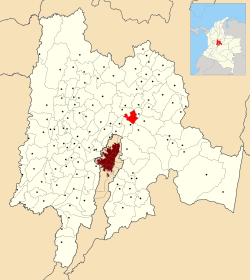

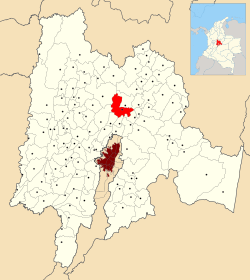

Muisca rock art on the Altiplano

As of 2006, 3487 locations of rock art had been discovered in Cundinamarca alone, of which 301 on the Bogotá savanna.[123] Other locations have been found over the years.[1][123] [124][125][126] The rock art of the Archaeological Park of Facatativá is heavily vandalised.[127] Plans for the preservation of the unique cultural heritage have been formulated since the mid 2000s.[128] The petrographs of Soacha are endangered by the mining activities in the fastly growing suburb of Bogotá, as is happening with other mining districts; Chía, Sibaté, Tunja, Sáchica and others.[129]

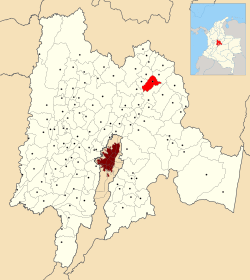

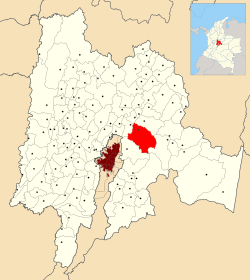

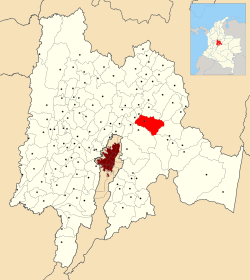

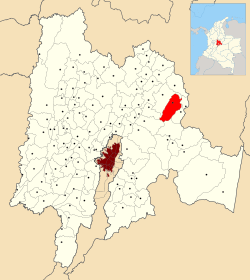

| Settlement | Department | Altitude (m) urban centre |

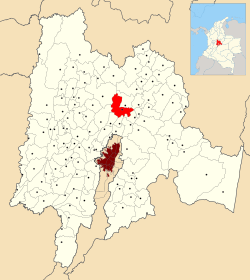

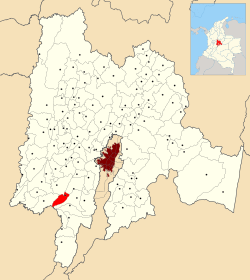

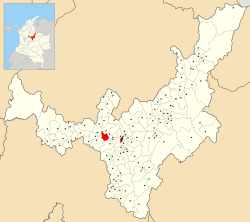

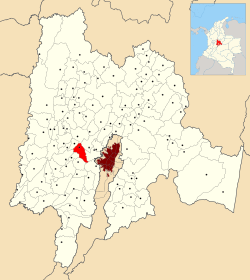

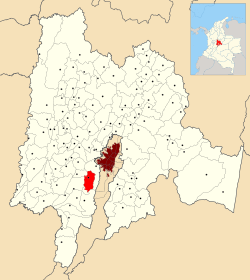

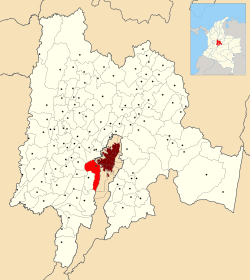

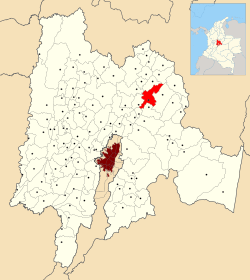

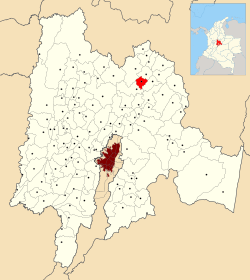

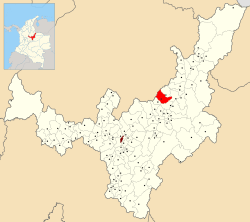

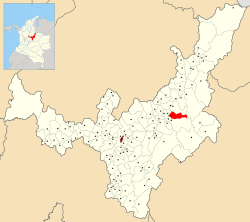

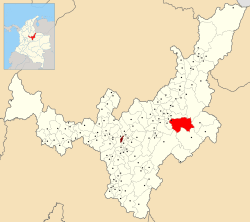

Type | Image | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Abra | Cundinamarca | 2570 | petroglyphs |  |

|

| Facatativá P. del Tunjo |

Cundinamarca | 2611 | petrographs | |

|

| Tenjo | Cundinamarca | 2587 | petrographs |  |

|

| Tibacuy | Cundinamarca | 1647 | petrographs | |

|

| Berbeo | Boyacá | 1335 | petroglyphs | |

|

| Sáchica | Boyacá | 2150 | petrographs | |

|

| Bojacá | Cundinamarca | 2598 | petrographs |  | |

| La Calera | Cundinamarca | 2718 | petrographs |  | |

| Chía | Cundinamarca | 2564 | petrographs |  | |

| Chipaque | Cundinamarca | 2400 | petrographs |  | |

| Cogua | Cundinamarca | 2600 | petrographs |  | |

| Cota | Cundinamarca | 2566 | petrographs |  | |

| Cucunubá | Cundinamarca | 2590 | petrographs |  | |

| Guachetá | Cundinamarca | 2688 | petrographs |  | |

| Guasca | Cundinamarca | 2710 | petrographs |  | |

| Guatavita | Cundinamarca | 2680 | petrographs |  | |

| Machetá | Cundinamarca | 2094 | petrographs |  | |

| Madrid | Cundinamarca | 2554 | petrographs |  | |

| Mosquera | Cundinamarca | 2516 | petrographs |  | |

| Nemocón Checua |

Cundinamarca | 2585 | petrographs |  | |

| San Antonio del Tequendama |

Cundinamarca | 1540 | petrographs |  | |

| San Francisco | Cundinamarca | 1520 | petrographs |  | |

| Sibaté | Cundinamarca | 2700 | petrographs |  | |

| Soacha | Cundinamarca | 2565 | petrographs |  | |

| Subachoque | Cundinamarca | 2663 | petrographs |  | |

| Suesca | Cundinamarca | 2584 | petrographs |  | |

| Sutatausa | Cundinamarca | 2550 | petrographs |  | |

| Tausa | Cundinamarca | 2931 | petrographs |  | |

| Tena | Cundinamarca | 1384 | petrographs |  | |

| Tenjo | Cundinamarca | 2587 | petrographs |  | |

| Tequendama | Cundinamarca | 2570 | petrographs |  | |

| Tibiritá | Cundinamarca | 1980 | petrographs |  | |

| Tocancipá | Cundinamarca | 2605 | petrographs |  | |

| Une | Cundinamarca | 2376 | petrographs |  | |

| Zipacón | Cundinamarca | 2550 | petrographs |  | |

| Zipaquirá | Cundinamarca | 2650 | petrographs |  | |

| Bosa | Cundinamarca | 2600 | petrographs |  | |

| Usme | Cundinamarca | 2600 | petrographs |  | |

| Belén | Boyacá | 2750 | petrographs |  | |

| Gámeza | Boyacá | 2750 | petrographs |  | |

| Iza | Boyacá | 2560 | petrographs |  | |

| Mongua | Boyacá | 2975 | petrographs |  | |

| Motavita | Boyacá | 2690 | petrographs |  | |

| Ramiriquí | Boyacá | 2325 | petrographs |  | |

| Saboyá | Boyacá | 2600 | petrographs |  | |

| Tibaná | Boyacá | 2115 | petrographs |  | |

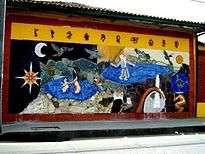

Modern Muisca-based art

In the centre of Bogotá the process of production of tunjos is still alive. Using the same methods as the Muisca must have used, the votive offer figurines are crafted.[37] Artistic representations of Muisca creativity are not as common as the Maya, Aztec and Inca. Still, modern interpretations of their art are produced. In Bosa, a locality in the west of Bogotá, a mural depicts the various deities. Another mural showing the gods and goddesses of the Muisca is made in the Hotel Tequendama, named after preceramic archaeological site and rock shelter Tequendama, in the centre of Bogotá. Other stylistic art of these deities are produced by professional graphic designers in Colombia.[130] The Muisca are featured as one of the playable nations in the videogame Europa Universalis IV, where a specially developed expansion set El Dorado can be played; seven cities of gold in the Americas with the leaders of the main civilisations represented.[131] In the main game, all the Muisca rulers, from Michuá and Meicuchuca till Tisquesusa, Sagipa and Aquiminzaque are included. Conquest of Paradise (DLC), about the conquest of the New World, is another expansion for the world diplomacy and strategy game. Other names are Bacatá, Busbanzá, Cerinza, Charalá, Chipatá, Cuxininegua, Duitama, Guecha, iraca, Onzaga, Paipa, Saboyá, Soacha, Tenza, Tibana, Tibirita, Toca, Tomagata, Tunduma, Tutazúa, Uzathama, zaque, zipa, Tibacuy, Aguazuque and Zipacón.[132] Artist Zamor has published about the Muisca and Colombian-Australian artist María Fernanda Cardoso made a piece about the importance of frogs within the culture, called "Dancing Frogs". IN the 19th century, writer and later Colombian president Santiago Pérez de Manosalbas published a work called Nemequene, about zipa Nemequene.

-

Mural in Bosa showing the different deities in the Muisca religion

-

Modern sculpture of Earth goddess Bachué

-

Statue honouring messenger god Bochica in Cuítiva, Boyacá

-

%2C_mujer_guerrera.jpg)

Representation of a female guecha warrior in Sevilla, Spain

-

Statue of the mythical Goranchacha in Tunja

-

The Colombian beer brand Club Colombia uses a tunjo as symbol

-

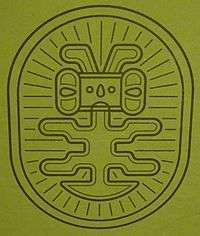

Modern symbol made by the descendants of the Muisca

-

The seal of Guatavita bears a Muisca figure against a shining Sué

See also

References

- 1 2 (Spanish) Siteos arqueológicos - ICANH

- ↑ Argüello García, 2015, p.56

- ↑ Langebaek Rueda, 2005, p.290

- ↑ Lleras et al., 2009, p.183

- ↑ Lleras et al., 2009, p.179

- 1 2 Langebaek Rueda, 2003, p.263

- ↑ Legast, 2000, p.28

- ↑ Legast, 2000, p.29

- ↑ García, 2012, p.133

- ↑ Correal Urrego, 1990, p.80

- ↑ Bohórquez Caldera, 2008, p.170

- ↑ Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.30

- ↑ Bohórquez Caldera, 2008, p.171

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, p.216

- ↑ Langebaek Rueda, 2003, p.264

- ↑ Lleras et al., 2009, p.184

- ↑ (Spanish) Conquista rápida y saqueo cuantioso de Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

- ↑ (Spanish) List of conquistadors led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada - Banco de la República

- ↑ (Spanish) Tunjo - Muysccubun dictionary online

- ↑ (Spanish) Tunjos found in caves and other places

- ↑ Tunjo in American Museum of Natural History

- ↑ Tunjos in the Art Institute Chicago

- ↑ Tunjos in the Baltimore Museum of Art

- ↑ Tunjo in the British Museum

- ↑ Tunjo in the Brooklyn Museum

- ↑ Tunjos in the Cleveland Art Museum

- ↑ Tunjos in the Dallas Museum of Art

- ↑ Tunjo in Hunt Museum

- ↑ Tunjos in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Tunjos in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- ↑ Tunjo in the Princeton University Art Museum

- ↑ Tunjo in the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

- ↑ Londoño, 1989, p.107

- 1 2 3 (Spanish) Description and metallurgy of tunjos - Museo del Oro - Bogotá

- ↑ Sánchez, s.a., p.3

- 1 2 3 Peña Gama, p.8

- 1 2 Cooper & Langebaek Rueda, 2013

- ↑ Londoño, 1989, p.93

- ↑ Londoño, 1989, p.94-117

- ↑ Londoño, 1989, p.98

- ↑ (Spanish) Exposición del Museo del Oro en Bogotá - Banco de la República

- ↑ (Spanish) Explanation of the metallurgy of the Muisca raft by Eduardo Londoño - Museo del Oro

- ↑ Secrets: Golden Raft of El Dorado. Smithsonian Channel. 2013. Event occurs at 27 minutes, 11 seconds.

- ↑ (Spanish) Official website Sesquilé

- ↑ (Spanish) Official website Pasca

- ↑ Langebaek Rueda, 2003, p.265

- ↑ Broadbent, 1974, p.120

- ↑ (Spanish) ca - Muysccubun dictionary online

- ↑ Langebaek Rueda, 1995a, p.8

- ↑ Henderson & Ostler, 2005, p.156

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.203

- ↑ Cardale de Schrimpff, 1985, p.116

- ↑ Henderson & Ostler, 2005, p.157

- ↑ Cristancho Mejía, 2008, p.4

- ↑ Langebaek Rueda, 1995b, Ch.1

- ↑ (Spanish) Temple of the Sun - Sogamoso - Pueblos Originarios

- 1 2 Ortega Loaiza et al., 2012, p.8

- 1 2 Martínez & Martínez, 2012, p.71

- 1 2 3 Martínez & Martínez, 2012, p.68

- ↑ Rodríguez Cuenca, 2007, p.115

- ↑ Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.13

- ↑ Henderson & Ostler, 2005, p.149

- ↑ García, 2012, p.27

- ↑ Martínez & Martínez, 2012, p.74

- 1 2 Martínez & Martínez, 2012, p.72

- ↑ Martínez & Martínez, 2012, p.69

- ↑ (Spanish) Momia - Banco de la República

- ↑ Villa Posse, 1993, p.52

- ↑ (Spanish) Estudio de tumbas Muiscas evoca el mito de la Leyenda del Dorado

- ↑ Martínez Martín, s.a., p.3

- ↑ Correa, 2005, p.204

- ↑ Trimborn, 2005, p.305

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.230

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.231

- ↑ (Spanish) Monotonous music of the Muisca

- ↑ (Spanish) Music of the Muisca - Banco de la República

- ↑ Escobar, 1987

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.221

- ↑ (Spanish) Huitaca, la diosa muisca en el Palacio Liévano - El Tiempo

- ↑ Langebaek Rueda, 2005, p.291

- ↑ Ocampo López, 1970, p.88

- 1 2 3 Fernández Sacama, 2013, p.289

- ↑ Francis, 1993, p.39

- ↑ Fernández Sacama, 2013, p.290

- ↑ Cortés Moreno, 1990, p.62

- ↑ Fernández Sacama, 2013, p.291

- ↑ Cortés Moreno, 1990, p.64

- ↑ Francis, 1993, p.44

- ↑ Fernández Sacama, 2013, p.287

- ↑ Fernández Sacama, 2013, p.288

- ↑ Humboldt, 1807, Part 1

- ↑ (Spanish) Muisca numbers according to Bernardo de Lugo

- ↑ Pineda Camacho, 2005, p.26

- ↑ (Spanish) Los Chibchas o Muiscas

- ↑ Uscategui Mendoza, 1961, p.336

- 1 2 Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.5

- ↑ Rico Ramírez, 2013, p.88

- ↑ Triana, 1922

- ↑ Rico Ramírez, 2013, p.87

- ↑ Rico Ramírez, 2013, p.84

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.2

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.14

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.15

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.16

- ↑ Contreras Díaz, 2011, p.148

- 1 2 Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.17

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.42

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.44

- 1 2 Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.45

- 1 2 Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.55

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.43

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.48

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.49

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.58

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.59

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.63

- ↑ Silva Celis, 1962, p.14

- ↑ Silva Celis, 1962, p.19

- ↑ Silva Celis, 1962, p.20

- ↑ Silva Celis, 1962, p.23

- ↑ Silva Celis, 1962, p.27

- ↑ Martínez & Botiva, 2004b, p.13-14

- 1 2 Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.10

- ↑ Martínez & Botiva, 2004a

- ↑ López Estupiñán, 2011

- ↑ Martínez & Botiva, 2004b, p.15

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.11

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2013, p.23

- ↑ Muñoz Castiblanco, 2006, p.3

- ↑ Guzmán, 2012

- ↑ El Dorado expansion set - Paradox Interactive - Europa Universalis IV

- ↑ Muisca names Europa Universalis IV - GitHub

Bibliography

General Muisca & Herrera

- Argüello García, Pedro María. 2015. Subsistence economy and chiefdom emergence in the Muisca area. A study of the Valle de Tena (PhD), 1–193. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Bohórquez Caldera, Luis Alfredo. 2008. Concepción sagrada de la naturaleza en la mítica muisca - Sacred definition of nature in the Muisca mythology. Franciscanum L. 151-176.

- Broadbent, Sylvia M.. 1974. La situación del Bogotá Chibcha - The Chibcha Bogotá situation. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 17. 117-132.

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. 1985. En busca de los primeros agricultores del Altiplano Cundiboyacense - Searching for the first farmers of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 99–125. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Correa, François. 2005. El imperio muisca: invención de la historia y colonialidad del poder - The Muisca empire: invention of history and power colonialisation, 201-226. Universidad La Javeriana.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque - evidencias de cazadores, recolectores y plantadores en la altiplanicie de la Cordillera Oriental - Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1-316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Francis, John Michael. 1993. "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (M.A.), 1-118. University of Alberta.

- García, Jorge Luis. 2012. The Foods and crops of the Muisca: a dietary reconstruction of the intermediate chiefdoms of Bogotá (Bacatá) and Tunja (Hunza), Colombia (M.A.), 1–201. University of Central Florida. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2007. Grandes culturas indígenas de América - Great indigenous cultures of the Americas, 1–238. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Rodríguez Cuenca, José Vicente. 2006. Las enfermedades en las condiciones de vida prehispánica de Colombia - La alimentación prehispánica - The diseases in the prehispanic living conditions of Colombia - the prehispanic food, 83–128. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Sánchez, Efraín. s.a.. Muiscas, 1-6. Museo del Oro. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Trimborn, Hermann. 2005. La organización del poder público en las culturas soberanas de los chibchas - The public power organisation in the common cultures of the Chibchas, 298-314. Universidad La Javeriana.

- Villa Posse, Eugenia. 1993. Mitos y leyendas de Colombia - Volumen III - Myths and legends of Colombia - Volume 3, 1-160. IADAP.

Goldworking

- Cooper, Jago, and Carl Henrik Langebaek Rueda. 2013. The Lost Kingdoms of South America - Episode 3 - Lands of Gold. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 2003. The Political Economy of Pre-Colombian Goldwork: Four Examples from Northern South America, 245–278. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C..

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1995a. Heterogeneidad vs. homogeneidad en la arqueología colombiana: una nota crítica y el ejemplo de la orfebrería - Heterogeneity vs. homogeneity in the Colombian achaeology: a critical note and the example of the metallurgy. Revista de antropolog;ia y arqueología 11. 3-36.

- Legast, Anne. 2000. La figura serpentiforme en la iconografía muisca. Boletín Museo del Oro 46. 22-39.

- Lleras, Roberto; Javier Gutiérrez, and Helena Pradilla. 2009. Metalurgia temprana en la Cordillera Oriental de Colombia - Early metallurgy in the Eastern Cordillera, Colombia. Boletín de Antropología 23. 169-185.

- Londoño, Eduardo. 1989. Santuarios, santillos, tunjos: objetos votivos de los Muiscas en el siglo XVI, 92-120.

- Pineda Camacho, Roberto. 2005. Laberinto de la identidad - símbolos de transformación y poder en la orfebrería prehispánica en Colombia, 16-92.

Architecture

- Cristancho Mejía, Ana. 2008. Importancia de los caminos ancestrales en su medio ambiente en el pueblo de Iza, Boyacá, 1-4.

- Henderson, Hope, and Nicholas Ostler. 2005. Muisca settlement organization and chiefly authority at Suta, Valle de Leyva, Colombia: A critical appraisal of native concepts of house for studies of complex societies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 24. 148–178.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1995b. Los caminos aborígenes - The indigenous roads. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

Mummies

- Martínez Martín, Abel Fernando, and Luz Martínez Santamaría. 2012. Sobre la momificación y los cuerpos momificados de los muiscas - On mummification and the mummified bodies of the Muisca. Revista Salud Historia Sanidad 1. 61-80.

- Ortega Loaiza, Natalia; Diana Fernanda Grisales Cardona; Alejandra Uribe Botina, and Juan Camilo Blandón Hernández. 2012. Los rituales fúnebres indígenas - The indigenous burial rituals, 1-15.

Music

- Escobar, Luis Antonio. 1987. La música en Santa Fé de Bogotá - las mozcas - The music in Santa Fé de Bogotá - the Muisca. Museo del Oro. Accessed 2016-07-08.

Ceramics and textiles

- Cortés Moreno, Emilia. 1990. Mantas Muiscas, 60-75.

- Fernández Sacama, Martha. 2013. La manta Muisca como objeto de evocación - The Muisca Manta as an evocation object. KEPES 9. 285-296.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 1970. La artesanía popular boyacense y su importancia en la geografía turística y económica. El Correo Geográfico 1. 87–92.

- Peña Gama, Claudia. s.a.. Diseño precolumbino Muisca, 1-11.

- Uscategui Mendoza, Nestor. 1961. Algunos colorantes vegetales usados por las tribus indígenas de Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 10. 332-340.

Numerals and archaeoastronomy

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 1 - Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas - Muisca calendar - Part 1. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2009. The Muisca Calendar: An approximation to the timekeeping system of the ancient native people of the northeastern Andes of Colombia (PhD), 1-170. Université de Montréal. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 2005. Fiestas y caciques muiscas en el Infiernito, Colombia: un análisis de la relación entre festejos y organización política - Festivities and Muisca caciques in El Infiernito, Colombia: an analysis of the relation between celebrations and political organisation. Boletín de Arqueología 9. 281–295.

Rock art

- Contreras Díaz, Federmán. 2011. Relationship between the Muisca rock art and the lexicon, 142-150. XXIV Valcamonica Symposium.

- López Estupiñán, Laura. 2011. Topando piedras, sumercé. Narraciones en torno a las piedras de Iza y Gámeza, Boyacá, Colombia - Bumping into stones, mister. Tales around the stones of Iza and Gámeza, Boyacá, Colombia (M.A.). 2; Rupestreweb. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Martínez Celis, Diego, and Álvaro Botiva Contreras. 2004a. Manual de arte rupestre de Cundinamarca - Manual of rock art of Cundinamarca, 1-60. ICANH.

- Martínez Celis, Diego, and Álvaro Botiva Contreras. 2004b. Introducción al arte rupestre, 1-28. ICANH.

- Muñoz Castiblanco, Guillermo. 2013. Catalogación, registro sistemático y diagnóstico de las pinturas rupestres del Parque Arqueológico de Facatativá, 1-89. GIPRI.

- Muñoz Castiblanco, Guillermo. 2006. Pinturas rupestres en el Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia - concentración y diversidad en la Sabana de Bogotá: Municipio de Suacha-Sibaté Cundinamarca - Rock paintings on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia - concentration and diversity on the Bogotá savanna: municipality of Soacha-Sibaté, Cundinamarca, 1-22.

- Rico Ramírez, Mónica Sofía. 2013. Arte rupestre muisca, cultura e ingenio humano - Muisca’s ruspestrian art, culture and human wit. Revista de Tecnología 12. 83-90.

- Silva Celis, Eliécer. 1962. Pinturas rupestres precolombinas de Sáchica, Valle de Leiva - Pre-Columbian rock art of Sáchica, Leyva Valley. Revista Colombiana de Antropología X. 9-36. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Triana, Miguel. 1922. La civilización Chibcha, 1–222. Accessed 2016-07-08.

Modern Muisca-based art

- Guzmán, Daniel. 2012. Demonios & Deidades Muiscas. Accessed 2016-07-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muisca art. |

- (Spanish) Muisca art - Museo del Oro, Bogotá

- (Spanish) Muisca art - Pueblos Originarios