Presidency of Warren G. Harding

The presidency of Warren G. Harding began on March 4, 1921, when Warren G. Harding was inaugurated as the 29th President of the United States, and ended when he died on August 2, 1923, a span of 881 days. Harding's presidency occurred during a period in American political history from the mid–1890s to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, excepting after the 1912 split when Democrats held the White House for eight years. American history texts usually call it the Progressive Era.

Harding's 26.2 percentage-point victory (60.3% to 34.1%) in the 1920 presidential election remains the largest popular-vote percentage margin in presidential elections after the so-called "Era of Good Feelings" ended with the unopposed election of James Monroe in 1820. Harding's 60.3% of the popular vote was also the greatest percentage since 1820, but was later exceeded by Franklin Roosevelt in 1936, Lyndon Johnson in 1964, and Richard Nixon in 1972.

As president, he appointed a number of well-regarded figures, including Andrew Mellon at the Treasury, Herbert Hoover at Commerce, and Charles Evans Hughes at the State Department. A major foreign policy achievement came with the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922, in which the world's major naval powers agreed on a naval limitations program that lasted a decade. Two members of his cabinet were implicated in corruption: Interior Secretary Albert Fall and Attorney General Harry Daugherty.

Harding died of a cerebral hemorrhage caused by heart disease in San Francisco while on a western speaking tour; he was succeeded by his Vice President, Calvin Coolidge. Although he died one of the most popular presidents in history, the subsequent exposure of scandals that took place under him, such as Teapot Dome, eroded his popular regard, as did revelations of an affair by Nan Britton, one of his mistresses. In historical rankings of the U.S. presidents, Harding is often rated among the worst.

Presidential election of 1920

Republican nomination

In 1918, when Theodore Roosevelt was entertaining plans (cut short by his death in January 1919) to reprise his presidency, he considered Harding as having strong potential to run and serve as Vice President, and discussed with Harry Daugherty the desirability of having Harding on his ticket.[1] In 1919, the first candidate to declare for the GOP nomination was General Leonard Wood. The GOP bosses were nevertheless determined to have a dependable listener, and were lukewarm toward the General.[2] Some in the party began to scout for such an alternative, and Harding's name arose, despite his reluctance, due to his unique ability to draw vital Ohio votes.[3] Also at the forefront of a throng of candidates for the nomination were Hiram Johnson, Frank Lowden and Herbert Hoover.[4] Harry Daugherty, who became Harding's campaign manager, and who was sure none of these candidates could garner a majority, convinced Harding to run after a marathon discussion of six-plus hours.[5] Daugherty's campaign style was variously described as pugnacious, devious and no holds barred.[6] For example, shortly before the GOP convention, Daugherty struck a deal with millionaire and political opportunist Jake Hamon, whereby 18 Oklahoma delegates whose votes Hamon had bought for Lowden were committed to Harding as a second choice if Lowden's effort faltered.[7][8]

Harding's supporters thought of him as the next McKinley. By the time the convention began, a Senate sub-committee had tallied the monies spent by the various candidates, with totals as follows: Wood—$1.8 million; Lowden—$414,000; Johnson—$194,000; and Harding—$114,000; the committed delegate count at the opening gavel was: Wood—124; Johnson—112; Lowden—72; Harding—39.[9] Still, at the opening, less than one-half of the delegates were committed.[10] No candidate was able to corral a majority after nine ballots.[11] Republican Senators and other leaders, who were divided without a singular political boss, met in Room 404 of the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago and after a nightlong session, tentatively concluded Harding was the best possible compromise candidate. According to Francis Russell, though additional meetings took place, this particular meeting came to be known as the "smoke filled room".[12] Before Harding received the formal nod, George Harvey summoned him. Harvey told him he was considered the consensus nominee, and asked if he knew, "before God," whether anything in his life would be an impediment. After mulling the question over for some minutes, Harding replied no, despite his alleged adulterous affairs.[13] The next day, when Harding was nominated on the tenth ballot, Mrs. Harding was so startled, she inadvertently stabbed Harry Daugherty in the side with her hatpins.[14] The local Masons could not resist the opportunity to co-opt Harding's new status, and promoted him to the Sublime Degree of a Master Mason.[15]

General election

In the 1920 election, Harding ran against Democratic Ohio Governor James M. Cox, whose running mate was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. The election theme became a rejection of the "progressive" ideology of the Woodrow Wilson Administration in favor of the "laissez-faire" approach of the William McKinley era.[16]

Harding ran on a promise to "Return to Normalcy", a seldom-used term he popularized, and healing for the nation after World War I. The policy called for an end to the abnormal era of the Great War, along with a call to reflect three trends of the time: a renewed isolationism in reaction to the War, a resurgence of nativism, and a turning away from government activism.[17]

On July 28, 1920, Harding's aide Albert Lasker, a top advertising executive from Chicago, unleashed a broad-based advertising campaign that used modern advertising techniques for the first time in a presidential campaign.[18] Lasker's approach included newsreels and sound recordings, all in an effort to enhance Harding's patriotism and affability. Farmers were sent brochures decrying the alleged abuses of Democratic agriculture policies. African Americans and women were also given literature in an attempt to take away votes from the Democrats. Professional advertisers including Chicagoan Albert Tucker were consulted. Billboard posters, newspapers and magazines were employed in addition to motion pictures. Five thousand speakers were trained by advertiser Harry New and sent abroad to speak for Harding; 2,000 of these speakers were women. Telemarketers were used to make phone conferences with perfected dialogues to promote Harding. Lasker had 8,000 photos distributed around the nation every two weeks of Harding and his wife.[19]

Lasker designed the "front porch campaign" during the late summer and fall of 1920 that put Harding's name and image everywhere. It was the first front porch campaign since McKinley in 1896, and the first to receive widespread newsreel coverage. It was also the first modern campaign to use the power of Hollywood and Broadway stars, who travelled to Marion for photo opportunities with Harding and his wife. Al Jolson, Lillian Russell, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford were among the luminaries to make the pilgrimage to his house in central Ohio. Business icons Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone also lent their cachet to the campaign. From the onset of the campaign until the November election, over 600,000 people travelled to Marion to participate.

The campaign owed a great deal to Florence Harding, who played a more active role than the wives of previous candidates had. She cultivated the relationship between the campaign and the press. As the business manager of the Star, she understood reporters and their industry. She played to their needs by being available to answer questions, pose for pictures, or deliver food from her kitchen to the press office—a bungalow that she had constructed at the rear of their property in Marion. Mrs. Harding even coached her husband on the proper way to wave to newsreel cameras to make the most of coverage.

Campaign manager Lasker struck a deal with Harding's paramour, Carrie Phillips, and her husband Jim Phillips, whereby the couple agreed to leave the country until after the election. Ostensibly, Mr. Phillips was to investigate the silk trade.[20]

The campaign also drew on Harding's popularity with women. Considered handsome, Harding photographed well compared to Cox. However, it was mainly Harding's Senate support for women's suffrage legislation that made him popular in that demographic. Ratification of the 19th Amendment in August 1920 brought huge crowds of women to Marion, Ohio to hear Harding speak. Immigrant groups such as ethnic German Americans and Irish Americans, who made up an important part of the Democratic coalition, also voted for Harding, in reaction to the nation's persecution of the Germans during and after the war and Wilson's retraction of support for Irish independence.

The 1920 election was the first in which women could vote nationwide, and the first to be covered on the radio, thanks to KDKA ("8ZZ") in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 8MK (later WWJ) in Detroit, and the educational and amateur radio station 1XE (later WGI) at Medford Hillside, Massachusetts – all of which carried the election returns. Harding received 60% of the national vote, the highest percentage ever recorded up to that time, and 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34% of the national vote and 127 electoral votes.[21] Campaigning from a federal prison, Socialist Eugene V. Debs received 3% of the national vote. The Presidential election results of 1920, for the first time in U.S. history, were announced live by radio.[22] Harding was the only Republican presidential candidate to ever defeat Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt on a presidential ticket. At the same time, the Republicans picked up an astounding 63 seats in the House of Representatives.[23] Harding immediately embarked on a vacation that included an inspection tour of facilities in the Panama Canal Zone.[24]

African-American lineage contention

During the campaign, Democratic opponents spread rumors that Harding's great-great-grandfather was a West Indian black person and that other blacks might be found in his family tree.[25] In an era when the "one-drop rule" would classify a person with any African ancestry as black, and black people in the South had been effectively disfranchised, Harding's campaign manager responded, "No family in the state (of Ohio) has a clearer, a more honorable record than the Hardings', a blue-eyed stock from New England and Pennsylvania, the finest pioneer blood."[16]

Historian and opponent William Estabrook Chancellor publicized the rumors, based on supposed family research, but perhaps reflecting no more than local gossip.[26] The rumors may have been sustained by a statement Harding allegedly made to newspaperman James W. Faulkner on the subject, which he perhaps meant to be dismissive: "How do I know, Jim? One of my ancestors may have jumped the fence."[27] However, while there are gaps in the historical record, studies of his family tree have not found evidence of an African-American ancestor.[28]

Presidency: 1921–1923

Harding preferred a low-key inauguration, without the customary parade, leaving only the swearing-in ceremony and a brief reception at the White House. In his inaugural speech he declared, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it."[29] Literary critic H.L. Mencken was appalled, announcing that:

- He writes the worst English I have ever encountered. It reminds me of a string of wet sponges; it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights.[30]

The Hardings brought a different style to the running of the White House. Though Mrs. Harding did keep a little red book of those who had offended her, the executive mansion was now once again open to the public for events including the annual Easter egg roll.[31] Harding's administration followed the Republican national platform. Energized by his landslide, Harding felt the "pulse" of the nation and for the 28 months in office he remained popular both nationally and internationally. Harding's administration has been critically viewed due to multiple scandals, while his successes in office were often given credit to his capable cabinet appointments that included future President Herbert Hoover. Author Wayne Lutton asked, "Was Harding really a failure?", citing former Watergate persona John Dean, who grew up near Harding's home, as saying Harding's accomplishments included income tax and federal spending reductions, economic policies that reduced "stagflation", a reduction of unemployment by 10%, and a bold foreign policy that created peace with Germany, Japan, and Central America,[32] although Dean's work itself only cites a "slight decline in unemployment figures" and does not mention "stagflation" at all.[33] Herbert Hoover, while serving in Harding's cabinet, was confident the President would serve two terms and return the world to normalcy. Later, in his own memoirs, he stated that Harding had "neither the experience nor the intellect that the position needed."[34] One of Harding's most important decisions was the appointment of former President William Howard Taft as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, a position Taft had always coveted, more so than the Presidency.[35]

Harding pushed for the establishment of the Bureau of Veterans Affairs (later organized as the Department of Veterans Affairs), the first permanent attempt at answering the needs of those who had served the nation in time of war.[36] In April 1921, Harding spoke before a special joint session of Congress that he had called. He argued for peacemaking with Germany and Austria, emergency tariffs, new immigration laws, regulation of radio and trans-cable communications, retrenchment in government, tax reduction, repeal of wartime excess profits tax, reduction of railroad rates, promotion of agricultural interests, a national budget system, an enlarged merchant marine, and a department of public welfare.[37] He also called for measures to end lynching, but not wanting to make enemies in his own party and with the Democrats, he did not fight for his program.[38] Generally, there was a lack of strong leadership in the Congress and, unlike his predecessors Roosevelt and Wilson, Harding was not inclined to fill that void.[39]

According to biographers, Harding got along better with the press than any other previous President, being a former newspaperman. Reporters admired his frankness, candor, and his confessed limitations. He took the press behind the scenes and showed them the inner circle of the presidency. Harding, in November 1921, also implemented a policy of taking written questions from reporters during a press conference.[40] Harding's relationship with Congress, however, was strained and he did not receive the traditional honeymoon given to new Presidents. Before Harding's election, the nation had been adrift; President Woodrow Wilson had been ill by a debilitating stroke for 18 months and before that Wilson had been in Europe for several months attempting to negotiate a peace settlement after World War I. By contrast, at the March 4, 1921 Inaugural, Harding looked strong, with grey hair and a commanding physical presence.[40] Wilson's successor stressed the importance of the ceremonial aspects of the office of President. This emphasis fulfilled his desire to travel the breadth of the country to officiate at formal functions.[41]

Although Harding was committed to putting the "best minds" on his cabinet, he often rewarded those persons who were active and contributed to his campaign by appointing them to high federal department positions. Wayne Wheeler, leader of the Anti-Saloon League, was allowed by Harding to dictate who would serve on the Prohibition Commission.[42] Graft and corruption charges permeated Harding's Department of Justice; bootleggers confiscated tens of thousands cases of whiskey through bribery and kickbacks.[43] Harding, out of loyalty, appointed Harry M. Daugherty to U.S. Attorney General because he felt he owed Daugherty for running his 1920 campaign. After the election, many people from the Ohio area moved to Washington, D.C., made their headquarters in a little green house on K Street, and would be eventually known as the "Ohio Gang".[44] The financial and political scandals caused by these men, in addition to Harding's own personal controversies, severely damaged Harding's personal reputation and eclipsed his presidential accomplishments. In his most open challenge to Congress, Harding forced a deferral of a budget-busting World War I soldier's bonus in an effort to reduce costs.[45]

A 2008 study of presidential rankings for The Times placed Harding at number 34[46] and a 2009 C-SPAN survey ranked Harding at 38.[47] In 2010, a Siena College poll of Presidential scholars placed Harding at 41. The same poll ranked Harding 26 in the Ability to Compromise category.[48]

Harding presided over the nation's initial consecration of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. This followed similar commemorations established by Britain, France and Italy. The fallen hero was chosen from a group previously interred at Romagne Military Cemetery in France, and was re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

On December 23, 1921 Harding calmed the 1919–1920 Bolshevik scare, and released an election opponent, socialist leader Eugene Debs, from prison. This was part of an effort to return the United States to normalcy after the Great War. Debs, a forceful World War I antiwar activist, had been convicted under sedition charges brought by the Wilson administration for his opposition to the draft during World War I.[49] Despite many political differences between the two candidates Harding commuted Debs' sentence to time served; however, he was not granted an official Presidential pardon. Debs' failing health was a contributing factor for the release. Harding granted a general amnesty to 23 prisoners, alleged anarchists and socialists, active in the Red Scare.[36][50]

Harding's party suffered the loss of 79 seats in the House in the 1922 mid-term elections, leaving them with a razor-thin majority.[51] The President determined to fill the void of leadership in the party and attempted to take a more aggressive role in setting the legislative agenda.[52]

The Hardings visited their home community of Marion, Ohio, once during the term, when the city celebrated its centennial during the first week of July. Harding arrived on July 3, gave a speech to the community at the Marion County Fairgrounds on July 4, and left the following morning for other speaking commitments.

Joint Session of Congress 1921

On April 12, Harding called a joint session of Congress to address matters that he deemed of national and urgent importance. That speech, considered his best, contained few political platitudes and was enthusiastically received by Congress. On the economic front, Harding urged Congress to create a Bureau of the Budget, cut expenditures, and revise federal tax laws. Harding urged increased protectionist tariffs, lower taxes, and agriculture legislation to help farmers. In the speech, Harding advocated aviation technology for civil and military purposes, development and regulation of radio technology, and passage of a federal anti-lynching law to protect African Americans. Harding advocated, in terms of foreign affairs, a "conference and cooperation" of nations to prevent war—yet flatly stated that the U.S. should not enter the League of Nations. Harding endorsed peace between all former enemy nations from World War I and the funding and liquidation of war debts.[36]

Domestic and Economic policies

Bureau of the Budget and Veterans Bureau

Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, considered one of his greatest domestic and enduring achievements.[53] Harding got authorization from Congress for the country's first formal budgeting process—establishing of the Bureau of the Budget.[54] The law created the position of presidential budget director, who was directly responsible to the President rather than to the Secretary of Treasury. The law also stipulated that the President must annually submit a budget to the U.S. Congress, and all presidents since have had to do so.[55] The General Accounting Office was created to assure oversight in the federal budget expenditures. Harding appointed Charles Dawes as the Bureau of the Budget's first director. Known for his position as an effectrive financier, Dawes reduced government spending by $1.5 billion his first year as director, a 25% reduction, along with another 25% reduction the following year. In effect, the Government budget was nearly cut in half in just two years.[56]

Harding believed the federal government was supposed to be fiscally managed in a way similar to private sector businesses. He had campaigned on the slogan, "Less government in business and more business in government."[57] Harding was true to his word, carrying on budget cuts that had begun under a debilitated Woodrow Wilson. Federal spending declined from $6.3 billion in 1920 to $5 billion in 1921 and $3.3 billion in 1922. Tax rates, meanwhile, were slashed—for every income group. And over the course of the 1920s, the national debt was reduced by one third.[58]

On August 9, 1921, Harding signed the Sweet Bill, which established the a new agency known as the Veterans Bureau. After World War I, 300,000 wounded veterans were in need of hospitalization, medical care, and job training. To handle the needs of these veterans, the new agency incorporated the War Risk Insurance Bureau, the Brig. Gen. Charles E. Sawyer's Federal Hospitalization Bureau, along with three other bureaus that dealt with veteran affairs.[59] Harding regrettably appointed Colonel Charles R. Forbes, albeit a decorated war veteran, as the Veteran Bureau's first director (see scandal below), a position that reported directly to the President. The Veterans Bureau later was incorporated into the Veterans Administration and ultimately the Department of Veterans Affairs.[60]

Postwar recession and recovery

On March 4, Harding assumed office while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline, known as the Depression of 1920–21. By the summer of his first year in office, an economic recovery began. He convened the Conference of Unemployment in 1921, headed by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, that proactively advocated stimulating the economy with local public work projects and encouraged businesses to apply shared work programs.[61] Harding's Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, ordered a study that claimed to demonstrate that as income tax rates were increased, money was driven underground or abroad. Mellon concluded that lower rates would increase tax revenues. Based on this advice, Harding began cut taxes in 1922. The top marginal rate was annually reduced in four stages from 73% in 1921 to 25% in 1925. Taxes were cut for lower incomes, starting in 1923.[62]

Revenues to the treasury decreased substantially.[63] Libertarian historian Thomas Woods contends that the tax cuts ended the Depression of 1920–1921.[58] Historians Schweikart and Allen also attribute this to the tax cuts.[64] They argue that Harding's tax and economic policies in part "... produced the most vibrant eight year burst of manufacturing and innovation in the nation's history,"[65] though the recession had already ended three months into Harding's first term (before taxes were cut) and was yet again in recession by 1923.[66] Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains during the 1920s. Daniel Kuehn has attributed the improvement to the earlier monetary policy of the Federal Reserve, and notes that the changes in marginal tax rates were accompanied by an expansion in the tax base that could account for the increase in revenue.[67]

Robert Gordon, a Keynesian, notes, "government policy to moderate the depression and speed recovery was minimal. The Federal Reserve authorities were largely passive. ... Despite the absence of a stimulative government policy, however, recovery was not long delayed." Kenneth Weiher, an economic historian, notes, "despite the severity of the contraction, the Fed did not move to use its powers to turn the money supply around and fight the contraction." He concedes that "the economy rebounded quickly from the 1920–1921 depression and entered a period of quite vigorous growth."[58] Paul Krugman argues that the monetary base expanded significantly from 1922 to 1925, and that this expansion was accompanied by a reduction in commercial paper rates.[68] Allan Meltzer agrees that the rising real money stock motivated wealth owners to invest.[69] Recovery did not last long. Another economic contraction began near the end of Harding's presidency in 1923, while tax cuts were still underway. A third contraction followed in 1927 during the next presidential term.[66]

Farm acts and Radio Conferences

Between 1921 and 1922, Harding signed a series of bills regulating agriculture. The legislation emanated from President Woodrow Wilson's 1919 Federal Trade Commission report, which investigated and discovered "manipulations, controls, trusts, combinations, or restraints out of harmony with the law or the public interest" in the meat packing industry. The first law was the Packers and Stockyards Act, which prohibited packers from engaging in unfair and deceptive practices. Two amendments were made to the Farm Loan Act of 1916 that President Wilson had signed into law, which had expanded the maximum size of rural farm loans. The Emergency Agriculture Credit Act authorized new loans to farmers to help them sell and market livestock. The Capper–Volstead Act, signed by Harding on February 18, 1922, protected farm cooperatives from anti-trust legislation. The Future Trading Act was also enacted, regulating puts and calls, bids, and offers on futures contracting. Later, on May 15, 1922, the Supreme Court ruled this legislation unconstitutional.[36]

On February 27, 1922, Harding implemented the first of a series of Radio Conferences headed by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. The last Radio Act of 1912 was considered "inadequate" and "chaotic"; change was necessary to help the fledgling radio industry. At the first meeting, 30 representatives—including amateurs, governmental agencies, and the radio industry made "cooperative efforts" to ensure the public interest in broadcasting, who would broadcast, and for what purpose, and to curb direct advertising. Also discussed was how wattage power used by broadcasters would be distributed depending on the radio station's conditional use and location.[70]

A second radio conference was called in 1923, and this time Secretary Hoover successful obtained radio regulation power without legislation. Hoover himself, in January 1923, told the press there was an, "...urgent need for radio regulation." Large radio stations such as Westinghouse advocated that only 25 larger radio stations in large metropolitan areas be allowed to broadcast, while smaller stations would be given limited power. At the end of the meeting, the industrialists agreed to give Hoover the power to, "...regulate hours and wave lengths of operation of stations when such action is necessary to prevent interference detrimental to the public good."[70]

Harding became the first president to have a radio in his office, when on February 8, 1922, he had a radio set installed in the White House so he could listen to news and music as his schedule permitted.[71] On June 14, Harding was also the first president that the American public heard on the new mass medium. He spoke on radio at a dedication site in honor of Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words to the Star Spangled Banner.[22]

Revenue Act and Highway Act of 1921

On November 22, 1921, Harding signed the Revenue Act of 1921, which greatly reduced taxes for the wealthiest Americans. Protests from Republican farmers caused the deductions to be less than Secretary of Treasury Andrew Mellon desired. The lengthy 96-page Act reduced the corporate tax from 65% to 50% and provided for ultimate elimination of the excess-profits tax during World War I.[36][72]

The 1920s were a time of modernization for America. To improve and expand the nation's highway system, Harding signed the Federal Highway Act of 1921. From 1921 to 1923, the federal government spent $162 million on America's highway system, infusing the U.S. economy with a large amount of capital.[73] In 1922, Harding proclaimed that America was in the age of the "motor car". He stated that the automobile, "reflects our standard of living and gauges the speed of our present-day life."[74]

Fordney–McCumber Tariff

On September 21, 1922, Harding enthusiastically signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act.[75] The protectionist legislation was sponsored by Representative Joseph W. Fordney and Senator Porter J. McCumber. It increased the tariff rates contained in the previous Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act of 1913, to the highest level in the nation's history. Harding became concerned when the agriculture business suffered economic hardship from the high tariffs. Previously, on May 21, 1921, Harding had signed emergency legislation that put tariffs on select foreign inputs. By 1922, Harding began to realize that the long-term effects of tariffs could be detrimental to national economy, despite the short-term benefits.[51] His successors, Coolidge and Hoover, advocated tariff legislation. The tariffs established in the 1920s have historically been viewed as a contributing factor to causing the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[36][76]

Foreign policies

Harding was very specific in commenting on the appointment of Secretary of State Charles E. Hughes, that the secretary would be the sole spokesman for the State Department (as opposed to the Wilson administration).[77] The U.S. Senate had refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles in both 1919 and 1920 because it required the U.S. to endorse the League of Nations.[36] Hughes worked behind the scenes to formally make peace with Germany and the successor states to Austria-Hungary, Austria and Hungary. This began with the Knox–Porter Resolution. The U.S.–German Peace Treaty, U.S.–Austrian Peace Treaty and U.S.–Hungarian Peace Treaty were ratified in 1921.

Washington arms conference and treaties 1921–1922

Harding spearheaded, with the urging of the Senate, a monumental global conference, held in Washington, D.C., to limit the armaments of world powers, including the U.S., Japan, Great Britain, France, Italy, China, Belgium, Netherlands and Portugal.[78] Harding's Secretary of State, Charles E. Hughes, assumed a primary role in the conference and made the pivotal proposal—the U.S would reduce its number of warships by 30 if Great Britain decommissioned 19, and Japan 17 ships.[79] Starting on November 6, 1921 and ending February 6, 1922, world leaders met to control a naval arms race and to bring stability to East Asia. The conference enabled the great powers to potentially limit their large naval deployment and avoid conflict in the Pacific. The delegation of nations also worked out security issues and promoted cooperation in the Far East.

The conference produced six treaties and twelve resolutions among the participating nations, which ranged from limiting the size or "tonnage" of naval ships to custom tariffs. The treaties, which easily passed the Senate, also included agreements regulating submarines, dominions in the Pacific, and dealings with China.[80] The treaties only remained in effect until the mid-1930s, however, and ultimately failed. Japan eventually invaded Manchuria and the arms limitations no longer had any effect. The building of "monster warships" resumed and the U.S. and Great Britain were unable to quickly rearm themselves to defend an international order and stop Japan from remilitarizing.[81][82]

Harding, in an effort to improve U.S. relations with Mexico, Latin America, and the Caribbean Islands implemented a program of military disengagement. On April 20, 1921, the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia was ratified by the Senate and signed by Harding; that awarded $25,000,000 as indemnity payment for land used to make the Panama Canal.[36]

Harding stunned the capital when he sent to the Senate a message supporting the participation of the U.S. in the proposed Permanent Court of International Justice. This was not favorably received by Harding's colleagues; a resolution was nevertheless drafted, in deference to the President, and then promptly buried in the Foreign Affairs Committee.[83]

Civil rights, labor disputes and strikes

When the governor of West Virginia Ephraim Morgan in 1921 requested federal troops to stop miners who were battling state police and militia, Harding issued two proclamations to keep the peace. Finally he sent in an Army unit who ended the mini-war.[84]

Great railway strike and repeal of 12-hour workday

A year after Harding contended with the 1921 mining labor war in West Virginia, a strike broke out during the summer of 1922 in the railroad industry. On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad workers and shopmen went on strike over hourly wages reduced by seven cents and a 12 hour-day workweek.[85] Strike busters were brought in to fill the positions. Harding proposed a settlement that gave the shop workers some concessions; however, the railroad owners objected. Harding sent out the National Guard and 2,200 deputy U.S. marshals to keep the peace. Attorney General Daugherty convinced Judge James H. Wilkerson to issue a broad sweeping injunction to break up the strike.[86] This was known as the "Wilkerson" or "Daugherty" injunction, which enraged the union as well as many in congress, as it prohibited First Amendment rights.[87] Harding had Daugherty and Wilkerson withdraw the objectionable parts of the injunction. The injunction ultimately succeeded in ending the strike; however, tensions remained high between railroad workers and company men for years. Daugherty's harsh injunction against labor created great discord in Harding's cabinet. This, along with Daugherty's other activities, prompted one Minnesota congressman, Oscar Keller, to unsuccessfully attempt to bring impeachment charges against the Attorney General.[88]

In 1922, Harding and Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover convened a White House conference with manufacturers and unions, to reduce the length of the 12-hour workday, in a move for the cause of labor. The labor movement supported an 8-hour day and a 6-day workweek. Harding wrote Judge Gary, head of US Steel, advocating labor reform. The labor conference, however, decided against labor's demands in 1923. Both Harding and Hoover were disappointed with the committee's ruling. Harding wrote a second letter to Gary and with public support the steel industry repealed the 12-hour work day to an eight-hour work day.[89]

Anti-lynching movement and immigration

Notably in an age of severe racial intolerance during the 1920s, Harding did not hold any racial animosity, according to historian Carl S. Anthony.[90] In a speech on October 26, 1921, given in segregated Birmingham, Alabama Harding advocated civil rights for African Americans; the first President to openly advocate black political, educational, and economic equality during the 20th century.[90] In the "Birmingham speech," Harding wanted African Americans to have equal educational opportunities and greater voting rights in the South. The white section of the audience listened in silence while the black section of the segregated audience cheered.[91] Harding went further and viewed the race problem as a national and international issue and desired that the sectionalism of the Solid South and black membership of the Republican party be broken up.[92] Harding, however, openly stated that he was not for black social equality in terms of racial mixing or intermarriage.[92] Harding also spoke on the Great Migration, believing that blacks migrating to the north and west to find employment had actually harmed race relations between blacks and whites.[92]

He named some African Americans to federal positions, such as Walter L. Cohen of New Orleans, Louisiana, whom he named comptroller of customs. Harding also advocated the establishment of an international commission to improve race relations between whites and blacks; however, strong political opposition by the Southern Democratic bloc prevented the commission. The Ku Klux Klan had its highest membership during its revival in the early 1920s.

Harding supported Congressman Leonidas Dyer's federal anti-lynching bill, known as the Dyer Bill, which passed the House of Representatives on January 26, 1922. The bill was defeated in the Senate by a Democratic filibuster.[93] Harding had previously spoken out publicly against lynching on October 21, 1921. Congress had not debated a civil rights bill since the 1890 Federal Elections Bill.

The Per Centum Act of 1921 signed by Harding on May 19, 1921, reduced the numbers of immigrants to 3% of a country's represented population based on the 1910 census. The Act allowed unauthorized immigrants to be deported. Harding and Secretary of Labor James Davis believed that enforcement had to be humane. Harding often allowed exceptions granting reprieves to thousands of immigrants.[94]

Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act

On November 21, 1921, Harding signed the Sheppard–Towner Maternity Act, the first major federal government social welfare program in the U.S. The law funded almost 3,000 child and health centers throughout the U.S. Medical doctors were spurred to offer preventative health care measures in addition to treating ill children. Doctors were required to help healthy pregnant women and prevent healthy children from getting sick. Child welfare workers were sent out to make sure that parents were taking care of their children. The law was sponsored by Julia Lathrop, America's first director of the U.S. Children's Bureau. Although the law remained in effect only eight years, it set the trend for New Deal social programs during the 1930s. Many women who had been given the right to vote in 1920, were given career opportunities as welfare and social workers.[95][96]

Religious toleration

Harding was tolerant towards other religious faiths. He appointed prominent Rabbi Joseph S. Kornfeld and Father Joseph M. Denning, to foreign diplomatic positions. He also appointed Albert Lasker, a Jewish businessman and Harding's 1920 Presidential campaign manager, head of the Shipping Department. In an unpublished letter, Harding advocated the establishment and funding of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.[97]

Life at the White House

Katherine Marcia Forbes, wife of Harding's Veterans Bureau appointment Charles R. Forbes, had unprecedented access to the White House. Mrs. Harding and Katherine had become close friends since meeting in Hawaii, when Senator Harding and his wife were on vacation. In 1921, Katherine Forbes wrote a series of articles for the Washington Post describing the daily life of President Harding and the First Lady. President Harding and Mrs. Harding wanted to be known as, "...just home folks." At dinners, Harding's dog Laddie Boy, was allowed to beg guests for food and play with children. Red velvet upholstery covered much of the furniture. Harding's informal dress included a plain tuxedo, pleated shirt, and pearl studs. Mrs. Harding herself was able to talk with many guests at the same time. Inside the White House, the Hardings had a great grandfather clock, a gold fish bowl, a French vase with pussy willows, neutral color rugs, and a grand piano. Harding sometimes gave children private tours of the White House that included the conservatories and kennels.[98]

Harding's lifestyle at the White House was fairly unconventional compared to his predecessor President Woodrow Wilson. Upstairs at the White House, in the Yellow Oval Room, Harding allowed bootleg whiskey to be freely served to his guests during after-dinner parties at a time when the President was supposed to enforce Prohibition. One witness, Alice Longworth, daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, stated that trays, "...with bottles containing every imaginable brand of whiskey stood about."[99] Some of this alcohol had been directly confiscated from the Prohibition department by Jess Smith, assistant to U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty. Mrs. Harding, also known as the "Duchess", mixed drinks for the guests.[100] Harding played poker twice a week, smoked and chewed tobacco. Harding allegedly won a $4,000 pearl necktie pin at one White House poker game.[101] Although criticized by Prohibitionist advocate Wayne B. Wheeler over Washington, D.C. rumors of these "wild parties", Harding claimed his personal drinking inside the White House was his own business.[102]

Administrative scandals

Upon winning the election, Harding appointed many of his longtime allies and campaign contributors to prominent political positions in control of vast amounts of government money and resources. Known as the "Ohio Gang" (a term used by Charles Mee Jr., in his book of the same name), some of the appointees used their new powers to exploit their positions for personal gain. Although Harding was responsible for making these appointments, it is unclear how much, if anything, Harding himself knew about his friends' illicit activities. No evidence to date suggests that Harding personally profited from such crimes, but he was apparently unable to prevent them. "I have no trouble with my enemies", Harding told journalist William Allen White late in his presidency, "but my damn friends, they're the ones that keep me walking the floor nights!"[83] The only scandal which was openly discovered during Harding's lifetime was in the Veteran's Bureau.[103] Yet the gossip became rampant after the suicides of Charles Cramer (Veterans Bureau) and Jess Smith (Justice Dept.) Harding responded aggressively to all of this with a mixture of grief, anger and perplexity.

Before any of the scandalous activity became widely known, Harding's popularity began to ebb, but he responded with determination to run for re-election, despite strong support emerging for the very popular Henry Ford for the Democrats.[104] While on his trip to Alaska in 1923, Harding asked reporters and Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, how he should respond to associates who may have betrayed him.[105] He also said at this time, according to Joe Mitchell Chapple, "Someday the people will understand all that some of my erstwhile friends have done for me."[106] However much he did know at the time of his departure for Alaska, Russell concludes it did not include Fall and Daugherty.[107] Harding reformed the corrupt Veteran's Bureau in March, 1923.[108]

Teapot Dome

The most notorious scandal was Teapot Dome, most of which came to light after Harding's death. This affair concerned an oil reserve in Wyoming that was covered by a teapot-shaped rock formation. For years, the country had taken measures to ensure the availability of petroleum reserves, particularly for the Navy's use.[109] On February 23, 1923, Harding issued Executive Order # 3797, which created the Naval Petroleum Reserve Number 4 in Alaska. By the 1920s, it was clear that petroleum was important to the national economy and security. The reserve system was to keep the oil under government jurisdiction rather than subject to private claims.[110] Management of these reserves was the subject of multi-dimensional arguments—beginning with a turf battle between the Secretary of the Navy and the Interior Dept.[111] The strategic reserves issue was also a debate topic between conservationists and the petroleum industry, as well as those who favored public ownership versus private control.[112] Harding's Secretary of the Interior, Albert B. Fall, brought to that office significant political and legal experience, in addition to heavy personal debt, incurred in his obsession to expand his personal estate, Three Rivers, in New Mexico. He also was an avid supporter of the private ownership and management of reserves.[113]

Fall contracted Edward Doheny of Pan American Corp. to build storage tanks in exchange for drilling rights. It later came to light that Doheny had made significant personal loans to Fall.[114] The Secretary also negotiated leases for the Teapot Dome reserves to Harry Sinclair of the Consolidated Oil Corp. in return for guaranteed oil reserves to the credit of the government. Again, it later emerged that Sinclair had personally made concurrent cash payments of over $400,000 to Fall.[113] These activities took place under the watch of progressive and conservationist attorney, Harry A. Slattery, acting for Gifford Pinchot and Robert La Follete.[115] Fall was ultimately convicted in 1931 of accepting bribes and illegal no-interest personal loans in exchange for the leasing of public oil fields to business associates.[116] In 1931, Fall was the first cabinet member in history imprisoned for crimes committed while in office.[117] Paradoxically, while Fall was convicted for taking the bribe, Doheny was acquitted of paying it.[118]

Justice Department

Harding's appointment of Harry M. Daugherty as Attorney General received more criticism than any other. As Harding's campaign manager, Daugherty's Ohio lobbying and back room maneuvers with politicians were not considered the best qualifications.[119] Historian M. R. Werner referred to the Justice Department under Harding and Daugherty as "the den of a ward politician and the White House a night club". On September 16, 1922, Minnesota Congressman Oscar E. Keller brought impeachment charges against Daugherty. On December 4, formal investigation hearings, headed by congressman Andrew J. Volstead, began against Daugherty. The impeachment process, however, stopped, since Keller's charges that Daugherty protected interests in trust and war fraud cases could not be substantially proven.[120]

One alleged scandal involving Daugherty concerned the Wright-Martin Aircraft Corp., which supposedly overcharged the Federal government by $2.3 million on war contracts.[121] Capt. Hazel Scaife tried to bring the company to trial, but was blocked by the Department of Justice. At this time, Daugherty was said to have owned stock in the company and was even adding to these holdings, though he was never charged in the matter.[122]

Daugherty remained in his position during the early days of the Calvin Coolidge administration, then resigned on March 28, 1924, amidst allegations that he accepted bribes from bootleggers. Daugherty was later tried and acquitted twice for corruption. Both juries hung—in one case, after 65 hours of deliberation. Daugherty's famous defense attorney, Max D. Steuer, blamed all corruption allegations against Daugherty on Jess Smith, an aide at the Justice Department who had committed suicide.[123]

Harding's Attorney General hired William J. Burns to run the Justice Dept.'s Bureau of Investigation,[124] Burns was said to be unabashed in his willingness to conduct unauthorized searches and seizures of political enemies of the Justice Dept. A number of inquisitive congressmen or senators found themselves the object of wire taps, rifled files, and copied correspondence.[125] Burns' primary operative was Gaston B. Means, a reputed con man, who was known to have fixed prosecutions, sold favors, and manipulated files in the Justice Dept.[126] Means, who acted independently, took direct instructions and payments from Jess Smith, without Burn's knowledge, to spy on Congressmen. Means hired a woman, Laura Jacobson, to spy on Senator Thaddeus Caraway, a critic of the Harding administration. Means also was involved with "roping" bootleggers.[120]

Narcotic trafficking was rampant at the Atlanta Penitentiary while Daugherty was Attorney General. The appointed warden, J.E. Dyche, made internal prison reforms by firing two guards while two other officers were indicted by the Justice Department. Daugherty, however, was slow to follow up on these indictments. As Dyche began to investigate the drug supply ring outside the prison, Daugherty fired him and replaced him with a close friend, A. E. Sartain. Daugherty stopped the investigation into the drug ring until the two indicted officers were brought to trial. The Superintendent of Prisons, Heber Votaw, allegedly interfered and suppressed Dyche's attempted investigation into the narcotic ring outside the prison. Votaw, was Harding's brother-in-law, and had been appointed by the President in April 1921. Harding sent Charles R. Forbes, Director of the Veterans Bureau, to privately investigate the matter. This upset Daugherty, who said the Atlanta prison situation was none of Forbes' business.[127][128]

Daugherty, according to a 1924 Senate investigation into the Justice Department, had authorized a system of graft between aides Jess Smith and Howard Mannington. Both Mannington and Smith allegedly took bribes to secure appointments, prison pardons, and freedom from prosecution. A majority of these purchasable pardons were directed towards bootleggers. Cincinnati bootlegger, George L. Remus, allegedly paid Jess Smith $250,000 to not prosecute him. Remus, however, was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to Atlanta prison. Smith tried to extract more bribe money from Remus to pay for a pardon. The prevalent question at the Justice Department was "How is he fixed?"[129]

Jess W. Smith

Daugherty's personal aide, Jess W. Smith, was widely viewed as the Attorney General's (and therefore the President's) spokesman and henchman. Smith was considered Daugherty's proxy, and a central figure, in government file manipulation, paroles and pardons, influence peddling—and even served as bag man.[130]

During Prohibition, pharmacies received alcohol permits to sell alcohol for medical purposes. According to Congressional testimony, Daugherty allegedly arranged for Jess Smith and Howard Mannington to sell these permits to drug company agents who really represented bootleggers. The bootleggers, having obtained a permit could buy cases of whiskey. Smith and Mannington split the permit sales profits. Approximately 50,000 to 60,000 cases of whiskey were sold to bootleggers at a net worth of $750,000 to $900,000. Smith supplied bootleg whiskey to the White House and the Ohio Gang house on K Street, concealing the whiskey in a briefcase for poker games.[43][100]

Eventually, rumors of Smith's abuses—free use of government cars, going to all night parties, manipulation of Justice Department files—reached Harding. Harding withdrew Smith's White House clearance and Daugherty told him to leave Washington. On May 30, 1923, Smith's dead body was found at Daugherty's apartment with a gunshot wound to the head. William J. Burns immediately took Smith's body away and there was no autopsy. Historian Francis Russell, concluding this was a suicide, indicates that a Daugherty aide entered Smith's room moments after a noise awoke him, and found Smith on the floor with his head in a trash can and a revolver in his hand. Russell also states that Smith had purchased the gun (though he was said to have detested guns), that a bullet had entered Smith's temple, exited the forehead, and lodged in a doorjamb. Smith allegedly purchased the gun from a hardware store shortly before his death, after Daugherty verbally abused him for waking him up from a nap.[131][132]

Veterans' bureau

Charles R. Forbes, the energetic Director of the Veterans Bureau, disregarded the dire needs of wounded World War I veterans to procure his own wealth.[133] To limit corruption in the Veterans' Bureau, Harding insisted that all government contracts be by public notice, but Forbes provided inside information to his co-conspirators to ensure their bids succeeded.[60] After his appointment, Forbes was quick to have Harding issue executive orders that gave him control over veterans' hospital construction and supplies.[103] Forbes defrauded the government of an estimated $225 million through hospital construction, after increasing construction costs from $3,000 to $4,000 per bed.[134] Forbes' main task at the Veterans bureau, having an unprecedented $500 million yearly budget, was to ensure that new hospitals were built around the country to help the 300,000 wounded World War I veterans.[135]

In the Spring of 1922, Forbes went on tours, known as joy-rides, of new hospital construction sites around the country and the Pacific Coast. On these tours, Forbes allegedly received traveling perks and alcohol kickbacks, took a $5,000 bribe in Chicago, and made a secret code to ensure $17 million in government construction hospital contracts with corrupt contractors. On the tours, Forbes allegedly went to parties, drank bootleg liquor, and played craps.[136]

Intent on making more money, on his return to the U.S. Capitol Forbes immediately began selling valuable hospital supplies under his control in large warehouses at the Perryville Depot.[137] The government had stockpiled huge amounts of hospital supplies during the first World War, which Forbes unloaded for a fraction of their cost to the Boston firm of Thompson and Kelly. In exchange for the deal, J.W. Thompson of the firm added $150,000 to the contract for Forbes, who also received a percentage of the profits realized.[138][139] The check on Forbes' authority at Perryville was Gen. Charles E. Sawyer, chairman of the Federal Hospitalization Board, who represented controlling interests in the valuable hospital supplies.[140]

.jpg)

Dr. Sawyer and Forbes were at odds with each other over authority at the Veterans Bureau.[141] Sawyer, a homeopathic doctor who was Harding's personal physician, told Harding that Forbes was selling valuable hospital supplies to an insider contractor.[142] After issuing two orders for the sales to stop, Harding finally summoned Forbes to the White House and demanded Forbes' resignation, since Forbes had been insubordinate in not stopping the shipments.[143] Harding, however, was not yet ready to announce Forbes' resignation and let him flee to Europe on the "flimsy pretext" that he would help disabled U.S. Veterans in Europe.[144][145] While in Europe, Forbes submitted his resignation to Harding on February 15, 1923.

Harding placed a reformer, Brigadier General Frank T. Hines, in charge of the Veterans Bureau. Hines immediately cleared up the mess left by Forbes. When Forbes returned to the U.S., he visited Harding at the White House in the Red Room. During the meeting, Harding angrily grabbed Forbes by the throat, shook him vigorously, and exclaimed "You double-crossing bastard!"[146] A guest who had an appointment with the President interrupted this physical encounter and Forbes was allowed to leave. Harding was bitter over Forbes' "betrayal" and the two never saw each other again.[147] In 1926, Forbes was brought to trial and convicted of conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government. He received a two-year prison sentence and was released in November 1927.[148]

Charles F. Cramer, Forbes' legal council to the Veterans Bureau, rocked the nation's capital when he committed suicide in 1923.[149][150] Cramer was found dead by a maid in his bathroom on the morning of March 14 with a bullet wound to the head. Previously, in the fall of 1922 Cramer had been "bitterly assailed" by the American Legion at Indianapolis over alleged corruption at the Veterans Bureau. Cramer, at the time of his death, was being investigated by a Senate committee and had been criticized and personally attacked. Cramer, himself, had denied charges of corruption and said he had given his "whole-hearted and patriotic service" to the Bureau. Cramer had paid $40,000 in Veteran funds to a private landholder to lease land to build a Veterans Hospital in Camp Kearny, California. The estimated value of the 325-acre land tract was only $8,000. Maj. Gen. John F. O'Ryan conducted the investigation into the Veterans' Bureau. In addition to replacing Forbes with Hines, Harding dismissed or transferred a number of subordinates at the Veteran's Bureau.[151][152]

Shipping board, office of alien property and prohibition bureau

On June 13, 1921, Harding appointed Albert D. Lasker chairman of the United States Shipping Board. Lasker, a cash donor and Harding's general campaign manager, had no previous experience with shipping companies. The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 had allowed the Shipping Board to sell ships made by the U.S. Government to private American companies. A congressional investigation revealed that while Lasker was in charge, many valuable steel cargo ships, worth between $200 and $250 a ton, were sold for as low as $30 a ton to private American shipping companies without an appraisal board. J. Harry Philbin, a manager in the sales division, testified at the congressional hearing that under Lasker's authority U.S. ships were sold, "...as is, where is, take your pick, no matter which vessel you took." Lasker resigned from the Shipping Board on July 1, 1923.[153]

Thomas W. Miller, head of the Office of Alien Property, was convicted of accepting bribes. Miller's citizenship rights were taken away and he was sentenced to 18 months in prison and a $5,000 fine. After Miller served 13 months of his sentence, he was released on parole. President Herbert Hoover restored Miller's citizenship on February 2, 1933.[154]

Roy Asa Haynes, Harding's Prohibition Commissioner, ran the patronage-riddled Prohibition bureau, which was allegedly corrupt from top to bottom.[155] The bureau's "B permits" for liquor sales became tantamount to negotiable securities, as a result of being so widely bought and sold among known violators of the law.[156] The bureau's agents allegedly made a year's salary from one month's illicit sales of permits.[155]

Western travels, illness and death

In June 1923, Harding set out on a westward cross-country Voyage of Understanding, in which he planned to renew his connection with the people, away from the capital, and explain his policies. The schedule included 18 speeches and innumerable informal talks. Accompanying him were Secretaries Work, Wallace, and Hoover, House Speaker Gillett, and Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman.[157] During this trip, he became the first president to visit Alaska.[158]

Harding's physical health had declined since the fall of 1922. One doctor, Emmanuel Libman, who met Harding at a dinner, privately suggested that the President was suffering from coronary disease. By early 1923, Harding had trouble sleeping, looked tired, and could barely get through nine holes of golf.

Though Harding wanted to run for a second term, he may have been aware of his own health decline. He gave up drinking, sold his "life-work," the Marion Star, in part to regain $170,000 previous investment losses, and had the U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty make a new will. Harding, along with his personal physician Dr. Charles E. Sawyer, believed getting away from Washington would help relieve the stress of being President. By July 1923, criticism of the Harding Administration was increasing. Prior to his leaving Washington, the President reported chest pains that radiated down his left arm.[159][160]

St. Louis, Kansas, Denver

During Harding's western travels, historian Samuel H. Adams claims that Harding's political views began to expand, and became more independent from established Republican Party agenda. In St. Louis, Harding promoted U.S. participation in the World Court having earnestly desired world peace. In Kansas, Harding gave a speech on agriculture and, much to his doctor's displeasure, rode on a farming combine in searing summer heat.

In Denver, Harding extolled the virtues of the 18th Amendment, saying it should never be repealed, urging that the prohibition laws be obeyed.[161][162] Harding, himself, did not pack any whiskey for traveling on the Presidential train. Breaking away from Republican isolationism, Harding advocated more spending on national defense in case of another war. Harding also made a speech fully endorsing labor's right to organize, and even spoke against those who sought to destroy labor movements around the country. In Tacoma, Washington, the President read a letter that promoted his efforts for a 12-hour work day. Sensing his own conversion, Harding even told his friends that he felt a spiritual change was influencing his stance on issues.[162]

Alaska trip

President Harding, as his physically demanding schedule continued, boarded a naval transport ship, the USS Henderson, and voyaged to Alaska. During four days at sea, Harding was unable to rest and regain strength.[163] Rumors of corruption in his administration were beginning to circulate in Washington. While in Alaska, Harding was profoundly shocked by a long message he received detailing illegal activities previously unknown to him.[164]

Harding came to the most northern U.S. territory to "open up Alaska lands" for oil, mining, timber development, and industry.[165] He also wanted to encourage settlers to move to the sparsely populated territory. Harding hoped that, with completion of the Alaska Railroad, World War I veterans from Alaska would return to their home territory, and impoverished workers in the lower states could go to Alaska for employment. Harding brought along the secretaries of the Interior, Commerce, and Agriculture to cut through bureaucracy in their respective departmental jurisdictions.[166]

Harding arrived in Alaska on the Henderson on July 7, 1923. Harding and his presidential party first visited Metlakatla, Ketchikan (July 8), and Wrangell (July 9). They continued on to Juneau (July 10), Skagway, and Glacier Bay (July 11).[167] The President then cruised to Seward (July 13). They then proceeded to travel by Presidential railway car and automobile. Harding visited Snow River on the Kenai Peninsula, Anchorage (July 13), Chickaloon, Wasilla and Willow (July 14). The U.S. government had bought up the financially unstable Tanana Valley Railroad. The President continued his Alaska journey through Montana Station, Curry (July 14) Cantwell, McKinley Park and Nenana (July 15).[168] On July 15, Harding drove in the golden spike on the north side of the steel Mears Memorial Bridge that completed the Alaska Railroad.[167] The trip continued to Fairbanks (July 15). He went to Seward (July 18), Valdez (July 19), Cordova (July 20), and Sitka (July 22).

The information gathered by Harding's Alaska tour found that improving agriculture in south central Alaska would require irrigation because of the low rainfall totals. By 1923, the Alaskan salmon population was being depleted from overfishing. Harvesting and transporting coal by ship from Alaska through the territory's panhandle would be very expensive.[166]

After leaving Alaska, Harding stopped in Vancouver, British Columbia.[169] In doing so, he became the first U.S. president to visit Canada while in office.[170] After an official reception and tour of the city,[171] Harding became exhausted while playing golf and complained of nausea and upper abdominal pain. His doctor, Charles E. Sawyer, believed Harding's illness was a severe case of food poisoning. Nevertheless, Dr. Joel T. Boone also examined the President and noticed an enlargement of his heart.[164] He was given digitalis. Nevertheless, Harding met with British Columbia Premier John Oliver and Mayor of Vancouver Charles Tisdall and spoke in front of 50,000 people with his voice projected by microphones.

Next, it was onto Seattle, Washington, where Harding kept to a busy schedule, giving a speech to 25,000 people at the University of Washington stadium in Seattle. Harding spoke on the magnificence of Alaska's wilderness, conservationism, and "measureless oil resources in the most northerly sections." Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover wrote the Seattle speech and Harding claimed he would protect the territory from looters and profit seekers; a rebuff to former Secretary of Interior Albert Fall.[172] Harding had rushed through his speech, and departed quickly, not waiting for audience's applause. It would be the president's last public address.[173] He then traveled by train to Portland, Oregon. A scheduled speech there was canceled.

Death in San Francisco, state funeral and memorial

The President's train continued south to San Francisco. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover sent a telegram from Dunsmuir, California, to his friend Dr. Ray L. Wilbur, asking Wilbur to meet and to personally evaluate the President. Arriving at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, Harding developed a respiratory illness believed to be pneumonia.[160][174][175] Harding, severely exhausted, ordered that his planned speech be issued through the national press in order to communicate with the public. The President was given digitalis and caffeine that momentarily helped relieve his heart condition and sleeplessness.[160][175] On Thursday, the President's health appeared to improve, so his doctors went to dinner. Harding's pulse was normal and his lung infection had subsided.[176] Unexpectedly, during the evening, Harding shuddered and died suddenly in the middle of conversation with his wife in the hotel's presidential suite, at 7:35 p.m. on August 2, 1923.[174][176] Dr. Sawyer (a homeopath, and friend of the Harding family), opined that Harding had succumbed to a stroke, but doctors there disagreed.[174] The doctors issued a release stating that the cause of death was "some brain evolvement, probably an apoplexy."[177] Mrs. Harding refused to allow an autopsy.[174][178] In retrospect, scholars speculate that Harding had shown physical signs of cardiac insufficiency with congestive heart failure in the preceding weeks.[179][180] Navy doctors who examined the president in San Francisco concluded he had suffered a heart attack. Dr. Wilbur included in his memoirs a letter from Dr. Charles Miner Cooper in support of their cerebral apoplexy diagnosis, based on Harding's last observed condition, while acknowledging that no final determination could be made.[181] Harding was succeeded as President by Calvin Coolidge.

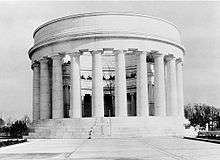

The funeral train made a four-day journey eastward across the country—the first such procession since Lincoln's funeral train. Millions lined the tracks in cities and towns across the country to pay their respects.[182] Harding's casket was placed in the East Room of the White House pending a state funeral, which was held on August 8, 1923, at the United States Capitol. Harding's death was widely mourned by the nation and the average citizen felt a "personal loss."[183] Harding was entombed in the receiving vault of the Marion Cemetery, on August 10, 1923. After her own death on November 21, 1924, Mrs. Harding was interred next to her husband. Their remains were re-interred December 20, 1927, at the newly completed Harding Memorial in Marion, Ohio. Harding was one of only two presidents to be survived by his father, the other being John F. Kennedy.

Speculation on cause of death

Harding's sudden death led to theories that he had been poisoned[178] or committed suicide. Suicide appears unlikely, since Harding was planning to run for reelection in 1924. Rumors of poisoning were fueled, in part, by a book called The Strange Death of President Harding, in which the author, a convicted criminal, Gaston Means, suggested Mrs. Harding had poisoned her husband, an assertion which has since been completely discredited as false.

Mrs. Harding's refusal to allow an autopsy added to such speculation. According to the physicians attending Harding, however, the symptoms prior to his death all pointed to congestive heart failure. Harding's biographer, Samuel H. Adams, concluded that "Warren G. Harding died a natural death which, in any case, could not have been long postponed".[184]

Disposition of Presidential papers

Immediately after Harding's death, Mrs. Harding returned to Washington, D.C., and stayed in the White House briefly with the Coolidges. In 1963 Francis Russell, writing in American Heritage, stated that former First Lady Harding gathered and burned as much of President Harding's correspondence and documents, both official and unofficial, as she could get. Russell also wrote that Mrs. Harding hired secretaries upon returning to Marion, to help her collect Harding's personal correspondence to others and that Mrs. Harding then in turn destroyed these letters.[185]

However, John Dean, in Warren G. Harding:The American Presidents Series, states that Mrs. Harding's efforts were in vain and that George Christian, President Harding's private secretary, disobeyed Florence Harding's instructions, only sending a few boxes of materials to her in Marion after she left the White House. The papers were instead stored in the White House's basement and not found until 1929. Christian also kept all of the papers from Harding's time in the Senate, along with records of Harding's Presidential campaign, and stored them in the basement of his own home in Marion.

By 1935, according to Dean, the Presidential papers were all under the purview of the Harding Memorial Association which in late 1963 transferred the papers to the Ohio Historical Society and that the substantial collection was opened to the public in April 1964. The papers were subsequently microfilmed in the 1970s and can be accessed at various libraries.[186]

Cabinet

| The Harding Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Warren G. Harding | 1921–1923 |

| Vice President | Calvin Coolidge | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of State | Charles Evans Hughes | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Andrew Mellon | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of War | John W. Weeks | 1921–1923 |

| Attorney General | Harry M. Daugherty | 1921–1923 |

| Postmaster General | Will H. Hays | 1921–1922 |

| Hubert Work | 1922–1923 | |

| Harry S. New | 1923 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Edwin Denby | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Albert B. Fall | 1921–1923 |

| Hubert Work | 1923 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Henry C. Wallace | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Commerce | Herbert Hoover | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Labor | James J. Davis | 1921–1923 |

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

Harding appointed the following justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- William Howard Taft—Chief Justice: 1921

- George Sutherland: 1922

- Pierce Butler: 1923

- Edward Terry Sanford: 1923

Other judicial appointments

Harding also appointed 6 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, 42 judges to the United States district courts, and 2 judges to the United States Court of Customs Appeals.

Extramarital affairs

In a 1998 Washington Post article, journalist Carl S. Anthony wrote that Harding had extramarital affairs and sexual encounters with numerous women.[187] These women included Susie Hodder and Carrie Fulton Phillips, Mrs. Harding's personal friends; Grace Cross, Harding's senatorial aide; and Nan Britton, a 22-year-old campaign volunteer (President Harding was age 51 when the affair occurred). Anthony stated that Harding was the father of Hodder's daughter.[187] In her 1927 book, The President's Daughter, Britton said that Harding fathered her daughter, Elizabeth Ann, as well, during a 1919 tryst in his senatorial offices. Britton, who had a profound obsession with Harding beginning in high school, also said that she was his mistress before and during his administration – reportedly, this included at least one infamous tryst in a White House closet and while guarded by United States Secret Service agents.[187][188] Historian Henry F. Graff states that Harding was sterile and that Harding's affair with Britton ended after Harding assumed the presidency.[189] The Library of Congress publicly opened letters between Phillips and Harding on July 29, 2014.[190][191]

Historian Francis Russell wrote that, beginning in the spring of 1905, Harding had a 15-year relationship with Carrie Fulton Phillips, wife of businessman and friend James Eaton Phillips of Marion, Ohio.[192] More than 100 intimate letters between Harding and Mrs. Philips were discovered in the 1960s, but publication of the letters was enjoined by court order in Ohio until 2024.[189] Russell, however, viewed the letters upon their discovery and described them as very touching and naive in some respects, erotic in others.[193] Russell concluded from the letters that Phillips was the love of Harding's life — "the enticements of his mind and body combined in one person".[192]

Before his death, Harding had established a margin account with stockbroker Sam Ungerleider. Before the broker could get authority from Harding's successors to liquidate the stocks purchased on loan, the account had a loss of more than $170,000. The broker was given the authority to sell, but the family refused to settle the loss and the broker declined to force collection.[194]

The most sensational allegations include one that Harding and Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty participated in bacchanalian orgies at the Ohio Gang's Little Green House on K Street in Washington, D.C.; witnesses to this were considered unreliable and one was a convicted perjurer.[189] Also, in his 1987 book The Fiery Cross, historian Wyn Craig Wade suggested that Harding had ties with the Ku Klux Klan, perhaps having been inducted into the organization in a private White House ceremony. Evidence included the taped testimony of one of the members of the alleged induction team; however, evidence beyond that is scanty. Other historians generally dismiss these stories.[195] Several historians, including Robert H. Ferrell and Paul Johnson, reject claims of orgies and mistresses. Johnson writes in Modern Times: "When in 1964 the Harding Papers (which had not been burnt) were opened to scholars, no truth at all was found in any of the myths, though it emerged that Harding, a pathetically shy man with women, had a sad and touching friendship with the wife of a Marion store-owner before his presidency. The Babylonian image was a fantasy, and in all essentials Harding had been an honest and exceptionally shrewd president."[196]

Historical ranking as president

Harding has been traditionally ranked as one of the worst presidents. In a 1948 poll conducted by Harvard University historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr., the first notable survey of scholars' opinions of the presidents, Harding ranked last among the 29 presidents considered. In a 1962 poll conducted by Schlesinger, he was ranked last again, 31 out of 31. His son, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., conducted another poll in 1996; once again, Harding was last, ranked 39 out of 39. In 2010, a Siena College Research Institute survey of 238 presidential scholars ranked Harding 41st among the 43 men who had been president, between Franklin Pierce (40th) and James Buchanan (42nd); Andrew Johnson was judged the worst.[197] Harding was also considered the third worst president in a 2002 Siena poll. Siena polls of 1982, 1990 and 1992 ranked him last.

However, Harding's biographer John W. Dean in 2004 believed that Harding was underrated.[198] Authors Marcus Raskin and Robert Spero, in 2007, also believed that Harding was underrated, and admired Harding's quest for world peace after World War I and his successful naval disarmament among strongly armed nations, including France, Britain, and Japan.[199] In his 2010 book The Leaders We Deserved (and a Few We Didn't): Rethinking the Presidential Rating Game, presidential historian Alvin S. Felzenberg, ranking presidents on several criteria, ranked Harding 26th out of 40 presidents considered.[200]

Life legacy

As a career politician, Harding exhibited an ability to grow, and had a desire to get along with political enemies rather than alienate them. As a prior journalist, Harding was the first President to realize the importance of an ever-growing powerful media, and even ordered his cabinet to organize their own respective press staff. He knew that radio would eventually dominate American commerce and promoted two Radio Conferences to give government power to regulate the industry. Harding also sensed the importance of oil in terms of national security and prosperity, signing an executive order that gave the U.S. a giant oil reserve in Alaska. He also signed America's first child welfare program designed to protect children's health and ensure that they would grow up without neglect from their parents.

Harding's generosity and loyalty to friends was a liability as President. Multiple scandals evolved during his administration that damaged his reputation throughout the nation. His successes as President were overshadowed by the "Ohio Gang" criminal exploits, the detrimental image of his social drinking, and his alleged extramarital affairs. His sudden death in 1923 only intensified unanswered questions concerning his knowledge of, and potential involvement in, the scandals—and if he would have reformed his administration. His reputation was so controversial that not until 1931 was Harding's marble memorial colonnade in Marion dedicated by Herbert Hoover. According to Hoover, Harding's legacy was one of tragic betrayal.[203]

Harding's legacy began to improve during the 1970s, however. The truth behind the many presidential scandals and his personal controversies may never be known. To protect her husband's damaged legacy, Mrs. Harding only left 1/7 of Harding's personal papers for posterity. She destroyed the rest.[204] The remaining papers, except for Harding's speeches, are currently unpublished. Harding has been one of the most historically challenging American Presidents in terms of finding private letters and paper documents.[205][206] Historian Hazel Rowley writes that because the Harding administration and the Republicans were seen associated with prosperity, prominent Democrats were reluctant to run for president in 1924.[207]

Because of his untimely demise, Warren G. Harding is among the relatively few American Presidents who have been honored on a U.S. postage stamp more than the usual three times. Harding has appeared on US postage for a total of five issues, more than that of most Presidents.[201][202] Harding's election provided a short burst of popularity for the name Warren.[208]

Memorials

- Warren G. Harding High School, Warren, Ohio

- Warren G. Harding Middle School, Steubenville, Ohio

- Warren G. Harding High School; Bridgeport, Connecticut

- Warren G. Harding Middle School, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Harding Senior High School, Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Harding Middle School, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

- Harding Elementary School, Santa Barbara, California