Records of the Grand Historian

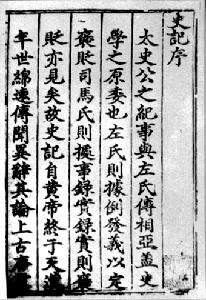

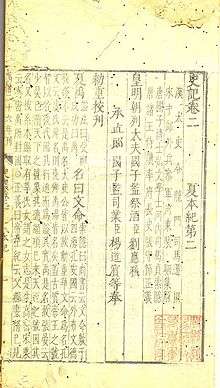

Early printed edition | |

| Author | Sima Qian |

|---|---|

| Original title |

太史公書 (Tàishǐgōng shū) 史記 (Shǐjì) |

| Country | Han China |

| Language | Classical Chinese |

| Subject | Ancient Chinese history |

| Records of the Grand Historian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Shiji" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 史記 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 史记 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "The Scribe's Records" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 太史公書 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太史公书 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Records of the Grand Historian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Records of the Grand Historian (太史公書), now usually known as the Shǐjì (史記, "The Scribe's Records"), is a monumental history of ancient China and the world finished around 94 BC by the Han dynasty official Sima Qian after having been started by his father, Sima Tan, Grand Astrologer to the imperial court. The work covers the world as it was then known to the Chinese and a 2500-year period from the age of the legendary Yellow Emperor to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han in the author's own time.[1]

The Records has been called a "foundational text in Chinese civilization".[2] After Confucius and the First Emperor of Qin, "Sima Qian was one of the creators of Imperial China, not least because by providing definitive biographies, he virtually created the two earlier figures."[3] The Records set the model for the 24 subsequent dynastic histories of China. Unlike Western historical works, the Records do not treat history as "a continuous, sweeping narrative", but rather break it up into smaller, overlapping units dealing with famous leaders, individuals, and major topics of significance.[4]

History

The work that became Records of the Grand Historian was begun by Sima Tan, the Grand Astrologer (Tai shi 太史) of the Han dynasty court during the late 2nd century BC. After his death in 110 BC, it was continued and completed by his son and successor Sima Qian, who is generally credited as the work's author.[5][6] Sima Qian is known to have completed the Records before his death in c. 86 BC, with one copy residing in the imperial capital of Chang'an (modern Xi'an) and the other copy probably being stored in his home.[7]

Details regarding the Records' early reception and circulation are not well known.[8] A number of 1st century BC authors, such as the scholar Chu Shaosun (褚少孫; fl. 32–7 BC), added interpolations to the Records, and may have had to reconstruct portions of it: ten of the original 130 chapters were lost in the Eastern Han period (AD 25–220) and seem to have been reconstructed later.[7]

Beginning in the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589) and the Tang dynasty (607–918), a number of scholars wrote and edited commentaries to the Records.[7] Most 1st millennium editions of the Records include the commentaries of Pei Yin (裴駰, 5th century), Sima Zhen (司馬貞, early 8th century), and Zhang Shoujie (張守節, early 8th century).[9][10] The primary modern edition of the Records, which is punctuated and does not include commentaries, is the Zhonghua Book Company edition of 1959 (revised in 1985), and is based on an edition prepared by the Chinese historian Gu Jiegang in the early 1930s.[11]

Manuscripts

There are two known surviving fragments of Records manuscripts from before the Tang dynasty, both of which are preserved in the Ishiyama-dera temple in Ōtsu, Japan. Portions of at least nine Tang dynasty manuscripts survive: three fragments discovered among the Dunhuang manuscripts in the early 20th century, and six manuscripts preserved in Japanese temples and museums, such as the Kōzan-ji temple in Kyoto and the Tōyō Bunko museum in Tokyo. A number of woodblock printed editions of the Records survive, the earliest of which date to the Song dynasty (960–1297).[9]

Contents

In all, the Records is about 526,000 Chinese characters long, making it four times longer than Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War and longer than the Old Testament.[12][13]

Sima Qian conceived and composed his work in self-contained units, with a good deal of repetition between them. His manuscript was written on bamboo slips with about 24 to 36 characters each, and assembled into bundles of around 30 slips. Even after the manuscript was allowed to circulate or be copied, the work would have circulated as bundles of bamboo slips or small groups. Endymion Wilkinson calculates that there were probably between 466 and 700 bundles, whose total weight would have been 88–132 pounds (40–60 kg), which would have been difficult to access and hard to transport. Later copies on silk would have been much lighter, but also expensive and rare. Until the work was transferred to paper many centuries later, circulation would have been difficult and piecemeal, which accounts for many of the errors and variations in the text.[13]

Sima Qian organized the chapters of Records of the Grand Historian into five categories, which each comprise a section of the book.

- Basic Annals (běnjì 本紀)

- The "Basic Annals" make up the first 12 chapters of the Records, and are largely similar to records from the ancient Chinese court chronicle tradition, such as the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu 春秋).[14] The first five cover either periods, such as the Five Emperors, or individual dynasties, such as the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties.[14] The last seven cover individual rulers, starting with the First Emperor of Qin and progressing through the first emperors of the Han dynasty.[14] In this section, Sima chose to also include de facto rulers of China, such as Xiang Yu and Empress Dowager Lü, while excluding rulers who never held any real power, such as Emperor Yi of Chu and Emperor Hui of Han.[15]

- Tables (biǎo 表)

- Chapters 13 to 22 are the "Tables", which are one genealogical table and nine other chronological tables.[14] They show reigns, important events, and royal lineages in table form, which Sima Qian stated that he did because "the chronologies are difficult to follow when different genealogical lines exist at the same time."[16] Each table except the last one begins with an introduction to the period it covers.[14]

- Treatises (shū 書)

- The "Treatises" (sometimes called "Monographs") is the shortest of the five Records sections, and contains eight chapters (23–30) on the historical evolution of ritual, music, pitch pipes, the calendar, astronomy, sacrifices, rivers and waterways, and financial administration.[14]

- Hereditary Houses (shìjiā 世家)

- The "Hereditary Houses" is the second largest of the five Records sections, and comprises chapters 31 to 60. Within this section, the earlier chapters are very different in nature than the later chapters.[14] Many of the earlier chapters are chronicle-like accounts of the leading states of the Zhou dynasty, such as the states of Qin and Lu, and two of the chapters go back as far as the Shang dynasty.[14] The later chapters, which cover the Han dynasty, contain biographies.[14]

- Ranked Biographies (lièzhuàn 列傳)

- The "Ranked Biographies" (usually shortened to "Biographies") is the largest of the five Records sections, covering chapters 61 to 130, and accounts for 42% of the entire work.[14] The 69 "Biographies" chapters mostly contain biographical profiles of about 130 outstanding ancient Chinese men, ranging from the moral paragon Boyi from the end of the Shang dynasty to some of Sima Qian's near contemporaries.[14] About 40 of the chapters are dedicated to one particular man, but some are about two related figures, while others cover small groups of figures who shared certain roles, such as assassins, caring officials, or Confucian scholars.[14] Unlike most modern biographies, the accounts in the "Biographies" give profiles using anecdotes to depict morals and character, with "unforgettably lively impressions of people of many different kinds and of the age in which they lived."[14] The "Biographies" have been popular throughout Chinese history, and have provided a large number of set phrases still used in modern Chinese.[14]

Style

.jpg)

Unlike subsequent official historical texts that adopted Confucian doctrine, proclaimed the divine rights of the emperors, and degraded any failed claimant to the throne, Sima Qian's more liberal and objective prose has been renowned and followed by poets and novelists. Most volumes of Liezhuan are vivid descriptions of events and persons. The author explains that he critically used stories passed on from antiquity as part of his sources, balancing reliability and accuracy of the records. For instance, the material on Jing Ke's attempt at assassinating the King of Qin was supposedly an eye-witness account passed on by the great-grandfather of a friend of Jing Ke's father, who served as a low-ranking bureaucrat at court of Qin and happened to be attending the diplomatic ceremony for Jing Ke.

It has been observed that the diplomatic Sima Qian has a way of accentuating the positive in his treatment of rulers in the Basic Annals, but slipping negative information into other chapters, and so his work must be read as a whole to obtain full information. For example, the information that Liu Bang (later Emperor Gaozu of Han), in a desperate attempt to escape in a chase from Xiang Yu's men, pushed his own children off his carriage to lighten it, was not given in the emperor's biography, but in the biography of Xiang Yu. He is also careful to balance the negative with the positive, for example, in the biography of Empress Dowager Lu which contains lurid accounts of her cruelty, he pointed out at the end that, whatever her personal life may have been, her rule brought peace and prosperity to the country.[17]

Source materials

Sima's family were hereditary historians to the Han emperor. Sima Qian's father Sima Tan served as Grand Historian, and Sima Qian succeeded to his position. Thus he had access to the early Han dynasty archives, edicts, and records. Sima Qian was a methodical, skeptical historian who had access to ancient books, written on bamboo and wooden slips, from before the time of the Han dynasty. Many of the sources he used did not survive. He not only used archives and imperial records, but also interviewed people and traveled around China to verify information. In his first chapter, "Annals of the Five Emperors," he writes,[18]

I myself have travelled west as far as K'ung-t'ung, north past Cho-lu, east to the sea, and in the south I have sailed the Yellow and Huai Rivers. The elders and old men of these various lands frequently pointed out to me the places where the Yellow Emperor, Yao, and Shun had lived, and in these places the manners and customs seemed quite different. In general those of their accounts which do not differ from the ancient texts seem to be near to the truth.

The Grand Historian used The Annals of the Five Emperors (五帝系諜) and the Classic of History as source materials to make genealogies from the time of the Yellow Emperor until that of the Gonghe regency (841-28 BC). Sima Qian often cites his sources. For example, in the first chapter, "Annals of the Five Emperors", he writes, "I have read the Spring and Autumn Annals and the Guoyu." In his 13th chapter, "Genealogical Table of the Three Ages," Sima Qian writes, "I have read all the genealogies of the kings (dieji 谍记) that exist since the time of the Yellow Emperor." In his 14th chapter, "Yearly Chronicle of the Feudal Lords", he writes, "I have read all the royal annals (chunqiu li pudie 春秋曆譜諜) up until the time of King Li of Zhou." In his 15th chapter, "Yearly Chronicle of the Six States," he writes, “I have read the Annals of Qin (qin ji 秦記), and they say that the Quanrong [a barbarian tribe] defeated King You of Zhou [ca 771 BC]."

In the 19th chapter, he writes, "I have occasion to read over the records of enfeoffment and come to the case of Wu Qian, the marquis of Bian...." (The father of Marquis Bian, Wu Rui, was named king (wang) of Changsha in Hunan for his loyalty to Gaozu. See article on Zhao Tuo). In his chapter on the patriotic minister and poet Qu Yuan, Sima Qian writes, "I have read [Qu Yuan's works] Li Sao, Tianwen ("Heaven Asking"), Zhaohun (summoning the soul), and Ai Ying (Lament for Ying)". In the 62nd chapter, "Biography of Guan and of Yan", he writes, "I have read Guan's Mu Min (牧民 - "Government of the People", a chapter in the Guanzi), Shan Gao ("The Mountains Are High"), Chengma (chariot and horses; a long section on war and economics), Qingzhong (Light and Heavy; i.e. "what is important"), and Jiufu (Nine Houses), as well as the Spring and Autumn Annals of Yanzi." In his 64th chapter, "Biography of Sima Rangju", the Grand Historian writes, "I have read Sima's Art of War." In the 121st chapter, "Biographies of Scholars", he writes, "I read the Imperial Decrees that encouraged education officials."

Sima Qian wrote of the problems with incomplete, fragmentary and contradictory sources. For example, he mentioned in the preface to chapter 15 that the chronicle records of the feudal states kept in the Zhou dynasty's archive were burnt by Qin Shi Huang because they contained criticisms and ridicule of the Qin dynasty, and that the Qin annals were brief and incomplete.[20] In the 13th chapter he mentioned that the chronologies and genealogies of different ancient texts "disagree and contradict each other throughout". In his 18th chapter, Sima Qian writes, "I have set down only what is certain, and in doubtful cases left a blank."[21]

Reliability and accuracy

Scholars have questioned the historicity of legendary kings of the ancient periods given by Sima Qian. Sima Qian began the Shiji with an account of the five rulers of supreme virtue, the Five Emperors who modern scholars, such as those from the Doubting Antiquity School, believe to be originally local deities of the peoples of ancient China.[22] Sima Qian sifted out the elements of the supernatural and fantastic which seemed to contradict their existence as actual human monarchs, and was therefore criticized for turning myths and folklore into sober history.[22]

However, according to Joseph Needham, who wrote in 1954 on Sima Qian accounts of the kings of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–c. 1050 BC):

It was commonly maintained that Ssuma Chhien [Sima Qian] could not have adequate historical materials for his account of what had happened more than a thousand years earlier. One may judge of the astonishment of many, therefore, when it appeared that no less than twenty-three of the thirty rulers' name were to be clearly found on the indisputably genuine Anyang bones. It must be, therefore, that Ssuma Chhien [Sima Qian] did have fairly reliable materials at his disposal—a fact which underlines once more the deep historical-mindedness of the Chinese—and that the Shang dynasty is perfectly acceptable.— Joseph Needham[23]

While some aspects of Sima Qian's history of the Shang dynasty are supported by inscriptions on the oracle bones, there is, as yet, no clear corroborating evidence from archaeology on Sima Qian's history of the Xia dynasty.

There are also discrepancies of fact such as dates between various portions of the work. This may be a result of Sima Qian's use of different source texts.[24]

Transmission and supplementation by other writers

After the completion of the Shiji in ca. 91 BC, the nearly completed manuscript was hidden in the residence of the daughter of Sima Qian, Sima Ying (司馬英), to avoid destruction under Emperor Wu and his immediate successor Emperor Zhao. The Shiji was finally disseminated during the reign of Emperor Xuan by Sima Qian's grandson (through his daughter), Yang Yun (杨惲), after a hiatus of around twenty years.

The changes in the manuscript of the Shiji during this hiatus have always been disputed among scholars. That the text was more or less complete by ca. 91 BC is established in the Letter to Ren'an, and Sima Qian himself gave the precise number of chapters for each section of his work in the postface to Shiji.[25] After his death (presumably only a few years later), few people had the opportunity to see the whole work. However, various additions were still made to it. The historian Liu Zhiji (劉知幾, 661-721) reported the names of a total of fifteen scholars supposed to have added material to the Shiji during the period after the death of Sima Qian. Only the additions by Chu Shaosun (褚少孫, c.105 - c.30 BC) are clearly indicated by adding "Mr Chu said," (Chu xiansheng yue, 褚先生曰). Already in the first century AD, Ban Biao and Ban Gu claimed that ten chapters in Records of the Grand Historian were lacking. A large number of chapters dealing with the first century of the Han dynasty (i.e. the 2nd century BC) correspond exactly to the relevant chapters from the Book of Han (Hanshu). It is unclear whether those chapters initially came from the Shiji or from the Hanshu. Researchers Yves Hervouet (1921-1999) and A.F.P. Hulsewé argued that the originals of those chapters of the Shiji were lost and they were later reconstructed using the corresponding chapters from the Hanshu.[26]

Editions

The earliest extant copy of Records of the Grand Historian, handwritten, was made during the Southern and Northern Dynasties period (420 – 589 AD). The earliest printed edition, called Shiji jijie (史記集解, literally Records of the Grand Historian, Collected Annotations), was published during the Northern Song dynasty. Huang Shanfu's edition, printed under the Southern Song dynasty, is the earliest collection of the Sanjiazhu commentaries on Records of the Grand Historian (三家注, literally: The Combined Annotations of the Three Experts).

In modern times, the Zhonghua Book Company (simp. 中华书局 trad. 中華書局) in Beijing has published the book in both simplified Chinese and traditional Chinese editions. The 1959 (2nd ed., 1982) Sanjiazhu edition (based upon the Jinling Publishing House edition, vide infra) contains commentaries interspersed among the main text and is considered to be an authoritative modern edition.

The most well known editions of the Shiji are:

| Year | Publisher | Printing technique | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279) | Huang Shanfu | Block-printed | Abbreviated as the Huang Shanfu edition (黄善夫本) |

| Ming dynasty, between the times of the Jiajing and Wanli Emperors (between 1521 and 1620) | The Northern and Southern Imperial Academy | Block-printed | published in 21 Shi. Abbreviated as the Jian edition (监本) |

| Ming dynasty | Publisher: the bibliophile Mao Jin (毛晋), 1599 – 1659) and his studio Ji Gu Ge (汲古閣 or the Drawing from Ancient Times Studio) | Block-printed | Published in 17 Shi. Abbreviated as the Mao Ke edition (毛刻本) or the Ji Gu Ge edition (汲古閣本) |

| Qing dynasty, in the time of the Qianlong Emperor (1711 – 1799) | Wu Yingdian | Block-printed | Published in the Twenty-Four Histories, abbreviated as the Wu Yingdian edition (武英殿本) |

| Qing dynasty, in the time of the Tongzhi Emperor (1856 – 1875) | Jinling Publishing House (in Nanjing) | Block-printed | Proofreading and copy editing done by Zhang Wenhu. Published with the Sanjiazhu commentaries, 130 volumes in total. Abbreviated as the Jinling Ju or Jinling Publishing edition (金陵局本) |

Notable translations

English

- Watson, Burton, trans. (1961). Records of the Grand Historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Second edition, 1993 (Records of the Grand Historian). Translates roughly 90 out of 130 chapters.

- Qin dynasty, Volume 1, ISBN 978-0-231-08169-6.

- Qin dynasty, Volume 3, ISBN 978-0-231-08168-9.

- Han dynasty, Volume 1, ISBN 978-0-231-08165-8.

- Second edition, 1993 (Records of the Grand Historian). Translates roughly 90 out of 130 chapters.

- Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang (1974), Records of the Historians. Hong Kong: Commercial Press.

- Reprinted by University Press of the Pacific, 2002. Contains biographies of Confucius and Laozi. ISBN 978-0835106184

- Raymond Stanley Dawson (1994). Historical records. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reprinted, 2007 (The first emperor : selections from the Historical records). Translates only Qin-related material. ISBN 9780199574391

- Nienhauser, William J., ed. (1994– ). The Grand Scribe's Records, 9 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Ongoing, and being translated out of order.

- I. The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China (1994), ISBN 978-0-253-34021-4.

- VI. The Hereditary Houses of Pre-Han China (2006), ISBN 978-0-253-34025-2.

Non-English

- (French) Chavannes, Édouard, trans. (1895–1905). Les Mémoires historiques de Se-ma Ts'ien [The Historical Memoirs of Sima Qian], 6 vols.; rpt. (1967–1969) 7 vols., Paris: Adrien Maisonneuve. Left uncompleted at Chavannes' death. William Nienhauser calls it a "landmark" and "the standard by which all subsequent renditions... must be measured." [27]

- (French) Chavannes, Édouard, Maxime Kaltenmark Jacques Pimpaneau, translators. (2015) Les Mémoires historiques de Se-Ma Ts'ien [The Historical Memoirs of Sima Qian], 9 vols.; Éditions You Feng, Paris. This is the completed full translation of the Shiji

- (Russian) Vyatkin, Rudolf V., trans. (1972–1996). Istoricheskie Zapiski (Shi-czi) [Исторические записки (Ши-цзи)], 8 vols. Moscow: Nauka.

- (Mandarin) Yang, Zhongxian 杨钟贤; Hao, Zhida 郝志达, eds. (1997). Quanjiao quanzhu quanyi quanping Shiji 全校全注全译全评史记 [Shiji: Fully Collated, Annotated, Translated, and Evaluated], 6 vols. Tianjin: Tianjin guji chubanshe.

- (Japanese) Mizusawa, Toshitada 水澤利忠; Yoshida, Kenkō 吉田賢抗, trans. (1996–1998). Shiki 史記 [Shiji], 12 vols. Tokyo: Kyūko.

- (Danish) Svane, Gunnar O., trans. (2007). Historiske Optegnelser: Kapitlerne 61-130, Biografier 1-70. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- (German) Gregor Kneussel, Alexander Saechtig, trans. (2016). Aus den Aufzeichnungen des Chronisten, 3 vols. Beijing: Verlag für fremdsprachige Literatur (Foreign Languages Press); ISBN 978-7-119-09676-6.

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Nienhauser (2011), pp. 463-464.

- ↑ Hardy (1999), p. xiii.

- ↑ Hardy (1999), pp. xiii, 3.

- ↑ Durrant (1986), p. 689.

- ↑ Hulsewé (1993), pp. 405-06.

- ↑ Durrant (2001), pp. 502-03.

- 1 2 3 Knechtges (2014), p. 897.

- ↑ Kern (2010), p. 102.

- 1 2 Knechtges (2014), p. 898.

- ↑ Hulsewé (1993), p. 407.

- ↑ Hulsewé (1993), p. 409.

- ↑ Hardy, Grant (1994). "Can an Ancient Chinese Historian Contribute to Modern Western Theory? The Multiple Narratives of Ssu-Ma Ch'ien". History and Theory. 33 (1): 20–38. JSTOR 2505650.

- 1 2 Wilkinson (2012), p. 708.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Wilkinson (2012), p. 706.

- ↑ Watson (1958), pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Shiji 130: 3319, cited in Wilkinson (2012), p. 706.

- ↑ Watson (1958), pp. 95–98.

- ↑ Annals of the Five Emperors Original text: 余嘗西至空桐,北過涿鹿,東漸於海,南浮江淮矣,至長老皆各往往稱黃帝、堯、舜之處,風教固殊焉,總之不離古文者近是。

- ↑ Watson (1958), p. 183.

- ↑ Chronological table of the six kingdoms Original text: 秦既得意,燒天下詩書,諸侯史記尤甚,為其有所刺譏也。詩書所以復見者,多藏人家,而史記獨藏周室,以故滅。惜哉,惜哉!獨有秦記,又不載日月,其文略不具。

- ↑ Records of the Grand Historian, vol. Han Dynasty I, translated by Burton Watson (Columbia University, Revised Edition, 1993)

- 1 2 Watson (1958), pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph. (1954). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-521-05799-X.

- ↑ Watson (1958), p. 113.

- ↑ Watson (1958), pp. 56–67.

- ↑ Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. Brill, Leiden. pp. 8–25. ISBN 90-04-05884-2.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English p. 1282

Works cited

- Durrant, Stephen (1986). "Shih-chi 史記". In William H. Nienhauser Jr. The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature, Vol. 1. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-32983-7. OCLC 11841260.

- ——— (2001). "The Literary Features of Historical Writing". In Mair, Victor H. The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 493–510. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Hardy, Grant (1999). Worlds of Bronze and Bamboo: Sima Qian's Conquest of History. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11304-5.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1993). "Shih chi 史記". In Loewe, Michael. Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; University of California, Berkeley. pp. 405–414. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Kern, Martin (2010). "Early Chinese literature, Beginnings through Western Han". In Owen, Stephen. The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1: To 1375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–115. ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0.

- Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Shi ji 史記". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Tai-ping. Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature, A Reference Guide: Part Two. Leiden: Brill. pp. 897–904. ISBN 978-90-04-19240-9.

- Nienhauser, William (2011). "Sima Qian and the Shiji". In Feldherr, Andrew; Hardy, Grant. The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 1: Beginnings to AD 600. Oxford University Press. pp. 463–484. ISBN 0-19-103678-1.

- Watson, Burton (1958). Ssu Ma Ch'ien Grand Historian Of China. Columbia University Press.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012). Chinese History: A New Manual. Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series 84. Cambridge, MA: Harvard-Yenching Institute; Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

External links

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Full text of the Shiji (Chinese) Traditional / Simplified - Chinese Text Project

- The Original Text in its Entirety (Chinese)

- CHINAKNOWLEDGE Shiji 史記 Records of the Grand Scribe.

- Ssuma Ch'ien at Internet Sacred Text Archive. Chapters 1–3, Ssuma Ch'ien's Historical Records, translated by Herbert J. Allen:

- "Introductory Chapter" (1894), Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26 (2): 269–295. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00143916. (text)

- "The Hsia Dynasty" (1895), Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 27 (1): 93–110. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00022784. (text)

- "The Yin Dynasty" (1895), Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 27 (3): 601–615. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00145083. (text)

- Part of chapter 63 The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East, Volume XII: Medieval China, ed. Charles F. Horne, 1917, pp. 396–398.

.svg.png)