Requiem for a Dream

| Requiem for a Dream | |

|---|---|

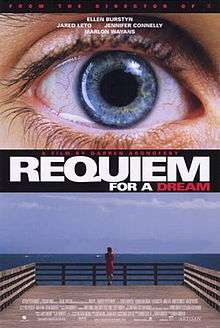

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Darren Aronofsky |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Requiem for a Dream by Hubert Selby, Jr. |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Clint Mansell |

| Cinematography | Matthew Libatique |

| Edited by | Jay Rabinowitz |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Artisan Entertainment |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 101 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4.5 million |

| Box office | $7.4 million[2] |

Requiem for a Dream is a 2000 American psychological drama film directed by Darren Aronofsky and starring Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, and Marlon Wayans. The film is based on the novel of the same name by Hubert Selby, Jr., with whom Aronofsky wrote the screenplay. Burstyn was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance. The film was screened out of competition at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival.[3]

The film depicts four different forms of drug addiction, which lead to the characters’ imprisonment in a world of delusion and reckless desperation that is subsequently overtaken by reality, thus leaving them as hollow shells of their former selves.[4][5]

Plot

During the summer in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, widow Sara Goldfarb constantly watches television, particularly infomercials hosted by Tappy Tibbons. After receiving an unexpected phone call that she has won a spot to participate on a television game show, she becomes obsessed with regaining the youthful appearance she possesses in an old photograph. To reach her goal, she goes to a doctor to discuss weight loss. The doctor gives her a prescription for weight-loss amphetamine pills throughout the day and a sedative at night. As the months go by, Sara's tolerance for the pills adjusts and as a result she is no longer able to feel the same high the pills once gave her. When her invitation does not arrive, she increases her dosage from double to triple and, as a result, begins to suffer from amphetamine psychosis.

Meanwhile, Sara's son Harry, his girlfriend Marion, and friend Tyrone are all heroin addicts, and Harry funds his habit through petty theft. Tyrone decides that to support themselves, they should enter the drug trade. With the promised money, each addict hopes to achieve their dreams. At first, the trio's drug dealing business thrives. However, Tyrone is imprisoned after fleeing the scene of a drug-gang assassination and Harry uses most of their earned money to post bail. Afterward, the three find it much more difficult to find heroin due to supply being restricted by the Florida-based wholesalers. Eventually, Tyrone hears that the wholesaler is making a shipment, but the price is doubled and the minimum amount is high. Harry suggests that Marion ask for the cash from her psychiatrist in exchange for sex, which she does grudgingly, at a cost to her relationship with Harry. Tyrone and Harry go to meet the wholesaler, but the rest of the local dealers are also there, and tensions are running high. A shot rings out and the wholesaler's bodyguards respond by firing indiscriminately into the crowd. Harry returns empty-handed to Marion, who is so desperate that she has turned the apartment upside down searching for scraps, and they have a screaming argument. He leaves, and Marion calls Tyrone for the number of a pimp who trades heroin for sex. Harry convinces Tyrone that their best option is to drive to Florida to pick up and put their drug dealing business back on track.

After a series of hallucinations, Sara flees her apartment and takes a subway to the casting agency in Manhattan to confirm when she will be on the show with Tappy Tibbons. At the agency, the staff try to reassure her while they wait for paramedics. Sara is admitted to a psychiatric ward where she is given a series of degrading treatments. When none of these work, the doctor persuades a barely lucid Sara to sign approval for electroconvulsive therapy.

On the way to Miami, they are forced to visit a hospital because of Harry’s infected left arm. The doctor notices the symptoms of drug abuse and Harry and Tyrone are arrested. Back in New York, Marion meets with the dealer who gives her drugs in exchange for sex and invites her to join a party that weekend if she wants more.

In the end, Tyrone is doing hard labor in jail, being taunted by prison guards, and unable to sleep due to drug withdrawal; Harry is transferred from prison to a hospital and his arm is amputated; Sara undergoes several rounds of electroshock therapy; and Marion returns to the dealer's apartment, where the party is a private sex show in the middle of a crowded room, in which Marion has to perform.

Sara's friends come to the hospital to see her but she doesn't react to them, and both can later be seen outside on a bench crying. Harry wakes after the amputation and weeps. Tyrone lies in his prison bed haunted by memories of his mother. Marion lies on her sofa, clutching her bag of heroin. That night, Sara has a dream in which she wins the grand prize in game show with Harry as the guest of honor.

Cast

- Ellen Burstyn as Sara Goldfarb

- Jared Leto as Harry Goldfarb

- Jennifer Connelly as Marion Silver

- Marlon Wayans as Tyrone C. Love

- Christopher McDonald as Tappy Tibbons

- Mark Margolis as Mr. Rabinowitz

- Louise Lasser as Ada

- Marcia Jean Kurtz as Rae

- Sean Gullette as Arnold, Marion's psychiatrist

- Keith David as Big Tim, Marion's pimp

- Dylan Baker as Southern Doctor

- Ajay Naidu as Mailman

- Ben Shenkman as Dr. Spencer

- Hubert Selby, Jr. as Laughing guard

- Darren Aronofsky (uncredited) as Visitor

Production

The film rights to Hubert Selby, Jr.'s book were optioned by Scott Vogel for Truth and Soul Pictures in 1997 prior to the release of Aronofsky's film π.

Themes

The majority of reviewers characterized Requiem for a Dream in the genre of "drug movies", along with films like The Basketball Diaries, Trainspotting, Spun, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.[6][7]

However, Aronofsky has said:[8]

Requiem for a Dream is not about heroin or about drugs… The Harry-Tyrone-Marion story is a very traditional heroin story. But putting it side by side with the Sara story, we suddenly say, 'Oh, my God, what is a drug?' The idea that the same inner monologue goes through a person's head when they're trying to quit drugs, as with cigarettes, as when they're trying to not eat food so they can lose 20 pounds, was really fascinating to me. I thought it was an idea that we hadn't seen on film and I wanted to bring it up on the screen.

In the book, Selby refers to the "American Dream" as amorphous and unattainable, a compilation of the various desires of the story's characters.

Style

Rapid cuts in Requiem for a Dream

One of the filmmaking techniques in Requiem for a Dream is the use of rapid cuts or a hip hop montage. Whenever the characters use street drugs, a rapid succession of images illustrates their transition from sobriety to intoxication. In this scene, Harry and Tyrone deal drugs and Marion uses cocaine while she designs clothes. The speed of the footage and the cuts alternates as the characters become intoxicated and sober. | |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

As in his previous film, π, Aronofsky uses montages of extremely short shots throughout the film (sometimes termed a hip hop montage).[6] While an average 100-minute film has 600 to 700 cuts, Requiem features more than 2,000. Split-screen is used extensively, along with extremely tight closeups.[6][9] Long tracking shots (including those shot with an apparatus strapping a camera to an actor, called the Snorricam) and time-lapse photography are also prominent stylistic devices.[10]

To portray the shift from the objective, community-based narrative to the subjective, isolated state of the characters' perspectives, Aronofsky alternates between extreme closeups and extreme distance from the action and intercuts reality with a character's fantasy.[9] Aronofsky aims to subjectivize emotion, and the effect of his stylistic choices is personalization rather than alienation.[10] The camera serves as a vehicle for exploring the characters’ states of mind, hallucinations, visual distortions, and corrupted sense of time.[5]

The film's distancing itself from empathy is structurally advanced by the use of intertitles (Summer, Fall, Winter), marking the temporal progress of addiction.[10] The average scene length shortens as the film progresses (beginning around 90 seconds to two minutes) until the movie's climactic scenes, which are cut together very rapidly (many changes per second) and are accompanied by a score which increases in intensity accordingly. After the climax, there is a short period of serenity, during which idyllic dreams of what may have been are juxtaposed with portraits of the four shattered lives.[9]

Release

Requiem for a Dream premiered at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival on May 14, 2000 and the 2000 Toronto International Film Festival on September 13 before a wide release on October 27.

Rating

In the United States, the film was originally rated NC-17 by the MPAA, but Aronofsky appealed the rating, claiming that cutting any portion of the film would dilute its message. The appeal was denied and Artisan decided to release the film unrated.[11] An R-rated version was released on video, with the sex scene edited, but the rest of the film identical to the unrated version.

In the United Kingdom, the film was given an 18 certificate by the BBFC for "drug depiction, coarse language and sex".[1] In Australia the film was rated R18+ by the ACB for "drug use and adult themes".

Critical reception

Requiem for a Dream received positive reviews from critics and has a "Certified Fresh" score of 78% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 133 reviews with an average rating of 7.4 out of 10. The critical consensus states "Though the movie may be too intense for some to stomach, the wonderful performances and the bleak imagery are hard to forget."[12] The film also has a score 68 out of 100 on Metacritic , based on 32 critics indicating "generally favorable reviews."[13] Film critic James Berardinelli considered Requiem for a Dream the second best film of the decade, behind the The Lord of the Rings film trilogy.[14] Roger Ebert gave the film 3 1/2 stars out of four, stating that "What is fascinating about Requiem for a Dream,...is how well he portrays the mental states of his addicts. When they use, a window opens briefly into a world where everything is right. Then it slides shut, and life reduces itself to a search for the money and drugs to open it again."[15] Elvis Mitchell, writing for The New York Times, gave the film a positive review, stating that "After the young director's phenomenal debut with the barely budgeted Pi, which was like watching a middleweight boxer win a fight purely on reflexes, he comes back with a picture that shows maturation."[16]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian, lauded the film. "His agonising and unflinchingly grim portrait of drug abuse, taken from a novel by Hubert Selby Jr (with whom Aronofsky co-wrote the screenplay), is a formally pleasing piece of work - if pleasing can possibly be the right word."[17] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone gave the film four out of four stars and wrote that "no one interested in the power and magic of movies should miss it."[18] Owen Gleiberman, writing for Entertainment Weekly, gave the film an "A" grade. "The movie, a full-throttle mind- bender, is hypnotically harrowing and intense, a visual and spiritual plunge into the seduction and terror of drug addiction."[19] IGN gave the film a 9.0 out of 10. "The reason it works so well as a film about addiction is that, in every frame, the film itself is addictive. It's absolutely relentless, from Aronofsky's bravura cinematic techniques (split screens, complex cross-cutting schemes, hallucinatory visuals) to Clint Mansell's driving, hypnotic score (performed by the Kronos Quartet), the movie compels you to watch it."[20]

Accolades

Ellen Burstyn was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for her role as Sara Goldfarb,[21] but lost to Julia Roberts in the title role of Erin Brockovich. She was nominated for several other awards including the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress - Motion Picture Drama and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role.[22]

In 2007, Requiem for a Dream was picked as one of the 400 nominated films for the American Film Institute list AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)[23]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack was composed by Clint Mansell with the string ensemble performed by Kronos Quartet. The string quartet arrangements were written by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang.

The soundtrack has been widely praised and has subsequently been used in various forms in trailers for other films, including The Da Vinci Code, Sunshine, Lost, The Giver, I Am Legend, Babylon A.D., and Zathura. A version of the recurring theme was re-orchestrated for the film trailer for The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.[24]

The soundtrack also confirmed its popularity with the album Requiem for a Dream: Remixed, which contains remixes of the music by Paul Oakenfold, Josh Wink, Jagz Kooner, and Delerium, among others.

References

- 1 2 "REQUIEM FOR A DREAM (18)". British Board of Film Classification. November 23, 2000. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Requiem for a Dream (2000) - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. January 1, 2002. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Requiem for a Dream". Festival-Cannes.com. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Requiem for a Dream :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- 1 2 Skorin-Kapov, Jadranka (2015) Darren Aronofsky's Films and the Fragility of Hope, p.32 Bloomsbury Academic

- 1 2 3 Booker, M. (2007). Postmodern Hollywood. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-99900-9.

- ↑ Boyd, Susan (2008). Hooked. New York: Routledge. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-415-95706-0.

- ↑ "It's a punk movie". Salon.com (October 13, 2000). Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- 1 2 3 Dancyger, Ken (2002). The Technique of Film and Video Editing. London: Focal. pp. 257–258. ISBN 0-240-80420-1.

- 1 2 3 Powell, Anna (2007). Deleuze, Altered States and Film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-7486-3282-4.

- ↑ Hernandez, Eugene; Anthony Kaufman (August 25, 2000). "MPAA Upholds NC-17 Rating for Aronofsky's "Requiem for a Dream"; Artisan Stands Behind Film and Will Release Film Unrated". indieWIRE. SnagFilms. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Requiem for a Dream Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Requiem for a Dream Reviews". Metacritic. n.d. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Top 10 Movies of the Decade". ReelViews.com. Retrieved March 1, 2011

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (November 3, 2000). "Requiem for a Dream Movie Review (2000)". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ Mitchell, Elvis (October 6, 2000). "Movie Review: Requiem for a Dream". The New York Times. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Peter (January 18, 2001). "Living in Oblivion". The Guardian. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (December 11, 2000). "Requiem for a Dream". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (October 13, 2000). "Movie Review: 'Requiem for a Dream' Review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Review of Requiem for a Dream". IGN. October 20, 2000. Retrieved December 13, 2004.

- ↑ Lyman, Rick (March 4, 2001). "OSCAR FILMS/ACTORS: An Angry Man and an Underused Woman; Ellen Burstyn Enjoys Her Second Act". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Award Nominees – 2000". The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Oscars.org. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ↑ AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) Ballot

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Answer Man". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

External links

- Requiem for a Dream at the Internet Movie Database

- Requiem for a Dream at AllMovie

- Requiem for a Dream at Box Office Mojo

- Requiem for a Dream at Rotten Tomatoes

- Requiem for a Dream at Metacritic