Crease (cricket)

In the sport of cricket, the crease is a certain area demarcated by white lines painted or chalked on the field of play, and pursuant to the rules of cricket they help determine legal play in different ways for the fielding and batting side. They define the area within which the batsmen and bowlers operate. The term crease may refer to any of the lines themselves, particularly the popping crease, or to the region that they demark. Law 9 of the Laws of Cricket governs the size and position of the crease markings, and defines the actual line as the back edge of the width of the marked line on the grass, i.e., the edge nearest to the wicket at that end.

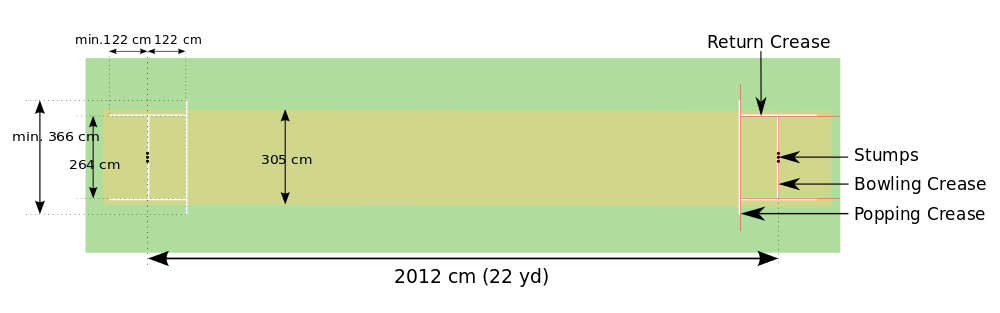

Four creases (one popping crease, one bowling crease, and two return creases) are drawn at each end of the pitch, around the two sets of stumps. The batsmen generally play in and run between the areas defined by the creases at each end of the pitch. The bowling creases lie 22 yards (66 feet or 20.12 m) away, and marks the other end of the pitch. For the fielding side, the crease defines whether there is a no ball because a fielder has encroached on the pitch or the wicket-keeper has moved in front of the wicket before they are permitted to do so. In addition, historically part of the bowler's back foot in the delivery stride was required to fall behind the bowling crease to avoid a delivery being a no ball. This rule was replaced by a requirement that part of the bowler's front foot in the delivery stride must fall behind the popping crease (see below).

History

The origin of creases is uncertain but they were certainly in use by the beginning of the 18th century when they were created by scratch marks, the popping crease being 46 inches in front of the wicket at each end of the pitch. In the course of time, the scratches became cuts which were an inch deep and an inch wide. The cut was in use until the second half of the 19th century.[1] Sometime during the early career of Alfred Shaw, he suggested that the creases should be made by lines of whitewash and this was gradually adopted through the 1870s.[2]

Popping crease

The origin of the term "popping crease" is unknown. One popping crease is drawn at each end of the pitch in front of each set of stumps. The popping crease is 4 feet (1.22 m) in front of and parallel to the bowling crease. Although it is considered to have unlimited length (in other words, runs across the entire field) the popping crease must be marked to at least 6 feet (1.83 metres) perpendicular to the pitch, on either side of the middle of the pitch.[3][4]

For the fielding side

For the fielding team the popping crease is used as one test of whether the bowler has bowled a no ball. To avoid a no ball, some part of the bowler's front foot in the delivery stride (that is, the stride when he releases the ball) must be behind the popping crease, although it does not have to be grounded. The foot may be on the line as long as some part of his/her foot is behind the line.[3][5] This has given rise to the term "the line belongs to the umpire."[6]

For the batting side

For a batsman the popping crease – which can be referred to as the batting crease in the context of batting – determines whether they have been stumped or run out. This is described in Laws 29, 38, and 39 of the laws of cricket.[4] Both involve the wicket being put down before a batsman can touch his body or bat to the ground behind the popping crease and make his ground and return safely from his run.[7] A 2010 amendment to Law 29 clarified the circumstance where the wicket is put down while a batsman has become fully airborne after having first made his ground; the batsman is regarded to not be out of his ground.[8]

- If the batsman facing the bowler (the striker) steps out of his ground to play the ball but misses and the wicket-keeper takes the ball and puts down the wicket, then the striker is out stumped.[4]

- If a fielder puts down either wicket whilst the batsmen are running between the wickets (or otherwise forward of the popping crease during the course of play), then the batsman nearest the downed wicket is out run out. There is no limit of how far a bowler may bowl behind the crease.[3]

-

The popping crease is visible here, with England's Marcus Trescothick playing a shot that has involved him moving forward over his own crease to intercept the ball. In taking a successful run, he must ground his bat behind the corresponding crease at the other end of the pitch, and his batting partner must in turn ground himself behind Trescothick's crease.[1] Should Trescothick have ventured beyond his crease in playing his shot, he risked being stumped.[2][1]

-

Jim Allenby bowling, he must ground some part of his foot behind his popping crease and within the return creases for the ball to be a legal delivery. As a member of the fielding side, he can also attempt to run out a batsman by breaking the stumps with the ball before the batsman manages to return to the popping crease.[2][1]

-

Here the batsman has played a shot and missed, with the wicketkeeper receiving the ball. The 'keeper, believing that in playing his shot the batsman has ventured beyond his popping crease, has broken the stumps with the ball in an attempt to dismiss him 'stumped'. He is appealing to the umpire to review and either accept or refuse the dismissal. It now falls to the umpire to adjudge whether the batsman had indeed ventured beyond his crease, a decision that in modern cricket is assisted by technology and replays.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Law_29_When_a_Batsman_is_Out_of_his_Groundwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Law_9_Bowling.2C_Popping_and_Return_Creaseswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Return crease

Four return creases are drawn, one on each side of each set of stumps. The return creases lie perpendicular to the popping crease and the bowling crease, 4 feet 4 inches (1.32 m) either side of and parallel to the imaginary line joining the centres of the two middle stumps. Each return crease line starts at the popping crease but the other end is considered to be unlimited in length and must be marked to a minimum of 8 feet (2.44 m) from the popping crease.[3][4]

The return creases are primarily used to determine whether the bowler has bowled a no ball. To avoid a no ball, some part of the bowler's back foot in the delivery stride must land within and not touch the return crease. This is to stop the bowler from bowling at the batsmen from an unfair angle (i.e. diagonally).[3]

Using the crease

Though the relatively small size of the crease is such that they limit the degree to which a batsman or a bowler can alter where they stand to face or deliver a ball, there is a degree of latitude afforded whereby both can move around the crease as long as they remain within the aforementioned confines. Batsmen 'use the crease' when they move toward leg or off, before or while playing a shot. Bowlers 'use the crease' by varying the position of their feet, relative to the stumps, at the moment of delivery. In so doing, they can alter the angle of delivery and the trajectory of the ball.[4]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Altham, p. 25.

- ↑ Altham, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Law 9 Bowling, Popping and Return Creases". Marylebone Cricket Club. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Law 29 When a Batsman is Out of his Ground". Marylebone Cricket Club. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "Law 24 No Ball". Marylebone Cricket Club. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "Cricket for beginners – part II". BBC News. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "Law 18 Scoring Runs". Marylebone Cricket Club. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ "MCC announce eight Law changes". 30 September 2010.

- Sources

- The Laws of Cricket at Lord's Cricket Ground

- Altham, H. S. (1962). A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914). George Allen & Unwin.

- The Laws of Cricket. Wisden. 2010.

- MCC Laws of Cricket. Marylebone Cricket Club. 1993.

- Rundell, M. and M. Atherton (2008). The Original Laws of Cricket. Bodleian Library. ISBN 1851243127.