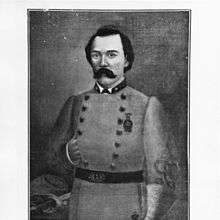

Richard W. Dowling

| Richard William "Dick" Dowling | |

|---|---|

Richard Dowling | |

| Nickname(s) | Dick |

| Born |

1837 Milltown, County Galway, Ireland |

| Died |

September 23, 1867 (aged 29–30) Houston, Texas |

| Place of burial | St Vincent's Cemetery, Navigation Blvd, Houston, Texas |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | Jefferson Davis Guards |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Richard William "Dick" Dowling (1837 – September 23, 1867) was the victorious commander at the Second Battle of Sabine Pass in the American Civil War.

Biography

Dowling was born in Knockballyvisteal, Milltown, near Tuam, County Galway, Ireland in 1837, the second of eight children, born to tenant farmer Patrick and Bridget Dowling (née Qualter). Following eviction of his family from their home in 1845, the first year of the Great Famine, nine-year-old Dowling left Ireland with his older sister Honora, bound for to New Orleans in the United States in 1846.[1]:32–49 As a teenager, young Dick Dowling displayed his entrepreneurial skills by successfully running the Continental Coffeehouse, a saloon in the fashionable French Quarter. His parents and siblings followed from Ireland in 1851, but the joy of reunion was short-lived. In 1853, a Yellow Fever outbreak in New Orleans took the lives of his parents and one of his younger brothers. With rising anti-Irish feeling growing in New Orleans, following local elections which saw a landslide victory for the 'Know Nothing' party, Dowling moved to Houston in 1857, where he leased the first of a number of saloons, a two story building centrally located on the corner of Main and Prairie Streets. He named it the Shades, from the sycamore and cottonwood trees which lined the two streets and shaded the building. Advertised as 'inferior to none in the state' he opened a billiards saloon on the first floor. Dowling was described as a likable red-headed Irishman and wore a large moustache, possibly to make him appear older than he looked, as he was called 'The Kid' by family and friends alike at this time. In 1857 he married Elizabeth Ann Odlum, daughter of Benjamin Digby Odlum, a Kildare-born Irishman, who had fought in the Texas War of Independence, being captured at the Battle of Refugio in 1836. Following Texas Independence, he was elected subsequently to the fledgling Third Congress of the Republic of Texas.

Business and Civic interests

By 1860, Dowling owned a number of saloons. His most successful was named the Bank of Bacchus,[2] located on Courthouse Square in downtown Houston. "The Bank" as it was known locally became Houston's most popular social gathering place in the 1860s and was renowned for its hospitality. Dowling's previous experience as a barkeeper in New Orleans stood him in good stead. Quickly establishing himself, Dowling courted publicity from local newspapers and also made a number of property investments. He was also involved in setting up Houston's first gaslight company, and was first to have it installed in his home and "The Bank". Dowling was a founding member of Houston's Hook and Ladder Company Number One fire department and was also involved in running the city's first streetcar company[1]:167–175

Civil War

Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Dowling had made a name for himself as an able and successful entrepreneur. Among other things, he and had been involved with a predominantly Irish militia company which served a more social than military role in Houston society. On Secession this militia company was mustered straight into the Confederate Army, with Dowling himself being elected First Lieutenant. Composed primarily of Houston Irish, many of them clients from his saloons, this unit named themselves the "Jefferson Davis Guards" in honor of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who had been in Texas as a young officer in the pre-war Union Army and was remembered for his prowess and leadership skills. The Davis Guards were initially part of a Texas State Troops/Confederate expedition sent to take over Union Army forts and arsenals along the border with Mexico; the expedition was successfully completed without a shot being fired. They participated in the Battle of Galveston on New Year's Day 1863, following which they were assigned to a newly constructed artillery post near the mouth of Sabine River called "Fort Sabine" (later named "Fort Griffin", not the same as the later Fort Griffin established west of Fort Worth).

Sabine Pass was important as a point of arrival and departure for blockade runners. With the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863, followed by the Battle of Gettysburg, it was obvious that the Civil War was now not going well for the Confederacy, an invasion of Texas appeared to be imminent. It was suspected that the Union Army would attempt an invasion of Texas via Sabine Pass, because of its value as a harbor for blockade runners and because about 18 miles northwest was Beaumont, on the railroad between Houston and the eastern part of the Confederacy.

To negotiate Sabine Pass all vessels except small boats took one of the two river channels, both of about 5 feet (1.5 meters) depth and one on each side of the Pass. These channels were separated by naturally formed "oyster-banks" known to be barely two feet (0.60 meter) under the surface. No seagoing ship could traverse the Pass without great risk of going aground, if it did not follow one of the channels. The inevitable course of any steam-powered warship—including shallow-draft gunboats then common to the U.S. Navy—would necessarily use one of the channels, both of which were within fair range of the fort's six smoothbores.

Dowling spent the summer of 1863 at the earthen fort instructing his men in gunnery. To mark the optimum distance and elevation for each of the guns, he implemented the technique of setting long slender poles (painted white, in this instance) in both channels at several places. This was an old method for guiding boats and, especially since the advent of firearms, to mark an aiming points for guns.

On September 8, 1863 a Union Navy flotilla of some 22 gunboats and transports with 5,000 men accompanied by cavalry and artillery arrived off the mouth of Sabine Pass. The plan of invasion was sound, but monumentally mismanaged. Four of the flanking gunboats were to steam up the pass at speed and draw the fire of the fort, two in each channel, a tactic which had been used successfully in subduing the defensive fortifications of Mobile and New Orleans prior to this, when gunboats disabled the forts at close range with their own guns. This time, though, Dowling's artillery drills paid off as the Confederates poured a rapid and withering fire onto the incoming gunboats, scoring several direct hits, disabling and capturing two, while the others retreated in disarray. The rest of the flotilla retreated from the mouth of the pass and returned ignominiously to New Orleans, leaving the disabled ships with no option but to surrender to Dowling. With a command of just 47 men, Lieut. Dowling had thwarted an attempted invasion of Texas, in the process capturing two gunboats, some 350 prisoners and a large quantity of supplies and munitions.[3]

The Confederate government offered its gratitude and admiration to Dowling, now promoted to Major, and his unit, as a result of their battlefield prowess[4] . In gratitude, the ladies of Houston presented the unit with specially struck medals.[5] The medals were actually Mexican eight reale coins with both faces sanded down and with new information carved into them. They were inscribed "Sabine Pass, 1864" on one side, and had a Maltese Cross with the letters D and G on the other.[6] Because of the official recognition given to the action, it is now accepted that these Davis Guard Medals are the only medals of honor issued by the Confederate government, and consequently are collector's items today.

After the war and death

After the battle of Sabine Pass Dowling was elevated to hero status in his hometown of Houston. He subsequently served as a recruiter for the Confederacy and was personally commended for his action at the battle by Jefferson Davis. After the war Dowling returned to his saloon business in Houston and quickly became one of the city's leading businessmen. Dowling's promising future was cut short by another yellow fever epidemic which devastated Houston in the late summer of 1867, and he died on September 23, 1867.

He was buried at St. Vincent's Catholic Cemetery, the oldest Catholic cemetery in Houston.[7]

Memorials and Monuments

In 1905, by public demand, the city of Houston commissioned a statue of Dick Dowling, and it stood outside City Hall until 1939 when it was moved to Sam Houston Park.[8] When the city hall was moved to a newer building in 1958 the statue was relocated to Hermann Park, near the monument to Sam Houston, where it remains today. Dowling's statue has appeared numerous times in local newspapers as his sword was repeatedly stolen by pranksters. In 1997, the Dick Dowling Society completed restoration on Dowling's statue. Annually, usually on the Saturday closest to St. Patrick's Day, the Dick Dowling Irish Heritage Society holds a commemoration ceremony at the statue. This event is regularly attended by a number of the descendants of Dick's sisters. Dick and Elizabeth had two children that survived to adulthood, Mary Anne Dowling and Felix "Richard" Sabine Dowling.[9]

In Houston, Dowling's legacy is remembered in the naming of Dowling Street, a major artery of the city's predominantly African-American Third Ward and Dowling Middle School, a middle school that serves the city's predominantly African-American and Hispanic south side. Tuam Street, another major artery named for Tuam, is also named in Dowling's honor by recognizing his place of birth in Ireland. There are similarly named streets in towns and cities across east Texas, notably Port Arthur and Beaumont, as well as memorials to Dowling and the Davis Guards, not least at Sabine Pass, where the battleground is now preserved as a state park where the battle is re-enacted every September.

In 1998, the town of Tuam, also placed a bronze memorial plaque of Dowling on its Town Hall facade bearing his image and explaining his feats.[10] This is the first known memorial to an Irish-born Confederate soldier in Ireland.

Text of plaque: "Major Richard W. (Dick) Dowling C.S.A., 1837-1867 Born Knock, Tuam; Settled Houston Texas, 1857; Outstanding business and civic leader; Joined Irish Davis Guards in American Civil War; With 47 men foiled Invasion of Texas by 5000 federal troops at Sabine Pass, 8 Sept 1863, a feat of superb gunnery; formed first oil company in Texas; Died aged 30 of yellow fever. This plaque was unveiled by Col. J.B. Collerain 31 May 1998"

Recent publications:

Collins, Timothy. 'Dick Dowling: Galway's hero of Confederate Texas', by Timothy Collins and Ann Caraway Ivins; foreword by Edward T. Cotham Jr. Kilnaboy: Old Forge Books, 2013.

Cotham, Edward T. Jr. 'Battle on the Bay: the Civil War struggle for Galveston', by Edward T. Cotham Jr. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998.

Cotham, Edward T. Jr. 'Sabine Pass: the Confederacy's Thermopylae', by Edward T. Cotham Jr. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Cotham, Edward T. Jr, ed. 'The Southern journey of a Civil War marine: the illustrated note-book of Henry O. Gusley', edited and annotated by Edward T. Cotham Jr. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006.

- Grave of Dick Dowling, St. Vincent's Cemetery

Richard Dowling Memorial Statue in Hermann Park, Houston, TX

Richard Dowling Memorial Statue in Hermann Park, Houston, TX- Richard Dowling Plaque, Tuam, Co. Galway

References

- 1 2 Dick Dowling: Galway's hero of Confederate Texas, by Timothy Collins and Ann Caraway Ivins. Old Forge Books, 2013

- ↑ map showing the location of the Bank of Bacchus

- ↑ Dallas Historical Society. "Bound For Texas: The Civil War". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Library of Congress. "Journal of the Confederate Congress --FIFTY-FOURTH DAY--TUESDAY, February 9, 1864". Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ MedalofHonor.com. "Confederate Honor Roll". Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Brian Dowling. "1st. Lt. Richard W. Dowling". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Davis, Rod. "Houston's really good idea Bus tour celebrates communities that forged a city." San Antonio Express-News. Sunday August 3, 2003. Travel 1M. Retrieved on February 11, 2012.

- ↑ Texas Escapes Online Magazine. "Dick Dowling Statue". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Bill W. Smith, Jr. "Family Trees of Bill W. Smith, Jr.". Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Sabine Pass Battleground State Historic Park, Archeological Report #8, Antiquities Permit #21 by T. Holtzapple and Wayne Roberson. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Historic Sites and Restoration Branch, Austin, Texas, Sept. 1976.

- Dick Dowling, Tuam Emigrant-Texan Hero, in pages 42–58 of Glimpses of Tuam since the Famine by Patrick Denis O'Donnell, Old Tuam Society, Tuam, 1997. ISBN 0-9530250-0-4

- The Thermopylae of Lieutenant Dick Dowling, in The Irish Sword by Patrick Denis O'Donnell, VOL.XXIII, no.91, Military History Society of Ireland, Dublin, Summer 2002 (pages 68–86)