Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant

| Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant | |

|---|---|

Seabrook Station (2009) | |

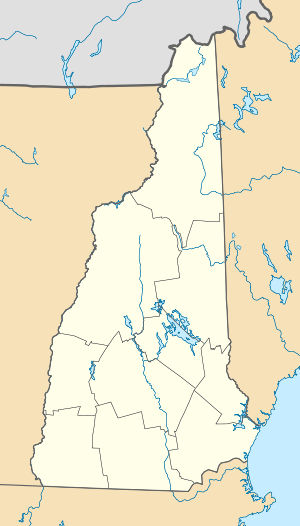

Location of the Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant in New Hampshire | |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Seabrook, New Hampshire |

| Coordinates | 42°53′56″N 70°51′03″W / 42.89889°N 70.85083°WCoordinates: 42°53′56″N 70°51′03″W / 42.89889°N 70.85083°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Commission date | March 15, 1990 |

| Owner(s) | NextEra Energy Resources |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | PWR |

| Reactor supplier | Westinghouse |

| Cooling source | North Atlantic Ocean |

| Cooling towers | no |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | 1 X 1,194 MW |

| Make and model | General Electric |

| Nameplate capacity | 1244 MW |

| Average generation | 10,763 GWh |

|

Website www.fpl.com | |

The Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, more commonly known as Seabrook Station, is a nuclear power plant located in Seabrook, New Hampshire, United States, approximately 40 miles (64 km) north of Boston and 10 miles (16 km) south of Portsmouth. Two units (reactors) were planned, but the second unit was never completed due to construction delays, cost overruns and troubles obtaining financing. The construction permit for the plant was granted in 1976, and construction on Unit 1 was completed in 1986. Full power operation of Unit 1 began in 1990. Unit 2 has been canceled and most of its major components sold to other plants. With its 1,244-megawatt electrical output, Seabrook Unit 1 is the largest individual electrical generating unit on the New England power grid. It is the second largest nuclear plant in New England after the two-unit Millstone Nuclear Power Plant in Connecticut.

History

The construction of Seabrook Station was completed ten years later than expected, with a cost approaching $7 billion. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) described its own regulatory oversight of Seabrook as "a paradigm of fragmented and uncoordinated government decision making," and "a system strangling itself and the economy in red tape."[1] The large debt involved led to the bankruptcy of Seabrook's major utility owner, Public Service Company of New Hampshire. At the time, this was the fourth largest bankruptcy in United States corporate history.[2]

The plant was originally owned by more than 10 separate utility companies serving five New England states. In 2002, most sold their shares to FPL Energy (a subsidiary of FPL Group), later known as NextEra Energy Resources. NextEra Energy now owns 88.2% of Seabrook Station. The remaining portion is owned by municipal utilities in Massachusetts.

The station is one of five nuclear generating facilities operated by FPL Group. The other four are St. Lucie Nuclear Power Plant and Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station operated by sister company Florida Power & Light (a regulated utility), and the Duane Arnold Energy Center and Point Beach Nuclear Generating Station operated by NextEra.

G4S Secure Solutions, formerly known as the Wackenhut Corporation, provides plant security to three of the four sites. Seabrook, St. Lucie, and Turkey Point experienced security related problems between 2004 and 2006. At Seabrook, US congressmen and the NRC investigated reports that a newly installed security fence had not worked properly since its installation six months earlier, in addition to reports of overworked security officers.[3][4][5][6][7]

Public opposition

In the eight years before construction started at Seabrook, residents had opposed the plant before regulatory agencies and in a town meeting vote. Spurred on by the failure of these methods, and the success of a large anti-nuclear site occupation in Whyl, Germany, local people formed the Clamshell Alliance.[8]

On August 1, 1976, 600 protestors rallied at the Seabrook Station construction site. In May 1977, more than 2,000 protestors, including 1,400 members of the Clamshell Alliance, occupied the site. Of the protestors, 1,414 were arrested and held for two weeks after they refused bail.[8][9]

Another vocal opponent of the plant was then Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, who blocked the opening for several years due to environmental issues as well as concern about emergency evacuation plans. The NRC had stipulated that workable evacuation plans needed to be in place for all towns within a 10-mile (16 km) radius of the plant. Four Massachusetts towns were within the ten-mile radius, and thus Governor Dukakis' approval of evacuation plans was required.[2]

A lawsuit complaining that the NPP would cause thermal pollution was launched by anti-nuclear opposition. This was rejected without merit, but it delayed construction by 7.5 months.[10] These protests and lawsuits are the reason the plant cost double initial estimates.[10]

Relicensing

In 2010, the plant applied to have its operating license extended from 2030 to 2050.[11] In September 2012, Massachusetts Reps. Edward Markey and John F. Tierney filed HR 6554, titled the "Nuclear Reactor Safety First Act".[12] The bill would prevent nuclear plants from receiving 20-year license extensions from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission if they apply more than 10 years before their current 40-year licenses expire. The legislation was specifically aimed at Seabrook Station, which is currently experiencing aging-related problems 22 years into its operating license. The representatives have asserted that granting the plant a license extension covering operation from 2030 to 2050 based on inspections done in 2012 is illogical. They believe that inspection dates more than 10 years before the expiration of the current license are too far from the dates of validity for the extension and therefore may miss additional age-related problems that may occur in the future.

As of February 2012, there are safety concerns about concrete degradation at the plant. Concrete surrounding an electric control tunnel at the nuclear plant has lost almost 22 percent of its strength and is showing signs of an alkali–silica reaction (ASR) because of more than a decade of ground-water infiltration, according to an NRC inspection report released in May 2011. A growing chorus of local politicians is "urging the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to halt the relicensing process for Seabrook Station until a long-term solution is implemented."[13]

Second reactor

A second reactor was proposed in 1972 and canceled in 1988.[14] It was 22% complete.

During the 2008 presidential election, Republican nominee John McCain mentioned the possibility of building the once-planned second reactor at Seabrook. The idea drew cautious support from some officials, but would be difficult due to financial and regulatory reasons.[15]

Technical details

- Generation: 1,296 MWe at full power (since uprate)

- One Westinghouse pressurized water reactor

- Cooled by water from the Gulf of Maine

Surrounding population

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission defines two emergency planning zones around nuclear power plants: a plume exposure pathway zone with a radius of 10 miles (16 km), concerned primarily with exposure to, and inhalation of, airborne radioactive contamination, and an ingestion pathway zone of about 50 miles (80 km), concerned primarily with ingestion of food and liquid contaminated by radioactivity.[16]

The 2010 U.S. population within 10 miles (16 km) of Seabrook was 118,747, an increase of 10.1 percent in a decade, according to an analysis of U.S. Census data for msnbc.com. The 2010 U.S. population within 50 miles (80 km) was 4,315,571, an increase of 8.7 percent since 2000. Cities within 50 miles include Boston (40 miles to city center).[17]

Seismic risk

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission's estimate of the risk each year of an earthquake intense enough to cause core damage to the reactor at Seabrook was 1 in 45,455, according to an NRC study published in August 2010.[18][19]

Notes

- ↑ quoted by US EPA Commissioner Kennedy, in [Decisions of the United States Environmental Protection Agency], v.1 p.490.

- 1 2 Clamshell Alliance: Thirteen Years of Anti-Nuclear Activism at Seabrook, New Hampshire, U.S.A.

- ↑ Portsmouth Herald Local News: Nuke plant fence was 'inoperable'

- ↑ Hampton Union Local News: Congressmen question NRC

- ↑ Portsmouth Herald Editorial: Public has right to know about failed Seabrook Station fence

- ↑ Fosters.com - Dover NH, Rochester NH, Portsmouth NH, Laconia NH, Sanford ME

- ↑ Fosters.com - Dover NH, Rochester NH, Portsmouth NH, Laconia NH, Sanford ME

- 1 2 Steve E. Barkan. Strategic, Tactical and Organizational Dilemmas of the protest Movement Against Nuclear Power Social Problems, Vol. 27, No. 1, October 1979, p. 24.

- ↑ "The Siege of Seabrook - TIME". Time. May 16, 1977.

- 1 2 Morris, Robert C. (2000). The environmental case for nuclear power : economic, medical, and political considerations. St. Paul, Minn.: Paragon House. pp. 171–2. ISBN 1-557-78780-8.

- ↑ GraniteGeek:Seabrook nuke plant seeks another 20 years of life

- ↑ Edward Markey (September 26, 2012). "Reps. Tierney, Markey Introduce Legislation to Ensure Safety of Nuclear Plants for Local Families".

- ↑ Brenda J. (February 9, 2012). "Local leaders question safety of Seabrook power plant". Boston Globe.

- ↑ Nuclear Power Generation and Fuel Cycle Report 1997 p. 67.

- ↑

- ↑ "Backgrounder on Emergency Preparedness at Nuclear Power Plants". U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ↑ Bill Dedman, Nuclear neighbors: Population rises near US reactors, msnbc.com, April 14, 2011 http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/42555888/ns/us_news-life/ Accessed May 1, 2011.

- ↑ Bill Dedman, "What are the odds? US nuke plants ranked by quake risk," msnbc.com, March 17, 2011 http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/42103936/ Accessed April 19, 2011.

- ↑ Patrick Hiland (September 10, 2010). "Memo: Safety/Risk Assessment Results for Generic Issue 199, "Implications of Updated Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Estimates in Central and Eastern United States on Existing Plants"" (PDF). MSNBC. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant. |

- Information on Seabrook Station, at NextEra Energy site

- Department of Energy Seabrook Page

- Photo essay on the mass arrests at the Seabrook anti-nuclear rally in 1977 at motherjones.com

- Seabrook, NH Nuclear Plant Occupation Page with timeline, scanned articles 1977-2007, images and links