Second East Turkestan Republic

| East Turkestan Republic | ||||||||||

| شەرقىي تۈركىستان جۇمھۇرىيىتى 東突厥斯坦共和國 | ||||||||||

| Satellite state of the Soviet Union[1][2][3][4] | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

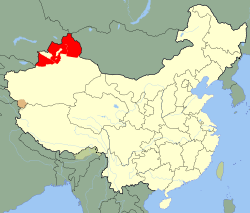

The Ili, Tarbagatay, and Altay districts (red) in which the East Turkestan Republic orgiinated before expanding to all of "Xinjiang". | ||||||||||

| Capital | Ghulja[5] | |||||||||

| Languages | Uyghur Kazakh Russian | |||||||||

| Government | Single-party socialist republic[2][6] | |||||||||

| President | Ali Khan Türe (1944–1946) | |||||||||

| Ehmetjan Qasimi (1946–1949) | ||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Established | November 12, 1944 | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | December 20, 1949 | ||||||||

| Currency | Som | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

The Second East Turkestan Republic, commonly referred to simply as the East Turkestan Republic (ETR), was a short-lived Soviet-backed Turkic socialist people's republic. The ETR existed in the 1940s (November 12, 1944 – December 20, 1949) in Xinjiang. It began as a revolution in three northern districts (Ili, Tarbaghatai, Altai) of Xinjiang Province of the Republic of China, resulting in the Ili Rebellion. The rest of Xinjiang was under Kuomintang control. This region is now the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). ETR was the first phase of the Three Districts Revolution (1944-1949).

Background

From 1934 to 1941 Xinjiang was under the influence of the Soviet Union. The local warlord Sheng Shicai was dependent on the Soviet Union for military support and trade. Soviet troops entered Xinjiang twice, in 1934 and 1937, for a limited periods of time to give direct military support to Sheng Shicai's regime. After suppressing the 36th Division General Ma Chung-yin in 1934 and the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1935, the USSR sent a commission to Xinjiang to draw up a plan for reconstruction of the province, led by Stalin's brother-in-law, Deputy Chief of Soviet State Bank, Alexander Svanidze, which resulted in a Soviet five-year loan of five million gold rubles to Sheng Shicai's regime. The draft was signed by Sheng Shicai on May 16, 1935, without consultation or approval by the Central Government of China. After Soviet intervention in 1937 and quelling of both Tungan and Uyghur rebels on the South of Xinjiang with liquidation of the 36th Tungan Division and 6th Uyghur Division, the Soviet Government did not withdraw all Soviet troops. A regiment of soldiers from the Ministry of Internal Affairs remained in Kumul beginning in October 1937, in order to prevent a possible offensive from the Imperial Japanese Army into Xinjiang through Inner Mongolia. In exchange, concessions were granted for oil wells, tin and tungsten mines, and trade terms highly favorable to the USSR.

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 20,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslim Kazakhs, until only 135 remained.[7][8]

On November 26, 1940, Sheng Shicai concluded an Agreement granting the USSR additional concessions in the province of Xinjiang for fifty years, including areas bordering India and Tibet. This placed Xinjiang under virtually full political and economic control of the USSR, making it part of China in name only. Sheng Shicai recalled in his memoir, "Red failure in Sinkiang," published by the University of Michigan in 1958, that Joseph Stalin pressured him to sign the secret Agreement of Concessions in 1940. The Agreement of Concessions, prepared by Stalin and seventeen articles long, would have resulted in Xinjiang sharing the same fate as Poland. Sheng Shicai was informed of this intended result by Soviet representatives in Urumchi Bakulin and Karpov.

The first article of Agreement stated that "The Government of Sinkiang agrees to extend to the Government of the USSR within the territory of Sinkiang exclusive rights to prospect for, investigate and exploit tin mines and its ancillary minerals." The USSR established a trust known as Sin-Tin as an independent juridical person subject only to legislative procedures of the USSR for implementation of the provisions of Agreement in accordance with Article 4 with right "to establish without hindrance branch offices, sub-branch offices and agencies within the whole territory of Sinkiang" with all supplies of needs of concessions, deliveries of equipment and materials and other imports from USSR and exports of minerals from Sinkiang free of custom duties and other imposts and taxes and payment of fixed price of five percent of the cost of mined minerals to the Xinjiang Government.[9]

Following this agreement, large-scale geological exploration expeditions were sent by the Soviets to Xinjiang in 1940 to 1941, and large deposits of diverse mineral resources, including uranium and beryllium, were found in the mountains near Kashgar and in the Altai region. Ores of both minerals continued to be delivered from Xinjiang Altai mines to the USSR until the end of 1949. Soviet geologists continued to work in Xinjiang until 1955, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev refused Mao Zedong's demand to hand over the technology to produce PRC nuclear weapons. A Chinese atomic project was initiated using facilities built by the Soviet Union in Chuguchak and Altai in Northern Xinjiang. These facilities were used by the Soviet Union for nuclear weapon design and the creation of the first Soviet atomic bomb, successfully tested in USSR on August 29, 1949. Thousands of Japanese POWs disappeared without traces during forcible participating in this project.

Following Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and the entry of the United States into World War II in December 1941, the Soviet Union became a far less attractive patron for Sheng than the Kuomintang. By 1943 Sheng Shicai switched his allegiance to the Kuomintang after major Soviet defeats at the hands of the Germans in World War II, all Soviet Red Army military forces and technicians residing in the province were expelled,[10] and the Republic of China National Revolutionary Army units and soldiers belonging to Ma Bufang moved into Xinjiang to take control of the province. Ma Bufang helped the Kuomintang build motor roadways linking Qinghai and Xinjiang, which helped both of them bring Xinjiang under their influence.[11] At August 1942 Sheng met Dekanozov, former Soviet Ambassador to Nazi Germany and Vice Commissar of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of USSR, in Urumchi and demanded that the Soviet Union withdrew all military forces and political officers from Xinjiang in 3 months and removed all Soviet equipment from the territory of Soviet Concessions, including closing of Soviet oil fields in Tushangze (Jungaria) and Soviet Aircraft Manufacturing Plant in Urumchi. On August 29, 1942, next day after Dekanozov left Urumchi, Sheng met Madame Chiang Kai-shek, wife of Chinese Generalissimo, who flew to Urumchi with letter from Chiang Kai-shek who promised his forgiveness to Sheng for all his previous deals. Sheng was appointed the head of the Kuomintang branch in Xinjiang in 1943 and allowed Kuomintang cadres into the province. To forge his ties with Kuomintang, Sheng arrested on September 17, 1942 a number of Chinese communists sent to Xinjiang by Central Committee of Communist Party of China in 1938 and executed them in 1943. Among executed was Mao Zemin, brother of Mao Zedong. In the summer of 1944, following the German defeat on the Eastern Front, Sheng attempted to reassert control over Xinjiang and turned to the Soviet Union for support again. He arrested a number of Kuomintang cadres in Urumchi and sent a letter to Stalin with offer to "incorporate Xinjiang into USSR as its 18th Soviet Socialistic Republic."[lower-alpha 1] Sheng Shicai asked Stalin for the post of a Ruler of the new Soviet Republic. Stalin refused to deal with Sheng and forwarded this confidential letter to Chiang Kai-shek. As a result, the Kuomintang removed him from the province in August 1944 and appointed him to a low-level post in the Ministry of Forestry in Chongqing.

In 1944, the Soviets took advantage of discontent among the Turkic peoples of the Ili region in northern Xinjiang to support a rebellion against Kuomintang rule in the province in order to reassert Soviet influence in the region.

Rebellion

Many of the Turkic peoples of the Ili region of Xinjiang had close cultural, political, and economic ties with Russia and then the Soviet Union. Many of them were educated in the Soviet Union and a community of Russian settlers lived in the region. As a result, many of the Turkic rebels fled to the Soviet Union and obtained Soviet assistance in creating the Sinkiang Turkic People's Liberation Committee (STPNLC) in 1943 to revolt against Kuomintang rule during the Ili Rebellion.[12] The pro-Soviet Uyghur who later became leader of the revolt and the Second East Turkestan Republic, Ehmetjan Qasim, was Soviet educated and described as "Stalin's man" and as a "communist-minded progressive".[13] Qasim Russified his surname to "Kasimov" and became a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Liu Bin-Di was a Hui Muslim Kuomintang (KMT) officer and was sent by officials in Urumqi to subdue the Hi area and crush the Turkic Muslims, who were prepared to overthrow Chinese rule. His mission failed because his troops arrived too late.[14] Several Turkic cavalry units armed by the Soviets crossed into China in the direction of Kuldja. In November 1944 Liu was killed by Turkic Uyghur and Kazakh rebels backed by the Soviet Union. This started the Ili Rebellion, with the Uyghur Ili rebel army fighting against Republic of China forces.

Following Sheng Shicai's departure from Xinjiang, the new Kuomintang administration had increasing trouble maintaining law and order. On September 16, 1944, troops that had been sent to Gongha county, a majority Kazak region, were unable to contain a group of rioters. By October 8, the rioters had captured Nilka, the county seat. During October, the Three Districts Rebellion broke out south of Ghulja in the Ili, Altay and Tarbagatay districts of northern Xinjiang. Aided by the Soviet Union, and supported by several Xinjiang exiles trained in the Soviet Union, the rebels quickly established control over the three districts, capturing Ghulja in November. The ethnic Chinese population of the region was reduced by massacre and expulsion. According to United States consular officials, the Islamic scholar Elihan Töre declared a "Turkistan Islam Government":

"The Turkestan Islam Government is organized: praise be to Allah for his manifold blessings! Allah be praised! The aid of Allah has given us the heroism to overthrow the government of the oppressor Chinese. But even if we have set ourselves free, can it be pleasing in the sight of our God if we only stand and watch while you, our brethren in religion ... still bear the bloody grievance of subjection to the black politics of the oppressor Government of the savage Chinese? Certainly our God would not be satisfied. We will not throw down our arms until we have made you free from the five bloody fingers of the Chinese oppressors' power, nor until the very roots of the Chinese oppressors' government have dried and died away from the face of the earth of East Turkestan, which we have inherited as our native land from our fathers and our grandfathers."

The rebels assaulted Kulja on 7 November 1944 and rapidly took over parts of the city, massacring KMT troops, however, the rebels encountered fierce resistance from KMT forces holed up in the power and central police stations and did not take them until the 13th. The creation of the "East Turkestan Republic" (ETR) was declared on the 15th[15] The Soviet Army assisted the Ili Uyghur army in capturing several towns and airbases. Non-communists Russians like White Russians and Russian settlers who had lived in Xinjiang since the 19th century also helped the Soviet Red Army and the Ili Army rebels. They suffered heavy losses.[16] Many leaders of the East Turkestan Republic were Soviet agents or affiliated with the Soviet Union, like Abdulkerim Abbas, Ishaq Beg, Saifuddin Azizi and the White Russians F. Leskin, A. Polinov., and Glimkin.[17] When the rebels ran into trouble taking the vital Airambek airfield from the Chinese, Soviet military forces directly intervened to help mortar the Airambek and reduce the Chinese stronghold.[18]

The rebels engaged in massacres of Han Chinese civilians, especially targeting people affiliated with the KMT and Sheng Shicai.[19] In the "Kulja Declaration" issued on 5 January 1945, the East Turkestan Republic proclaimed that it would "sweep away the Han Chinese", threatening to extract a "blood debt" from the Han. The Declaration also declared that the Republic would seek to especially establish cordial ties with the Soviets.[20] The ETR later deemphasized the anti-Han tone in their official proclamations after they were done massacring most of the Han civilians in their area.[21] The massacres against the Han occurred mostly during 1944-45, with the KMT responding in kind by torturing, killing, and mutilating ETR prisoners.[18] In territory controlled by the ETR like Kulja, various repressive measures were carried out, like barring Han from owning weapons, operating a Soviet style secret police, and only making Russian and Turkic languages official and not Chinese.[22] While the non-Muslim Tungusic peoples like the Xibe played a large role in helping the rebels by supplying them with crops, the local Muslim Tungan (Hui) in Ili gave either an insignificant and negligible contribution to the rebels or did not assist them at all.[21]

The demands of the rebels included termination of Chinese rule, equality for all nationalities, recognised use of native languages, friendly relations with the Soviet Union, and opposition to Chinese immigration into Xinjiang. The military forces available to the rebellion were the newly formed Ili National Army (INA) and later renamed the East Turkestan National Army, which included mostly Uighur, Kazakh and White Russian soldiers (around 60,000 troops, armed and trained by the Soviet Union, strengthened with regular Red Army units, that included up to 500 officers and 2,000 soldiers), and a group of Kazak Karai tribesmen under the command of Osman Batur (around 20,000 horsemen). The Kazaks expanded to the north, while the INA expanded to the south. By September 1945, the Kuomintang Army and the INA occupied positions on either side of the Manasi River near Ürümqi. By this time the ETR held Zungaria and Kashgaria, while the Kuomintang held the Ürümqi (Tihuwa) area.

The "Ili National Army" (INA) which was established on 8 April 1945 as the military arm of the ETR, was led by the Kirghiz Ishaq Beg and the White Russians Polinov and Leskin, and all three were pro Soviet and had a history of military service with Soviet associated forces.[23] The Soviets supplied the INA with ammunition and Russian style uniforms, and Soviet troops directly helped the INA troops fight against the Chinese forces.[24] The INA uniforms and flags all had insignia with the Russian acronym for "East Turkestan Republic", VTR in Cyrillic (Vostochnaya Turkestanskaya Respublika). The Soviets admitted their support of the rebels decades later when they transmitted a radio broadcast in Uyghur from Radio Tashkent into Xinjiang on 14 May 1967, boasting of the fact that the Soviets had trained and armed the East Turkestan Republic forces against China.[25] Thousands of Soviet troops assisted Turkic rebels in fighting the Chinese army.[26] In October 1945 suspected Soviet planes attacked Chinese positions.[27]

As the Soviet Red Army and Turkic Uyghur Ili Army advanced with Soviet air support against poorly prepared Chinese forces, they almost succeeded in reaching Ürümqi; however, the Chinese military threw up rings of defences around the area, sending Chinese Muslim cavalry to halt the advance of the Turkic Muslim rebels. Thousands of Chinese Muslim troops under General Ma Bufang and his nephew General Ma Chengxiang poured into Xinjiang from Qinghai to combat the Soviet and Turkic Uyghur forces.

Much of the Ili army and equipment originated from the Soviet Union. The Ili rebel army pushed the Chinese forces across the plains and reached Kashgar, Kaghlik and Yarkand. However, the Uyghurs in the oases gave no support to the Soviet-backed rebels and, as a result, the Chinese army was able to expel them. The Ili rebels then butchered livestock belonging to Kirghiz and Tajiks of Xinjiang.[28] The Soviet-backed insurgents destroyed Tajik and Kirghiz crops and moved aggressively against the Tajiks and Kirghiz of China.[29] The Chinese beat back the Soviet supported rebellion in Sarikol from August 1945 – 1946, defeating the siege of the "tribesman" around Yarkand when they had rose up in rebellion in Nanchiang around Sarikol, and killing Red Army officers.[30]

The Chinese Muslim Ma Clique warlord of Qinghai, Ma Bufang was sent with his Muslim Cavalry to Urumqi by the Kuomintang in 1945 to protect it from the Uyghur rebels from Ili.[27][31][32][33][34] In 1945, the Tungan (Hui) 5th and 42nd Cavalry were sent from Qinghai to Xinjiang where they reinforced the KMT 2nd Army, made out of 4 divisions. Their combined forces made for 100,000 Hui and Han troops serving under KMT command in 1945.[35] It was reported the Soviets were eager to "liquidate" Ma Bufang.[36] General Ma Chengxiang, another Hui Ma Clique officer and nephew of Ma Bufang, commanded the First Cavalry Division in Xinjiang under the KMT, which was formerly the Gansu Fifth Cavalry Army.[37][38][39]

A cease-fire was declared in 1946, with the Second East Turkestan Republic in control of Ili and the Chinese in control of the rest of Xinjiang, including Ürümqi.

Negotiations and Coalition Government in Ürümchi, and the end of ETR

In August 1945, China signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance granting the Soviet Union a range of concessions that the United States promised at the Yalta conference. This ended overt Soviet support for the East Turkestan Republic. The Kuomintang's central government of China reached a negotiated settlement with the leaders of the ETR in June 1946. According to the negotiated settlement, on June 27, 1946, the Committee of the Government of ETR laid down Resolution 324, to transform the Committee of the Government of ETR into the council of the Ili Prefecture of Xinjiang Province (the resolution use 'East Turkestan' to denote Xinjiang Province), and end the ETR. The new council was not a government, and the Three Districts were respectively and directly led by the newly founded Xinjiang Provincial Coalition Government as other seven districts in Xinjiang.[40]

On July 1, 1946, the Xinjiang Provincial Coalition Government was established in Ürümchi. This government was constituted by three sides: the central government of China, the Three Districts, and the Seven Districts (during that time Xinjiang Province had ten districts in total, and the anti-revolutionary Seven Districts, also the main inhabited areas of Urghur, was treated as a united side to join the Coalition Government). In the 25 members of the Committee of the Coalition Government, there were seven from the central government, eight from the Three Districts, and ten from the Seven Districts. The communist Ehmetjan Qasim, the leader of the Three Districts, became the Provincial Vice Chairman.[40][41]

After the Collapse of the Coalition Government

As the establishment of the Coalition Government, the unpopular governor Wu Zhongxin (chairman of the Government of Xinjiang Province) was replaced by Zhang Zhizhong (chairman of the Xinjiang Provincial Coalition Government), who implemented pro-minority policies to placate the minorities population in the Three Districts.

After the establishment of the Coalition Government, in effect, little changed in the Three Districts. The Three Districts remained a de facto separate pro-Soviet area with its own currency and military forces. At the beginning, all the three sides of the Coalition Government placed their hopes in it. The Three Districts side discussed with the Coalition Government and the Seven Districts to unite the economy, finance, transport, postal service systems of the ten districts in Xinjiang together again. They discussed the army reorganization of the Three Districts too. The Three Districts had retreated their army from the Seven Districts.[40]

However, as the domestic and international situation changed, and the contradiction in the Coalition Government deepened, the Coalition Government was on the verge of collapse in 1947. During 1946 and 1947, Kuomintang actively supported some politicians opposing the Three Districts. By this time, these opposition politicians included Kazak leader Osman Batur, who broke with the other rebels when their pro-Soviet orientation became clear. In the Coalition Government, there were several important Uyghurs appointed by Kuomintang, who were anti-revolution, such as Muhammad Amin Bughra, Isa Yusuf Alptekin and Masud Sabri. These three Urghur people came back to Xinjiang with Zhang Zhizhong in 1945, when the negotiations started.[42]

As there were too many difficulties, Zhang Zhizhong, the chairman of the Coalition Government, decided to escape from Xinjiang.[42] Bai Chongxi, the Defense Minister of China and a Hui Muslim, was considered for appointment in 1947 as Governor of Xinjiang.[43] But finally, according to Zhang Zhizhong's recommendation, the position was given instead to Masud Sabri, a pro-Kuomintang Uyghur who was anti-Soviet.[42][44]

On May 21, 1947, the central government appointed Masud Sabri to be the new chairman, and Isa Yusuf Alptekin to be the secretary-general of the Coalition Government. This was fiercely opposed by the Three Districts side, but supported by the Seven Districts side. Masud Sabri was close to conservatives in the CC Clique of the Kuomintang and undid all of Zhang Zhizhong's pro-minority reforms, which set off revolts and riots among the Uyghurs in the oases like Turfan (A district of the Sevent Districts. Riots in Turfan started from July 1947). On August 12, 1947, Ehmetjan Qasim (the vice-chairman of the Coalition Government and the leader of the Three Districts) left Ürümchi and went back to Ili. Soon later, all other people in the Coalition Government from the Three Districts side went back to Ili too. So the Coalition Government collapsed.[42][44]

After the collapse, the Three Districts went back to a de facto separate pro-Soviet area. However, this time the Three Districts never rebuilt the old ETR, but kept in Xinjiang Province. The leadership was firmly in the hand of communists. On February 3, 1947, the People's Revolutionary Party (in the Three Districts) and the Xinjiang Communist Union (in Ürümchi) incorporated into the Democratic Revolutionary Party (chairman was Abdulkerim Abbas), and the party constitution clearly stipulated that one of the party's goal was to oppose the 'Pan-Turkism' and 'Pan-Islam'. Ehmetjan Qasim, Abdulkerim Abbas and other leaders of the Three Districts publicly declared that the Three Districts would not be the ETR again, but must keep in Xinjiang and China. In order to establish a new organization to govern the Three Districts (from the beginning of the Coalition Government, as the Government of ETR dissolved, the Three Districts lost a united government), in August 1948, the Xinjiang Democratic League of Peace Safeguarding was organized. It was both a political party and a leader organization of the Three Districts. To be noticeable, the party used "Xinjiang" in its name, but did not use "East Turkestan". This is a milestone for the Three Districts side.[45]

At the end of Chinese Civil War, in September 1949, when Kuomintang army and provincial government of Xinjiang crossed over to the Communist Party of China (CPC) side, the Three Districts joined the CPC side, and accepted the leadership of CPC. Their revolution ended. The leaders of the Three Districts joined CPC (such as Saifuddin Azizi), and the army was reformed into the Fifth Army of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, then in 1950s transformed into a part of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.

Anti ETR Uyghurs

The KMT CC Clique employed countermeasures in Xinjiang to prevent the conservative, traditionalist religious Uyghurs in the oases in Southern Xinjiang from defecting to the pro-Soviet, pro-Russian ETR Uyghurs in Ili in Northern Xinjiang. The KMT allowed three anti-Soviet, Pan-Turkic nationalist Uyghurs, Masud Sabri, Muhammad Amin Bughra and Isa Yusuf Alptekin to write and publish pan-Turkic nationalist propaganda in order to incite the Turkic peoples against the Soviets, and the Soviets were severely angered by this.[46][47] Anti Soviet sentiment was espoused by Isa while Pro Soviet sentiment was espoused by Burhan. The Soviets were angered by Isa. Violence broke out between supporters of the Soviets and supporters of Turkey because of a film on the Russo Turkish wars in 1949 at Xinjiang College according to Abdurahim Amin in Dihua (Urumqi).[48]

The unpopular governor Wu Zhongxin was replaced after the cease-fire with Zhang Zhizhong, who implemented pro-minority policies to placate the Uyghur population. Bai Chongxi, the Defense Minister of China and a Muslim, was considered for appointment in 1947 as Governor of Xinjiang,[43] but the position was given instead to Masud Sabri, a pro-Kuomintang Uyghur who was anti-Soviet.[44] Masud Sabri was close to conservatives in the CC Clique of the Kuomintang and undid all of Zhang Zhizhong's pro-minority reforms, which set off revolts and riots among the Uyghurs in the oases like Turfan.

American telegrams reported that the Soviet secret police threatened to assassinate Muslim leaders from Ining and put pressure on them to flee to "inner China" via Tihwa (Urumqi), White Russians grew fearful of Muslim mobs as they chanted, "We freed ourselves from the yellow men, now we must destroy the white."[49]

Pan-Turkist 3 Effendis, (Üch Äpändi) Aisa Alptekin, Memtimin Bughra, and Masud Sabri were Anti-Soviet Uyghur leaders.[50] The Second East Turkestan Republic attacked them as Kuomintang "puppets".[51]

Achmad (Ehmetjan Qasim) was strongly against Masud Sabri becoming Governor.[52]

Ehmetjan Qasim (Achmad-Jan), the Uyghur Ili leader, demanded that Masud Sabri be sacked as governor and prisoners released from Kuomintang jails as some of his demands to agreeing to go to visit Nanjing.[53]

Uyghur linguist Ibrahim Muti'i opposed the Second East Turkestan Republic and was against the Ili Rebellion because it was backed by the Soviets and Stalin. The former ETR leader Saifuddin Azizi later apologized to Ibrahim and admitted that his opposition to the East Turkestan Republic was the correct thing to do.[54]

Over 60,000 soldiers were in the Ili army according to General Sung.[55]

Kazakh Defection

Osman Batur, the Kazakh leader, defected to the Kuomintang, and started fighting against the Soviet Union and the Mongolian army during the Pei-ta-shan Incident. The Tungan (Chinese Muslim or Hui) 14th Cavalry Regiment, which worked for the Kuomintang, was sent by the Chinese government to attack Soviet and Mongol Army at Peitashan on the Xinjiang-Mongolia border.

The Salar Muslim Gen. Han Youwen, who served under Ma Bufang, commanded the Pau-an-dui (pacification soldiers), composed of three 340-man battalions. They were composed of men of many groups, including Kazakhs, Mongols and White Russians serving the Chinese regime. He served with Osman Batur and his Kazakh forces in battling the Three Districts Ili Uyghur and Soviet forces.[56] The Three Districts forces in the Ashan zone were attacked, defeated, and killed by Osman's Kazakh forces during an offensive in September 1947, supported by the Chinese.[57] Osman's Kazakhs seized most of the towns in the Ashan zone from the Three Districts.[58] The acting Soviet consul at Chenghua, Dipshatoff, directed the Red Army in aiding Three Districts Ili forces against Osman's Kazakhs.[59]

Pei-ta-shan Incident

The Pei-ta-shan Incident was a border conflict between the Republic of China and the Mongolian People's Republic. The Chinese Muslim Hui cavalry regiment was sent by the Chinese government to attack Mongol and Soviet positions, resulting in the conflict.[60]

A Xinjiang police station manned by a Chinese police force with Chinese sentry posts existed in Xinjiang both before and after 1945.[61]

Chinese Muslim and Turkic Kazakh forces working for the Chinese Kuomintang, battled Soviet Russian and Mongol troops. In June 1947, the Mongols and the Soviets launched an attack against the Kazakhs, driving them back to the Chinese side of the border. Fighting continued for another year, with thirteen clashes taking place between June 5, 1947, and July 1948.[62]

Mongolia invaded Xinjiang to assist Li Rihan, the pro-Russian Special Commissioner, gain control of Xinjiang from Special Commissioner Us Man (Osman), who supported the Republic of China. The Chinese defence ministry spokesman announced that Outer Mongolian soldiers were captured at Peitashan, and stated that troops were resisting near Peitashan.[63]

Elite Qinghai Hui cavalry were sent by the Chinese Kuomintang to destroy the Mongols and the Russians in 1947.[64][65]

The Chinese troops recaptured Peitashan and continued to fight against Soviet and Mongolian bomber planes. China's Legislative Yuan demanded a firmer policy against Russia.[66]

The Chinese General Ma Xizhen and the Kazakh Osman Batur fought against the Mongol troops and airplanes throughout June, 1947.[67] The MPR used a battalion size force and had Soviet air support on June 1947.[68] The Mongolians repeatedly probed the Chinese lines.[69][70]

Osman continued to fight against the Uyghur forces of the Yili regime in north Ashan after being defeated by Soviet forces.[71]

Absorption by the People's Republic of China

In August 1949, the People's Liberation Army captured Lanzhou, the capital of the Gansu Province. Kuomintang administration in Xinjiang was threatened. The Kuomintang Xinjiang provincial leaders Tao Zhiyue and Burhan Shahidi led the government and army crossed over to the Communist Party of China (CPC) side in September 1949. By the end of 1949, some Kuomintang officials fled to Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan, but most crossed over or surrendered to the CPC. On August 17, 1949, the Communist Party of China sent Deng Liqun to negotiate with the Three Districts leadership in Ghulja (Yining in Chinese). Mao Zedong invited the leaders of the Three Districts to take part in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference later that year. The leaders of the Three Districts traveled to the Soviet Union on August 22 by automobiles through Horgos, accompanied by Soviet vice-consul in Ghulja Vasiliy Borisov, where they were told to cooperate with the Communist Party of China. Negotiations between Three Districts and Soviet representatives in Alma-Ata continued 3 days and were tough because of unwillingness of leader of Three Districts Ehmetjan Qasimi (who was opposed in his decision by at least 2 members of Three Districts-Abdulkerim Abbas and Luo Zhi) to agree to incorporate the Three Districts into future Chinese communist state, supposedly in 1951 (People's Republic of China was proclaimed 2 years earlier, on October 1, 1949, mostly due to successful testing of atomic weapon by USSR on August 29, 1949, which stripped off the monopoly of USA for this weapon of mass destruction, after this testing Stalin pressed Mao to accelerate the term of Proclamation of PRC). He regarded the current situation as a real chance for centuries for Uyghurs and other people of all Xinjiang to gain freedom and independence, that shouldn't be lost. So, the Three Districts delegation was offered to continue negotiations in Moscow directly with Stalin before departure to Beijing. On August 24, Ehmetjan Qasimi, Abdulkerim Abbas, Ishaq Beg, Luo Zhi, Dalelkhan Sugirbayev and accompanied officers of the Three Districts, total 11 members of delegation, boarded a plane in Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, headed officially for Beijing, but flight was diverted for Moscow. On September 3, the Soviet Union informed the Chinese government that the plane had crashed near lake of Baikal en route to Beijing, killing all on board. On the same day Molotov sent telegram to Ghulja to inform Saifuddin Azizi (now the person in charge of the Three Districts when Ehmetjan Qasimi was not in Ili, and a member of Communist Party of Soviet Union) about Tragic death of devoted revolutionaries, including Ehmetjan Qasimi, in airplane crash near lake Baikal en route to Beijing. In accordance with instructions from Moscow, Saifuddin Azizi kept these tragic news secret from the population of East Turkestan Republic till the beginning of December 1949, when bodies of the Three Districts leaders were delivered from USSR ( already in the state out of recognition) and when People's Liberation Army of China secured already most of the regions of the former Xinjiang Province.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, some former KGB generals and high officers (among them Pavel Sudoplatov) revealed that five top leaders were killed on Stalin's orders in Moscow on August 27, 1949, after a three-day imprisonment in former Tsar's stables, being arrested just upon arrival at Moscow by the Head of MGB Colonel General Viktor Abakumov, who personally interrogated the Three Districts leaders, then ordered execution. This was allegedly done in accordance with a deal between Stalin and China's communist leader Mao Zedong,[72][73] but this allegation has never been confirmed. The remaining important figures of the Three Districts, including Saifuddin Azizi (who lead the Second delegation of the Three Districts, which participated in Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in September in Beijing, that proclaimed People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949), agreed to incorporate the Three Districts into the Xinjiang Province and accept important positions within the administration. However, some Kazakhs led by Osman Batur continued their resistance until 1954.[74][75] Saifuddin then became the first chairman of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which replaced Xinjiang Province in 1955. First People's Liberation Army units arrived at Urumchi airport on October 20, 1949 on Soviet airplanes, provided by Stalin, and quickly established control in Northern Xinjiang, then together with units of National Army of the Three Districts entered Southern Xinjiang, thus establishing control over all 10 districts of Xinjiang Province. Earlier, on September 26, 1949, 100,000 Kuomintang Army troops in the province within one day switched their allegiance from Kuomintang to Communist Party of China together with the Chairman of Xinjang Provincial Government Burhan Shahidi, who was among a few persons, who knew what actually happened with the First delegation of the Three Districts in August in the USSR. On December 20, 1949 National Army joined PLA as its 5th Army, with final political solution in the province solving in 1955, reorganizing it into autonomous region for 13 nationalities of Xinjiang.

National army

The National Army of the Second East Turkestan Republic was formed on April 8, 1945, and originally consisted of six regiments:

- Suidun infantry regiment

- Ghulja regiment

- Kensai regiment

- Ghulja reserve regiment

- Kazakh cavalry regiment

- Tungan regiment

- Sibo battalion

- Mongol battalion

General conscription of all races, except the Chinese, into National Army was enforced in the Ili zone.[49]

Later, Sibo and Mongol battalions were upgraded to regiments. When Kazakh irregulars under Osman Batur defected to the Kuomintang in 1947, the Kazakh cavalry regiment of National Army also defected to Osman Batur. The motorized part of Army consisted of an Artillery Division, which included twelve cannons, two armoured vehicles, and two tanks. National aviation forces included forty two airplanes, captured on Kuomintang air base in Ghulja on January 31, 1945, all of them were damaged during battle for air base. Some of these aircraft were repaired and put into service by Soviet military personnel in ETR. These airplanes participated in the battle between Ili rebels and the Kuomintang for Shihezi and Jinghe in September 1945.

This battle resulted in capturing of both KMT bases and oil fields in Dushanzi. During the battle one more Kuomintang air plane was captured, detachments of National Army reached Manasi River north of Urumchi, which caused panic in the city. Government offices were evacuated to Kumul. An offensive on Xinjiang's capital was cancelled due to direct pressure from Moscow on Ili rebels' leadership, which agreed to follow orders from Moscow to begin peace talks with Kuomintang. Moscow ordered the National Army to cease fire on all frontiers. First peace talks between Ili rebels and Kuomintang followed Chiang Kai-shek's speech on China State Radio, offering "to peacefully resolve Xinjiang crisis" with the rebels. These peace talks were mediated by the Soviet Union and started in Urumchi on October 14, 1945.

The National Army enlisted 25,000 to 30,000 troops. In accordance with the peace agreement with Chiang Kai-shek signed on June 6, 1946, this number was reduced to 11,000 to 12,000 troops and restricted to stations in only the Three Districts (Ili, Tarbaghatai and Altai) of Northern Xinjiang. The detachments of National Army were also withdrawn from Southern Xinjiang, leaving the strategic Old City of Aksu and opening the road from Urumchi to Kashgar Region. This gave the Kuomintang the opportunity to send 70,000 troops from 1946 to 1947 and quell Rebellion in Pamir Mountains.

This rebellion was broken on August 19, 1945, in the Sariqol area of Taghdumbash Pamir. Rebels under leadership of Uyghur Sadiq Khan Khoja from Kargilik and Sariqoli Tajik Karavan Shah captured all boundary posts near the Afghanistan, Soviet and Indian frontiers (Su-Bashi, Daftar, Mintaka Qarawul, Bulunqul), and a Tashkurgan fortress, killing Kuomintang troops. The rebels took Kuomintang troops by surprise as they celebrated the capitulation of Japanese Army in Manchuria. Few Kuomintang forces in Sariqol survived and fled to India during the rebel attack. The original base of the rebellion was situated on the mountainous Pamir village of Tagarma, close to the Soviet border. On September 15, 1945, Tashkurgan rebels took Igiz-Yar on the road to Yangihissar, while another group of rebels simultaneously took Oitagh, Bostan-Terek, and Tashmalik on the road to Kashgar.

By the end of 1945, Tashkurgan rebels launched an offensive on Kashgar and Yarkand districts. On January 2, 1946, while the Preliminary Peace Agreement was signed in Urumchi between Ili rebels and Kuomintang representatives under Soviet mediation, rebels took Guma, Kargilik, and Poskam, important towns controlling communications between Xinjiang, Tibet, and India. On January 11, 1946, the Kuomintang Army launched a counter-attack in the Yarkand military zone, bringing reinforcements from Aksu Region. The counter-attackers repelled Tashkurgan rebels from outskirts of Yarkand, recaptured towns Poskam, Kargilik, Guma and brought the Tashkurgan Region back under Chinese control by the summer of 1946.

Only a few hundred of the 7000 rebel forces survived. The survivors retreated to the mountainous Pamir base in Qosrap (village in present-day Akto County of XUAR). The National Army was inactive from 1946 to 1949 until the arrival of People's Liberation Army (PLA) units to Xinjiang.

Deng Liqun, a special envoy of Mao Zedong, arrived at Ghulja on August 17, 1949, to perform negotiations with the Three Districts leadership about future of the Three Districts. Deng sent a secret telegram to Mao about the Three Districts forces following day. He listed these forces as including about 14,000 troops, armed mostly by German weapons, heavy artillery weaponry, 120 military trucks and artillery towing vehicles, and around 6,000 cavalry horses. Soviet military personnel were present in the Army and serviced fourteen airplanes, which were used as air bombers. On December 20, 1949, the National Army was incorporated into the PLA as its Xinjiang 5th Army Corps.

Press

The newspaper of East Turkestan was Azat Sherkiy Turkistan (Free Eastern Turkestan), first published on November 17, 1944, in Ghulja five days after establishing of Second ETR Government. The newspaper was later renamed as Inqlawiy Sherkiy Turkistan (Revolutionary Eastern Turkestan).

Related events and people

According to her autobiography, Dragon Fighter: One Woman's Epic Struggle for Peace with China, Rebiya Kadeer's father served with pro-Soviet Uyghur rebels under the Second East Turkestan Republic in the Ili Rebellion (Three Province Rebellion) in 1944-1946, using Soviet assistance and aid to fight the Republic of China government under Chiang Kai-shek.[76] Kadeer and her family were close friends with White Russian exiles living in Xinjiang and Kadeer recalled that many Uyghurs thought Russian culture was "more advanced" than that of the Uyghurs and they "respected" the Russians a lot.[77]

In the Xinjiang conflict, the Soviet Union again backed Uyghur separatists against China starting in the 1960s. The Soviet Union incited separatist activities in Xinjiang through propaganda, encouraging Kazakhs to flee to the Soviet Union and attacking China. China responded by reinforcing the Xinjiang-Soviet border area specifically with Han Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps ("Bingtuan" in Chinese) militia and farmers.[78] The Soviets massively intensified their broadcasts inciting Uyghurs to revolt against the Chinese via Radio Tashkent since 1967 and directly harbored and supported separatist guerilla fighters to attack the Chinese border, in 1966 the amount of Soviet sponsored separatist attacks on China numbered 5,000.[79] The Soviets transmitted a radio broadcast from Radio Tashkent into Xinjiang on 14 May 1967, boasting of the fact that the Soviets had supported the Second East Turkestan Republic against China.[25] In addition to Radio Tashkent, other Soviet media outlets aimed at disseminating propaganda towards Uyghurs urging that they proclaim independence and revolt against China included Radio Alma-Ata and the Alma-Ata published Sherki Türkistan Evazi ("The Voice of Eastern Turkestan") newspaper.[80] After the Sino-Soviet split in 1962, over 60,000 Uyghurs and Kazakhs defected from Xinjiang to the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, in response to Soviet propaganda which promised Xinjiang independence. Uyghur exiles later threatened China with rumors of a Uyghur "liberation army" in the thousands that were supposedly recruited from Sovietized emigres.[81]

The Soviet Union was involved in funding and support to the East Turkestan People's Revolutionary Party (ETPRP), the largest militant Uyghur separatist organization in its time, to start a violent uprising against China in 1968.[82][83][84][85][86] In the 1970s, the Soviets also supported the United Revolutionary Front of East Turkestan (URFET) to fight against the Chinese.[87]

"Bloody incidents" in 1966-67 flared up as Chinese and Soviet forces clashed along the border as the Soviets trained anti-Chinese guerillas and urged Uyghurs to revolt against China, hailing their "national liberation struggle".[88] In 1969, Chinese and Soviet forces directly fought each other along the Xinjiang-Soviet border.[89][90][91][92]

The Soviet Union supported Uyghur nationalist propaganda and Uyghur separatist movements against China. The Soviet historians claimed that the Uyghur native land was Xinjiang and Uyghur nationalism was promoted by Soviet versions of history on turcology.[93] Soviet turcologists like D.I. Tikhonov wrote pro-independence works on Uyghur history and the Soviet supported Uyghur historian Tursun Rakhimov wrote more historical works supporting Uyghur independence and attacking the Chinese government, claiming that Xinjiang was an entity created by China made out of the different parts of East Turkestan and Zungharia.[94] These Soviet Uyghur historians were waging an "ideological war" against China, emphasizing the "national liberation movement" of Uyghurs throughout history.[95] The Soviet Communist Party supported the publication of works which glorified the Second East Turkestan Republic and the Ili Rebellion against China in its anti-China propaganda war.[96] Soviet propaganda writers wrote works claiming that Uyghurs lived better lives and were able to practice their culture only in Soviet Central Asia and not in Xinjiang.[97] In 1979 Soviet KGB agent Victor Louis wrote a thesis claiming that the Soviets should support a "war of liberation" against the "imperial" China to support Uighur, Tibetan, Mongol, and Manchu independence.[98][99] The Soviet KGB itself supported Uyghur separatists against China.[100]

Uyghur nationalist historian Turghun Almas and his book Uyghurlar (The Uyghurs) and Uyghur nationalist accounts of history were galvanized by Soviet stances on history, "firmly grounded" in Soviet Turcological works, and both heavily influenced and partially created by Soviet historians and Soviet works on Turkic peoples.[101] Soviet historiography spawned the rendering of Uyghur history found in Uyghurlar.[102] Almas claimed that Central Asia was "the motherland of the Uyghurs" and also the "ancient golden cradle of world culture".[103]

Xinjiang's importance to China increased after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, leading to China's perception of being encircled by the Soviets.[104] The China supported the Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet invasion, and broadcast reports of Soviet atrocities on Afghan Muslims to Uyghurs in order to counter Soviet propaganda broadcasts into Xinjiang, which boasted that Soviet minorities lived better and incited Muslims to revolt.[105] Chinese radio beamed anti-Soviet broadcasts to Central Asian ethnic minorities like the Kazakhs.[89] The Soviets feared disloyalty among the non-Russian Kazakh, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz in the event of Chinese troops attacking the Soviet Union and entering Central Asia. Russians were goaded with the taunt "Just wait till the Chinese get here, they'll show you what's what!" by Central Asians when they had altercations.[106] The Chinese authorities viewed the Han migrants in Xinjiang as vital to defending the area against the Soviet Union.[107] China opened up camps to train the Afghan Mujahideen near Kashgar and Khotan and supplied them with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of small arms, rockets, mines, and anti-tank weapons.[108][109]

Similar Soviet supported states

The Soviet Union set up a similar puppet state in Pahlavi dynasty Iran in the form of the Azerbaijan People's Government and Republic of Mahabad[110] The Soviet Union used comparable methods and tactics in both Xinjiang and Iran when they established the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad and Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan.[111] The American Ambassador to the Soviet Union sent a telegram back to Washington DC in which he said that the situation in Iranian Azerbaijan and in Xinjiang were similar.[112]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Besides original 15 Soviet Republics of the Soviet Union, Sheng Shicai considered Mongolia as 16th Soviet Republic and Tuva, whose incorporation into USSR was under way, as 17th Soviet Republic.

References

Citations

- ↑ David D. Wang. Under the Soviet Shadow: The Yining Incident; Ethnic Conflicts and International Rivalry in Xinjiang, 1944–1949. pg. 406

- 1 2 http://www.oxuscom.com/sovinxj.htm

- ↑ David Wang. The Xinjiang question of the 1940s: the story behind the Sino-Soviet treaty of August 1945

- ↑ Into Tibet: Thomas Laird. The CIA's First Atomic Spy and His Secret Expedition to Lhasa pg. 25

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 176

- ↑ Forbes (1986), pp. 178–179

- ↑ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volumes 276-278. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Agreement of Concessions, Article 7.

- ↑ Lin 2007, p. 130. Archived September 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lin 2002.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), pp. 172–173

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 174

- ↑ Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs 1982, p. 299.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), pp. 176

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 178

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 180

- 1 2 Forbes (1986), p. 181

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 179

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 183

- 1 2 Forbes (1986), p. 184

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 217

- ↑ Forbes (1986), pp. 185–186

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 187

- 1 2 Forbes (1986), p. 188

- ↑ Potter 1945, "Red Troops Reported Aiding Sinkiang Rebels Fight China" p. 2

- 1 2 Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES 1945, "Sinkiang Truce Follows Bombings Of Chinese in 'Far West' Revolt; Chungking General Negotiates With Moslem Kazakhs--Red-Star Planes Are Traced to Earlier Soviet Supply in Area" p. 2

- ↑ Shipton, Eric (1997). The Six Mountain-travel Books. The Mountaineers Books. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-89886-539-4.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 204

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 576

- ↑ Preston & Partridge & Best 2000, p. 63

- ↑ Jarman 2001, p. 217.

- ↑ Preston & Partridge & Best 2003, p. 25

- ↑

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 168

- ↑ 1949, "The Sydney Morning Herald " p. 4

- ↑ Wang 1999, p. 373.

- ↑ Ammentorp 2000–2009, "Generals from China Ma Chengxiang"

- ↑ Brown & Pickowicz 2007, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 厉声 (2003) 204-206.

- ↑ 徐玉圻 (1998) 132.

- 1 2 3 4 徐玉圻 (1998) 171-174.

- 1 2 Perkins (1947), pp. 548–549

- 1 2 3 Perkins (1947), pp. 554, 556-557

- ↑ 厉声 (2003) 208-210.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 217

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 191

- ↑ Jeremy Brown; Paul Pickowicz (2007). Dilemmas of Victory: The Early Years of the People's Republic of China. Harvard University Press. pp. 188–. ISBN 978-0-674-02616-2.

- 1 2 Perkins (1947)

- ↑ Kamalov, Ablet (2010). Millward, James A.; Shinmen, Yasushi; Sugawara, Jun, eds. Uyghur Memoir literature in Central Asia on Eastern Turkistan Republic (1944-49). Studies on Xinjiang Historical Sources in 17-20th Centuries. Tokyo: The Toyo Bunko. p. 260.

- ↑ Ondřej Klimeš (8 January 2015). Struggle by the Pen: The Uyghur Discourse of Nation and National Interest, c.1900-1949. BRILL. pp. 241–. ISBN 978-90-04-28809-6.

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 557

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 580

- ↑ Clark, William (2011). "Ibrahim's story" (PDF). Asian Ethnicity. Taylor & Francis. 12 (2): 213. doi:10.1080/14631369.2010.510877. ISSN 1463-1369. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 571

- ↑ Royal Central Asian Society, London (1949). Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society. Royal Central Asian Society. p. 71.

- ↑ Perkins (1947), pp. 572-573

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 578

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 579

- ↑ Li, Chang. "The Soviet Grip on Sinkaing". Foreign Affairs. 32 (3): 491–503. JSTOR 20031047.

- ↑ Taylor & Francis. China and the Soviet Union. p. 233. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 215

- ↑ "Political Implications in Mongolian Invasion of N. China Province". The Canberra Times. 13 June 1947.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), p. 214

- ↑ Dickens, Mark. "The Soviets in Xinjiang 1911–1949". Oxus Communications. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ "CHINESE TROOPS RECAPTURE PEITASHAN". The Canberra Times. 13 June 1947.

- ↑ David D. Wang (1999). Clouds over Tianshan: essays on social disturbance in Xinjiang in the 1940s. NIAS Press. p. 87. ISBN 87-87062-62-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Xiaoyuan Liu (2006). Reins of liberation: an entangled history of Mongolian independence, Chinese territoriality, and great power hegemony, 1911–1950. Stanford University Press. p. 380. ISBN 0-8047-5426-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "CHINA: Encirclement". TIME magazine. 6 October 1947.

- ↑ "A Letter From The Publisher, Oct. 20, 1947". TIME magazine. 20 October 1947.

- ↑ David D. Wang (1999). Under the Soviet shadow: the Yining Incident : ethnic conflicts and international rivalry in Xinjiang, 1944–1949. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press. pp. 275, 301, 302. ISBN 962-201-831-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ A brief introduction of Uyghur history Birkbeck, University of London

- ↑ The quest for an eighth Turkic nation Taipei Times

- ↑ Xinjiang by S. Frederick Starr

- ↑ Sinkiang and Sino-Soviet Relations

- ↑ Kadeer 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ Kadeer 2009, p. 13.

- ↑ Starr 2004, p. 138.

- ↑ Starr 2004, p. 139.

- ↑ Dickens, 1990.

- ↑ Bovingdon 2010, pp. 141–142

- ↑ Dillon 2003, p. 57.

- ↑ Clarke 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ Dillon 2008, p. 147.

- ↑ Nathan 2008,.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=etRkjLv8AosC&pg=PT278&dq=soviet+turkestan+people's+party&hl=en&sa=X&ei=dpQcU9iPN-fN0wHUrYCYAQ&ved=0CFEQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=soviet%20turkestan%20people's%20party&f=false

- ↑ Reed 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ Ryan 1969, p. 3.

- 1 2 Tinibai 2010, Bloomberg Businessweek p. 1 Archived July 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Tinibai 2010, gazeta.kz.

- ↑ Tinibai 2010, Transitions Online.

- ↑ Burns, 1983.

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 37

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 38

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 39

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 40

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 41

- ↑ Wong 2002, p. 172.

- ↑ Liew 2004, p. 175.

- ↑ Wang 2008, p. 240.

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 42

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 33

- ↑ Bellér-Hann (2007), p. 4

- ↑ Clarke 2011, p. 76.

- ↑ Radio war aims at China Moslems 1981, p. 11.

- ↑ Meehan 1980.

- ↑ Clarke 2011, p. 78.

- ↑ Starr 2004, p. 149.

- ↑ Starr 2004, p. 158.

- ↑ Forbes (1986), pp. 177–

- ↑ Forbes (1986), pp. 261–263

- ↑ Perkins (1947), p. 550

Sources

- Ammentorp, Steen (2000–2009). "The Generals of WWII Generals from China Ma Chengxiang". Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó, ed. (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0754670414. ISSN 1759-5290.

- Benson, Linda (1990). The Ili Rebellion: the Moslem challenge to Chinese authority in Xinjiang, 1944-1949. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-87332-509-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Bovingdon, Gardner (2010), The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231519419

- Brown, Jeremy; Pickowicz, Paul (2007). Dilemmas of victory: the early years of the People's Republic of China. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02616-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Burhan S., Xinjiang wushi nian [Fifty Years in Xinjiang], (Beijing, Wenshi ziliao, 1984).

- Burns, John F. (July 6, 1983). "ON SOVIET-CHINA BORDER, THE THAW IS JUST A TRICKLE". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Chen, Jack (1977). The Sinkiang story. Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-524640-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Clarke, Michael E. (2011). Xinjiang and China's Rise in Central Asia - A History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1136827064. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Clubb, O. E., China and Russia: The 'Great Game’. (NY, Columbia, 1971).

- Dickens, Mark (1990). "The Soviets in Xinjiang 1911-1949". OXUS COMMUNICATIONS. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Dillon, Michael (2008). Contemporary China - An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 1134290543. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dillon, Michael (2003). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Far Northwest. Routledge. ISBN 1134360967. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521255147.

- Hasiotis, A. C. Jr. Soviet Political, Economic and Military Involvement in Sinkiang from 1928 to 1949 (NY, Garland, 1987).

- Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs (1982). Journal of the Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, Volumes 4-5. King Abdulaziz University. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Jarman, Robert L., ed. (2001). China political reports 1911-1960, Volume 8. Archive Editions. ISBN 1852079304. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kadeer, Rebiya (2009). Dragon Fighter: One Woman's Epic Struggle for Peace with China. Alexandra Cavelius (illustrated ed.). Kales Press. ISBN 0979845610. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Khakimbaev A. A., 'Nekotorye Osobennosti Natsional’no-Osvoboditel’nogo Dvizheniya Narodov Sin’tszyana v 30-kh i 40-kh godakh XX veka' [Some Characters of the National-Liberation Movement of the Xinjiang Peoples in 1930s and 1940s], in Materially Mezhdunarodnoi Konferentsii po Problemam Istorii Kitaya v Noveishchee Vremya, Aprel’ 1977, Problemy Kitaya (Moscow, 1978) pp. 113–118.

- Kotov, K. F., Mestnaya Natsional'nya Avtonomiya v Kitaiskoi Narodnoi Respublike—Na Primere Sin'tszyansko-Uigurskoi Avtonomoi Oblasti, [Autonomy of Local Nationalities in the Chinese People's Republic, as an Example of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region], (Moscow, Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel’stvo Yuridichekoi Literaturi, 1959).

- Kutlukov, M., 'Natsionlal’no-Osvoboditel’noe Dvizhenie 1944–1949 gg. v Sin’tszyane kak Sostavnaya Chast’ Kitaiskoi Narodnoi Revolyutsii', [The National-Liberation Movement of 1944–1949 in Xinjiang as a Part of the People’s Revolution in China], in Sbornik Pabot Aspirantov, Otdelenie Obshchestvennykh Hauk, AN UzbSSR, Bypusk 2 (Tashkent, 1958) pp. 261–304.

- Lattimore, O., Pivot of Asia: Sinkiang and the Inner Asian Frontiers of China (Boston, Little, Brown & Co., 1950).

- Liew, Leong H.; Wang, Shaoguang, eds. (2004). Nationalism, Democracy and National Integration in China. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0203404297. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Lin, Hsiao-ting (December 2002). "Between Rhetoric and Reality: Nationalist China's Tibetan Agenda during the Second World War (1)". Canadian Journal of History. Gale, Cengage Learning. 37 (No. 3). Archived from the original on December 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Lin, Hsiao-ting (2007). "Nationalists, Muslim Warlords, and the "Great Northwestern Development" in Pre-Communist China" (PDF). China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program. 5 (No. 1): 115–135. ISSN 1653-4212. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Meehan, Lieutenant Colonel Dallace L. (May–June 1980). "Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Military implications for the decades ahead". Air University Review. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231139241. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Mingulov, N. N., 'Narody Sin’tszyana v Bop’be za Ustanovlenue Harodnoi Demokratii 1944–1949 gg.', [The Xinjiang Peoples in Struggle for Establishment of People’s Democracy, 1944–1949], (Abstract of Dissertation in Moscow National University, 1956).

- Nathan, Andrew James; Scobell, Andrew (2013). China's Search for Security (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231511647. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- 'Natsionlal’no-Osvoboditel’noe Dvizhenie Narodov Sin’tszyana kak Sostavnaya Chast’ * Obshchekitaiskoi Revolyutsii (1944–1949 gody)', [The National-Liberation Movement of the Peoples in Xinjiang in 1944–1949 as a Part of the People’s Revolution in China], in Trudi: Instituta Istorii, Arkheologii i Etnografii, Tom 15 (Alma-Ata, 1962) pp. 68–102.

- Perkins, E. Ralph, ed. (1947). "Unsuccessful attempts to resolve political problems in Sinkiang; extent of Soviet aid and encouragement to rebel groups in Sinkiang; border incident at Peitashan". The Far East: China (PDF). Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947. VII. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 546–587. Documents 450–495.

- Preston, Paul; Partridge, Michael; Best, Antony (2000). British Documents on Foreign Affairs--reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: Far Eastern affairs, July-December 1946. Volume 2 of British Documents on Foreign Affairs--reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: From 1946 Through 1950. Asia 1946. University Publications of America. ISBN 1-55655-768-X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Preston, Paul; Partridge, Michael; Best, Antony (2003). British Documents on Foreign Affairs--reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: French Indo-China, China, Japan, Korea and Siam, January 1949-December 1949. Volume 8 of British Documents on Foreign Affairs--reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: From 1946 Through 1950. Asia 1946, British Documents on Foreign Affairs--reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: From 1946 Through 1950. Asia 1946. University Publications of America. ISBN 155655768X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Potter, Philip (22 Oct 1945). "Red Troops Reported Aiding Sinkiang Rebels Fight China". The Sun (1837-1988) - Baltimore, Md. p. 2.

- Rakhimov, T. R. 'Mesto Bostochno-Turkestanskoi Respubliki (VTR) v Natsional’no-Osvoboditel’noi Bor’be Narodov Kitaya' [Role of the Eastern Turkestan Republic (ETR) in the National Liberation Struggle of the Peoples in China], A paper presented at 2-ya Nauchnaya Konferentsiya po Problemam Istorii Kitaya v Noveishchee Vremya, (Moscow, 1977), pp. 68–70.

- Reed, J. Todd; Raschke, Diana (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0313365407. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Royal Central Asian Society, London (1949). Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, Volumes 36-38. Royal Central Asian Society. Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- Royal Central Asian Society (1949). Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, Volume 36. Royal Central Asian Society. Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- RYAN, WILLIAM L. (Jan 2, 1969). "Russians Back Revolution in Province Inside China". The Lewiston Daily Sun. p. 3. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Saviskii, A. P. 'Sin’tszyan kak Platsdarm Inostrannoi Interventsii v Srednei Azii', [Xinjiang as a Base for Foreign Invasion into Central Asia], (Abstract of Dissertation in the Academy of Science, the Uzbekistan SSR), (AN UzbSSR, Tashkent, 1955).

- Shipton, Eric; Perrin, Jim (1997). Eric Shipton: The Six Mountain-Travel Books. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-539-5. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Taipov, Z. T., V Bor'be za Svobodu [In the Struggle for Freedom], (Moscow, Glavnaya Redaktsiya Vostochnoi Literaturi Izdatel'stvo Nauka, 1974).

- Tinibai, Kenjali (May 28, 2010). "China and Kazakhstan: A Two-Way Street". Bloomberg Businessweek. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (2010-05-28). "Kazakhstan and China: A Two-Way Street". Gazeta.kz. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (27 May 2010). "Kazakhstan and China: A Two-Way Street". Transitions Online. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Wang, D., 'The Xinjiang Question of the 1940s: the Story behind the Sino-Soviet Treaty of August 1945', Asian Studies Review, vol. 21, no.1 (1997) pp. 83–105.

- Wang, David D. (1999). Under the Soviet shadow: the Yining Incident : ethnic conflicts and international rivalry in Xinjiang, 1944-1949. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press. ISBN 962-201-831-9. Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- Wang, Gungwu; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2008). China and the New International Order (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0203932269. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Wayne, Martin I. (2007). China's War on Terrorism: Counter-Insurgency, Politics and Internal Security. Routledge. ISBN 1134106238. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wong, John; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2002). China's Post-Jiang Leadership Succession: Problems and Perspectives. World Scientific. ISBN 981270650X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- 'The USSR and the Establishment of the Eastern Turkestan Republic in Xinjiang', Journal of Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, vol.25 (1996) pp. 337–378.

- Yakovlev, A. G., 'K Voprosy o Natsional’no-Osvoboditel’nom Dvizhenii Norodov Sin’tzyana v 1944–1949', [Question on the National Liberation Movement of the Peoples in Xinjiang in 1944–1945], in Uchenie Zapiski Instituta Voctokovedeniia Kitaiskii Spornik vol.xi, (1955) pp. 155–188.

- Wang, David D. Under the Soviet shadow: the Yining Incident: ethnic conflicts and international rivalry in Xinjiang, 1944–1949. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1999.

- Wang, David D.《Clouds over Tianshan: essays on social disturbance in Xinjiang in the 1940s》Copenhagen: NIAS, 1999.

- Benson, Linda, The Ili Rebellion: The Moslem challenge to Chinese authority in Xinjiang, 1944–1949, Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1990. ISBN 0-87332-509-5.

- James A. Millward and Nabijan Tursun, "Political History and Strategies of Control, 1884–1978" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2.

- Wireless to THE NEW YORK TIMES (22 October 1945). "Sinkiang Truce Follows Bombings Of Chinese in 'Far West' Revolt; Chungking General Negotiates With Moslem Kazakhs--Red-Star Planes Are Traced to Earlier Soviet Supply in Area". THE NEW YORK TIMES. p. 2.

- "New Republic". The Sydney Morning Herald. Oct 2, 1949. p. 4.

- UPI (Sep 22, 1981). "Radio war aims at China Moslems". The Montreal Gazette. p. 11. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- 徐玉圻 主编, 《新疆三区革命史》, 民族出版社, 1998.

- 厉声 主编, 《中国新疆历史与现状》, 人民出版社, 2003.