Pacification of Libya

| Pacification of Libya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Interwar Period | |||||||

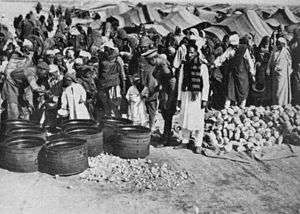

Cyrenaican rebel leader Omar Mukhtar (the man in robes with a chain on his left arm) after his arrest by Italian armed forces in 1931. Mukhtar was executed in a public hanging shortly afterward. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Over 80,000 Cyrenaicans killed[3] | |||||||

The Pacification of Libya, also known as the Second Italo-Senussi War, was a prolonged conflict in Italian Libya between Italian military forces and indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi Order that lasted from 1923 until 1932,[4][5] when the principal Senussi leader, Omar Mukhtar, was captured and executed.[6]

The pacification resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in Cyrenaica - one quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000 people died during the conflict.[3] Italy committed major war crimes during the conflict; including the use of chemical weapons, episodes of refusing to take prisoners of war and instead executing surrendering combatants, and mass executions of civilians.[2] Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing by forcibly expelling 100,000 Bedouin Cyrenaicans, half the population of Cyrenaica, from their settlements that was slated to be given to Italian settlers.[1][7]

In 2008, an agreement of compensation for damages caused by Italian colonial rule was signed between Italy and Libya. Muammar Gaddafi, Libyan ruler at the time, attended the signing ceremony of the document wearing a historical photograph on his uniform that shows Cyrenaican rebel leader Omar Mukhtar in chains after being captured by Italian authorities during the Pacification. At the signing ceremony of the document, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi declared: "In this historic document, Italy apologizes for its killing, destruction and repression of the Libyan people during the period of colonial rule." and went on to say that this was a "complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era".[8]

Background

After Italy had conquered Libya from the Ottoman Empire in 1912, the new colony shortly broke out into revolt, with Italian authorities losing control over large regions of the colony.[9] Italy had been in near-constant conflict with the Senussis since Italy seized control of Libya from the Ottoman Empire. Conflict between Italy and the Senussis erupted into major violence during World War I when the Senussis in Libya collaborated with the Ottoman Empire against Italy and rading into Egypt to attack British forces, to assist Turkish forces attacking the British from the Levant.[10] Warfare between the British versus the Senussis continued until 1917 when the Senussis made peace with the British.[11]

In 1917, Italy signed the Treaty of Acroma that acknowledged effective virtual independence of Libya from direct Italian control.[12] In 1918, Tripolitanian rebels founded the Tripolitanian Republic.[13]

In 1920, the Italian government attempted to reach a settlement with the Senussi in Cyrenaica and recognized Senussi leader Sayid Idris as Emir of Cyrenaica and granted Cyrenaica autonomy under Italian rule.[14] In 1922 Tripolitanian leaders offered Idris the position of Emir of Tripolitania.[15] However prior to Idris being able to accept the position, the Italian government decided to initiate a campaign of reconquest of Libya.[16]

The rise to power of Benito Mussolini as Prime Minister of Italy and his National Fascist Party resulted in a change in foreign policy that resulted in the Pacification of Libya.[17]

From 1923 to 1924, Italian military forces regained all territory north of the Ghadames-Mizda-Beni Ulid region, with four fifths of the estimated population of Tripolitania and Fezzan within the Italian area; and Italian forces had regained the northern lowlands of Cyrenaica in during these two years.[17] However attempts by Italian forces to occupy the forest hills of Jebel Akhtar were met with popular guerrilla resistance. This resistance was led by Senussi sheikh Omar Mukhtar.[17]

The Pacification

The Pacification began in 1928 with Italian forces rapidly occupied the Sirte desert separating Tripolitania from Cyrenaica, utilizing aircraft, motor transport, and good logistical organization that allowed the Italians to occupy 150,000 square kilometres of territory in five months.[18] By doing this, the Italians cut off the physical connection formerly held by the rebels between Cyrenaica and Tripolitania.[18] By late 1928, the Italians took control of Ghibla and its tribes were disarmed.[18]

Attempted negotiations between Italy and Omar Mukhtar broke down during the summer of 1929 and Italy then planned for the complete conquest of Libya from the rebels.[19] In 1930, Italian forces conquered Fezzan and rose the Italian flag in Tummo, the southernmost region of Fezzan.[18]

12,000 Cyrenaicans were executed from 1930 to 1931 and all the nomadic peoples of northern Cyrenaica were forcefully removed from the region and relocated to huge concentration camps in the Cyrenaican lowlands.[19] In June 1930, Italian military authorities carried out the forced migration and deportation of the entire population of Jebel Akhdar in Cyrenaica, resulting in 100,000 Bedouins, half the population of Cyrenaica, being expelled from their settlements.[7] These 100,000 people who were mostly women, children, and the elderly, were forced by Italian authorities to march across the desert to a series of barbed-wire concentration camp compounds erected near Benghazi, any stragglers who could not keep up with the march were summarily shot by Italian authorities.[20] Propaganda by the Fascist regime declared the camps to be oases of modern civilization that were hygienic and efficiently run - however in reality the camps had poor sanitary conditions as the camps had an average of about 20,000 Beduoins together with their camels and other animals, crowded into an area of one square kilometre.[20] The camps held only rudimentary medical services, with the camps of Soluch and Sisi Ahmed el Magrun with 33,000 internees each having only one doctor between them.[20] Typhus and other diseases spread rapidly in the camps as the people were physically weakened by meagre food rations provided to them and forced labour.[20] By the time the camps closed in September 1933, 40,000 of the 100,000 total internees had died in the camps.[20]

To close rebel supply routes from Egypt, the Italians constructed a 300-kilometre barbed wire fence on the border with Egypt that was patrolled by armoured cars and aircraft.[19] The Italians persecuted the Senussi Order: zawias were closed; mosques were closed and Senussi practices were forbidden; Senussi estates were confiscated; and preparations were made for Italian conquest of the Kufra Oasis, the last stronghold of the Senussi in Libya.[19] In January 1931, Italian forces seized Kufra where Senussi refugees were bombed and strafed by Italian aircraft as they fled into the desert.[19] Mukhtar was captured by the Italians in 1931 followed by a court martial and his public execution by hanging at Suluq.[19]

Mukhtar's death effectively ended the resistance, and in January 1932, Badoglio proclaimed the end of the Pacification of Libya.[22]

War crimes

Specific war crimes alleged to have been committed by the Italian armed forces against civilians include: deliberate bombing of civilians; killing unarmed children, women, and the elderly; rape and disembowelment of women; throwing prisoners out of aircraft to their death and running over others with tanks; regular daily executions of civilians in some areas; and bombing tribal villages with mustard gas bombs beginning in 1930.[23]

References

- 1 2 Cardoza, Anthony L. (2006). Benito Mussolini: the first fascist. Pearson Longman. p. 109.

- 1 2 Duggan, Christopher (2007). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 497.

- 1 2 Mann, Michael (2006). The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 309.

- ↑ Nina Consuelo Epton, Oasis Kingdom: The Libyan Story (New York: Roy Publishers, 1953), p. 126.

- ↑ C. C. Stewart, "Islam", The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7 : c. 1905 – c. 1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 196.

- ↑ Detailed description of some fights (in Italian)

- 1 2 Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 358.

- ↑ Oxford Business Group (2008). The Report: Libya 2008. p. 17.

- ↑ Wright, John (1983). Libya: A Modern History. Kent, England: Croom Helm. p. 30.

- ↑ Ian F. W. Beckett. The Great War: 1914-1918. Routledge, 2013. P188.

- ↑ Adrian Gilbert. Encyclopedia of Warfare: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Routledge, 2000. P221.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- ↑ Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- 1 2 3 Wright 1983, p. 33

- 1 2 3 4 Wright 1983, p. 34

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wright 1983, p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 5 Duggan 2007, p. 496

- ↑ David Miller, Chris Foss. Great Book of Tanks: The World's Most Important Tanks from World War I to the Present Day. Zenith Imprint, 2003. Pp. 83.

- ↑ Wright 1983, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Geoff Simons, Tam Dalyell (British Member of Parliament, forward introduction). Libya: the struggle for survival. St. Martin's Press, 1996. 1996 Pp. 129.