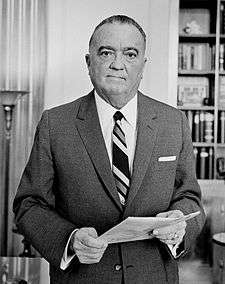

J. Edgar Hoover

| J. Edgar Hoover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation | |

|

In office March 23, 1935 – May 2, 1972 | |

| President |

Franklin Roosevelt Harry Truman Dwight Eisenhower John F. Kennedy Lyndon Johnson Richard Nixon |

| Deputy | Clyde Tolson |

| Preceded by | Himself (BOI Director) |

| Succeeded by | Pat Gray (Acting) |

| Director of the Bureau of Investigation | |

|

In office May 10, 1924 – March 22, 1935 | |

| President |

Calvin Coolidge Herbert Hoover Franklin Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | William J. Burns |

| Succeeded by | Himself (FBI Director) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Edgar Hoover January 1, 1895 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died |

May 2, 1972 (aged 77) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Congressional Cemetery |

| Alma mater | George Washington University (LLB, LLM) |

| Religion | Presbyterianism |

| Signature |

|

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) of the United States. He was appointed as the sixth director of the Bureau of Investigation—predecessor to the FBI—in 1924 and was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972, aged 77. Hoover is credited with building the FBI into a larger crime-fighting agency than it was at its inception and with instituting a number of modernizations to police technology, such as a centralized fingerprint file and forensic laboratories.

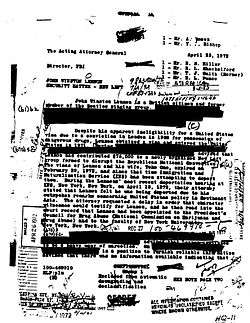

Later in life and after his death, Hoover became a controversial figure as evidence of his secretive abuses of power began to surface. He was found to have exceeded the jurisdiction of the FBI,[1] and to have used the FBI to harass political dissenters and activists, to amass secret files on political leaders,[2] and to collect evidence using illegal methods.[3] Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was in a position to intimidate and threaten sitting presidents.[4] According to biographer Kenneth Ackerman, the notion that Hoover's secret files kept presidents from firing him is a myth.[5] However, Richard Nixon was recorded as stating in 1971 that one of the reasons he did not fire Hoover was that he was afraid of reprisals against him from Hoover.[6]

According to President Harry S. Truman, Hoover transformed the FBI into his private secret police force. Truman stated: "we want no Gestapo or secret police. The FBI is tending in that direction. They are dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail. J. Edgar Hoover would give his right eye to take over, and all congressmen and senators are afraid of him."[7]

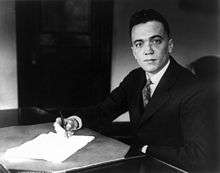

Early life and education

John Edgar Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie (née Scheitlin; 1860–1938), who was of Swiss-German descent, and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr. (1856–1921), who was of English and German ancestry. Hoover's maternal great-uncle, John Hitz, was a Swiss honorary consul general to the United States.[8] Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed upon his birth, although it was required in 1895 Washington. Two of his siblings had certificates, but Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.[8]

Hoover grew up near the Eastern Market, in Washington's Capitol Hill neighborhood, and attended Central High School, where he sang in the school choir, participated in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program, and competed on the debate team,[9] where he argued against women getting the right to vote and against the abolition of the death penalty.[10] The school newspaper applauded his "cool, relentless logic".[11] [12]

Hoover was a stutterer as a boy, which he overcame by teaching himself to talk fast—a style that he carried through his adult career. He eventually spoke with such ferocious speed that stenographers had a hard time following him.[13]

He obtained a Bachelor of Laws[14] from The George Washington University Law School in 1916, where he was a member of the Alpha Nu Chapter of the Kappa Alpha Order, and an LL.M., a Master of Laws degree, in 1917 from the same university.[15][16] While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock, the New York City United States Postal Inspector, who waged prolonged campaigns against fraud, vice, pornography, and birth control. Hoover lived in Washington, D.C. for his entire life.[11]

Hoover was 18 years old when he accepted his first job, an entry-level position as messenger in the orders department, at the Library of Congress. The library was a half mile from his house. The experience shaped both Hoover and the creation of the FBI profiles; as Hoover noted in a 1951 letter, "This job […] trained me in the value of collating material. It gave me an excellent foundation for my work in the FBI where it has been necessary to collate information and evidence."[17]

Department of Justice

Immediately after getting his LL.M. degree, Hoover was hired by the Justice Department to work in the War Emergency Division. He soon became the head of the Division's Alien Enemy Bureau, authorized by President Wilson at the beginning of World War I to arrest and jail disloyal foreigners without trial.[11] He received additional authority from the 1917 Espionage Act. Out of a list of 1,400 suspicious Germans living in the U.S., the Bureau arrested 98 and designated 1,172 as arrestable.[18]

In August 1919, Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division—also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.[18] America's First Red Scare was beginning, and one of Hoover's first assignments was to carry out the Palmer Raids.[19]

Hoover and his chosen assistant, George Ruch,[20] monitored a variety of U.S. radicals with the intent to punish, arrest, or deport those whose politics they decided were dangerous. Targets during this period included Marcus Garvey;[21] Rose Pastor Stokes and Cyril Briggs;[22] Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman;[23] and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, who, Hoover maintained, was "the most dangerous man in the United States".[24]

In 1921, Hoover rose in the Bureau of Investigation to deputy head and, in 1924, the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Hoover as the sixth Director of the Bureau of Investigation, partly in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal. When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents.

Hoover was sometimes unpredictable in his leadership. He frequently fired Bureau agents, singling out those he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers," or whom he considered "pinheads."[25] He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations; Melvin Purvis was a prime example. Purvis was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs, and it is alleged that Hoover maneuvered him out of the Bureau because Hoover was jealous of the substantial public recognition Purvis received.[26]

Hoover often hailed local law-enforcement officers around the country, and built up a national network of supporters and admirers in the process. One whom he often commended for particular effectiveness was the conservative sheriff of Caddo Parish, Louisiana, J. Howell Flournoy.[27]

Gangster wars

In the early 1930s, criminal gangs carried out large numbers of bank robberies in the Midwest. They used their superior firepower and fast getaway cars to elude local law enforcement agencies and avoid arrest. Many of these criminals frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States, particularly John Dillinger, who became famous for leaping over bank cages, and repeatedly escaping from jails and police traps. The gangsters enjoyed a level of sympathy in the Midwest, as banks and bankers were widely seen as oppressors of common people during the Great Depression.

The robbers operated across state lines, and Hoover pressed to have their crimes recognized as federal offenses so that he and his men would have the authority to pursue them and get the credit for capturing them. Initially, the Bureau suffered some embarrassing foul-ups, in particular with Dillinger and his conspirators. A raid on a summer lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin, called "Little Bohemia", left a Bureau agent and a civilian bystander dead and others wounded; all the gangsters escaped. Hoover realized that his job was then on the line, and he pulled out all stops to capture the culprits. In late July 1934, Special Agent Melvin Purvis, the Director of Operations in the Chicago office, received a tip on Dillinger's whereabouts that paid off when Dillinger was located, ambushed, and killed by Bureau agents outside the Biograph Theater.[28]

In the same period, there were numerous Mafia shootings as a result of Prohibition, while Hoover continued to deny the very existence of organized crime.[29] Gangster Frank Costello helped encourage this view by feeding Hoover tips on sure winners through their mutual friend, gossip columnist Walter Winchell.[30] (Hoover had a reputation as "an inveterate horseplayer" known to send Special Agents to place $100 bets for him.)[30] Hoover said the Bureau had "much more important functions" than arresting bookmakers and gamblers.[30]

Hoover was credited with several highly publicized captures or shootings of outlaws and bank robbers, even though he was not present at the events. These included those of Machine Gun Kelly in 1933, of Dillinger in 1934, and of Alvin Karpis in 1936, which led to the Bureau's powers being broadened.

In 1935, the Bureau was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1939, the FBI became pre-eminent in the field of domestic intelligence, thanks in large part to changes made by Hoover, such as expanding and combining fingerprint files in the Identification Division, to compile the largest collection of fingerprints to date,[31][32] and Hoover's help to expand the FBI's recruitment and create the FBI Laboratory, a division established in 1932 to examine and analyze evidence found by the FBI.

Investigation of subversion and radicals

Hoover was concerned about what he claimed was subversion, and under his leadership, the FBI investigated tens of thousands of suspected subversives and radicals. According to critics, Hoover tended to exaggerate the dangers of these alleged subversives and many times overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.[33]

William G. Hundley, a Justice Department prosecutor, said Hoover may have inadvertently kept alive the concern over communist infiltration into the government because Hoover's "informants were nearly the only ones that paid the party dues."[34]

The FBI investigated rings of German saboteurs and spies starting in the late 1930s, and had primary responsibility for counterespionage. The first arrests of German agents were made in 1938 and continued throughout World War II.[35] In the Quirin affair, during World War II, German U-boats set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida and Long Island to cause acts of sabotage within the country. The two teams were apprehended after one of the men contacted the FBI and told them everything. He was also charged and convicted.[36] During the war and for many years afterward, the FBI maintained a fictionalized version of the story in which it had preempted and caught the saboteurs solely by its own investigations and had even infiltrated the German government. This story was useful during the war to discourage the Germans by making the FBI seem more invincible than it really was and perhaps afterward to similarly mislead the Soviets; but it also served Hoover in his efforts to maintain a superhero-style image for the FBI in American minds.

During this time period President Roosevelt, out of concern over Nazi agents in the United States, gave "qualified permission" to wiretap persons "suspected... [of] subversive activities". He went on to add, in 1941, that the United States Attorney General had to be informed of its use in each case.[37] The Attorney General Robert H. Jackson left it to Hoover to decide how and when to use wiretaps, as he found the "whole business" distasteful. Jackson's successor at the post of Attorney General, Francis Biddle, did turn down Hoover's requests on occasion.[38]

The FBI participated in the Venona Project, a pre–World War II joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet spies in the UK and the United States. They did not initially realize that espionage was being committed, but Soviet multiple use of one-time pad ciphers, which are normally unbreakable, created redundancies. This let some intercepts be decoded, which established the espionage. Hoover kept the intercepts—America's greatest counterintelligence secret—in a locked safe in his office, choosing not to inform President Truman, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath, or two Secretaries of State—Dean Acheson and General George Marshall—while they held office. He informed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

In 1946, Attorney General Tom C. Clark authorized Hoover to compile a list of potentially disloyal Americans who might be detained during a wartime national emergency. In 1950, at the outbreak of the Korean War, Hoover submitted to President Truman a plan to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Truman did not act on the plan.[39]

COINTELPRO and the 1950s

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by U.S. Supreme Court decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute people for their political opinions, most notably communists. Some of his aides reported that he purposely exaggerated the threat of communism to "ensure financial and public support for the FBI."[40] At this time he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO.[41]

This program remained in place until it was revealed to the public in 1971, after the theft of many internal documents from an office in Media, Pennsylvania, and COINTELPRO became the cause of some of the harshest criticism of Hoover and the FBI. COINTELPRO was first used to disrupt the Communist Party USA, where Hoover went after targets that ranged from suspected everyday spies to larger celebrity figures such as Charlie Chaplin, he saw as spreading Communist Party propaganda,[42] and later organizations such as the Black Panther Party, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and others. COINTELPRO's methods included infiltration, burglaries, illegal wiretaps, planting forged documents, and spreading false rumors about key members of target organizations.[43] Some authors have charged that COINTELPRO methods also included inciting violence and arranging murders.[44] In 1975, COINTELPRO's activities were investigated by the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, called the "Church Committee" after its chairman, Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho); the committee declared COINTELPRO's activities were illegal and contrary to the Constitution.[45] Hoover amassed significant power by collecting files containing large amounts of compromising and potentially embarrassing information on many powerful people, especially politicians. According to Laurence Silberman, appointed Deputy Attorney General in early 1974, FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley thought such files either did not exist or had been destroyed. After The Washington Post broke a story in January 1975, Kelley searched and found them in his outer office. The House Judiciary Committee then demanded that Silberman testify about them.

In 1956, several years before he targeted King, Hoover had a public showdown with T. R. M. Howard, a civil rights leader from Mound Bayou, Mississippi. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to thoroughly investigate the racially motivated murders of George W. Lee, Lamar Smith, and Emmett Till. Hoover wrote an open letter to the press singling out these statements as "irresponsible".

Response to Mafia and civil rights groups

While Hoover had fought bank-robbing gangsters in the 1930s, anti-communism was a bigger focus for him after World War II, as the Cold War developed. During the 1940s through mid-1950s, he seemed to ignore organized crime of the type that ran vice rackets such as drugs, prostitution, and extortion. He denied that any Mafia operated in the U.S. In the 1950s, evidence of Hoover's unwillingness to focus FBI resources on the Mafia became grist for the media and his many detractors. The Apalachin Meeting of late 1957 embarrassed the FBI by proving on newspaper front pages that a nationwide Mafia syndicate thrived unimpeded by the nation's "top cops". Hoover immediately changed tack, and during the next five years, the FBI investigated organized crime heavily. Its concentration on the topic fluctuated in subsequent decades, but it never again merely ignored this category of crime.

Hoover's moves against people who maintained contacts with subversive elements, some of whom were members of the civil rights movement, also led to accusations of trying to undermine their reputations. The treatment of Martin Luther King, Jr. and actress Jean Seberg are two examples. Jacqueline Kennedy recalled that Hoover told President John F. Kennedy that King tried to arrange a sex party while in the capital for the March on Washington and told Robert Kennedy that King made derogatory comments during the President's funeral.[46] However, King aide Andrew Young later claimed in a 2013 interview with the Academy of Achievement that the main source of tension between the SCLC and FBI was the government agency's lack of black agents and that both parties were willing to cooperate with each other by the time the Selma to Montgomery marches had taken place.[47]

Hoover personally directed the FBI investigation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In 1964, just days before Hoover testified in the earliest stages of the Warren Commission hearings, President Lyndon B. Johnson waived the then-mandatory U.S. Government Service Retirement Age of 70, allowing Hoover to remain the FBI Director "for an indefinite period of time."[48] The House Select Committee on Assassinations issued a report in 1979 critical of the performance by the FBI, the Warren Commission, and other agencies. The report also criticized what it characterized as the FBI's reluctance to thoroughly investigate the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.[49]

Late career

Presidents Harry S Truman and John F. Kennedy each considered dismissing Hoover as FBI Director, but ultimately concluded that the political cost of doing so would be too great.[50]

In 1964, Hoover's FBI investigated Jack Valenti, a special assistant and confidant of President Lyndon Johnson's. Despite Valenti's two-year marriage to Johnson's personal secretary, the investigation focused on rumors that he was having a gay relationship with a commercial photographer friend.[51]

When Richard Nixon took office in January 1969, Hoover had just turned 74. There was a growing sentiment in Washington, DC that the aging FBI chief needed to go, but Hoover's power and friends in Congress remained too strong for him to be forced into retirement.[52]

Pets

Hoover received his first dog from his parents when he was a child, after which he was never without one. He owned many throughout his lifetime and became an aficionado especially knowledgeable in fine breeding of pedigrees, particularly Cairn Terriers and Beagles. He gave away many dogs to notable people, such as Presidents Herbert Hoover (no relation) and Lyndon B. Johnson,[53] and buried seven canine pets, including a Cairn Terrier named Spee De Bozo, at Aspen Hill Memorial Park, in Silver Spring, Maryland.[54]

Death

Hoover remained director of the FBI until he died in his Washington home of a heart attack, on May 2, 1972.[55] His body lay in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, where Chief Justice Warren Burger eulogized him.[56] President Richard Nixon delivered another eulogy at the funeral service in the National Presbyterian Church, and called Hoover "one of the giants[, whose] long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to this country which he loved so well."[57] Hoover was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to the graves of his parents and a sister who died in infancy.[58]

Successor

Operational command of the Bureau passed to Associate Director Clyde Tolson. On May 3, Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray, a Justice Department official with no FBI experience, as Acting Director, with W. Mark Felt remaining as Associate Director.[59]

Legacy

Biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman notes: "For better or worse, he built the FBI into a modern, national organization stressing professionalism and scientific crime-fighting. For most of his life, Americans considered him a hero. He made the G-Man brand so popular that, at its height, it was harder to become an FBI agent than to be accepted into an Ivy League college."[5]

Hoover was a consultant to Warner Bros. for a theatrical film about the FBI, The FBI Story (1959), and in 1965 on Warner Bros.' long-running spin-off television series, The F.B.I. Hoover personally made sure Warner Bros. portrayed the FBI more favorably than other crime dramas of the times.

In 1979, there was a large increase in conflict in the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) under Senator Richard Schweiker, which had re-opened the investigation of the assassination of President Kennedy and reported that Hoover's FBI "failed to investigate adequately the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President". The HSCA further reported that Hoover's FBI "was deficient in its sharing of information with other agencies and departments".[60]

Because Hoover's actions came to be seen as abuses of power, FBI directors are now limited to one 10-year term,[61] subject to extension by the United States Senate.[62]

The FBI Headquarters in Washington, DC is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building, after Hoover. Because of the controversial nature of Hoover's legacy, there have been periodic proposals to rename it by legislation proposed by both Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate. For example, in 2001, Senator Harry Reid sponsored an amendment to strip Hoover's name from the building. "J. Edgar Hoover's name on the FBI building is a stain on the building", Reid said.[63] The Senate did not adopt the amendment.

Hoover's practice of violating civil liberties for the sake of national security has been questioned in reference to recent national surveillance programs. An example is a lecture titled "Civil Liberties and National Security: Did Hoover Get it Right?", given at The Institute of World Politics on April 21, 2015.[64]

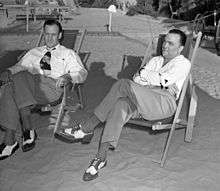

Sexuality

Since the 1940s, rumors had circulated that Hoover was homosexual.[65] The historians John Stuart Cox and Athan G. Theoharis speculated that Clyde Tolson, who became an associate director of the FBI and Hoover's primary heir, may have been his lover.[66] Hoover reportedly hunted down and threatened anyone who made insinuations about his sexuality.[67]

Some associates and scholars dismiss rumors about Hoover's sexuality, and his relationship with Tolson in particular, as unlikely,[68][69][70] while others have described them as probable or even "confirmed".[71][72] Still other scholars have reported the rumors without expressing an opinion.[73][74]

Hoover described Tolson as his alter ego: the men worked closely together during the day and, both single, frequently took meals, went to night clubs, and vacationed together.[66] This closeness between the two men is often cited as evidence that they were lovers, though some FBI employees who knew them, such as W. Mark Felt, say the relationship was "brotherly". The former FBI official Mike Mason suggested that some of Hoover's colleagues denied that he had a sexual relationship with Tolson in an effort to protect Hoover's image.[75]

Hoover bequeathed his estate to Tolson, who moved into Hoover's house after Hoover died. Tolson accepted the American flag that draped Hoover's casket. Tolson is buried a few yards away from Hoover in the Congressional Cemetery.[76]

Hoover's biographer Richard Hack does not believe the director was gay. Hack notes that Hoover was romantically linked to actress Dorothy Lamour in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and that after Hoover's death, Lamour did not deny rumors that she had had an affair with him in the years between her two marriages.[50] Hack further reported that, during the 1940s and 1950s, Hoover attended social events with Lela Rogers, the divorced mother of dancer and actress Ginger Rogers, so often that many of their mutual friends assumed the pair would eventually marry.[50]

In his biography Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover (1993), the journalist Anthony Summers quoted "society divorcee" Susan Rosenstiel as claiming to have seen Hoover engaging in cross-dressing in the 1950s, at homosexual parties.[77][78][79] Summers also said the Mafia had blackmail material on Hoover, which made Hoover reluctant to pursue organized crime aggressively. According to Summers, top organized crime figures Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello obtained photos of Hoover's alleged homosexual activity with Tolson and used them to ensure that the FBI did not target their illegal activities.[80] Additionally, Summers claimed that Hoover was friends with Billy Byars, Jr., an alleged child pornographer and producer of the film The Genesis Children.[81] Another Hoover biographer who heard the rumors of homosexuality and blackmail, however, said he was unable to corroborate them,[80] though it has been acknowledged that Lansky and other organized crime figures had frequently been allowed to visit the Del Charro Hotel in La Jolla, California, which was owned by Hoover's friend, and staunch Lyndon Johnson supporter,[82] Clint Murchison.[83] Hoover and Tolson would frequently visit the Del Charro Hotel as well.[83] Summers quoted a source named Charles Krebs as saying, "On three occasions that I knew about, maybe four, boys were driven down to La Jolla at Hoover's request."[81]

Although never corroborated, the allegation of cross-dressing has been widely repeated. In the words of author Thomas Doherty, "For American popular culture, the image of the zaftig FBI director as a Christine Jorgensen wanna-be was too delicious not to savor."[84] Biographer Kenneth Ackerman contends that Summers' accusations have been "widely debunked by historians."[85]

Skeptics of the cross-dressing story point to Susan Rosenstiel's poor credibility (she pleaded guilty to attempted perjury in a 1971 case and later served time in a New York City jail).[86][87] Recklessly indiscreet behavior by Hoover would have been totally out of character, whatever his sexuality. Most biographers consider the story of Mafia blackmail unlikely in light of the FBI's investigations of the Mafia.[88][89] Truman Capote, who helped spread salacious rumors about Hoover, once remarked that he was more interested in making Hoover angry than determining whether the rumors were true.[50]

The attorney Roy Cohn, who served as general counsel on the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations during Senator Joseph McCarthy's tenure as chairman and assisted Hoover during the 1950s investigations of Communists[90]—and who was generally known to be a closeted homosexual[90][91]—opined that Hoover was too frightened of his own sexuality to have anything approaching a normal sexual or romantic relationship.[50] During the Lavender Scare, Cohn and McCarthy further enhanced anti-Communist fervor by suggesting that Communists overseas had convinced several closeted homosexuals within the U.S. government to leak important government information in exchange for the assurance that their sexual identity would remain a secret.[90][92] A federal investigation that followed convinced President Dwight D. Eisenhower to sign an Executive Order on April 29, 1953, that barred homosexuals from obtaining jobs at the federal level.[93] In his 2004 study of the event, historian David K. Johnson attacked the speculations about Hoover's homosexuality as relying on "the kind of tactics Hoover and the security program he oversaw perfected—guilt by association, rumor, and unverified gossip." He views Rosenstiel as a liar who was paid for her story, whose "description of Hoover in drag engaging in sex with young blond boys in leather while desecrating the Bible is clearly a homophobic fantasy." He believes only those who have forgotten the virulence of the decades-long campaign against homosexuals in government can believe reports that Hoover appeared in compromising situations.[94]

Some people associated with Hoover have supported the rumors about his homosexual tendencies.[95] Actress and singer Ethel Merman, who was a friend of Hoover's since 1938, said in a 1978 interview, "Some of my best friends are homosexual. Everybody knew about J. Edgar Hoover, but he was the best chief the FBI ever had."[96] According to Anthony Summers, Hoover often frequented New York City's Stork Club. Luisa Stuart, a model who was 18 or 19 at the time, told Summers that she had seen Hoover holding hands with Tolson as they all rode in a limo uptown to the Cotton Club in 1936.[96]

The novelist William Styron told Summers that he once saw Hoover and Tolson in a California beach house, where the director was painting his friend's toenails.[96] Harry Hay, founder of the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay rights organizations, said Hoover and Tolson sat in boxes owned by and used exclusively by gay men at the Del Mar racetrack in California.[96] One medical expert told Summers that Hoover was of "strongly predominant homosexual orientation," while another medical expert categorized him as a "bisexual with failed heterosexuality."[95] Cox and Theoraris also alleged that "the strange likelihood is that Hoover never knew sexual desire at all."[70]

Honors

- 1938: Oklahoma Baptist University awarded Hoover an honorary doctorate during commencement exercises, at which he spoke.[97][98]

- 1939: the National Academy of Sciences awarded Hoover its Public Welfare Medal.[99]

- 1950: King George VI of the United Kingdom awarded Hoover an honorary knighthood in the Order of the British Empire.[100]

- 1955: President Dwight Eisenhower gave Hoover the National Security Medal.[101]

- 1966: President Lyndon B. Johnson bestowed the State Department's Distinguished Service Award on Hoover for his service as director of the FBI.

- 1973: The newly built FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building.

- 1974: Congress voted to honor Hoover's memory by publishing a memorial book, J. Edgar Hoover: Memorial Tributes in the Congress of the United States and Various Articles and Editorials Relating to His Life and Work

- 1974: In Schaumburg, Illinois, a grade school was named after J. Edgar Hoover. However, in 1994, after information about Hoover's criminal activity was released, the school's name was changed to commemorate Herbert Hoover, instead.[102]

Portrayals

J. Edgar Hoover has been portrayed by numerous actors in films and stage productions featuring him as FBI Director. Some notable portrayals (listed chronologically) include:

- Broderick Crawford and James Wainwright in the Larry Cohen film The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977).

- Dolph Sweet in the television miniseries King (1978).

- Ernest Borgnine in the television film Blood Feud (1983).

- Vincent Gardenia in the television miniseries Kennedy (1983).

- Jack Warden in the television film Hoover vs. The Kennedys (1987).

- Treat Williams in the television film J. Edgar Hoover (1987).

- Kevin Dunn in the film Chaplin (1992).

- Pat Hingle in the television film Citizen Cohn (1992).

- Richard Dysart in the television film Marilyn & Bobby: Her Final Affair (1993)

- Richard Dysart in the theatrical film Panther (1995).

- Bob Hoskins in the Oliver Stone drama Nixon (1995).

- Wayne Tippit in two episodes of Dark Skies (1996) and (1997).[103][104]

- David Fredericks in the episodes "Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man" (1996) and "Travelers" (1998) of The X-Files

- David Fredericks in the episode "Matryoshka" (1999) of Millennium

- Ernest Borgnine in the theatrical film Hoover (2000).

- Kelsey Grammer portrayed Hoover, with John Goodman as Tolson, in the Harry Shearer comic musical J. Edgar! on L.A. Theatre Works' The Play's the Thing (2001).

- Larry Drake in the Robert Dyke film Timequest (2002).

- Ryan Drummond voiced him in the Bethesda Softworks game Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth (2005).

- Billy Crudup in the Michael Mann film Public Enemies (2009).

- Enrico Colantoni in the television miniseries The Kennedys (2011).

- Leonardo DiCaprio in the Clint Eastwood biopic J. Edgar (2011).

- William Harrison-Wallace in the Dollar Baby 2012 screen adaptation of Stephen King's short story, "The Death of Jack Hamilton" (2001).[105]

- Rob Riggle in the "Atlanta" (2013) episode of Comedy Central's Drunk History.[106]

- Eric Ladin in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, season 4 (2013).[107]

- Michael McKean in Robert Schenkkan's play All the Way at the American Repertory Theater (2013).

- Sean McNall in the movie No God, No Master (2014).[108]

- Dylan Baker in Ava DuVernay's Martin Luther King biopic Selma (2014).

- Stephen Root in the HBO television film All the Way (2016).

Writings

J. Edgar Hoover was the nominal author of a number of books and articles. Although it is widely believed that all of these were ghostwritten by FBI employees,[109][110][111] Hoover received the credit and royalties.

- Hoover, J. Edgar (1938). Persons In Hiding. Gaunt Publishing. ISBN 1-56169-340-5.

- Hoover, J. Edgar (February 1947). "Red Fascism in the United States Today". American Magazine.

- Hoover, J. Edgar (1958). Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight It. Holt Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 1-4254-8258-9.[112]

- Hoover, J. Edgar (1962). A Study of Communism. Holt Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 0-03-031190-X.

See also

References

- ↑ ""J. Edgar Hoover", Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia". Microsoft Corporation. 2008. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009.

- ↑ ""Hoover, J. Edgar", The Columbia Encyclopedia" (Sixth ed.). Columbia University Press. 2007.

- ↑ Documented in Cox, John Stuart; Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-532-X. and elsewhere.

- ↑ "J. Edgar Hoover". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 Ackerman, Kenneth (November 9, 2011). "Five myths about J. Edgar Hoover". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Wines, Michael (June 5, 1991). "Tape Shows Nixon Feared Hoover". The New York Times.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (January 1, 2012). "The secret life of J Edgar Hoover". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Spannaus, Edward (August 2000). "The Mysterious Origins of J. Edgar Hoover". American Almanac.

- ↑ Cox, John Stuart; Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

- ↑ "The secret life of J Edgar Hoover". The Guardian. January 1, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Weiner, Tim (2012). "Anarchy". Enemies a history of the FBI (1 ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-64389-0.

- ↑ He was the closest to his mother in the family, who was the families moral guide and disciplinarian

- ↑ Burrough, Bryan (2009). Public Enemies: America's Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933-34. Penguin Books.

- ↑ "FBI — John Edgar Hoover". Fbi.gov. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- ↑ "J. Edgar Hoover's GW Years". GW Today. The George Washington University.

- ↑ "Prominent Alumni". The George Washington University. Archived from the original on 2010-06-11.

- ↑ "The Hoover Legacy, 40 Years After". FBI. 2012-06-28.

- 1 2 Weiner, Tim (2012). "Traitors". Enemies a history of the FBI (1 ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-64389-0.

- ↑ Murray, Robert K. (1955). Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 193. ISBN 0-8166-5833-1.

- ↑ Ruch was one of two people to name their own sons J. Edgar, and complained of the idea that radicals should "be allowed to speak and write as they like". See: Summers, 2011.

- ↑ Ellis, Mark (April 1994). "J. Edgar Hoover and the 'Red Summer' of 1919". Journal of American Studies. Cambridge University Press. 28 (1). JSTOR 27555783.

Hoover asked Anthony Caminetti, the Commissioner of the Bureau of Immigration, to consider deporting Garvey, forwarding an anonymous letter from New York about Garvey's alleged crookedness. Meanwhile, George Ruch placed Garvey at the top of a new central list of deportable radicals. On August 15, Hoover ordered a new investigation of Garvey's "aggressive activities" and the preparation of a deportation case. [...] eventually, in 1923, when Hoover was Assistant Director and Chief of the BI, he nailed Garvey for mail fraud. He was imprisoned in February 1925 and deported to Jamaica in November 1927.

- ↑ Kornweibel, Jr., Theodore (1998). "'The Most Colossal Conspiracy against the United States'". Seeing Red: Federal Campaigns Against Black Militancy, 1919–1925. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780253333377.

Convinced that the Crusader was 'financed by the Communist Party,' agents described Briggs as one of Rose Pastor Stokes's 'able assistants in this work.'

- ↑ Hoover, J. Edgar (August 23, 1919). "Memorandum for Mr. Creighton". Berkeley Digital Library: War Resistance, Anti-Militarism, and Deportation, 1917-1919. Washington, D.C.: Department of Justice. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman are, beyond doubt, two of the most dangerous anarchists in this country and if permitted to return to the community will result in undue harm.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (December 31, 2011). "The secret life of J Edgar Hoover". The Observer. London. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ Schott, Joseph L. (1975). No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-33630-1.

- ↑ Purvis, Alston; Tresinowski, Alex (2005). The Vendetta: FBI Hero Melvin Purvis's War Against Crime and J. Edgar Hoover's War Against Him. Public Affairs. pp. 183+. ISBN 1-58648-301-3.

- ↑ "Sheriff 26 Years – J. H. Flournoy Dies". Shreveport Journal. December 14, 1966. p. 1.

- ↑ Leroux, Charles (July 22, 1934). "John Dillinger's death". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Sifakis, Carl (1999). "The Mafia Encyclopedia". New York: Facts on File. p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Sifakis, p.127.

- ↑ "More Fingerprints Called Necessary... Hoover Urges Criminologists At Rochester To File Records In The Capital Bureau". The New York Times. July 23, 1931. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Washington Develops a World Clearing House For Identifying Criminals by Fingerprints". The New York Times. August 10, 1932. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

Through the medium of the fingerprint, the Department of Justice is developing an international clearing house for the identification of criminals.

- ↑ See, for example, Cox, John Stuart; Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

- ↑ Adam Bernstein (June 14, 2006). "Lawyer William G. Hundley, 80". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ↑ Breuer, William (1989). Hitler's Undercover War. New York: St. Matin's Press. ISBN 0-312-02620-X.

- ↑ Ardman, Harvey (February 1997). "German Saboteurs Invade America in 1942". World War II magazine. HistoryNet.com.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M. (2002). Robert Kennedy and His Times. p. 252.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M. (2002). Robert Kennedy and His Times. p. 253.

- ↑ Weiner, Tim (December 23, 2007). "Hoover Planned Mass Jailing in 1950.". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ↑ "From TIME's Archives: The Truth About J. Edgar Hoover". Time. December 22, 1975.

- ↑ Cox, John Stuart; Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. p. 312. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

- ↑ Sbardellati, John; Tony Shaw. Booting a Tramp: Charlie Chaplin, the FBI, and the Construction of the Subversive Image in Red Scare America.

- ↑ Kessler, Ronald (2002). The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. St. Martin's Paperbacks. pp. 107, 174, 184, 215. ISBN 0-312-98977-6.

- ↑ See for example James, Joy (2000). States of Confinement: Policing, Detention, and Prisons. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 335. ISBN 0-312-21777-3., Williams, Kristian (2004). Our Enemies In Blue: Police And Power In America. Soft Skull Press. p. 183. ISBN 1-887128-85-9. and Churchill, Ward; Wall, Jim Vander (2001). Agents of Repression: The FBI's Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. South End Press. pp. 53+. ISBN 0-89608-646-1.

- ↑ "Intelligence Activities And The Rights Of Americans". 1976. Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved October 25, 2006.

- ↑ Klein, Rick (2011). "Jacqueline Kennedy on Rev. Martin Luther King Jr". ABC News. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/printmember/you0int-1

- ↑ http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=106266

- ↑ "Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 1979. Retrieved October 25, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hack 2007

- ↑ Associated Press (February 20, 2009). "'Gay' Probe of LBJ Aide". NY Post. Washington, D.C.

- ↑ J. Edgar (2011)

- ↑ "Spee De Bozo". Find a Grave. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Grave of a Petey, Little Rascals Dog". Roadside America. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ Graham, Fred P. (May 3, 1972). "J. Edgar Hoover, 77, Dies; Will Lie in State in Capitol; J. Edgar Hoover Is Dead at 77; to Lie in State in Capitol". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ↑ Robertson, Nan (May 4, 1972). "Hoover Lies in State in Capitol; Eulogy Is Delivered by Chief Justice in Crowded Rotunda". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ Richard Nixon (May 4, 1972). "Richard Nixon: Eulogy Delivered at Funeral Services for J. Edgar Hoover". London: American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ↑ Robertson, Nan (May 5, 1972). "President Lauds Hoover; Nixon Terms Hoover a Giant of America". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Nixon Names Aide as Chief of FBI until Elections; Gray, an Assistant Attorney General, Chosen in a Move to Bar 'Partisan' Fight". The New York Times. May 4, 1972. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ "HCSA Conclusions, 1979". Archives.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ↑ Pub.L. 94–503, 90 Stat. 2427, : In note: Confirmation and Compensation of Director; Term of Service

- ↑ "Obama signs 2-year extension to Mueller's FBI tenure". CNN. July 26, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ↑ King, Colbert I. (May 5, 2001). "No thanks to Hoover". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Civil Liberties and National Security: Did Hoover Get it Right?". The Institute of World Politics. The Institute of World Politics. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Terry, Jennifer (1999). An American Obsession: Science, Medicine, and Homosexuality in Modern Society. University of Chicago Press. p. 350. ISBN 0-226-79366-4.

- 1 2 Cox, John Stuart; Theoharis, Athan G (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

- ↑ "J. Edgar Hoover: Gay marriage role model?". Salon. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- ↑ Felt, W. Mark; O'Connor, John D (2006). A G-man's Life: The FBI, Being 'Deep Throat,' And the Struggle for Honor in Washington. Public Affairs. p. 167. ISBN 1-58648-377-3.

- ↑ Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2003). Cloak and Dollar: A History of American Secret Intelligence. Yale University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-300-10159-7.

- 1 2 Cox, John Stuart; Theoharis, Athan G (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

The strange likelihood is that Hoover never knew sexual desire at all.

- ↑ Percy, William A.; Johansson, Warren (1994). Outing: Shattering the Conspiracy of Silence. Haworth Press. pp. 85+. ISBN 1-56024-419-4.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (1993). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J Edgar Hoover. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-88087-X.

- ↑ Theoharis, Athan G., ed. (1998). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Oryx Press. pp. 291, 301, 397. ISBN 0-89774-991-X.

- ↑ Doherty, Thomas (2003). Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 254, 255. ISBN 0-231-12952-1.

- ↑ Lengel, Allan (2011-01-09). "Movie depicting J Edgar Hoover gay affair rankles some in FBI". AOL News. Archived from the original on 2013-05-16.

- ↑ Boggs Roberts, Rebecca; Schmidt, Sandra K. (2012). Historic Congressional Cemetery. Arcadia Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 0-738-59224-2.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (1993). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J Edgar Hoover. Pocket Books. p. 254. ISBN 0-671-88087-X.

- ↑ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (February 15, 1993). "Books of The Times; Catalogue of Accusations Against J. Edgar Hoover". The New York Times. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ↑ Claire Bond Potter (July 2006). "Queer Hoover: Sex, Lies, and Political History". Journal of the History of Sexuality. Texas: University of Texas Press. 15 (3): 355–81. doi:10.1353/sex.2007.0021. ISSN 1535-3605.

What does the history of sex look like without evidence of sexual identities or proof that sex acts occurred? And how might an analysis of gossip, rumors, and perhaps even lies about sex help us to write political history?

- 1 2 Press, From Associated (1993-02-06). "J. Edgar Hoover Was Homosexual, Blackmailed by Mob, Book Says". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- 1 2 Summers, Anthony (2012). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover. Open Road Media. p. 244. ISBN 1-4532-4118-3.

- ↑ "Clinton Murchison Sr.". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- 1 2 "John Edgar Hoover". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ↑ Doherty, Thomas (2003). Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 255. ISBN 0-231-12952-1.

- ↑ Ackerman, Kenneth D. (November 14, 2011). "Five myths about J. Edgar Hoover". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (2012). Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover. Open Road Media. p. 295. ISBN 1-4532-4118-3.

- ↑ Holden, Henry M. (2008-04-15). FBI 100 Years: An Unofficial History. Zenith Imprint. p. 42. ISBN 0-7603-3244-4.

- ↑ Kessler, Ronald (2002). The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. St. Martin's Paperbacks. pp. 120+. ISBN 0-312-98977-6.

- ↑ Ronald Kessler. "Did J. Edgar Hoover Really Wear Dresses?". History News Network.

- ↑ Cohn, R. & Zion, S. (1988). The Autobiography of Roy Cohn. Lyle Stuart. pp. viii, 67, 142. ISBN 081840471X.

- ↑ Von Hoffman, N. (1988). Citizen Cohn. Doubleday. pp. 142–51. ISBN 0385236905.

- ↑ Eisenhower, Dwight D. "Security requirements for Government employment". Executive Order 10450. National Archives. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ↑ Johnson, David K. (2004). The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. University of Chicago Press. pp. 11–13.

- 1 2 "J. Edgar Hoover: Gay or Just a Man Who Has Sex With Men?". ABC News.

- 1 2 3 4 "J. Edgar Hoover: Gay or Just a Man Who Has Sex With Men?". ABC News. p. 2.

- ↑ "Honorary Doctorates". Oklahoma Baptist University. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ↑ "How the Angells changed OBU". December 15, 2004. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Public Welfare Award". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ The New York Times: "George VI Honors FBI Chief", December 11, 1947, retrieved February 17, 2011. This entitled him to use the letters KBE after his name, but not to the use of the title "Sir," since that title is restricted to citizen of countries belonging to the British Commonwealth.

- ↑ "Citation and Remarks at Presentation of the National Security Medal to J. Edgar Hoover".

- ↑ Winter, Christine (June 26, 1994). "Hoover School Gets A Name It Can Take Pride In". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "We Shall Overcome". Dark Skies. 1996.

- ↑ "The Warren Omission". Dark Skies. 1996.

- ↑ "'The Death of Jack Hamilton' official movie website". Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Atlanta". Drunk History. 2013.

- ↑ "Season 4". Boardwalk Empire.

- ↑ "No God, No Master". 2014.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (1999). Peace, War, and Politics: An Eyewitness Account. Forge Books. p. 174. ISBN 0-312-87497-9.

- ↑ Powers, Richard Gid (2004). Broken: the troubled past and uncertain future of the FBI. Free Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-684-83371-9.

- ↑ Theoharis, Athan G., ed. (1998). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Oryx Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-89774-991-X.

- ↑ Oakes, John B. (March 9, 1958). "Conspirators Against the American Way". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

Bibliography

- Kenneth D. Ackerman (2007). Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1775-0.

- William Beverly (2003). On the Lam; Narratives of Flight in J. Edgar Hoover's America. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-537-2.

- Carter, David (2003). Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked The Gay Revolution. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-34269-2.

- Douglas Charles (2007). J. Edgar Hoover and the Anti-interventionists: FBI Political Surveillance and the Rise of the Domestic Security State, 1939–1945. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-1061-1.

- Garrow, David J. (1981). The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr., From 'Solo' to Memphis. W.W.Norton. ISBN 0-393-01509-2.

- Gentry, Curt (1991). J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets. Plume. ISBN 0-452-26904-0.

- Hack, Richard (2007), Puppetmaster: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover, Phoenix Books, ISBN 1-59777-512-6

- Lowenthal, Max (1950). The Federal Bureau of Investigation. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8371-5755-2.

- Porter, Darwin (2012). J. Edgar Hoover and Clyde Tolson: Investigating the Sexual Secrets of America's Most Famous Men and Women. Blood Moon Productions. ISBN 1-936003-25-2.

- Richard Gid Powers (1986). Secrecy and Power: The Life of J. Edgar Hoover. Free Press. ISBN 0-02-925060-9.

- Joseph L. Schott (1975). No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-33630-1.

- Stove, Robert J. (2003). The Unsleeping Eye: Secret Police and Their Victims. Encounter Books. ISBN 1-893554-66-X.

- Summers, Anthony (2003). Official and Confidential:The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover. Putnam Publishing Group. ISBN 0-399-13800-5.

- Swearingen, M. Wesley. FBI Secrets An Agent's Expose.

- Theoharis, Athan (1993). From the Secret Files of J. Edgar Hoover. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-017-7.

- Frontline; The Secret File on J. Edgar Hoover (#11.4) 1993

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: J. Edgar Hoover |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to J. Edgar Hoover. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Assassination Records Review Board Staff (September 1998). Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board.

- FBI file on J. Edgar Hoover

- "J. Edgar Hoover". Find a Grave. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- Works by J. Edgar Hoover at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about J. Edgar Hoover at Internet Archive

- "J. Edgar Hoover Biography". Zpub.com.

Further reading

- Adams, Cecil (December 6, 2002). "Was J. Edgar Hoover a crossdresser?". The Straight Dope.

- Elias, Christopher (September 2, 2015). "A Lavender Reading of J. Edgar Hoover". Slate.

- Silberman, Laurence H. (July 20, 2005). "Hoover's Institution". Wall Street Journal.

- "The Truth about J. Edgar Hoover". TIME. December 22, 1975.

- Yardley, Jonathan (June 26, 2004). "'No Left Turns': The G-Man's Tour de Force". The Washington Post.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William J. Burns as Director of the Bureau of Investigation |

Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation Bureau of Investigation: 1924–1935 1924–1972 |

Succeeded by Pat Gray Acting |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Everett Dirksen |

Persons who have lain in state or honor in the United States Capitol rotunda May 3–4, 1972 |

Succeeded by Lyndon Johnson |