Shannon–Fano coding

In the field of data compression, Shannon–Fano coding, named after Claude Shannon and Robert Fano, is a technique for constructing a prefix code based on a set of symbols and their probabilities (estimated or measured). It is suboptimal in the sense that it does not achieve the lowest possible expected code word length like Huffman coding; however unlike Huffman coding, it does guarantee that all code word lengths are within one bit of their theoretical ideal .

The technique was proposed in Shannon's "A Mathematical Theory of Communication", his 1948 article introducing the field of information theory. The method was attributed to Fano, who later published it as a technical report.[1] Shannon–Fano coding should not be confused with Shannon coding, the coding method used to prove Shannon's noiseless coding theorem, or with Shannon–Fano–Elias coding (also known as Elias coding), the precursor to arithmetic coding.

Basic technique

In Shannon–Fano coding, the symbols are arranged in order from most probable to least probable, and then divided into two sets whose total probabilities are as close as possible to being equal. All symbols then have the first digits of their codes assigned; symbols in the first set receive "0" and symbols in the second set receive "1". As long as any sets with more than one member remain, the same process is repeated on those sets, to determine successive digits of their codes. When a set has been reduced to one symbol this means the symbol's code is complete and will not form the prefix of any other symbol's code.

The algorithm produces fairly efficient variable-length encodings; when the two smaller sets produced by a partitioning are in fact of equal probability, the one bit of information used to distinguish them is used most efficiently. Unfortunately, Shannon–Fano does not always produce optimal prefix codes; the set of probabilities {0.35, 0.17, 0.17, 0.16, 0.15} is an example of one that will be assigned non-optimal codes by Shannon–Fano coding.

For this reason, Shannon–Fano is almost never used; Huffman coding is almost as computationally simple and produces prefix codes that always achieve the lowest expected code word length, under the constraints that each symbol is represented by a code formed of an integral number of bits. This is a constraint that is often unneeded, since the codes will be packed end-to-end in long sequences. If we consider groups of codes at a time, symbol-by-symbol Huffman coding is only optimal if the probabilities of the symbols are independent and are some power of a half, i.e., . In most situations, arithmetic coding can produce greater overall compression than either Huffman or Shannon–Fano, since it can encode in fractional numbers of bits which more closely approximate the actual information content of the symbol. However, arithmetic coding has not superseded Huffman the way that Huffman supersedes Shannon–Fano, both because arithmetic coding is more computationally expensive and because it is covered by multiple patents.

Shannon–Fano coding is used in the IMPLODE compression method, which is part of the ZIP file format.[2]

Shannon–Fano Algorithm

A Shannon–Fano tree is built according to a specification designed to define an effective code table. The actual algorithm is simple:

- For a given list of symbols, develop a corresponding list of probabilities or frequency counts so that each symbol’s relative frequency of occurrence is known.

- Sort the lists of symbols according to frequency, with the most frequently occurring symbols at the left and the least common at the right.

- Divide the list into two parts, with the total frequency counts of the left part being as close to the total of the right as possible.

- The left part of the list is assigned the binary digit 0, and the right part is assigned the digit 1. This means that the codes for the symbols in the first part will all start with 0, and the codes in the second part will all start with 1.

- Recursively apply the steps 3 and 4 to each of the two halves, subdividing groups and adding bits to the codes until each symbol has become a corresponding code leaf on the tree.

Example

The example shows the construction of the Shannon code for a small alphabet. The five symbols which can be coded have the following frequency:

Symbol A B C D E Count 15 7 6 6 5 Probabilities 0.38461538 0.17948718 0.15384615 0.15384615 0.12820513

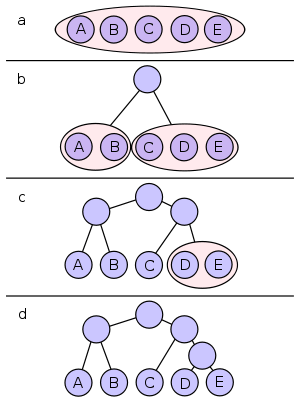

All symbols are sorted by frequency, from left to right (shown in Figure a). Putting the dividing line between symbols B and C results in a total of 22 in the left group and a total of 17 in the right group. This minimizes the difference in totals between the two groups.

With this division, A and B will each have a code that starts with a 0 bit, and the C, D, and E codes will all start with a 1, as shown in Figure b. Subsequently, the left half of the tree gets a new division between A and B, which puts A on a leaf with code 00 and B on a leaf with code 01.

After four division procedures, a tree of codes results. In the final tree, the three symbols with the highest frequencies have all been assigned 2-bit codes, and two symbols with lower counts have 3-bit codes as shown table below:

Symbol A B C D E Code 00 01 10 110 111

Results in 2 bits for A, B and C and per 3 bits for D and E an average bit number of

Huffman Algorithm

The Shannon–Fano algorithm doesn't always generate an optimal code. In 1952, David A. Huffman gave a different algorithm that always produces an optimal tree for any given symbol weights (probabilities). While the Shannon–Fano tree is created from the root to the leaves, the Huffman algorithm works in the opposite direction, from the leaves to the root.

- Create a leaf node for each symbol and add it to a priority queue, using its frequency of occurrence as the priority.

- While there is more than one node in the queue:

- Remove the two nodes of lowest probability or frequency from the queue

- Prepend 0 and 1 respectively to any code already assigned to these nodes

- Create a new internal node with these two nodes as children and with probability equal to the sum of the two nodes' probabilities.

- Add the new node to the queue.

- The remaining node is the root node and the tree is complete.

Example

Using the same frequencies as for the Shannon–Fano example above, viz:

Symbol A B C D E Count 15 7 6 6 5 Probabilities 0.38461538 0.17948718 0.15384615 0.15384615 0.12820513

In this case D & E have the lowest frequencies and so are allocated 0 and 1 respectively and grouped together with a combined probability of 0.28205128. The lowest pair now are B and C so they're allocated 0 and 1 and grouped together with a combined probability of 0.33333333. This leaves BC and DE now with the lowest probabilities so 0 and 1 are prepended to their codes and they are combined. This then leaves just A and BCDE, which have 0 and 1 prepended respectively and are then combined. This leaves us with a single node and our algorithm is complete.

The code lengths for the different characters this time are 1 bit for A and 3 bits for all other characters.

Symbol A B C D E Code 0 100 101 110 111

Results in 1 bit for A and per 3 bits for B, C, D and E an average bit number of

Notes

- ↑ Fano 1949

- ↑ "APPNOTE.TXT - .ZIP File Format Specification". PKWARE Inc. 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

The Imploding algorithm is actually a combination of two distinct algorithms. The first algorithm compresses repeated byte sequences using a sliding dictionary. The second algorithm is used to compress the encoding of the sliding dictionary output, using multiple Shannon–Fano trees.

References

- Shannon, C.E. (July 1948). "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. 27: 379–423.

- Fano, R.M. (1949). "The transmission of information". Technical Report No. 65. Cambridge (Mass.), USA: Research Laboratory of Electronics at MIT.