Siege of Eretria

| Siege of Eretria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

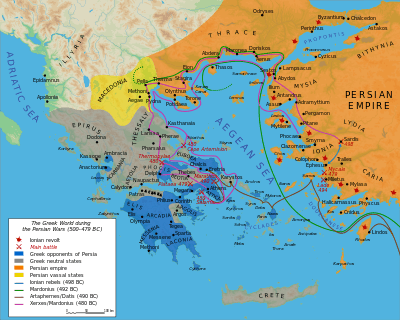

A map showing the invasion of 490 BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Eretria | Persian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown |

Datis, Artaphernes | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown |

Ancient sources: 100,000-300,000 men, 10,000 Persian Immortals, 600 ships c. 25,000 men (modern consensus) | ||||||

Location of the Siege of Eretria | |||||||

The Siege of Eretria took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. The city of Eretria, on Euboea, was besieged by a strong Persian force under the command of Datis and Artaphernes.

The first Persian invasion was a response to Greek involvement in the Ionian Revolt, when the Eretrians and Athenians had sent a force to support the cities of Ionia in their attempt to overthrow Persian rule. The Eretrian and Athenian force had succeeded in capturing and burning Sardis (the regional capital of Persia), but was then forced to retreat with heavy losses. In response to this raid, the Persian king Darius I swore to have revenge on Athens and Eretria.

Once the Ionian revolt was finally crushed by the Persian victory at the Battle of Lade, Darius began to plan to subjugate Greece. In 490 BC, he sent a naval task force under Datis and Artaphernes across the Aegean to subjugate the Cyclades, and then to make punitive attacks on Athens and Eretria. Reaching Euboea in mid-summer after a successful campaign in the Aegean, the Persians proceeded to put Eretria under siege. The siege lasted six days before a fifth column of Eretrian nobles betrayed the city to the Persians. The city was plundered, and the population enslaved on Darius's orders. The Eretrian prisoners were eventually taken to Persia and settled as colonists in Cissia.

After Eretria, the Persian force sailed for Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon. An Athenian army marched to meet them, and won a famous victory at the Battle of Marathon, thereby ending the first Persian invasion.

Sources

The main source for the Greco-Persian Wars is the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History',[1] was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek—Historia; English—(The) Histories) around 440–430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 450 BC).[2] Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it.[2] As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."[2]

Some subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, criticised Herodotus, starting with Thucydides.[3][4] Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and therefore evidently felt that Herodotus's history was accurate enough not to need re-writing or correcting.[4] Plutarch criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might actually have done a reasonable job of being even-handed.[5] A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read.[6] However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events.[7] The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism.[7] Nevertheless, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.[8]

The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus, writing in the 1st century BC in his Bibliotheca Historica, also provides an account of the Greco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's.[9] The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column, also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.[10]

Background

The first Persian invasion of Greece had its immediate roots in the Ionian Revolt, the earliest phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. However, it was also the result of the longer-term interaction between the Greeks and Persians. In 500 BC the Persian Empire was still relatively young and highly expansionistic, but prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples.[11][12][13] Moreover, the Persian king Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule.[11] Even before the Ionian Revolt, Darius had begun to expand the Empire into Europe, subjugating Thrace, and forcing Macedon to become a vassal of Persia.[14] Attempts at further expansion into the politically fractious world of Ancient Greece may have been inevitable.[12] However, the Ionian Revolt had directly threatened the integrity of the Persian empire, and the states of mainland Greece remained a potential menace to its future stability.[15] Darius thus resolved to subjugate and pacify Greece and the Aegean, and to punish those involved in the Ionian Revolt. [15][16]

The Ionian revolt had begun with an unsuccessful expedition against Naxos, a joint venture between the Persian satrap Artaphernes and the Miletus tyrant Aristagoras.[17] In the aftermath, Artaphernes decided to remove Aristagoras from power, but before he could do so, Aristagoras abdicated, and declared Miletus a democracy.[17] The other Ionian cities followed suit, ejecting their Persian-appointed tyrants, and declaring themselves democracies.[17][18] Artistagoras then appealed to the states of Mainland Greece for support, but only Athens and Eretria offered to send troops.[19]

The reasons that Eretria sent assistance to the Ionians are not completely clear. Possibly commercial reasons were a factor; Eretria was a mercantile city, whose trade was threatened by Persian dominance of the Aegean.[19] Herodotus suggests that the Eretrians supported the revolt in order to repay the support the Milesians had given Eretria in a past war against Chalcis.[20]

The Athenians and Eretrians sent a task force of 25 triremes to Asia Minor to aid the revolt.[21] Whilst there, the Greek army surprised and outmaneuvered Artaphernes, marching to Sardis and there burning the lower city.[22] However, this was as much as the Greeks achieved, and they were then pursued back to the coast by Persian horsemen, losing many men in the process. Despite the fact their actions were ultimately fruitless, the Eretrians and in particular the Athenians had earned Darius's lasting enmity, and he vowed to punish both cities.[23] The Persian naval victory at the Battle of Lade (494 BC) all but ended the Ionian Revolt, and by 493 BC, the last hold-outs were vanquished by the Persian fleet.[24] The revolt was used as an opportunity by Darius to extend the empire's border to the islands of the East Aegean[25] and the Propontis, which had not been part of the Persian dominions before.[26] The completion of the pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece, and to punish Athens and Eretria.[27]

In 492 BC, once the Ionian Revolt had finally been crushed, Darius dispatched an expedition to Greece under the command of his son-in-law, Mardonius. Mardonius re-conquered Thrace and compelled Alexander I of Macedon to make Macedon a client kingdom to Persia, before the wrecking of his fleet brought a premature end to the campaign.[28] However, in 490 BC, following up the successes of the previous campaign, Darius decided to send a maritime expedition led by Artaphernes, (son of the satrap to whom Hippias had fled) and Datis, a Median admiral. Mardonius had been injured in the prior campaign and had fallen out of favor. The expedition was intended to bring the Cyclades into the Persian empire, to punish Naxos (which had resisted a Persian assault in 499 BC) and then to head to Greece to force Eretria and Athens to submit to Darius or be destroyed.[29] After island hopping across the Aegean, including successfully attacking Naxos, the Persian task force arrived off Euboea in mid summer, ready to fulfil their second major objective - to punish Eretria.

Prelude

When the Eretrians had discovered that the Persian task force was heading to attack them, they had appealed to the Athenians to send reinforcements.[30] The Athenians agreed to this, and instructed the 4,000 Athenian colonists from the nearby Euboean city of Chalcis to aid the Eretrians.[30] These colonists had been planted on Chalcidian land after Athens had defeated Chalcis some 20 years previously.[31] However, when these Athenians arrived at Eretria, they were told by a leading citizen, Aeschines, of the divisions amongst the Eretrians, and he advised them to leave and save themselves.[30] The Athenians followed Aeschines' advice and sailed to Oropus, thus avoiding the fate of the Eretrians.[32]

The Eretrians failed to come to a clear plan of action; in Herodotus's words "it seems that all the plans of the Eretrians were unsound; they sent to the Athenians for aid, but their counsels were divided". There were three competing plans - one group wanted to surrender to the Persians, seeking to profit thereby, others wanted to flee to the hills above Eretria, whilst others wanted to fight.[30] However, when the Persians landed in their territory the Eretrians, some consensus was obviously reached not to leave the city, but to try to withstand a siege, if possible.[32]

Opposing forces

Eretrians

Herodotus does not estimate numbers for the Eretrians. Presumably, the majority of the citizen body would have been involved in the defence of the city, but the population of Eretria at the time cannot be clearly established.

Persians

According to Herodotus, the fleet sent by Darius consisted of 600 triremes.[33] Herodotus does not estimate the size of the Persian army, only saying that they were a "large infantry that was well packed".[34] Among ancient sources, the poet Simonides, another near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000; while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, of which only 100,000 fought in the battle, while the rest were loaded into the fleet that was rounding Cape Sounion;[35] Plutarch[36] and Pausanias[37] both independently give 300,000, as does the Suda dictionary.[38] Plato and Lysias assert 500,000;[39][40] and Justinus 600,000.[41]

Modern historians have proposed wide ranging numbers for the infantry, from 20,000–100,000 with a consensus of perhaps 25,000;[42][43][44][45] estimates for the cavalry are in the range of 1,000 [42]

Siege

The Eretrian strategy was to defend their walls, and undergo a siege.[32] Possibly this was the only plan that could be agreed on, or became the default option when no plan was agreed. At any rate, since the Persian army had only suffered two defeats in the last century, and since a Greek army had never successfully fought the Persians, this was probably a sensible strategy.[46] Since the Persians arrived by ship, it is probable they had little siege equipment, and indeed, they had already been foiled in the siege of Lindos earlier in the expedition.[47]

The Persians landed their army at three separate locations, disembarked, and made straight for Eretria.[32] The Persians then began besieging the city.[32] Rather than passively besieging the city, the Persians seem to have vigorously attacked the walls.[32] Herodotus reports that the fighting was fierce and both sides suffered heavy losses.[32] However, after six days of fighting, two eminent Eretrians, Euphorbus and Philagrus, opened the gates for the Persians.[32] Once inside the city, the Persians plundered the city, burning the temples and sanctuaries in revenge for the burning of Sardis.[32] Those citizens who were captured were enslaved, as Darius had ordered.[32]

Aftermath

After staying at Eretria for a few days, the Persians made their way down the coast towards Attica.[48] The Persians dropped the captured Eretrians off on the island of Aegilia, before landing at the bay of Marathon in Attica.[48][49] The Persians' next target was Athens. However, the Athenians had marched out from Athens to meet the Persians, and blocked the exits from the plains of Marathon.[50] After several days of stalemate, the Athenians finally resolved to attack the Persians, winning a famous victory at the ensuing Battle of Marathon.[51] After the battle, the remaining Persians fled to their ships, picked up the Eretrians from Aegilia,[51] and then sailed back to Asia Minor, thereby ending the campaign, and the first Persian invasion of Greece.[52]

When the Persian fleet arrived in Asia Minor, Datis and Artaphernes took the Eretrians before Darius in Susa.[53] The Eretrians were not harmed by Darius who decided to settle them in the town of Ardericca in Cissia.[53] They were still there, using their own language and customs, when Herodotus wrote his history,[53] and were encountered by Alexander the Great during his conquest of Persia a further century later.[54]

In the meanwhile, Darius began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.[13] Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I.[55] Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly restarted the preparations for the invasion of Greece.[56] The epic second Persian invasion of Greece finally began in 480 BC, and the Persians met with initial success at the battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium.[57] However, defeat at the Battle of Salamis would be the turning point in the campaign,[58] and the next year the expedition was ended by the decisive Greek victory at the Battle of Plataea.[59]

See also

References

- ↑ Cicero, On the Laws I, 5

- 1 2 3 Holland, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ↑ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, e.g. I, 22

- 1 2 Finley, p. 15.

- ↑ Holland, p. xxiv.

- ↑ David Pipes. "Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies". Archived from the original on January 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- 1 2 Holland, p. 377.

- ↑ Fehling, pp. 1–277.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XI, 28–34

- ↑ Note to Herodotus IX, 81

- 1 2 Holland, p47–55

- 1 2 Holland, p58–62

- 1 2 Holland, p203

- ↑ Roisman & Worthington 2011, p. 343.

- 1 2 Holland, 171–178

- ↑ Herodotus V, 105

- 1 2 3 Holland, p154–157

- ↑ Herodotus V, 97

- 1 2 Holland, p157–161

- ↑ Herodotus V, 98

- ↑ Herodotus V, 99

- ↑ Holland, p160

- ↑ Holland, p168

- ↑ Holland, p176

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 31

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 33

- ↑ Holland, p177–178

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 44

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 94

- 1 2 3 4 Herodotus VI, 100

- ↑ Herodotus V, 77

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Herodotus VI, 101

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 95

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 94

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades IV

- ↑ Plutarch, Moralia, 305 B

- ↑ Pausanias IV, 22

- ↑ Suda, entry Hippias

- ↑ Plato, Menexenus, 240 A

- ↑ Lysias, Funeral Oration, 21

- ↑ Justin II, 9

- 1 2 Lazenby, p46

- ↑ Holland, p390

- ↑ Lloyd, p164

- ↑ Green, p90

- ↑ Lazenby, pp23–29

- ↑ Lind. Chron. D 1–59 in Higbie (2003)

- 1 2 Herodotus VI,102

- ↑ Herodotus VI,107

- ↑ Herodotus VI,103

- 1 2 Herodotus VI,115

- ↑ Herodotus VI,116

- 1 2 3 Herodotus VI,119

- ↑ Fox, p543

- ↑ Holland, pp206–207

- ↑ Holland, pp208–211

- ↑ Lazenby, p151

- ↑ Lazenby, p197

- ↑ Holland, pp350–355

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Herodotus, The Histories Perseus online version

- Ctesias, Persica (excerpt in Photius's epitome)

- Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

- Cicero, On the Laws

- Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades

- Plutarch, Moralia

- Pausanias, Description of Greece

- Suda Dictionary (unknown author)

- Plato, Menexenus

- Justin, epitome of Trogus Pompeius's Philipic History

- Lysias, Funeral Oration

Modern sources

- Holland, Tom. Persian Fire. London: Abacus, 2005 (ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1)

- Lloyd, Alan. Marathon:The Crucial Battle That Created Western Democracy. Souvenir Press, 2004. (ISBN 0-285-63688-X)

- Green, Peter. The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970; revised ed., 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-20573-1); 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-20313-5).

- Lazenby, JF. The Defence of Greece 490–479 BC. Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1993 (ISBN 0-85668-591-7)

- Fox, Robin Lane. Alexander the Great. Penguin, 1973 (ISBN 0-14-008878-4)

- Fehling, D. Herodotus and His "Sources": Citation, Invention, and Narrative Art. Translated by J.G. Howie. Leeds: Francis Cairns, 1989.

- Finley, Moses (1972). "Introduction". Thucydides – History of the Peloponnesian War (translated by Rex Warner). Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044039-9.

- Higbie, C. The Lindian Chronicle and the Greek Creation of their Past. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-44-435163-7.

Coordinates: 38°23′34″N 23°47′39″E / 38.3928°N 23.7942°E