Mouth ulcer

| Oral ulcer | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | oral ulcer, mucosal ulcer |

| |

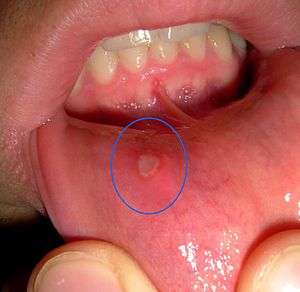

| A mouth ulcer (in this case associated with aphthous stomatitis) on the labial mucosa (lining of the lower lip). | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Oral medicine |

| ICD-10 | K12 |

| ICD-9-CM | 528.9 |

| DiseasesDB | 22751 |

| MedlinePlus | 001448 |

| MeSH | D019226 |

A mouth ulcer is an ulcer that occurs on the mucous membrane of the oral cavity.[1] Mouth ulcers are very common, occurring in association with many diseases and by many different mechanisms, but usually there is no serious underlying cause.

The two most common causes of oral ulceration are local trauma (e.g. rubbing from a sharp edge on a broken filling) and aphthous stomatitis ("canker sores"), a condition characterized by recurrent formation of oral ulcers for largely unknown reasons. Mouth ulcers often cause pain and discomfort, and may alter the person's choice of food while healing occurs (e.g. avoiding acidic or spicy foods and beverages).

They may form individually or multiple ulcers may appear at the same time (a "crop" of ulcers). Once formed, the ulcer may be maintained by inflammation and/or secondary infection. Rarely, a mouth ulcer that does not heal may be a sign of oral cancer.

Definition

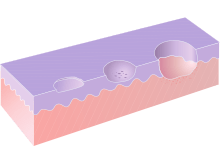

An ulcer (/ˈʌlsər/; from Latin ulcus, "ulcer, sore")[2] is a break in the skin or mucous membrane with loss of surface tissue and the disintegration and necrosis of epithelial tissue.[3] A mucosal ulcer is an ulcer which specifically occurs on a mucous membrane. An ulcer is a tissue defect which has penetrated the epithelial-connective tissue border, with its base at a deep level in the submucosa, or even within muscle or periosteum.[4] An ulcer is a deeper breach of the epithelium than an erosion or an excoriation, and involves damage to both epithelium and lamina propria.[5]

An erosion is a superficial breach of the epithelium, with little damage to the underlying lamina propria.[5] A mucosal erosion is an erosion which specifically occurs on a mucous membrane. Only the superficial epithelial cells of the epidermis or of the mucosa are lost, and the lesion can reach the depth of the basement membrane.[4] Erosions heal without scar formation.[4]

Excoriation is a term sometimes used to describe a breach of the epithelium which is deeper than an erosion but shallower than an ulcer. This type of lesion is tangential to the rete pegs and shows punctiform (small pinhead spots) bleeding, caused by exposed capillary loops.[4]

Differential diagnosis

Aphthous stomatitis and local trauma are very common causes of oral ulceration; the many other possible causes are all rare in comparison.

Traumatic ulceration

Most mouth ulcers that are not associated with recurrent aphthous stomatitis are caused by local trauma. The mucous membrane lining of the mouth is thinner than the skin, and easily damaged by mechanical, thermal (heat/cold), chemical, or electrical means, or by irradiation.

Mechanical

Common causes of oral ulceration include rubbing on sharp edges of teeth, fillings, crowns, false teeth (dentures), or braces (orthodontic appliances). Accidental biting caused by a lack of awareness of painful stimuli in the mouth (e.g., following local anesthetic use during dental treatment) may cause ulceration which the person becomes aware of as the anesthetic wears off and the full sensation returns.

Eating rough foods (e.g., potato chips) can damage the lining of the mouth. Some people cause damage inside their mouths themselves, either through an absentminded habit or as a type of deliberate self-harm (factitious ulceration). Examples include biting the cheek, tongue, or lips, or rubbing a fingernail, pen, or toothpick inside the mouth. Tearing (and subsequent ulceration) of the upper labial frenum may be a sign of child abuse (non-accidental injury).[5] Iatrogenic ulceration can also occur during dental treatment, when incidental abrasions to the soft tissues of the mouth are common. Some dentists apply a protective layer of petroleum jelly to the lips before carrying out dental work to minimize the number of incidental injuries.

The lingual frenum is also vulnerable to ulceration by repeated friction during oral sexual activity ("cunnilingus tongue").[6]

Thermal and electrical burn

Thermal burns usually result from placing hot food or beverages in the mouth. This may occur in those who eat or drink before a local anesthetic has worn off. The normal painful sensation is absent and a burn may occur. Microwave ovens sometimes produce food which is cold externally and very hot internally, and this has led to a rise in the frequency of intra-oral thermal burns. Thermal food burns are usually on the palate or posterior buccal mucosa, and appear as zones of erythema and ulceration with necrotic epithelium peripherally. Electrical burns more commonly affect the oral commissure (corner of the mouth). The lesions are usually initially painless, charred and yellow with little bleeding. Swelling then develops and by the fourth day following the burn the area becomes necrotic and the epithelium sloughs off.[6]

Electrical burns in the mouth are usually caused by chewing on live electrical wiring (an act that is relatively common among young children). Saliva acts as a conducting medium and an electrical arc flows between the electrical source and the tissues, causing extreme heat and possible tissue destruction.[6][7]

Chemical injury

Caustic chemicals may cause ulceration of the oral mucosa if they are of strong-enough concentration and in contact for a sufficient length of time. The holding of medication in the mouth instead of swallowing it occurs mostly in children, those under psychiatric care, or simply because of a lack of understanding. Holding an aspirin tablet next to a painful tooth in an attempt to relieve pulpitis (toothache) is common, and leads to epithelial necrosis. Chewable aspirin tablets should be swallowed, with the residue quickly cleared from the mouth.

Other caustic medications include eugenol and chlorpromazine. Hydrogen peroxide, used to treat gum disease, is also capable of causing epithelial necrosis at concentrations of 1–3%. Silver nitrate, sometimes used for pain relief from aphthous ulceration, acts as a chemical cauterant and destroys nerve endings, but the mucosal damage is increased. Phenol is used during dental treatment as a cavity sterilizing agent and cauterizing material, and it is also present in some over-the-counter agents intended to treat aphthous ulcerations. Mucosal necrosis has been reported to occur with concentrations of 0.5%. Other materials used in endodontics are also caustic, which is part of the reason why use of a rubber dam is now recommended.[6]

Irradiation

As a result of radiotherapy to the mouth, radiation-induced stomatitis may develop, which can be associated with mucosal erosions and ulceration. If the salivary glands are irradiated, there may also be xerostomia (dry mouth), making the oral mucosa more vulnerable to frictional damage as the lubricating function of saliva is lost, and mucosal atrophy (thinning), which makes a breach of the epithelium more likely. Radiation to the bones of the jaws causes damage to osteocytes and impairs the blood supply. The affected hard tissues become hypovascular (reduced number of blood vessels), hypocellular (reduced number of cells), and hypoxic (low levels of oxygen). Osteoradionecrosis is the term for when such an area of irradiated bone does not heal from this damage. This usually occurs in the mandible, and causes chronic pain and surface ulceration, sometimes resulting in non-healing bone being exposed through a soft tissue defect. Prevention of osteradionecrosis is part of the reason why all teeth of questionable prognosis are removed before the start of a course of radiotherapy.[6]

Aphthous stomatitis

Aphthous stomatitis (also termed recurrent aphthous stomatits, RAS, and commonly called "canker sores") is a very common cause of oral ulceration. 10–25% of the general population suffer from this non-contagious condition. The appearance of aphthous stomatitis varies as there are 3 types, namely minor aphthous ulceration, major aphthous ulceration and herpetiform ulceration. Minor aphthous ulceration is the most common type, presenting with 1–6 small (2-4mm diameter), round/oval ulcers with a yellow-grey color and an erythematous (red) "halo". These ulcers heal with no permanent scarring in about 7–10 days. Ulcers recur at intervals of about 1–4 months. Major aphthous ulceration is less common than the minor type, but produces more severe lesions and symptoms. Major aphthous ulceration presents with larger (>1 cm diameter) ulcers that take much longer to heal (10–40 days) and may leave scarring. The minor and major subtypes of aphthous stomatitis usually produce lesions on the non-keratinized oral mucosa (i.e. the inside of the cheeks, lips, underneath the tongue and the floor of mouth), but less commonly major aphthous ulcers may occur in other parts of the mouth on keratinized mucosal surfaces. The least common type is herpetiform ulceration, so named because the condition resembles primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Herpetiform ulcers begin as small blisters (vesicles) which break down into 2-3mm sized ulcers. Herpetiform ulcers appear in "crops" sometimes hundreds in number, which can coalesce to form larger areas of ulceration. This subtype may cause extreme pain, heals with scarring and may recur frequently.

The exact cause of aphthous stomatitis is unknown, but there may be a genetic predisposition in some people. Other possible causes include hematinic deficiency (folate, vitamin B, iron), stopping smoking, stress, menstruation, trauma, food allergies or hypersensitivity to sodium lauryl sulphate (found in many brands of toothpaste). Aphthous stomatitis has no clinically detectable signs or symptoms outside the mouth, but the recurrent ulceration can cause much discomfort to sufferers. Treatment is aimed at reducing the pain and swelling and speeding healing, and may involve systemic or topical steroids, analgesics (pain killers), antiseptics, anti-inflammatories or barrier pastes to protect the raw area(s).[5]

Infection

| Agent | Example(s) |

| Viral | chickenpox, hand, foot and mouth disease, herpangina, herpetic stomatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, infectious mononucleosis |

| Bacterial | acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, syphilis, tuberculosis |

| Fungal | blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis |

| Parasitic | leishmaniasis |

Many infections can cause oral ulceration (see table). The most common are herpes simplex virus (herpes labialis, primary herpetic gingivostomatitis), varicella zoster (chicken pox, shingles), and coxsackie A virus (hand, foot and mouth disease). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) creates immunodeficiencies which allow opportunistic infections or neoplasms to proliferate. Bacterial processes leading to ulceration can be caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (tuberculosis) and Treponema pallidum (syphilis).

Opportunistic activity by combinations of otherwise normal bacterial flora, such as aerobic streptococi, Neisseria, Actinomyces, spirochetes, and Bacteroides species can prolong the ulcerative process. Fungal causes include Coccidioides immitis (valley fever), Cryptococcus neoformans (cryptococcosis), and Blastomyces dermatitidis ("North American Blastomycosis").[8] Entamoeba histolytica, a parasitic protozoan, is sometimes known to cause mouth ulcers through formation of cysts.

Drug-induced

Many drugs can cause mouth ulcers as a side effect. Common examples are alendronate[9] (a bisphosphonate, commonly prescribed for osteoporosis), cytotoxic drugs (e.g. methotrexate, i.e. chemotherapy), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nicorandil[10] (may be prescribed for angina) and propylthiouracil (e.g. used for hyperthyroidism). Some recreational drugs can cause ulceration, e.g. cocaine.[11]

Malignancy

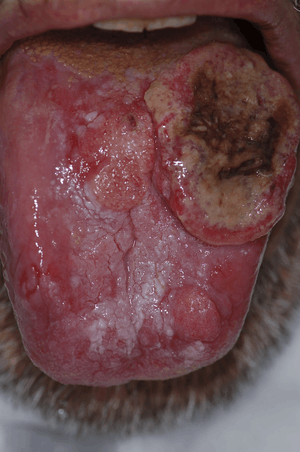

Rarely, a persistent, non-healing mouth ulcer may be a cancerous lesion. Malignancies in the mouth are usually carcinomas, but lymphomas, sarcomas and others may also be possible. Either the tumor arises in the mouth, or it may grow to involve the mouth, e.g. from the maxillary sinus, salivary glands, nasal cavity or peri-oral skin. The most common type of oral cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. The main causes are long-term smoking and alcohol consumption (particularly together) and betel use.

Common sites of oral cancer are the lower lip, the floor of the mouth, and the sides and underside of the tongue, but it is possible to have a tumor anywhere in the mouth. Appearances vary greatly, but a typical malignant ulcer would be a persistent, expanding lesion which is totally red (erythroplasia) or speckled red and white (erythroleukoplakia). Malignant lesions also typically feel indurated (hardened) and attached to adjacent structures, with "rolled" margins or a punched out appearance and bleeds easily on gentle manipulation.[12]

Vesiculobullous diseases

Due to various factors (saliva, relative thinness of oromucosa, trauma from teeth, chewing, etc.), vesicles and bullae which form on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity tend to be fragile and quickly break down to leave ulcers.

Some of the viral infections mentioned above are also classified as vesiculobullous diseases. Other example vesiculobullous diseases include pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid, bullous pemphigoid, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and epidermolysis bullosa.[13]:1,22

Allergy

Rarely, allergic reactions of the mouth and lips may manifest as erosions; however, such reactions usually do not produce frank ulceration. An example of one common allergen is Balsam of Peru. If individuals allergic to this substance have oral exposure they may experience stomatitis and cheilitis (inflammation, rash, or painful erosion of the lips, oropharyngeal mucosa, or angles of their mouth).[14][15][16][17] Balsam of Peru is used in foods and drinks for flavoring, in perfumes and toiletries for fragrance, and in medicine and pharmaceutical items for healing properties.[14][15][16]

Other causes

A wide range of other diseases may cause mouth ulcers. Hematological causes include anemia, hematinic deficiencies, neutropenia, hypereosinophilic syndrome, leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, other white cell dyscrasias, and gammopathies. Gastrointestinal causes include celiac disease, Crohn's disease (orofacial granulomatosis), and ulcerative colitis. Dermatological causes include chronic ulcerative stomatitis, erythema multiforme (Stevens-Johnson syndrome), angina bullosa haemorrhagica and lichen planus. Other examples of systemic disease capable of causing mouth ulcers include lupus erythematosus, Sweet syndrome, reactive arthritis, Behçet syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, periarteritis nodosa, giant cell arteritis, diabetes, glucagonoma, sarcoidosis and periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis.[5]

The conditions eosinophilic ulcer and necrotizing sialometaplasia may present as oral ulceration.

Macroglossia, an abnormally large tongue, can be associated with ulceration if the tongue protrudes constantly from the mouth.[6] Caliber persistent artery describes a common vascular anomaly where a main arterial branch extends into superficial submucosal tissues without a reduction of diameter. This commonly occurs in elderly people on the lip and may be associated with ulceration.[6]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenesis is dependent upon the cause. Ulcers and erosions can be the result of a spectrum of conditions including those causing auto-immune epithelial damage, damage because of an immune defect (e.g. HIV, leukemia, infections e.g. herpes viruses) or nutritional disorders (e.g. vitamin deficiencies). Simple mechanisms which predispose the mouth to trauma and ulceration are xerostomia (dry mouth – as saliva usually lubricates the mucous membrane and controls bacterial levels) and epithelial atrophy (thinning, e.g. after radiotherapy), making the lining more fragile and easily breached.[18]:7 Stomatitis is a general term meaning inflammation within the mouth, and often may be associated with ulceration.[19]

Pathologically, the mouth represents a transition between the gastrointestinal tract and the skin, meaning that many gastrointestinal and cutaneous conditions can involve the mouth. Some conditions usually associated with the whole gastrointestinal tract may present only in the mouth, e.g. orofacial granulomatosis/oral Crohn's disease.[20]

Similarly, cutaneous (skin) conditions can also involve the mouth and sometimes only the mouth, sparing the skin. The different environmental conditions (saliva, thinner mucosa, trauma from teeth and food), mean that some cutaneous disorders which produce characteristic lesions on the skin produce only non specific lesions in the mouth.[21] The vesicles and bullae of blistering mucocutaneous disorders progress quickly to ulceration in the mouth, because of moisture and trauma from food and teeth. The high bacterial load in the mouth means that ulcers may become secondarily infected. Cytotoxic drugs administered during chemotherapy target cells with fast turnovers such as malignant cells. However, the epithelia of the mouth also has a high turnover rate and makes oral ulceration (mucositis) a common side effect of chemotherapy.

Erosions, which involve the epithelial layer, are red in appearance since the underlying lamina propria shows through. When the full thickness of the epithelium is penetrated (ulceration), the lesion becomes covered with a fibrinous exudate and takes on a yellow-grey color. Because an ulcer is a breach of the normal lining, when seen in cross section, the lesion is a crater. A "halo" may be present, which is a reddening of the surrounding mucosa and is caused by inflammation. There may also be edema (swelling) around the ulcer. Chronic trauma may produce an ulcer with a keratotic (white, thickened mucosa) margin.[5] Malignant lesions may ulcerate either because the tumor infiltrates the mucosa from adjacent tissues, or because the lesion originates within the mucosa itself, and the disorganized growth leads to a break in the normal architecture of the lining tissues. Repeat episodes of mouth ulcers can be indicative of an immunodeficiency, signaling low levels of immunoglobulin in the oral mucous membranes. Chemotherapy, HIV, and mononucleosis are all causes of immunodeficiency/immunosuppression with which oral ulcers may become a common manifestation. Autoimmunity is also a cause of oral ulceration. Mucous membrane pemphigoid, an autoimmune reaction to the epithelial basement membrane, causes desquamation/ulceration of the oral mucosa. Numerous aphthous ulcers could be indicative of an inflammatory autoimmune disease called Behçet's disease. This can later involve skin lesions and uveitis in the eyes. Vitamin C deficiency may lead to scurvy which impairs wound healing, which can contribute to ulcer formation.[8] For a detailed discussion of the pathophysiology of aphthous stomatitis, see Aphthous stomatitis#Causes.

Diagnostic approach

Diagnosis of mouth ulcers usually consists of a medical history followed by an oral examination as well as examination of any other involved area. The following details may be pertinent: The duration that the lesion has been present, the location, the number of ulcers, the size, the color and whether it is hard to touch, bleeds or has a rolled edge. As a general rule, a mouth ulcer that does not heal within 2 or 3 weeks should be examined by a health care professional who is able to rule out oral cancer (e.g. a dentist, oral physician, oral surgeon, or maxillofacial surgeon).[1][22] If there have been previous ulcers which have healed, then this again makes cancer unlikely.

An ulcer that keeps forming on the same site and then healing may be caused by a nearby sharp surface, and ulcers that heal and then recur at different sites are likely to be RAS. Malignant ulcers are likely to be single in number, and conversely, multiple ulcers are very unlikely to be oral cancer. The size of the ulcers may be helpful in distinguishing the types of RAS, as can the location (minor RAS mainly occurs on non-keratinizing mucosa, major RAS occurs anywhere in the mouth or oropharynx). Induration, contact bleeding and rolled margins are features of a malignant ulcer. There may be nearby causative factor, e.g. a broken tooth with a sharp edge that is traumatizing the tissues. Otherwise, the person may be asked about problems elsewhere, e.g. ulceration of the genital mucous membranes,[23] eye lesions or digestive problems, swollen glands in neck (lymphadenopathy) or a general unwell feeling.

The diagnosis comes mostly from the history and examination, but the following special investigations may be involved: blood tests (vitamin deficiency, anemia, leukemia, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV infection, diabetes) microbiological swabs (infection), or urinalysis (diabetes). A biopsy (minor procedure to cut out a small sample of the ulcer to look at under a microscope) with or without immunofluorescence may be required, to rule out cancer, but also if a systemic disease is suspected.[5] Ulcers caused by local trauma are painful to touch and sore. They usually have an irregular border with erythematous margins and the base is yellow. As healing progresses, a keratotic (thickened, white mucosa) halo may occur.[18]:52

Treatment

Treatment is cause-related, but also symptomatic if the underlying cause is unknown or not correctable. It is also important to note that most ulcers will heal completely without any intervention. Treatment can range from simply smoothing or removing a local cause of trauma, to addressing underlying factors such as dry mouth or substituting a problem medication. Maintaining good oral hygiene and use of an antiseptic mouthwash or spray (e.g. chlorhexidine) can prevent secondary infection and therefore hasten healing. A topical analgesic (e.g. benzydamine mouthwash) may reduce pain. Topical (gels, creams or inhalers) or systemic steroids may be used to reduce inflammation. An antifungal drug may be used to prevent oral candidiasis developing in those who use prolonged steroids.[5] People with mouth ulcers may prefer to avoid hot or spicy foods, which can increase the pain.[1] Self-inflicted ulceration can be difficult to manage, and psychiatric input may be required in some people.[18]:53 In the last decade treatment of mouth ulcers with cold lasers has become increasingly common among dentists. The laser essentially cauterizes the wound which sterilises it reducing pain and inflammation and speeding healing. Such treatment may be a particular relief to patients with recurring, slow healing or painful ulcers.

Epidemiology

Oral ulceration is a common reason for people to seek medical or dental advice.[18]:52 A breach of the oral mucosa probably affects most people at various times during life. For a discussion of the epidemiology of aphthous stomatitis, see Aphthous stomatitis#Epidemiology.

References

- 1 2 3 Vorvick LJ, Zieve D. "Mouth ulcers on MedlinePlus". A.D.A.M., Inc. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ "Ulcer Origin". dictionary.com. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ulcer on Merriam-Webster medical dictionary". Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Loevy, Manfred Strassburg, Gerdt Knolle ; translated by Hannelore Taschini (1993). Diseases of the Oral Mucosa : A Colour Atlas. (2nd ed.). Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co., U.S. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-86715-210-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Scully, Crispian (2008). "Chapter 14: Soreness and ulcers". Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 131–139. ISBN 978-0-443-06818-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BW Neville; DD Damm; CM Allen; JE Bouquot (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2. ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 253–284. ISBN 0-7216-9003-3.

- ↑ Toon MH, Maybauer DM, Arceneaux LL, Fraser JF, Meyer W, Runge A, Maybauer MO (2011). "Children with burn injuries-assessment of trauma, neglect, violence and abuse". Journal of Injury and Violence Research. 3 (2): 98–110. doi:10.5249/jivr.v3i2.91. PMC 3134932

. PMID 21498973.

. PMID 21498973. - 1 2 Sapp, J. Phillip; Lewis Roy Eversole; George W. Wysocki (2004). Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Mosby. ISBN 0-323-01723-1.

- ↑ Kharazmi M, Sjöqvist K, Warfvinge G (April 2012). "Oral ulcers, a little known adverse effect of alendronate: review of the literature". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 70 (4): 830–6. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.046. PMID 21816532.

- ↑ Healy CM, Smyth Y, Flint SR (July 2004). "Persistent nicorandil induced oral ulceration". Heart (British Cardiac Society). 90 (7): e38. doi:10.1136/hrt.2003.031831. PMC 1768343

. PMID 15201264.

. PMID 15201264. - ↑ Fazzi M, Vescovi P, Savi A, Manfredi M, Peracchia M (October 1999). "[The effects of drugs on the oral cavity]". Minerva stomatologica. 48 (10): 485–92. PMID 10726452.

- ↑ Tucker, editors, James R. Hupp, Edward Ellis, Myron R. (2008). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery (5th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-323-04903-0.

- ↑ Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RK (2011). Oral pathology : clinical pathologic correlations (6th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1455702626.

- 1 2 "Balsam of Peru contact allergy". Dermnetnz.org. December 28, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- 1 2 Gottfried Schmalz; Dorthe Arenholt Bindslev (2008). Biocompatibility of Dental Materials. Springer. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- 1 2 Thomas P. Habif (2009). Clinical Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Edward T. Bope; Rick D. Kellerman (2013). Conn's Current Therapy 2014: Expert Consult. Elsevier Health Sciences. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Tyldesley, Anne Field, Lesley Longman in collaboration with William R. (2003). Tyldesley's Oral medicine (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 7–8, 25, 35, 41, 43–44, 51–56. ISBN 0-19-263147-0.

- ↑ RA Cawson; EW Odell; S Porter (2002). Cawson's essentials of oral pathology and oral medicine. (7. ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 178–191. ISBN 0-443-07106-3.

- ↑ Zbar AP, Ben-Horin S, Beer-Gabel M, Eliakim R (March 2012). "Oral Crohn's disease: is it a separable disease from orofacial granulomatosis? A review". Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 6 (2): 135–42. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.07.001. PMID 22325167.

- ↑ Glick, Martin S. Greenberg, Michael (2003). Burket's oral medicine diagnosis & treatment (10th ed.). Hamilton, Ont.: BC Decker. pp. 50–79. ISBN 1-55009-186-7.

- ↑ Scully C, Shotts R (15 July 2000). "ABC of oral health. Mouth ulcers and other causes of orofacial soreness and pain". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 321 (7254): 162–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7254.162. PMC 1118165

. PMID 10894697.

. PMID 10894697. - ↑ Keogan MT (April 2009). "Clinical Immunology Review Series: an approach to the patient with recurrent orogenital ulceration, including Behçet's syndrome". Clinical and experimental immunology. 156 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03857.x. PMC 2673735

. PMID 19210521.

. PMID 19210521.

External links

-

Learning materials related to Oral ulceration at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Oral ulceration at Wikiversity - Mouth ulcer at DMOZ