Earle Page

| The Right Honourable Sir Earle Christmas Page GCMG, CH | |

|---|---|

| |

| 11th Prime Minister of Australia | |

|

In office 7 April – 26 April 1939 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Governor-General | Lord Gowrie |

| Preceded by | Joseph Lyons |

| Succeeded by | Robert Menzies |

| Minister for Health | |

|

In office 19 December 1949 – 11 January 1956 | |

| Prime Minister | Robert Menzies |

| Preceded by | Nick McKenna |

| Succeeded by | Donald Cameron |

|

In office 29 November 1937 – 7 November 1938 | |

| Prime Minister | Joseph Lyons |

| Preceded by | Billy Hughes |

| Succeeded by | Harry Foll |

| Minister for Commerce | |

|

In office 28 October 1940 – 7 October 1941 | |

| Prime Minister | Robert Menzies |

| Preceded by | Archie Cameron |

| Succeeded by | William Scully |

|

In office 9 November 1932 – 26 April 1939 | |

| Prime Minister |

Joseph Lyons Earle Page |

| Preceded by | Frederick Stewart |

| Succeeded by | George McLeay |

| Treasurer of Australia | |

|

In office 9 February 1923 – 21 October 1929 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Bruce |

| Preceded by | Stanley Bruce |

| Succeeded by | Ted Theodore |

| Leader of the Country Party | |

|

In office 5 April 1921 – 13 September 1939 | |

| Deputy |

Edmund Jowett Henry Gregory William Fleming William Gibson Thomas Paterson Harold Thorby |

| Preceded by | William McWilliams |

| Succeeded by | Archie Cameron |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Cowper | |

|

In office 13 December 1919 – 9 December 1961 | |

| Preceded by | John Thompson |

| Succeeded by | Frank McGuren |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

8 August 1880 Grafton, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died |

20 December 1961 (aged 81) Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Political party | Country Party |

| Spouse(s) |

Ethel Page Jean Page |

| Children | 5 |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

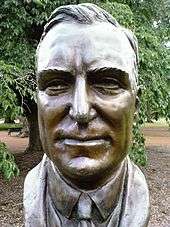

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page, GCMG, CH (8 August 1880 – 20 December 1961) was an Australian politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Australia in 1939. With 41 years, 361 days in Parliament, he is the third-longest serving federal parliamentarian in Australian history, behind only Billy Hughes and Philip Ruddock.[1]

Early life

Born in Grafton, New South Wales, Page was educated at Sydney Boys High School and the University of Sydney, where he initially enrolled in an arts degree, aged 14, before winning a scholarship at the end of the year and transferring to medicine.[2] Page graduated in medicine at the top of his year in 1900.[2][3]

Pre-political career

After graduating from university, Page worked at Sydney's Royal Prince Alfred Hospital as a house surgeon in 1901–1902 and a pathologist thereafter.[2] At Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, he met Ethel Blunt, a nurse, whom he married in 1906.[2]

In 1903, Page joined a private practice in Grafton; and, in 1904, he became one of the first people in the country to own a car.[4] He practised in Sydney and Grafton before joining the Australian Army as a medical officer in the First World War, serving in Egypt.[5]

After the war, Page went into farming and was elected Mayor of Grafton.[6]

Political career

In 1919 Page was elected to the House of Representatives from Cowper in northeastern New South Wales. He ran as a candidate of the Farmers and Settlers Association of New South Wales, one of several farmers' groups that won seats in that election. Shortly before parliament opened in 1920, the Farmers and Settlers Association merged with several other rural-based parties to form the Country Party. He became the party's leader in 1921, ousting William McWilliams. The young party found itself with the balance of power in the House after the 1922 election. The Nationalist government of Billy Hughes lost its majority, and could not govern without Country Party support. However, the Country Party had been formed partly due to discontent with Hughes' rural policy, and Page's animosity toward Hughes was such that he would not even consider supporting him. He demanded Hughes' resignation as the price for beginning negotiations with the Nationalists. As the Country Party was the Nationalists' only politically realistic coalition partner, Hughes stood down.[7]

Page then began negotiations with Hughes' successor as leader of the Nationalists, Stanley Bruce. His terms were stiff; he wanted his Country Party to have five seats in an 11-man cabinet, including the post of Treasurer and the second rank in the ministry for himself. These demands were unprecedented for a prospective junior coalition partner in a Westminster system, and especially so for such a new party. Nonetheless, Bruce agreed rather than force another election.[7][8] For all intents and purposes, Page was the first Deputy Prime Minister of Australia (a title that did not officially exist until 1968). Since then, the leader of the Country/National Party has been the second-ranking member in nearly every non-Labor government.

On 30 January 1924, as Acting Prime Minister, Page chaired the first meeting of Federal Cabinet ever held in Canberra, at Yarralumla House.[9][10] This was still three years before the opening of Parliament House and Canberra becoming the National Capital.

Page continued his professional medical practice. On 22 October 1924, he had to tell his best friend, Thomas Shorten Cole (1870–1957), the news that his wife Mary Ann Crane had just died on the operating table from complications of intestinal or stomach cancer, reputed by their daughter Dorothy May Cole to be "the worst day of his life".

He was a strong believer in orthodox finance and conservative policies, except where the welfare of farmers was concerned: then he was happy to see government money spent freely. He was also a "high protectionist": a supporter of high tariff barriers to protect Australian rural industries.[8][11]

The Bruce-Page government was heavily defeated by Labor in 1929 (with Bruce losing his own seat), and Page went into opposition. In 1931, a group of dissident Labor MPs led by Joseph Lyons merged with the Nationalists to form the United Australia Party under Lyons' leadership. Lyons and The UAP–Country Coalition won a comprehensive victory in the 1931 election. However, the UAP was in a strong enough position (only four seats short of a majority) that Lyons was able to form an exclusively UAP minority government with confidence and supply support from the Country Party—to date, the last time that the party has not had any posts in a non-Labor government. In 1934, however, the UAP suffered an eight-seat swing, forcing Lyons to take the Country Party back into his government in a full-fledged Coalition. Page became Minister for Commerce. He was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) in the New Year’s Day Honours of 1938.[12] While nine Australian Prime Ministers were knighted (and Bruce was elevated to the peerage), Page is the only one who was knighted before becoming Prime Minister.

Prime Minister

When Lyons died suddenly in 1939, the Governor-General Lord Gowrie appointed Page as caretaker Prime Minister. He held the office for three weeks until the UAP elected former deputy leader Robert Menzies as its new leader, and hence Prime Minister.[13]

Page had been close to Lyons, but disliked Menzies, whom he charged publicly with having been disloyal to Lyons. When Menzies was elected UAP leader, Page refused to serve under him, and made an extraordinary personal attack on him in the House, accusing him not only of ministerial incompetence but of physical cowardice (for failing to enlist during World War I). His party soon rebelled, though, and Page was deposed as Country Party leader in favour of Archie Cameron.[13]

In 1940 Page and Menzies patched up their differences for the sake of the war effort, and Page returned to the cabinet as Minister for Commerce.[8] Nevertheless, Page's accusations were not forgotten and were occasionally raised in parliament by Menzies' opponents (notably Eddie Ward). In 1941, the government fell; and Page spent the eight years of the Curtin and Chifley Labor governments on the opposition backbench.[14] He was made a Companion of Honour (CH) in June 1942.[15]

New states

In 1949, Page put forward a discussion paper on the redrawing of state boundaries. He proposed that Australia would be divided into 12 states. Queensland would be split into four states: Eden–Monaro and East Gippsland would become another state, Mount Gambier to Mildura and Cape Otway another state, and the Northern Territory divided into two.[16] Page had a particular interest in forming a new state of New England, in his own area of northeast New South Wales.

Return to the ministry

Menzies returned to the Prime Ministership in 1949, and Page was made Minister for Health. He held this post until 1956, when he was 76, then retired to the backbench.[17] Upon the death of Billy Hughes in October 1952, Page became the Father of the House of Representatives and Father of the Parliament.

Later life and death

Page was the first Chancellor of the University of New England, which was established in 1954.[17]

By the 1961 election, Page was gravely ill, suffering from lung cancer. Although he was too sick to actively campaign, Page refused to even consider retiring from Parliament and soldiered on for his 17th general election. In one of the great upsets of Australian electoral history, he lost his seat to Labor challenger Frank McGuren, whom he had defeated soundly in 1958. Page had gone into the election holding Cowper with what appeared to be an insurmountable 11-point majority, but McGuren managed to win the seat on a swing of 13%.

Page had campaigned sporadically before going to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney for emergency surgery. He went comatose a few days before the election and never regained consciousness. He died on 20 December, 11 days after the election, without ever knowing that he had been defeated.[8][18]

Page had represented Cowper for just four days short of 42 years, making him the longest-serving Australian federal parliamentarian who represented the same seat throughout his career. Only Billy Hughes and Philip Ruddock have served in Parliament longer than Page, but Hughes represented four different seats in two states while Ruddock has represented three seats in New South Wales.

Personal life

Page and his wife Ethel had five children: a daughter Mary born in 1909 and four sons. Ethel Page died in 1958.

On 20 July 1959, Page married his secretary, Jean Thomas.[19] The second Lady Page, died on 20 June 2011.[20] Page's grandson, Don Page, was a National MP in the NSW Parliament and served as Deputy Leader of the NSW Nationals from 2003 to 2007. Another grandson is Canberra poet Geoff Page. His nephew was Robert Page, a soldier and war hero.

Earle Charles Page

Page's oldest son, Earle Charles Page, was born in 1911 at South Grafton and attended Newington College (1922–1927), during the headmastership of the Rev Dr Charles Prescott.[21] At Newington, he won the Wigram Allen Scholarship in 1927, awarded by Sir George Wigram Allen, for general proficiency, with Dave Cowper receiving it for classics and Bill Morrow for mathematics in the same year.[22] In 1932, Page graduated in veterinary science from the University of Sydney.[23]

Earle Charles Page played Rugby Union and was selected for Combined Australian Universities and, as a reserve, for NSW.

Earle Charles Page was managing a rural property for his father at the time of his death in 1933 by lightning strike.[24]

The other Pages boys were Donald (b. 1912), Iven (b. 1914) and Douglas (b. 1916).

Honours

- The Canberra suburb of Page is named after him, as is the House of Representatives Division of Page.

- Earle Page College, a residential college of the University of New England, was founded in his honour, and is the venue for the Earle Page Annual Politics Dinner, which has had numerous prominent national and international guest lecturers.

- In 1957, a new building at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital was opened by Page and named the Page Chest Pavilion.

- In 1975 he was honored on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post.[25]

References

- ↑ Davey, Paul. "Our history of achievement". The Nationals. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 National Archives of Australia. "Australia's Prime Minister". Australian Government.

- ↑ Page, Donald (25 November 1993). "Statesman, Humanitarian, Patriot" (PDF).

- ↑ "Earle Page, Early years". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "First World War Service Record – Earl Page". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Earle Page, South Grafton Council 1913–19". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- 1 2 "Earle Page, Member for Cowper 1919". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Bridge, Carl (1988). "Page, Sir Earle Christmas Grafton (1880–1961)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia, Australia's Prime Ministers: Timeline. Retrieved 14 December 2015

- ↑ Trove NLA, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1924. Retrieved 14 December 2015

- ↑ "Earle Page, Deputy Prime Minister 1923–29". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "It's an Honour – GCMG". Itsanhonour.gov.au. 1 January 1938. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Earle Page, In office". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Earle Page, In Opposition 1941–49". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "It's an Honour – CH". Itsanhonour.gov.au. 26 June 1942. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ Horsham Times 18 August 1949

- 1 2 "Earle Page, Minister for Health 1949–56". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Earle Page, Backbencher 1956–61". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ Bridge, Carl. "Biography – Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page at". adb.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 July 2011

- ↑ Newington College Register of Past Students 1863–1998 (Sydney, 1999), p 150

- ↑ Newington College Register of Past Students 1863–1998 (Sydney, 1999) Part 2 – The Lists

- ↑ Alumni Sidneienses Retrieved 9 July 2013

- ↑ "Earle Page's Son". Gilgandra Weekly and Castlereagh (NSW: 1929–1941). NSW: National Library of Australia. 19 January 1933. p. 4. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "Australian postage stamp". Australian Stamp and Coin Company. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

Further reading

- Hughes, Colin A (1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.12. ISBN 0-19-550471-2

- In their autobiographies Ann (Mozley) Moyal and Ulrich Ellis wrote of their experience of working with Page.[1] Both had helped Page with his autobiography Truant Surgeon: The Inside Story of Forty Years of Australian Political Life (Angus & Robertson, 1963).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Earle Page. |

- "Earle Page". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- "Earle Page". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- Bridge, Carl (1988). "Page, Sir Earle Christmas Grafton (1880–1961)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

| Parliament of Australia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Thomson |

Member for Cowper 1919–1961 |

Succeeded by Frank McGuren |

| Preceded by Billy Hughes |

Father of the House of Representatives 1952–1961 |

Succeeded by Eddie Ward |

| Father of the Parliament 1952–1961 | ||

| Party political offices | ||

| New political party | Leader of the Country Party 1922–1939 |

Succeeded by Archie Cameron |

| New title | Federal President of the Country Party 1926–1961 |

Succeeded by William Moss |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Stanley Bruce |

Treasurer of Australia 1923–1929 |

Succeeded by E G Theodore |

| Preceded by Frederick Stewart |

Minister for Commerce 1934–1939 |

Succeeded by George McLeay |

| Preceded by Billy Hughes |

Minister for Health 1937–1938 |

Succeeded by Harry Foll |

| Preceded by Archie Cameron |

Minister for Commerce 1940–1941 |

Succeeded by William Scully |

| Preceded by Nick McKenna |

Minister for Health 1949–1956 |

Succeeded by Donald Cameron |

| Academic offices | ||

| New title | Chancellor of the University of New England 1954–1960 |

Succeeded by Phillip Wright |

- ↑ Moyal, Ann. Breakfast with Beaverbrook: memoirs of an independent woman (Hale & Iremonger, 1995) and Ulrich Ellis A Pen in Politics (Gininderra Press, 2007).