Hans Sloane

| Sir Hans Sloane, Bt, PRS | |

|---|---|

Sir Hans Sloane | |

| Born |

16 April 1660 Killyleagh, County Down, Ireland |

| Died |

11 January 1753 (aged 92) Chelsea, London, Great Britain |

| Resting place | Chelsea Old Church |

| Nationality | British, of Irish birth |

| Known for |

Physician Philanthropist Entrepreneur Investor Chelsea Physic Garden British Museum[1] President of the Royal Society Sloane Square Sloane's drinking chocolate |

| Notable awards | Fellow of the Royal Society (1685) |

| Spouse | Elisabeth Sloane (née Langley) |

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, PRS (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753) was an Irish born British physician, naturalist and collector, notable for bequeathing his collection to the nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Museum. His name was later used for streets and places such as Hans Place, Hans Crescent and Sloane Square in London, and also to Sir Hans Sloane Square in his birthplace, Killyleagh.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

Early life

Sloane was born on 16 April 1660 at Killyleagh in County Down, in the colonial Protestant Plantation of Ulster in the North of Ireland. He was the seventh son of Alexander Sloane (died 1666), agent for James Hamilton, second Viscount Claneboye and later first Earl of Clanbrassil. Sloane's family had migrated from Ayrshire in Scotland, but settled in the north of Ireland under James I. His father died when he was six years old.

As a youth, Sloane collected objects of natural history and other curiosities. This led him to the study of medicine, which he went to London, where he studied botany, materia medica, surgery and pharmacy. His collecting habits made him useful to John Ray and Robert Boyle. After four years in London he travelled through France, spending some time at Paris and Montpellier, and stayed long enough at the University of Orange-Nassau[1] to take his MD degree there in 1683. He returned to London with a considerable collection of plants and other curiosities, of which the former were sent to Ray and utilised by him for his History of Plants.

Voyage to Jamaica

Sloane was elected to the Royal Society in 1685.[9] At the same time attracted the notice of Thomas Sydenham, who gave him valuable introductions to practice. In 1687, he became a fellow of the College of Physicians, and the same year went to Jamaica aboard HMS Assistance as physician in the suite of the new Governor of Jamaica, the second Duke of Albemarle.[9] Jamaica was fast emerging as a source of immense profit to British merchants based on the cultivation of sugar and other crops by the forced labor of imported African slaves.

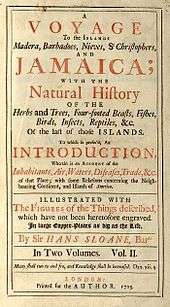

However, Albemarle died in Jamaica the next year, so that Sloane's visit lasted only fifteen months; during that time he noted about 800 new species of plants, which he catalogued in Latin in 1696; he later wrote of his visit in two lavishly illustrated folio volumes (1707 – 1725).[9] He became secretary to the Royal Society in 1693, and edited the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society for twenty years.

Sloane married Elizabeth Langley Rose, the widow of Fulke Rose of Jamaica, and daughter of alderman John Langley. They had three daughters, Mary, Sarah and Elizabeth.[lower-alpha 1] They also had one son, Hans. Of the four children only Sarah and Elizabeth survived infancy. Sarah married George Stanley of Paultons and Elizabeth married Charles Cadogan, the future Second Baron Cadogan. Income from the sugar produced by enslaved African laborers on Elizabeth's plantations at an area known as Sixteen Mile Walk fed the family fortunes in London and, together with Sloane's medical revenue and London property investments, gave him the wealth to collect on a vast scale.[10]

Sloane encountered cacao while he was in Jamaica, where the locals drank it mixed with water, though he is reported to have found it nauseating. Many recipes for mixing chocolate with spice, eggs, sugar and milk were in circulation by the seventeenth century. After returning from Jamaica, Sloane may have devised his own recipe for mixing chocolate with milk, though if so, he was not the first. By the 1750s, a Soho grocer named Nicholas Sanders claimed to be selling Sloane's recipe as a medicinal elixir, perhaps making 'Sir Hans Sloane's Milk Chocolate' the first brand-name milk chocolate. By the nineteenth century, the Cadbury Brothers sold tins of drinking chocolate whose trade cards also invoked Sloane's recipe.[11][12]

Society Physician

His practice as a physician among the upper classes was large, fashionable and lucrative. He served three successive sovereigns, Queen Anne, George I and George II. In the pamphlets written concerning the sale by William Cockburn of his secret remedy for dysentery and other fluxes, it was stated for the defence that Sloane himself did not disdain the same kind of professional conduct; and some colour is given to that charge by the fact that his only medical publication, an Account of a Medicine for Soreness, Weakness and other Distempers of the Eyes (London, 1745) was not given to the world until its author was in his eighty-fifth year and had retired from practice.

In 1716, Sloane was created a baronet, making him the first medical practitioner to receive a hereditary title. In 1719 he became president of the Royal College of Physicians, holding the office for sixteen years. In 1722, he was appointed physician-general to the army, and in 1727 first physician to George II. In 1727 he succeeded Sir Isaac Newton as president of the Royal Society; he retired from it at the age of eighty. He was a founding governor of London's Foundling Hospital, the nation's first institution to care for abandoned children.

The British Museum and Chelsea Physic Garden

Sloane's fame is based on his judicious investments rather than what he contributed to the subject of natural science or even of his own profession. His purchase of the manor of Chelsea, London in 1712, provided the grounds for the Chelsea Physic Garden. His great stroke as a collector was to acquire in 1701 (by bequest, conditional on paying of certain debts) the cabinet of William Courten, who had made collecting the business of his life.

When Sloane retired in 1741, his library and cabinet of curiosities, which he took with him from Bloomsbury to his house in Chelsea, had grown to be of unique value. He had acquired the extensive natural history collections of William Courten, Cardinal Filippo Antonio Gualterio, James Petiver, Nehemiah Grew, Leonard Plukenet, the Duchess of Beaufort, the rev. Adam Buddle, Paul Hermann, Franz Kiggelaer and Herman Boerhaave. On his death on 11 January 1753 he bequeathed[1] his books, manuscripts, prints, drawings, flora, fauna, medals, coins, seals, cameos and other curiosities to the nation, on condition that parliament should pay his executors £20,000, far less than the value of the collection. The bequest was accepted on those terms by an act passed the same year, and the collection, together with George II's royal library, etc., was opened to the public at Bloomsbury as the British Museum in 1759. A significant proportion of this collection was later to become the foundation for the Natural History Museum.

He also gave the Apothecaries' Company the land of the Chelsea physic garden, which they had rented from the Chelsea estate since 1673.

Death

Hans Sloane was buried on 18 January 1753[13] at Chelsea Old Church with the following memorial:

"To the memory of Sir Hans Sloane, Bart, President of the Royal Society, and of the College of Physicians; who in the year of our Lord 1753, the 92d of his age, without the least pain of body and with a conscious serenity of mind, ended a virtuous and beneficent life. This monument was erected by his two daughters Eliza Cadogan and Sarah Stanley"

Legacy

His grave is shared with his wife Elisabeth[lower-alpha 2] who died in 1724. Sloane Square, Sloane Street and Sloane Gardens in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea are named after Sir Hans as is the moth Urania sloanus. His first name is given to Hans Street, Hans Crescent, Hans Place and Hans Road, all of which are also situated in the Royal Borough. Carl Linnaeus named the plant genus Sloanea after him.

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 Anon (1969). "Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) founder of the British Museum". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 207 (5): 943–910. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03150180073016. PMID 4884737.

- ↑ Ford, J. M. (2003). "Medical Memorial. Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753)". Journal of medical biography. 11 (3): 180. PMID 12870044.

- ↑ McIntyre, N. (2001). "Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753)". Journal of medical biography. 9 (4): 235. PMID 11718127.

- ↑ Dunn, P. M. (2001). "Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) and the value of breast milk". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 85 (1): F73–F74. doi:10.1136/fn.85.1.F73. PMC 1721277

. PMID 11420330.

. PMID 11420330. - ↑ Ravin, J. G. (2000). "Sir Hans Sloane's contributions to ocular therapy, scientific journalism, and the creation of the British Museum". Archives of ophthalmology. 118 (11): 1567–1573. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.11.1567. PMID 11074814.

- ↑ Mason, A. S. (1993). "Hans Sloane and his friends. The FitzPatrick Lecture 1993". Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 27 (4): 450–455. PMID 8289170.

- ↑ Nelson, E. C. (1992). "Charles Lucas' letter (1736) to Sir Hans Sloane about the natural history of the Burren, County Clare". Journal of the Irish Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons. 21 (2): 126–131. PMID 11616186.

- ↑ Ober, W. B. (1968). "Sir Hans Sloane, M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.S. (1660-1753) and the British Museum". New York state journal of medicine. 68 (11): 1422–1430. PMID 4872002.

- 1 2 3 Carter, Harold B. (July 1995). "The Royal Society and the Voyage of HMS Endeavour 1768-71". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. London, UK: The Royal Society. 49 (2): 245–260. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1995.0026. JSTOR 532013. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Brooks 1954.

- ↑ Delbourgo, James (2011). "Sir Hans Sloane's Milk Chocolate and the Whole History of the Cacao". Social Text.

- ↑ "About Sir Hans Sloane". The Natural History Museum. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ↑ Preston 1854, p. 13-.

Sources

- Brooks, Eric St. John (1954). Sir Hans Sloane: the great collector and his circle. Batchworth Press.

- Preston, Henry C. (1854). The Life of North American Insects: Illustrated by Numerous Colored Engravings and Narratives. Sayles, Miller and Simons, printers.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- De Beer, Sir Gavin (1953). Sir Hans Sloane and the British Museum. London: Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, Jack A. (Oct 1980). "Sir Hans Sloane and Abbé Jean Paul Bignon: Notes on Collection Building in the Eighteenth Century". The Library Quarterly. 50 (4): 475–482. doi:10.1086/601019. JSTOR 4307275.

- Lyons, J. 2008. p. 53 – 54. The Life and Times of a famous Ulsterman. Copeland Report for 2008. Copeland Bird Observatory

- Weld, Charles Richard (1848). A history of the Royal Society: with memoirs of the presidents. Vol. 1. London: Parker. p. 450.

- Munk, William (1861). The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London; Compiled from the Annals of the College and from Other Authentic Sources. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. [Ab. 4.] [Dr:] [Harrison]. p. 466.

- Lundy, Darryl, Sir Hans Sloane, 1st and last Baronet, The Peerage

External links

- About Hans Sloane, Natural History Museum, London

- "Index to the Sloane manuscripts in the British Museum", in the British Museum in various formats, at Archive.org

- A Voyage… on Botanicus

- Catalogus Plantarum...on Botanicus

- The Sloane Printed Books Catalogue

- Sloane Correspondence Online

- Sloane Letters Blog

- "Voyage to the Islands: Hans Sloane, Slavery and Scientific Travel in the Caribbean", John Carter Brown Library online exhibition

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Hans Sloane |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hans Sloane. |

| Baronetage of Great Britain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by New creation |

Baronet (of Chelsea) 1716 – 1753 |

Succeeded by Title extinct |

| Cultural offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Isaac Newton |

President of the Royal Society 1727 – 1741 |

Succeeded by Martin Folkes |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by John Bateman |

President of Royal College of Physicians 1719 – 1735 |

Succeeded by Thomas Pellett |