Sloss Furnaces

|

Sloss Blast Furnace Site | |

|

Sloss Furnaces, Birmingham, in July 2016 | |

| |

| Location |

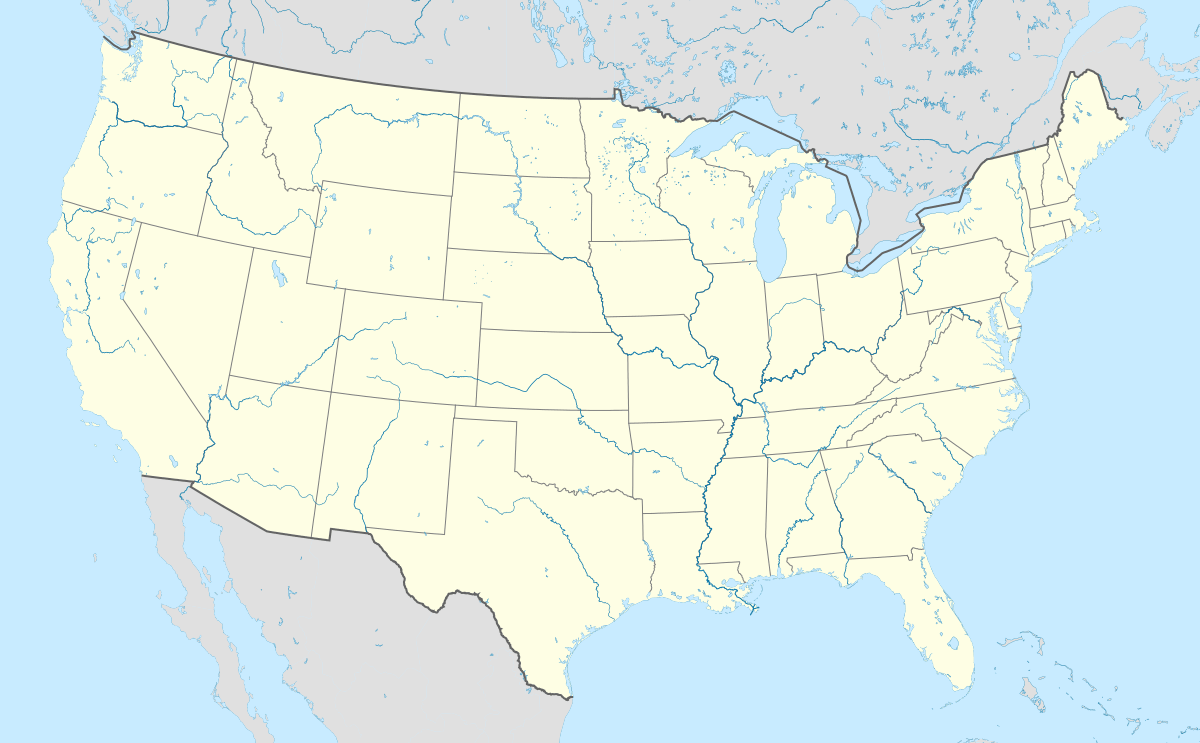

1st Ave. at 32nd St. Birmingham, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°31′14.36″N 86°47′28.70″W / 33.5206556°N 86.7913056°WCoordinates: 33°31′14.36″N 86°47′28.70″W / 33.5206556°N 86.7913056°W |

| Built | 1881 |

| Architect | James W. Sloss; Et al. |

| NRHP Reference # | 72000162 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 22, 1972[1] |

| Designated NHL | May 29, 1981[2] |

Sloss Furnaces is a National Historic Landmark in Birmingham, Alabama in the United States. It operated as a pig iron-producing blast furnace from 1882 to 1971. After closing it became one of the first industrial sites (and the only blast furnace) in the U.S. to be preserved and restored for public use. In 1981 the furnaces were designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of the Interior.[2][3]

The site currently serves as an interpretive museum of industry and hosts a nationally recognized metal arts program. It also serves as a concert and festival venue. Construction is also underway on a new $10 million visitors center. The furnace site, along a wide strip of land reserved in Birmingham's original city plan for railroads and industry, is also part of a proposed linear park through downtown Birmingham. An annual Halloween haunted attraction called "Sloss Fright Furnace" is held at the site.[4]

History

Colonel James Withers Sloss was one of the founders of Birmingham, helping to promote railroad development in Jones Valley, Alabama and participating in the Pratt Coke and Coal Company, one of the new city's first manufacturers. In 1880 he formed his own company, the Sloss Furnace Company, and began construction of Birmingham's first blast furnace on 50 acres (202,000 m²) of land donated by the Elyton Land Company for industrial development. The engineer in charge of construction was Harry Hargreaves, a former student of English inventor Thomas Whitwell. The two Whitwell-type furnaces were 60 feet (18 m) tall and 18 feet (5.4 m) in diameter. The first blast was initiated in April 1882. The facility produced 24,000 tons of high quality iron during its first year of operation. Sloss iron won a bronze medal at the Southern Exposition held in 1883 at Louisville, Kentucky.

In 1886 Sloss retired and sold the company to a group of investors who reorganized it in 1899 as the Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company. New blowers were installed in 1902, new boilers in 1906 and 1914 and the furnaces completely rebuilt with modern equipment between 1927 and 1931. In 1909 James Pickering Dovel had become the superintendent of construction. For the next twenty-one years, Sloss was Dovel's workshop for invention. He developed gas cleaning equipment, modified the design of the furnaces, and improved the linings of the furnaces. In all, some seventeen patents are credited to Dovel. Sloss's No. 2 Furnace, rebuilt in 1927, included many of these inventions, earning Dovel and Sloss a national reputation for innovation.[5] Through this aggressive campaign of modernization and expansion, including furnace and mining and quarrying operations all around Jefferson County, Sloss-Sheffield became the second largest seller of pig-iron in the district and among the largest in the world. During this period the company built 48 small cottages for black workers near the downtown furnace — a community that became known as "Sloss Quarters" or just "the quarters".

In 1952, the Sloss Furnaces were acquired by the U.S. Pipe and Foundry Company, and sold nearly two decades later in 1969 to the Jim Walter Corp. The Birmingham area had been suffering from a serious air pollution problem during the 1950s and 1960s due to the iron and steel industry there, and Federal legislation such as the U.S. Clean Air Act encouraged the closure of older and out-of-date smelting works. Also, by the early 1960s, higher-yielding brown ores from other regions were feeding the blast furnaces.[6]

The Jim Walter company closed the furnaces two years later, and then donated the property to the Alabama State Fair Authority for possible development as a museum of industry. The authority determined that redevelopment was not feasible and made plans to demolish the furnaces. Local preservationists formed the Sloss Furnace Association to lobby for preservation of this site, which is of central importance to the history of Birmingham. In 1976 the site was documented for the Historic American Engineering Record and its historic significance was detailed in a study commissioned by the city. Birmingham voters approved a $3.3 million bond issue in 1977 to preserve the site. This money went toward stabilization of the main structures and the construction of a visitor's center and the establishment of a metal arts program.

In February 2009 Sloss became the new home of the SLSF 4018 steam locomotive, which was relocated from Birmingham's Fair Park.

Present use

Sloss is currently used to hold metal arts classes, a barbecue cookoff, Muse of Fire shows, and concerts. Being a reportedly haunted location, it is also an annual Halloween haunted attraction. Once a year, Sloss Furnaces hosts a "Ghost Tour" based on a story written by Alabama folklorist Kathryn Tucker Windham. Sloss Furnaces has been investigated by Ghost Adventures from Travel Channel "Ghost Asylum" from Destination America and also by Syfy's Ghost Hunters. The story of Sloss' preservation and modern use was documented in Alabama Public Television's Sloss: Industry to Art.[7]

For many years Sloss Furnaces has been used as a haunted house attraction during the Halloween season. The event is termed "Sloss Fright Furnace".

In June 2012 a formal groundbreaking ceremony was held at the site, signaling the beginning of construction on a new 16,000 square foot Visitors and Education Center to be located on the southwest corner of the furnace site.[8] The new complex, funded jointly by the City of Birmingham and the Sloss Foundation, is expected to host educational exhibits relevant to the site's history, administrative offices, as well as additional multipurpose space for public events. The facility improvements are expected to be in line with an ongoing project within the city to construct new "greenway" spaces in the downtown area, possibly linking several popular city venues in the future.[9]

Gallery

Ladder and window at Sloss Furnaces

Ladder and window at Sloss Furnaces Metalwork at Sloss Furnaces

Metalwork at Sloss Furnaces Gridiron supports atop a catwalk at Sloss Furnaces

Gridiron supports atop a catwalk at Sloss Furnaces Impressionistic rust pattern at Sloss Furnaces

Impressionistic rust pattern at Sloss Furnaces Rusted machinery at Sloss Furnaces

Rusted machinery at Sloss Furnaces Rusted machinery at Sloss Furnaces

Rusted machinery at Sloss Furnaces

See also

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Sloss Blast Furnaces". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ George R. Adams (April 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Sloss Blast Furnaces" (PDF). National Park Service. and Accompanying 7 photos, from 1978 and 1971. (1.92 MB)

- ↑ Sloss Fright Furnace

- ↑ http://www.historicalmarkerproject.com/markers/HMTBK_the-gas-system_Birmingham-AL.html

- ↑ Lewis, W. David (1994). Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Univ. of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0708-7.

- ↑ Windham, Kathryn Tucker (1987). The Ghost in the Sloss Furnaces. Birmingham, Alabama, Birmingham Historical Society. ISBN 0-317-65100-5.

- ↑ Stelter, Linda. "Birmingham's Sloss Furnaces prepares for groundbreaking for new visitors center". The Birmingham News. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ Tomberlin, Michael. "New Sloss Furnaces visitor center in Birmingham to open in 2012". The Birmingham News. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

External links

- Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

- Sloss Metal Arts

- Sloss Fright Furnace - Halloween attraction

- Ghost at Sloss Furnaces

- Sloss Furnaces article in the Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Alabama Public Television's Sloss: Industry to Art - Documentary