Stapedectomy

| Stapedectomy | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

| ICD-9-CM | 19.1 |

A stapedectomy is a surgical procedure of the middle ear performed in order to improve hearing.

If the stapes footplate is fixed in position, rather than being normally mobile, then a conductive hearing loss results. There are two major causes of stapes fixation. The first is a disease process of abnormal mineralization of the temporal bone called otosclerosis. The second is a congenital malformation of the stapes.

In both of these situations, it is possible to improve hearing by removing the stapes bone and replacing it with a micro prosthesis - a stapedectomy, or creating a small hole in the fixed stapes footplace and inserting a tiny, piston-like prosthesis - a stapedotomy. The results of this surgery are generally most reliable in patients whose stapes has lost mobility because of otosclerosis. Nine out of ten patients who undergo the procedure will come out with significantly improved hearing while less than 1% will experience worsened hearing acuity or deafness. Successful surgery usually provides an increase in hearing acuity of about 20 dB. That is as much difference as having your hands over both ears, or not. However, most of the published results of success fall within the speech frequency of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz and 2000 Hz; poorer results are typically obtained in the high frequencies, but these are normally less hampered by otosclerosis in the first place.[1]

Indications

Indications of stapedectomy:

- Conductive hearing loss (due to fixation of stapes).

- Air bone gap of at least 30 dB.

- Presence of Carhart's notch in the audiogram of a patient with conductive hearing loss (relative)

- Good cochlear reserve as assessed by the presence of good speech discrimination.

Contraindications

Contraindications for stapedectomy:

- Poor general condition of the patient.

- Only hearing ear.

- Poor cochlear reserve as shown by poor speech discrimination scores

- Patient with tinnitus and vertigo

- Presence of active otosclerotic foci (otospongiosis) as evidenced by a positive flemmingo sign.

- Conductive deafness due to Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

Complications

Complications of stapedectomy:

- Facial palsy

- Vertigo in the immediate post op period

- Vomiting

- Perilymph gush

- Floating foot plate

- Tympanic membrane tear

- Dead labyrinth

- Perilymph fistula

- Labyrinthitis

- Granuloma (Reparative)

- Tinnitus

When a stapedectomy is done in a middle ear with a congenitally fixed footplate, the results may be excellent but the risk of hearing damage is greater than when the stapes bone is removed and replaced (for otosclerosis). This is primarily due to the risk of additional anomalies being present in the congenitally abnormal ear. If high pressure within the fluid compartment that lies just below the stapes footplate exists, then a perilymphatic gusher may occur when the stapes is removed. Even without immediate complications during surgery, there is always concern of a perilymph fistula forming postoperatively.

In 1995, Glasscock et al. published a 25-year single-centre review of over 900 patients who underwent stapedectomy and stapedotomy and found complications rates as follows: reparative granuloma 1.3%, tympanic membrane perforation 1.0%, total sensorineural hearing loss 0.6%, partial sensorineural hearing loss 0.3%, and vertigo 0.3%. In this series, there was no incidence of facial nerve paralysis or tinnitus.[2]

Stapedotomy

A modified stapes operation, called a stapedotomy, is thought by many otologic surgeons to be safer and reduce the chances of postoperative complications. In stapedotomy, instead of removing the whole stapes footplate, a tiny hole is made in the footplate - either with a microdrill or with a laser,[3] and a prosthesis is placed to touch this area with movement of the tympanic membrane. This procedure can be further improved by the use of a tissue graft seal of the fenestra, which is now common practice.[4]

Laser stapedotomy is a well-established surgical technique for treating conductive hearing loss due to otosclerosis. The procedure creates a tiny opening in the stapes (the smallest bone in the human body) in which to secure a prosthetic. The CO2 laser allows the surgeon to create very small, precisely placed holes without increasing the temperature of the inner ear fluid by more than one degree, making this an extremely safe surgical solution. The hole diameter can be predetermined according to the prosthesis diameter. Treatment can be completed in a single operation visit using anesthesia, normally followed by one or two nights' hospitalization with subsequent at-home recovery time a matter of days or weeks.

Stapedectomy vs. stapedotomy

Comparisons have shown stapedotomy to yield either as good[5] or better[6] results than stapedectomy (measured by hearing improvement and reduction in the air-bone hearing gap, and especially at higher sound frequencies), and to be less prone to complications.[7] In particular, stapedotomy procedure greatly reduces the chance of a perilymph fistula (leakage of cochlear fluid).[4]

Stapedotomy, like stapedectomy, can be successful in the presence of sclerotic adhesions (tissue growths abnormally linking the bones to the tympanic cavity), provided the adhesions are removed during surgery. However, the adhesions may recur over time. The stapedotomy method is not applicable in those relatively rare cases that involve scleroris of the entire ossicular chain.

Because it is a simpler and safer procedure, stapedotomy is normally preferred to stapedectomy in the absence of predictable complications. However, the success rate of either surgery depends greatly on the skill and the familiarity with the procedure of the surgeon.[4] Furthermore, a major success factor in both surgeries is correctly determining the length of the prosthesis.[8][9]

History

The world's first stapedectomy is credited to Dr. John J.Shea Jr. who performed it in May 1956 on a 54-year-old housewife who could no longer hear even with a hearing aid.[10] Significant contributions to modern stapedectomy techniques were then made by the late Dr. Antonio De La Cruz of the House Ear Institute in Los Angeles; by the late Professor Henri André Martin of the Hôpital Edouard Herriot in Lyon, France, including calibrated platinotomy (stapes footplate rather than whole surgery) and trans-footplate piston surgery that also paved the way for modern stapedotomy;[11] and by the late Dr. Jean-René Causse of the eponymous clinic in Béziers, France, who pioneered the use of Teflon piston prostheses (also critical progress for stapedotomy) and, with his late son Dr. Jean-Bernard Causse, the reattachment of the stapedius muscle alongside the use of veinous grafts.[12][13]

Anatomy gallery

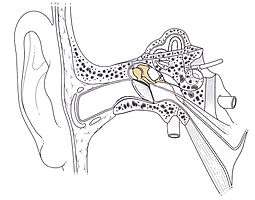

Location of the ossicular chain in the ear

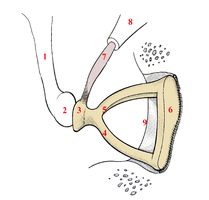

Right-ear stapes

Stapes: Relative size

Footnotes

- ↑ R, Raman (1983), "Poor High Frequency Results Following Total Stapedectomy Theoretical Considerations", Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 35 (1)

- ↑ Twenty-five years of experience with stapedectomy. Glasscock ME 3rd, Storper IS, Haynes DS, Bohrer PS. Laryngoscope. 1995 Sep;105(9 Pt 1):899-904.

- ↑ Perkins, Rodney C. (1980), "Laser Stapedotomy for Otosclerosis", Laryngoscope, 90 (2): 228–241, doi:10.1288/00005537-198002000-00007

- 1 2 3 de Souza; Glassock (2004), Otosclerosis and Stapedectomy, New York, NY: Thieme, ISBN 1-58890-169-6

- ↑ Sedwick JD, Louden CL & Shelton C, Stapedectomy vs stapedotomy: Do you really need a laser? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg., 123(2):177-180, 1997.

- ↑ Motta G, Ruosi M & Motta S, Stapedotomy vs stapedectomy: Comparison of hearing results, Acta Otorhinolaryngologica, 16(2 Suppl 53): 36-41, 1996)

- ↑ Thamjarayakul T, Supiyaphun P & Snidvongs K, Stapes fixation surgery: Stapedectomy versus stapedotomy, Asian Biomedicine, 4(3): 429-434, 2010.

- ↑ Paum PB, Pollak AM & Fisch U., Utricle, saccule and cochlear duct in relation to stapedotomy: A histologic temporal bone study, Ann Oto Rhinol Laryngol, 12, 1991.

- ↑ Fisch U, Commentary - stapedotomy versus stapedectomy, Otology & Neurotology, 30(8): 1166-1167, 2009.

- ↑ "John J. Shea, Jr". Shea Ear Clinic. Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ Lacher, Guy (2004), Necrology: Henri André Martin, 01/21/1918 - 10/16/2004, European Review of ENT (in French), 125 issue 5, p. 332

- ↑ Causse JB, Stapedotomy technique and results, American Journal of Otology, 6(1), 1985.

- ↑ Pulec, Jack L. (February 2002), "Obiruaries: Jean-Rene Causse, MD, February 6, 1910 - December 10, 2001; Jean-Bernard Causse, MD, May 13, 1944 - December 13, 2001", Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, Ear, Nose & Throat Journal

See also

External links

- The LION Foundation's Live International Otolaryngology Network offers annual symposia geared for continuing education of practicing surgeons, and subsequently available via streaming internet.

- Overview of Otosclerosis and Stapedectomy

- Balasubramanian T (2006). "Stapedectomy". Retrieved 2007-07-03. - details of the procedure with pictures

- Amanda Jenner, Lynne Shields PhD ccc-slp "Speech and Language Issues"

- M. Hawthorne, FRCS-ENT Surgeon. "Hearing Impairment and EDS"

- S.O. "blood in the water" McM- "Stapedectomy- complications and pitfalls"

- Instructional Video of a Spapedectomy from Dr. Mark Levenson on YouTube