Rhode Island

Coordinates: 41°42′N 71°30′W / 41.7°N 71.5°W

| State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

|

Nickname(s): The Ocean State Little Rhody[1] | |||||

| Motto(s): Hope | |||||

.svg.png) | |||||

| Official language |

De jure: None De facto: English | ||||

| Demonym | Rhode Islander | ||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Providence | ||||

| Largest metro | Providence metro area | ||||

| Area | |||||

| • Total |

1,214[2] sq mi (3,144 km2) | ||||

| • Width | 37 miles (60 km) | ||||

| • Length | 48 miles (77 km) | ||||

| • % water | 13.9% | ||||

| • Latitude | 41° 09' N to 42° 01' N | ||||

| • Longitude | 71° 07' W to 71° 53' W | ||||

| Population | |||||

| • Total | 1,056,298 (2015 est.)[3] | ||||

| • Density |

1006/sq mi (388/km2) Ranked 2nd | ||||

| • Median household income | $54,619 (16th) | ||||

| Elevation | |||||

| • Highest point |

Jerimoth Hill[4][5] 812 ft (247 m) | ||||

| • Mean | 200 ft (60 m) | ||||

| • Lowest point |

Atlantic Ocean[4] sea level | ||||

| Before statehood | Rhode Island | ||||

| Admission to Union | May 29, 1790 (13th) | ||||

| Governor | Gina Raimondo (D) | ||||

| Lieutenant Governor | Daniel McKee (D) | ||||

| Legislature | |||||

| • Upper house | Senate | ||||

| • Lower house | House of Representatives | ||||

| U.S. Senators |

Jack Reed (D) Sheldon Whitehouse (D) | ||||

| U.S. House delegation |

1: David Cicilline (D) 2: James Langevin (D) (list) | ||||

| Time zone | Eastern: UTC −5/−4 | ||||

| ISO 3166 | US-RI | ||||

| Abbreviations | RI | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

| Footnotes: * Total area is approximately 776,957 acres (3,144 km2) | |||||

| Rhode Island state symbols | |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird |

Rhode Island Red Chicken Gallus gallus domesticus |

| Fish | Striped bass |

| Flower |

Violet Viola sororia |

| Insect |

American burying beetle Nicroforus americanus |

| Mammal | Morgan horse |

| Reptile | Painted turtle |

| Tree |

Red Maple Acer rubrum |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Coffee milk |

| Mineral | Bowenite |

| Motto | Hope |

| Rock | Cumberlandite |

| Ship | Courageous, USS Providence |

| Slogan | Unwind |

| Song | "Rhode Island, It's for Me" |

| Tartan | Rhode Island State Tartan |

| Other | Fruit: Rhode Island Greening |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

|

Released in 2001 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Rhode Island (![]() i/ˌroʊdˈaɪlənd/),[6][7] officially the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,[8] is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. Rhode Island is the smallest in area, the eighth least populous, and the second most densely populated of the 50 U.S. states, following New Jersey. Its official name is also the longest of any state in the Union. Rhode Island is bordered by Connecticut to the west, Massachusetts to the north and east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Island Sound. The state also shares a short maritime border with New York.[9]

i/ˌroʊdˈaɪlənd/),[6][7] officially the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,[8] is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. Rhode Island is the smallest in area, the eighth least populous, and the second most densely populated of the 50 U.S. states, following New Jersey. Its official name is also the longest of any state in the Union. Rhode Island is bordered by Connecticut to the west, Massachusetts to the north and east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Island Sound. The state also shares a short maritime border with New York.[9]

On May 4, 1776, Rhode Island became the first of the Thirteen Colonies to renounce its allegiance to the British Crown,[10] and was the fourth among the newly sovereign states to ratify the Articles of Confederation on February 9, 1778.[11] It boycotted the 1787 convention that drew up the United States Constitution[12] and initially refused to ratify it.[13] On May 29, 1790, Rhode Island became the 13th and last state to ratify the Constitution.[14][15]

Rhode Island's official nickname is "The Ocean State", a reference to the fact that the state has several large bays and inlets that amount to about 14% of its total area.[2] Rhode Island covers 1,214 square miles (3,144 km2), of which 1,045 square miles (2,707 km2) are land.

Origin of the name

Despite its name, most of Rhode Island is located on the mainland of the United States. The official name of the state is State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, which is derived from the merger of two colonies. Rhode Island colony was founded on what is now commonly called Aquidneck Island, the largest of several islands in Narragansett Bay, and included the settlements of Newport and Portsmouth.[16] Providence Plantation was the name of the colony founded by Roger Williams in the area now known as the city of Providence.[17]

It is unclear how Aquidneck Island came to be known as Rhode Island, although there are two popular theories.

- Explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano noted the presence of an island near the mouth of Narragansett Bay in 1524, which he likened to the island of Rhodes (part of modern Greece).[18] Subsequent European explorers were unable to precisely identify the island that Verrazzano had named, but the Pilgrims who later colonized the area assumed that it was Aquidneck.[19]

- A second theory concerns the fact that Adriaen Block passed by Aquidneck during his expeditions in the 1610s, described in a 1625 account of his travels as "an island of reddish appearance" (in 17th-century Dutch "een rodlich Eylande").[20] Historians have theorized that this "reddish appearance" resulted from either red autumn foliage or red clay on portions of the shore.[21][22]

The earliest documented use of the name "Rhode Island" for Aquidneck was in 1637 by Roger Williams. The name was officially applied to the island in 1644 with these words: "Aquethneck shall be henceforth called the Isle of Rodes or Rhode-Island." The name "Isle of Rodes" is used in a legal document as late as 1646.[23][24] Dutch maps as early as 1659 call the island "Red Island" (Roodt Eylant).

Williams was a theologian forced out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Seeking religious and political tolerance, he and others founded Providence Plantation as a free proprietary colony. "Providence" referred to the concept of divine providence, and "plantation" was an English term for a colony. "State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations" is the longest official name of any state in the Union.

2009 contestation of the name

In recent years, the presence of the word plantation in the state's name became a sufficiently contested issue that, on June 25, 2009, the General Assembly voted to hold a general referendum determining whether "and Providence Plantations" would be dropped from the official name. Advocates for excising plantation asserted that the word specifically referred to the British colonial practice of establishing settlements which disenfranchised native people. They argued that the word symbolized, for many Rhode Islanders, a legacy of violent native disenfranchisement, but also of the proliferation of slavery in the colonies and in the post-colonial United States. (Rhode Island abolished slavery in 1652, but the law was not enforced and, by the early 1700s, it was "the epicenter of the North American slave trade", according to the Brown Daily Herald.)[25][26] Advocates for retaining the name argued that plantation was simply an archaic English synonym for colony and bore no relation to slavery. The referendum election was held on November 2, 2010, and the people voted overwhelmingly (78% to 22%) to retain the entire original name.[27]

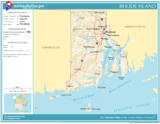

Geography

Rhode Island covers an area of 1,214 square miles (3,144 km2) located within the New England Region, and is bordered on the north and east by Massachusetts, on the west by Connecticut, and on the south by Rhode Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean.[2] It shares a narrow maritime border with New York State between Block Island and Long Island. The mean elevation of the state is 200 feet (61 m). It is only 37 miles (60 km) wide and 48 miles (77 km) long, yet the state has a tidal shoreline on Narragansett Bay and the Atlantic Ocean of 384 miles (618 km).[28]

Rhode Island is nicknamed the Ocean State and has a number of oceanfront beaches. It is mostly flat with no real mountains, and the state's highest natural point is Jerimoth Hill, 812 feet (247 m) above sea level.[29]

Rhode Island has two distinct natural regions. Eastern Rhode Island contains the lowlands of the Narragansett Bay, while Western Rhode Island forms part of the New England Upland. Rhode Island's forests are part of the Northeastern coastal forests ecoregion.[30]

Narragansett Bay is a major feature of the state's topography. There are more than 30 islands within the bay. The largest is Aquidneck Island, shared by the municipalities of Newport, Middletown, and Portsmouth. The second-largest island is Conanicut; the third-largest is Prudence. Block Island lies about 12 miles (19 km) off the southern coast of the mainland and separates Block Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean proper.[31][32]

| Geography of Rhode Island | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Geology

A rare type of rock called Cumberlandite is found only in Rhode Island (specifically in the town of Cumberland) and is the state rock. There were initially two known deposits of the mineral, but since it is an ore of iron, one of the deposits was extensively mined for its ferrous content. The state is underlain by the Avalon terrane and was once part of the micro-continent Avalonia before the Iapetus ocean closed.

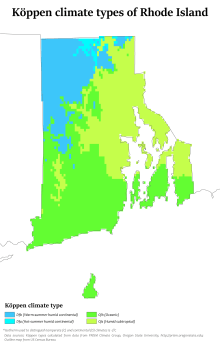

Climate

Rhode Island is on the borderline between humid subtropical and humid continental climates with warm, rainy summers and chilly winters. The highest temperature recorded in Rhode Island was 104 °F (40 °C), recorded on August 2, 1975, in Providence.[33] The lowest recorded temperature in Rhode Island was −23 °F (−31 °C) on February 5, 1996, in Greene.[34] Monthly average temperatures range from a high of 83 °F (28 °C) to a low of 20 °F (−7 °C).[35]

Due to its location in New England, Rhode Island is vulnerable to tropical storms or hurricanes. The 1938 New England hurricane, Hurricane Carol, Hurricane Donna and Hurricane Bob are some examples of hurricanes that have affected the state.

History

Colonial era: 1636–1770

In 1636, Roger Williams was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for his religious views, and he settled at the tip of Narragansett Bay on land granted to him by the Narragansett and Pequot tribes. Both tribes were subservient to the Wampanoag tribe led by Massasoit. He called the site Providence, "having a sense of God's merciful providence unto me in my distress."[36] Eventually, it became a place of religious freedom.

In 1638 (after conferring with Williams), Anne Hutchinson, William Coddington, John Clarke, Philip Sherman, and other religious dissenters settled on Aquidneck Island (then known as Rhode Island), which was purchased from the local natives who called it Pocasset. This settlement was called Portsmouth and was governed by the Portsmouth Compact. The southern part of the island became the separate settlement of Newport after disagreements among the founders.

Samuel Gorton purchased lands at Shawomet in 1642 from the Narragansetts, precipitating a military dispute with the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1644, Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport united for their common independence as the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, governed by an elected council and "president". Gorton received a separate charter for his settlement in 1648, which he named Warwick after his patron.[37]

During King Philip's War (1675–1676), a force of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Plymouth militia under General Josiah Winslow invaded and destroyed the fortified Narragansett Indian village in the Great Swamp in what is now South Kingstown, Rhode Island on December 19, 1675, in response to previous Indian attacks.[38] The Indians referred to this as a massacre. The Wampanoag tribe under war-leader Metacomet, whom the colonists called "King Philip", invaded and burned down several of the towns in the area—including Providence, which was attacked twice.[36] In one of the final actions of the war, Benjamin Church killed King Philip in what is now Bristol, Rhode Island; King Philip's head was put on a pole and stood at the entrance to Plimoth Plantation as a warning to other Indians for years.[39]

The colony was amalgamated into the Dominion of New England in 1686, as King James II attempted to enforce royal authority over the autonomous colonies in British North America. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the colony regained its independence under the Royal Charter. Slaves were introduced at this time, although there is no record of any law legalizing slave-holding. The colony later prospered under the slave trade, distilling rum to sell in Africa as part of a profitable triangular trade in slaves and sugar with the Caribbean.[40]

Revolutionary to Civil War period: 1770–1860

Rhode Island's tradition of independence and dissent gave it a prominent role in the American Revolution. At approximately 2 a.m. on June 10, 1772, a band of Providence residents attacked the grounded revenue schooner Gaspee, burning it to the waterline for enforcing unpopular trade regulations within Narragansett Bay.[41] Rhode Island was the first of the thirteen colonies to renounce its allegiance to the British Crown on May 4, 1776.[42] It was also the last of the thirteen colonies to ratify the United States Constitution on May 29, 1790, once assurances were made that a Bill of Rights would become part of the Constitution.[43] During the Revolution, the British occupied Newport. A combined Franco-American force fought to drive them off Aquidneck Island. Portsmouth was the site of the first African-American military unit, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, to fight for the U.S. in the Battle of Rhode Island of August 29, 1778. The arrival of a French fleet forced the British to scuttle their own ships rather than surrender them to the French. The celebrated march to Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781 ended with the defeat of the British at the Siege of Yorktown and the Battle of the Chesapeake.

Rhode Island was heavily involved in the slave trade during the post-revolution era. In 1774, the slave population of Rhode Island was 6.3%,[44] nearly twice as high as any other New England colony.

Rhode Island was also heavily involved in the Industrial Revolution, which began in America in 1787 when Thomas Somers reproduced textile machine plans which he imported from England. He helped to produce the Beverly Cotton Manufactory, in which Moses Brown of Providence took an interest. Moses Brown teamed up with Samuel Slater and helped to create the second cotton mill in America, a water-powered textile mill. The Industrial Revolution moved large numbers of workers into the cities, creating a permanently landless class who were therefore also voteless. By 1829, 60% of the state's free white males were ineligible to vote. Several attempts were unsuccessfully made to address this problem, and a new state constitution was passed in 1843 allowing landless men to vote if they could pay a $1 poll tax.

For the first several decades of statehood, Rhode Island was governed in accordance with the 1663 colonial charter. Voting rights were restricted to landowners holding at least $134 in property, disenfranchising well over half of the state's male citizens. The charter apportioned legislative seats equally among the state's towns, over-representing rural areas and under-representing the growing industrial centers. Additionally, the charter disallowed landless citizens from filing civil suits without endorsement from a landowner.[45] Bills were periodically introduced in the legislature to expand suffrage, but they were invariably defeated. In 1841, activists led by Thomas W. Dorr organized an extralegal convention to draft a state constitution,[46] arguing that the charter government violated the Guarantee Clause in Article Four, Section Four of the United States Constitution. In 1842, the charter government and Dorr's supporters held separate elections, and two rival governments claimed sovereignty over the state. Dorr's supporters led an armed rebellion against the charter government, and Dorr was arrested and imprisoned for treason against the state.[47] Later that year, the legislature drafted a state constitution, removing property requirements for American-born citizens but keeping them in place for immigrants, and retaining urban under-representation in the legislature.[48]

In the early 19th century, Rhode Island was subject to a tuberculosis outbreak which led to public hysteria about vampirism.

Civil War to Progressive Era: 1860–1929

During the American Civil War, Rhode Island was the first Union state to send troops in response to President Lincoln's request for help from the states. Rhode Island furnished 25,236 fighting men, of whom 1,685 died. On the home front, Rhode Island and the other northern states used their industrial capacity to supply the Union Army with the materials that it needed to win the war. The United States Naval Academy moved to Rhode Island temporarily during the war.

In 1866, Rhode Island abolished racial segregation in the public schools throughout the state.[49]

During World War I, Rhode Island furnished 28,817 soldiers, of whom 612 died. After the war, the state was hit hard by the Spanish Influenza.[50]

In the 1920s and 1930s, rural Rhode Island saw a surge in Ku Klux Klan membership, largely in reaction to large waves of immigrants moving to the state. The Klan is believed to be responsible for burning the Watchman Industrial School in Scituate, which was a school for African-American children.[51]

Growth in the modern era: 1929–present

Since the Great Depression, the Rhode Island Democratic Party has dominated local politics. Rhode Island has comprehensive health insurance for low-income children and a large social safety net. Many urban areas still have a high rate of children in poverty. Due to an influx of residents from Boston, increasing housing costs have resulted in more homeless in Rhode Island.[52]

The 350th Anniversary of the founding of Rhode Island was celebrated with a free concert held on the tarmac of the Quonset State Airport on August 31, 1986. Performers included Chuck Berry, Tommy James, and headliner Bob Hope.

In 2003, a nightclub fire in West Warwick claimed 100 lives and resulted in nearly twice as many injured, catching national attention. The fire resulted in criminal sentences.[53]

In March 2010, areas of the state received record flooding due to rising rivers from heavy rain. The first period of rainy weather in mid-March caused localized flooding and, two weeks later, more rain caused more widespread flooding in many towns, especially south of Providence. Rain totals on March 29–30, 2010 exceeded 14 inches (35.5 cm) in many locales, resulting in the inundation of area rivers—especially the Pawtuxet River which runs through central Rhode Island. The overflow of the Pawtuxet River, nearly 11 feet (3 m) above flood stage, submerged a sewage treatment plant and closed a five-mile (8 km) stretch of Interstate 95. In addition, it flooded two shopping malls, numerous businesses, and many homes in the towns of Warwick, West Warwick, Cranston, and Westerly. Amtrak service was also suspended between New York and Boston during this period. Following the flood, Rhode Island was in a state of emergency for two days. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was called in to help flood victims.

Government

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 39.80% 179,421 | 55.44% 249,902 |

| 2012 | 35.24% 157,204 | 62.70% 279,677 |

| 2008 | 35.21% 165,391 | 63.13% 296,571 |

| 2004 | 38.67% 169,046 | 59.42% 259,760 |

| 2000 | 31.91% 130,555 | 60.99% 249,508 |

| 1996 | 26.82% 104,683 | 59.71% 233,050 |

| 1992 | 29.02% 131,601 | 47.04% 213,299 |

| 1988 | 43.93% 177,761 | 55.64% 225,123 |

| 1984 | 51.66% 212,080 | 48.02% 197,106 |

| 1980 | 37.20% 154,793 | 47.70% 198,342 |

| 1976 | 44.10% 181,249 | 55.40% 227,636 |

| 1972 | 53.00% 220,383 | 46.80% 194,645 |

| 1968 | 31.80% 122,359 | 64.00% 246,518 |

| 1964 | 19.10% 74,615 | 80.90% 315,463 |

| 1960 | 36.40% 147,502 | 63.60% 258,032 |

| 1956 | 58.30% 225,819 | 41.70% 161,790 |

| 1952 | 50.90% 210,935 | 49.10% 203,293 |

The capital of Rhode Island is Providence. The state's current governor is Gina Raimondo (D), and the lieutenant governor is Daniel McKee (D). Raimondo became Rhode Island's first woman governor with a plurality of the vote in the November 2014 state elections.[54] Its United States Senators are Jack Reed (D) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D). Rhode Island's two United States Representatives are David Cicilline (D-1) and Jim Langevin (D-2). See congressional districts map.

Rhode Island is one of a few states that do not have an official Governor's residence. See List of Rhode Island Governors.

The state legislature is the Rhode Island General Assembly, consisting of the 75-member House of Representatives and the 38-member Senate. Both houses of the bicameral body are currently dominated by the Democratic Party; the presence of the Republican Party is almost non-existent in the state government, with Republicans holding a handful of seats in both the Senate and House of Representatives.

Elections

Rhode Island's population barely crosses the threshold for additional votes in both the federal House of Representatives and Electoral College; it is well represented relative to its population, with the eighth-highest number of electoral votes and second-highest number of House Representatives per resident. Based on its area, Rhode Island even has the highest density of electoral votes.[55]

Federally, Rhode Island is a reliably Democratic state during presidential elections, usually supporting the Democratic Presidential nominee. The state voted for the Republican Presidential candidate until 1908. Since then, it has voted for the Republican nominee for President seven times, and the Democratic nominee 17 times. The last 16 presidential elections in Rhode Island have resulted in the Democratic Party winning the Ocean State's Electoral College votes 12 times. In the 1980 presidential election, Rhode Island was one of six states to vote against Republican Ronald Reagan. No Republican since Reagan has even won any of the state's counties in a Presidential election. In 1988, Bush won over 40% of the state's popular vote, something that no Republican has done since.

Rhode Island was the Democrats' leading state in 1988 and 2000, and second-best in 1968, 1996, and 2004. Rhode Island's most one-sided Presidential election result was in 1964, with over 80% of Rhode Island's votes going for Lyndon B. Johnson. In 2004, Rhode Island gave John Kerry more than a 20-percentage-point margin of victory (the third-highest of any state), with 59.4% of its vote. All but three of Rhode Island's 39 cities and towns voted for the Democratic candidate. The exceptions were East Greenwich, West Greenwich, and Scituate.[56] In 2008, Rhode Island gave Barack Obama a 28-percentage-point margin of victory (the third-highest of any state), with 63% of its vote. All but one of Rhode Island's 39 cities and towns voted for the Democratic candidate (the exception being Scituate).[57]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of March 15, 2011[58][59] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Active voters | Inactive voters | Total voters | Percentage | |

| Democratic | 259,263 | 22,586 | 286,625 | 40.97% | |

| Republican | 65,033 | 6,792 | 72,613 | 10.38% | |

| Unaffiliated | 306,697 | 29,253 | 340,085 | 48.61% | |

| Total | 631,320 | 58,634 | 699,653 | 100% | |

Politics

Rhode Island has abolished capital punishment, making it one of 19 states that have done so. Rhode Island abolished the death penalty very early, just after Michigan, the first state to abolish it, and carried out its last execution in the 1840s. Rhode Island was the second to last state to make prostitution illegal. Until November 2009 Rhode Island law made prostitution legal provided it took place indoors.[60] In a 2009 study Rhode Island was listed as the 9th safest state in the country.[61]

In 2011, Rhode Island became the third state in the United States to pass legislation to allow the use of medical marijuana. Additionally, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed civil unions, and it was signed into law by Governor Lincoln Chafee on July 2, 2011. Rhode Island became the eighth state to fully recognize either same-sex marriage or civil unions.[62] Same-sex marriage became legal on May 2, 2013, and took effect August 1.[63]

Rhode Island has some of the highest taxes in the country, particularly its property taxes, ranking seventh in local and state taxes, and sixth in real estate taxes.[64]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 68,825 | — | |

| 1800 | 69,122 | 0.4% | |

| 1810 | 76,931 | 11.3% | |

| 1820 | 83,059 | 8.0% | |

| 1830 | 97,199 | 17.0% | |

| 1840 | 108,830 | 12.0% | |

| 1850 | 147,545 | 35.6% | |

| 1860 | 174,620 | 18.4% | |

| 1870 | 217,353 | 24.5% | |

| 1880 | 276,531 | 27.2% | |

| 1890 | 345,506 | 24.9% | |

| 1900 | 428,556 | 24.0% | |

| 1910 | 542,610 | 26.6% | |

| 1920 | 604,397 | 11.4% | |

| 1930 | 687,497 | 13.7% | |

| 1940 | 713,346 | 3.8% | |

| 1950 | 791,896 | 11.0% | |

| 1960 | 859,488 | 8.5% | |

| 1970 | 946,725 | 10.1% | |

| 1980 | 947,154 | 0.0% | |

| 1990 | 1,003,464 | 5.9% | |

| 2000 | 1,048,319 | 4.5% | |

| 2010 | 1,052,567 | 0.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 1,056,298 | 0.4% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[65] 2015 estimate[3] | |||

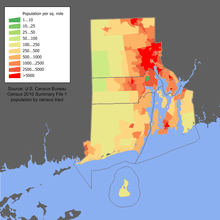

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Rhode Island was 1,056,298 on July 1, 2015, a 0.35% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[3] The center of population of Rhode Island is located in Providence County, in the city of Cranston.[66] A corridor of population can be seen from the Providence area, stretching northwest following the Blackstone River to Woonsocket, where 19th-century mills drove industry and development.

According to the 2010 Census, 81.4% of the population was White (76.4% non-Hispanic white), 5.7% was Black or African American, 0.6% American Indian and Alaska Native, 2.9% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 3.3% from two or more races. 12.4% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (they may be of any race).[67]

| Racial composition | 1970[68] | 1990[68] | 2000[69] | 2010[70] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 96.6% | 91.4% | 85.0% | 81.4% |

| Black | 2.7% | 3.9% | 4.5% | 5.7% |

| Asian | 0.4% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 2.9% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | – | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other race | 0.2% | 2.5% | 5.0% | 6.1% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 2.7% | 3.3% |

Of the people residing in Rhode Island, 58.7% were born in Rhode Island, 26.6% were born in a different state, 2.0% were born in Puerto Rico, U.S. Island areas or born abroad to American parent(s), and 12.6% were foreign born.[71]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2015, Rhode Island had an estimated population of 1,056,298, which is an increase of 1,125, or 0.10%, from the prior year and an increase of 3,731, or 0.35%, since the year 2010. This includes a natural increase since the last census of 15,220 people (that is 66,973 births minus 51,753 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 14,001 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 18,965 people, and migration within the country produced a net decrease of 4,964 people.

The ten largest ancestry groups in Rhode Island, according to the United States Census Bureau's 2014 American Community Survey,[72] are:

- 18.6%

Italian

Italian - 18.5%

Irish

Irish - 11.0%

English

English - 10.8%

French

French - 9.4%

Portuguese

Portuguese - 5.5%

German

German - 4.7%

French Canadian

French Canadian - 4.1%

Polish

Polish - 3.3%

American

American - 2.1%

Cape Verdean

Cape Verdean

Hispanics in the state make up 12.8% of the population, predominantly Dominican, Puerto Rican, and Guatemalan populations.[73]

According to the 2000 U.S. Census, 84% of the population aged 5 and older spoke only American English, while 8.07% spoke Spanish at home, 3.80% Portuguese, 1.96% French, 1.39% Italian and 0.78% speak other languages at home accordingly.[74]

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white, has declined from 96.1% in 1970 to 76.5% in 2011.[75][76] In 2011, 40.3% of Rhode Island's children under the age of one belonged to racial or ethnic minority groups, meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white.[77]

6.1% of Rhode Island's population were reported as under 5, 23.6% under 18, and 14.5% were 65 or older. Females made up approximately 52% of the population.

Rhode Island has a higher percentage of Americans of Portuguese ancestry, including Portuguese Americans and Cape Verdean Americans than any other state in the nation. Additionally, the state also has the highest percentage of Liberian immigrants, with more than 15,000 residing in the state.[78] Italian Americans make up a plurality in central and southern Providence County and French Canadians form a large part of northern Providence County. Irish Americans have a strong presence in Newport and Kent counties. Americans of English ancestry still have a presence in the state as well, especially in Washington County, and are often referred to as "Swamp Yankees." African immigrants, including Cape Verdean Americans, Liberian Americans, Nigerian Americans and Ghanaian Americans, form significant and growing communities in Rhode Island.

Although Rhode Island has the smallest land area of all 50 states, it has the second highest population density of any state in the Union, second to that of New Jersey.

Religion

A Pew survey of Rhode Island residents' religious self-identification showed the following distribution of affiliations: Roman Catholic 43%, Protestant 27%, Jewish 1%, Orthodox 1%, Jehovah's Witnesses 1%, Buddhism 1%, Mormonism 0.5%, Hinduism 0.5%, Islam 0.5% and Non-religious 23%.[79] The largest denominations are the Roman Catholic Church with 456,598 adherents, the Episcopal Church with 19,377, the American Baptist Churches USA with 15,220, and the United Methodist Church with 6,901 adherents.[80]

Rhode Island has one of the highest percentage of Roman Catholics[81] in the nation mainly due to large Irish, Italian, and French Canadian immigration in the past; recently, significant Portuguese and various Hispanic communities have also been established in the state. Though it has one of the highest overall Catholic percentages of any state, none of Rhode Island's individual counties ranks among the 10 most Catholic in the United States, as Catholics are very evenly spread throughout the state.

The Jewish community of Rhode Island is centered in the Providence area, and emerged during a wave of Jewish immigration predominately from Eastern Europeans shtetls between 1880 and 1920. The presence of the Touro Synagogue in Newport, the oldest existing synagogue in the United States, emphasizes that these second-wave immigrants did not create Rhode Island's first Jewish community; a comparatively smaller wave of Spanish and Portuguese Jews immigrated to Newport during the colonial era.

Cities and towns

Rhode Island is divided into five counties but it has no county governments, along with Connecticut and the rest of New England, to a partial extent. The entire state is divided into municipalities, which handle all local government affairs.

There are 39 cities and towns in Rhode Island. Major population centers today result from historical factors; development took place predominantly along the Blackstone, Seekonk, and Providence Rivers with the advent of the water-powered mill. Providence is the base of a large metropolitan area.

The state's 15 largest municipalities ranked by population are:

- Providence (178,042)[82]

- Warwick (82,672)[83]

- Cranston (80,387)[84]

- Pawtucket (71,148)[85]

- East Providence (47,034)[86]

- Woonsocket (40,186)[87]

- Coventry (36,014)[88]

- Cumberland (32,506)[88]

- North Providence (32,078)[88]

- South Kingstown (30,639)[88]

- West Warwick (29,191)[88]

- Johnston (28,768)[88]

- North Kingstown (26,486)[88]

- Newport (24,672)[89]

- Bristol (22,954)[88]

Some of Rhode Island's cities and towns are further partitioned into villages, in common with many other New England states. Notable villages include Kingston in the town of South Kingstown, which houses the University of Rhode Island; Wickford in the town of North Kingstown, the site of an annual international art festival; and Wakefield where the Town Hall is located for the Town of South Kingstown.[90]

- Major Cities of Rhode Island

1. Providence

1. Providence- 2. Warwick

3. Cranston

3. Cranston 4. Pawtucket

4. Pawtucket

- 6. Woonsocket

7. Coventry

7. Coventry 8. Cumberland

8. Cumberland

- 10. South Kingstown

11. West Warwick

11. West Warwick- 12. Johnston

13. North Kingstown

13. North Kingstown 14. Newport

14. Newport 15. Bristol

15. Bristol

Economy

The Rhode Island economy had a colonial base in fishing.

The Blackstone River Valley was a major contributor to the American Industrial Revolution. It was in Pawtucket that Samuel Slater set up Slater Mill in 1793,[91] using the waterpower of the Blackstone River to power his cotton mill. For a while, Rhode Island was one of the leaders in textiles. However, with the Great Depression, most textile factories relocated to southern US states. The textile industry still constitutes a part of the Rhode Island economy but does not have the same power that it once had.

Other important industries in Rhode Island's past included toolmaking, costume jewelry, and silverware. An interesting by-product of Rhode Island's industrial history is the number of abandoned factories, many of them now being used for condominiums, museums, offices, and low-income and elderly housing. Today, much of the economy of Rhode Island is based in services, particularly healthcare and education, and still manufacturing to some extent.[92][93] The state's nautical history continues in the 21st century in the form of nuclear submarine construction.

Per the 2013 American Communities Survey, Rhode Island has the highest paid elementary school teachers in the country, with an average salary of $75,028 (adjusted to inflation).[94]

The headquarters of Citizens Financial Group is located in Providence, the 14th largest bank in the United States.[95] The Fortune 500 companies CVS Caremark and Textron are based in Woonsocket and Providence, respectively. FM Global, GTECH Corporation, Hasbro, American Power Conversion, Nortek, and Amica Mutual Insurance are all Fortune 1000 companies that are based in Rhode Island.[96]

Rhode Island's 2000 total gross state production was $46.18 billion (adjusted to inflation), placing it 45th in the nation. Its 2000 per capita personal income was $41,484 (adjusted to inflation), 16th in the nation. Rhode Island has the lowest level of energy consumption per capita of any state.[97][98][99] Additionally, Rhode Island is rated as the 5th most energy efficient state in the country.[100][101] In December 2012, the state's unemployment rate was 10.2%.[102]

Health services are Rhode Island's largest industry. Second is tourism, supporting 39,000 jobs, with tourism-related sales at $4.56 billion (adjusted to inflation) in the year 2000. The third-largest industry is manufacturing.[103] Its industrial outputs are submarine construction, shipbuilding, costume jewelry, fabricated metal products, electrical equipment, machinery, and boatbuilding. Rhode Island's agricultural outputs are nursery stock, vegetables, dairy products, and eggs.

Rhode Island's taxes were appreciably higher than neighboring states,[64] because Rhode Island's income tax was based on 25% of the payer's federal income tax payment.[104] Former Governor Donald Carcieri claimed that the higher tax rate had an inhibitory effect on business growth in the state and called for reductions to increase the competitiveness of the state's business environment. In 2010, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a new state income tax structure that was then signed into law on June 9, 2010 by Governor Carcieri.[105] The income tax overhaul has now made Rhode Island competitive with other New England states by lowering its maximum tax rate to 5.99% and reducing the number of tax brackets to three.[106] The state's first income tax was enacted in 1971.[107]

Largest employers

As of March 2011, the largest employers in Rhode Island (excluding employees of municipalities) are the following:[108]

| Rank | Employer | Employees | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Rhode Island | 14,904 | Full-time equivalents |

| 2 | Lifespan Hospital Group | 11,869 | Rhode Island Hospital (7,024 employees), The Miriam Hospital (2,410), Newport Hospital (919), Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital (800), Lifespan Corporate Services (580), Newport Alliance Newport (68), Lifespan MSO (53), and Home Medical (15) |

| 3 | U.S. federal government | 11,581 | Excludes 3,000 active duty military personnel and 7,000 reservists, but includes 250 employees of the Naval War College. |

| 4 | Roman Catholic Diocese of Providence | 6,200 | |

| 5 | Care New England | 5,953 | Employees at: Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (3,134), Kent County Memorial Hospital (1,850), Butler Hospital (800), VNA of Care New England (140), and Care New England (29) |

| 6 | CVS Caremark | 5,800 | The corporate headquarters are at Woonsocket (5,630 employees). The corporation also has 170 employees at Pharmacare |

| 7 | Citizens Financial Group (subsidiary of The Royal Bank of Scotland Group) |

4,991 | |

| 8 | Brown University | 4,800 | Excludes student employees. |

| 9 | Stop & Shop Supermarket (subsidiary of Ahold) |

3,632 | |

| 10 | Bank of America | 3,500 | |

| 11 | Fidelity Investments | 2,934 | 2,434 employees in Smithfield and 500 in Providence |

| 12 | Rhode Island ARC | 2,851 | Employees at James L. Maher Center (700), The Homestead Group (650), Cranston Arc (374), The ARC of Blackstone Valley (350), Kent County ARC (500), The Fogarty Center (225), and Westerly Chariho, ARC (52) |

| 13 | MetLife Insurance Co. | 2,604 | |

| 14 | General Dynamics Corp. | 2,243 | 2,200 employees at General Dynamics Electric Boat in North Kingstown, and 43 employees at General Dynamics Information Technology – Newport in Middletown adjacent to the Naval Undersea Warfare Center[109] |

| 15 | University of Rhode Island | 2,155 | |

| 16 | Wal-Mart | 2,078 | |

| 17 | The Jan Companies | 2050 | Employees at Jan-Co Burger King (1,500) (Burger King franchiser); Newport Creamery, LLC (400), Quidnessett Country Club (100), and The Country Inn (50) |

| 18 | Shaw's Supermarkets (subsidiary of Albertsons LLC) |

1,900 | |

| 19 | St. Joseph Health Services and Hospitals of Rhode Island/CharterCARE Health Partners | 1,865 | Employees at Our Lady of Fatima Hospital (1,343) and St. Joseph Hospital for Specialty Care (522) |

| 20 | The Home Depot, Inc. | 1,780 |

Transportation

Bus

The Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) operates statewide intra- and intercity bus transport from its hubs at Kennedy Plaza in Providence, Pawtucket, and Newport. RIPTA bus routes serve 38 of Rhode Island's 39 cities and towns. (New Shoreham on Block Island is not served). RIPTA currently operates 58 routes, including daytime trolley service (using trolley-style replica buses) in Providence and Newport.

Ferry

From 2000 through 2008, RIPTA offered seasonal ferry service linking Providence and Newport (already connected by highway) funded by grant money from the United States Department of Transportation. Though the service was popular with residents and tourists, RIPTA was unable to continue on after the federal funding ended. Service was discontinued as of 2010.[110] The service was resumed in 2016 and has been successful. The privately run Block Island Ferry[111] links Block Island with Newport and Narragansett with traditional and fast-ferry service, while the Prudence Island Ferry[112] connects Bristol with Prudence Island. Private ferry services also link several Rhode Island communities with ports in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York. The Vineyard Fast Ferry[113] offers seasonal service to Martha's Vineyard from Quonset Point with bus and train connections to Providence, Boston, and New York. Viking Fleet[114] offers seasonal service from Block Island to New London, Connecticut, and Montauk, New York.

Rail

The MBTA Commuter Rail's Providence/Stoughton Line links Providence and T.F. Green Airport with Boston. The line was later extended southward to Wickford Junction, with service beginning April 23, 2012. The state hopes to extend the MBTA line to Kingston and Westerly. as well as explore the possibility of extending Connecticut's Shore Line East to T.F. Green Airport.[115] Amtrak's Acela Express stops at Providence Station (the only Acela stop in Rhode Island), linking Providence to other cities in the Northeast Corridor. Amtrak's Northeast Regional service makes stops at Providence Station, Kingston, and Westerly.

Aviation

Rhode Island's primary airport for passenger and cargo transport is T. F. Green Airport in Warwick, though most Rhode Islanders who wish to travel internationally on direct flights and those who seek a greater availability of flights and destinations often fly through Logan International Airport in Boston.

Limited access highways

Interstate 95 runs southwest to northeast across the state, linking Rhode Island with other states along the East Coast. Interstate 295 functions as a partial beltway encircling Providence to the west. Interstate 195 provides a limited-access highway connection from Providence (and Connecticut and New York via I-95) to Cape Cod. Initially built as the easternmost link in the (now cancelled) extension of Interstate 84 from Hartford, Connecticut, a portion of U.S. Route 6 through northern Rhode Island is limited-access and links I-295 with downtown Providence.

Several Rhode Island highways extend the state's limited-access highway network. RI-4 is a major north-south freeway linking Providence and Warwick (via I-95) with suburban and beach communities along Narragansett Bay. RI-10 is an urban connector linking downtown Providence with Cranston and Johnston. RI-37 is an important east-west freeway through Cranston and Warwick and links I-95 with I-295. RI-99 links Woonsocket with Providence (via RI-146). RI-146 travels through the Blackstone Valley, linking Providence and I-95 with Worcester, Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Turnpike. RI-403 links RI-4 with Quonset Point.

Several bridges cross Narragansett Bay connecting Aquidneck Island and Conanicut Island to the mainland, most notably the Claiborne Pell Newport Bridge and the Jamestown-Verrazano Bridge.

Bicycle paths

The East Bay Bike Path stretches from Providence to Bristol along the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay, while the Blackstone River Bikeway will eventually link Providence and Worcester. In 2011, Rhode Island completed work on a marked on-road bicycle path through Pawtucket and Providence, connecting the East Bay Bike Path with the Blackstone River Bikeway, completing a 33.5 miles (54 km) bicycle route through the eastern side of the state.[116] The William C. O'Neill Bike Path (commonly known as the South County Bike Path) is a 8-mile (13 km) path through South Kingstown and Narragansett. The 14-mile (22.5 km) Washington Secondary Bike Path stretches from Cranston to Coventry, and the 2-mile (3 km) Ten Mile River Greenway path runs through East Providence and Pawtucket.

Environmental issues

On May 29, 2014, Governor Lincoln D. Chafee announced that Rhode Island was one of eight states to release a collaborative Action Plan to put 3.3 million zero emission vehicles on the roads by 2025. The goal of the plan is to reduce greenhouse gas and smog-causing emissions. The Action Plan covers promoting zero emission vehicles and investing in the infrastructure to support them.[117]

In 2014, Rhode Island received grants from the Environmental Protection Agency in the amount of $2,711,685 to clean up Brownfield sites in eight locations. The intent of the grants was to provide communities with the funding necessary to assess, clean up, and redevelop contaminated properties, boost local economies, and leverage jobs while protecting public health and the environment.[118]

In 2013, the "Lots of Hope" program was established in the City of Providence to focus on increasing the city's green space and local food production, improve urban neighborhoods, promote healthy lifestyles and improve environmental sustainability. "Lots of Hope" supported by a $100,000 grant will partner with the City of Providence, the Soutside Community Land Trust and the Rhode Island Foundation to convert city-owned vacant lots into productive urban farms.[119]

In 2012, Rhode Island passed bill S2277/H7412, "An act relating to Health and Safety – Environmental Cleanup Objectives for Schools", informally known as the "School Siting Bill." The bill, sponsored by Senator Juan Pichardo and Representative Scott Slater and signed into law by the Governor, made Rhode Island the first state in the US to prohibit school construction on vapor intrusion Brownfield Sites where there is an ongoing potential for toxic vapors to negatively impact indoor air quality. It also creates a public participation process whenever a city or town considers building a school on any other kind of contaminated site.[120]

Media

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Colleges and universities

Rhode Island has several colleges and universities:

- Brown University

- Bryant University

- Community College of Rhode Island

- Johnson & Wales University

- Naval War College

- New England Institute of Technology

- Providence College

- Rhode Island College

- Rhode Island School of Design

- Roger Williams University

- Salve Regina University of Newport

- University of Rhode Island

Culture

Local accent

Some Rhode Islanders speak with the distinctive, non-rhotic, traditional Rhode Island accent that many compare to a cross between the New York City and Boston accents (e.g., "water" sounds like "watuh"). Many Rhode Islanders distinguish a strong aw sound [ɔə] (i.e., do not exhibit the cot–caught merger) as one might hear in New Jersey or New York City; for example, the word coffee is pronounced [ˈkʰɔəfi] KAW-fee.[121] This type of accent was brought to the region by early settlers from eastern England in the Puritan migration to New England in the mid-17th century.[122]

Rhode Islanders refer to a drinking fountain as a "bubbler" (sometimes pronounced "bubahluh") and sometimes call milkshakes "cabinets". A foot-long, overstuffed sandwich (of whatever kind) is called a "grinder."

Food and beverages

Several foods and dishes are unique to Rhode Island and some are hard to find outside of the state. Hot wieners are sometimes called gaggers, weinies, or New York System wieners, and they are smaller than a standard hot dog, served covered in a meat sauce, chopped onions, mustard, and celery salt. Famous to Rhode Island is Snail Salad, which is served at numerous restaurants throughout the state. The dish is normally prepared "family style" with over five pounds of snails mixed in with other ingredients commonly found in seafood dishes.[123] Grinders are submarine sandwiches, with a popular version being the Italian grinder, which is made with cold cuts (usually ham, prosciutto, capicola, salami, and Provolone cheese). Linguiça or chouriço (a spicy Portuguese sausage) and peppers is also popular among the state's large Portuguese community, eaten with hearty bread (though this is also popular in other areas of New England).

Pizza strips are prepared in Italian bakeries and sold in most supermarkets and convenience stores. They are rectangular strips of pizza without cheese. Their rich flavor comes solely from a dense, zesty tomato paste baked on a half-inch (1.3 cm) thick pan pizza crust, and may be enjoyed warm or cold. Party pizza is a box of these pizza strips. Spinach pies are similar to a calzone but filled with seasoned spinach instead of meat, sauce, and cheese. Variations can include black olives or pepperoni with the spinach.

As in colonial times, johnnycakes are made with corn meal and water, then pan-fried much like pancakes. During fairs and carnivals, Rhode Islanders enjoy dough boys, plate-sized disks of fried dough sprinkled with powdered sugar (or pizza sauce). Zeppoles are Italian doughnut-like pastries traditionally eaten on Saint Joseph's Day, often made with exposed centers of vanilla pudding, cream filling, or ricotta cream, and sometimes topped with a cherry.

As in many coastal states, seafood is readily available. Shellfish is extremely popular, with clams being used in multiple ways. The quahog is a large local clam usually used in a chowder. (The word quahog comes from the Narragansett Indian word "poquauhock"; see A Key into the Language of America by Roger Williams 1643.) It is also ground and mixed with stuffing (and sometimes spicy minced sausage) and then baked in its shell to form a stuffie. Steamed clams are also a very popular dish. Calamari (squid) is sliced into rings and fried and is served as an appetizer in most Italian restaurants, typically Sicilian-style (i.e., tossed with sliced banana peppers and with marinara sauce on the side).

Rhode Island, like the rest of New England, has a tradition of clam chowder. Both the white New England variety and the red Manhattan variety are popular, but there is also a unique clear-broth chowder known as Rhode Island Clam Chowder available in many restaurants. According to Good Eats, the addition of tomatoes in place of milk was initially the work of Portuguese immigrants in Rhode Island, as tomato-based stews were already a traditional part of Portuguese cuisine, and milk was costlier than tomatoes. Scornful New Englanders called this modified version "Manhattan-style" clam chowder because, in their view, calling someone a New Yorker was an insult.

A culinary tradition in Rhode Island is the clam cake (also known as a clam fritter outside of Rhode Island), a deep fried ball of buttery dough with chopped bits of clam inside. They are sold by the half-dozen or dozen in most seafood restaurants around the state. The quintessential summer meal in Rhode Island is chowder and clam cakes.

Clams Casino originated in Rhode Island after being invented by Julius Keller, the maitre d' in the original Casino next to the seaside Towers in Narragansett.[124] Clams Casino resemble the beloved stuffed quahog but are generally made with the smaller littleneck or cherrystone clam and are unique in their use of bacon as a topping.

According to a Providence Journal article, the state features both the highest number and highest density of coffee/doughnut shops per capita in the country, with 342 coffee/doughnut shops in the state. At one point, Dunkin' Donuts alone had over 225 locations;[125] as of December 2013, there are still more than 175 Dunkin' Donuts shops within the state.[126]

The official state drink of Rhode Island is coffee milk,[127] a beverage created by mixing milk with coffee syrup. This unique syrup was invented in the state and is sold in almost all Rhode Island supermarkets, as well as border states. Coffee milk contains some caffeine, yet it is sold in school cafeterias throughout the state. Strawberry milk is also as popular as chocolate milk.

Famous Rhode Islanders

| Rhode Island state symbols | |

|---|---|

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Rhode Island Red Chicken |

| Fish | Striper Bass |

| Flower | Violet |

| Tree | Red maple |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Coffee milk |

| Food | Rhode Island Greening Apple |

| Mineral | Bowenite |

| Rock | Cumberlandite |

| Shell | Northern Quahog |

| Slogan | Unwind, "Hope" |

| Soil | Narragansett |

| Song |

Rhode Island, Rhode Island, It's for Me |

| Tartan | Rhode Island Tartan |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

|

Released in 2001 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Low numbered license plates

Politicians have distributed low-numbered license plates since 1904 (when the first black and white porcelain license plates were issued by the state) as a way to reward supporters or associates; such plates have become a status symbol, similar to the culture surrounding low-numbered plates in Delaware.[128] State officials made Rhode Island one of the few states to allow the owner to transfer license plate(s) to other family members in their will.[129] Additionally, an official license plate lottery was implemented in 1995 through the Governor's Office[130] for "preferred plates".[131] A plate's value depends on its category, with the traditional "Ocean State" legend plate (or "wave plate") being the most valuable. The main branch of the Division of Motor Vehicles was also cooperative in allowing a prospective tag-holder to choose the two letters at the beginning of the plate serial, provided that such a combination was available on-hand and was not considered a "preferred plate".

Popular culture

The Farrelly brothers and Seth MacFarlane depict Rhode Island in popular culture, often making comedic parodies of the state. MacFarlane's television series Family Guy is based in a fictional Rhode Island city named Quahog, and notable local events and celebrities are regularly lampooned. Peter is seen working at the Pawtucket brewery, and other state locations are mentioned.

The movie High Society (starring Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly, and Frank Sinatra) was set in Newport, Rhode Island.

The film adaptation of The Great Gatsby from 1974 was also filmed in Newport.

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis and John F. Kennedy were married at St. Mary's church in Newport, Rhode Island. Their reception was held at Hammersmith Farm, the Bouvier summer home in Newport.

Cartoonist Don Bousquet, a state icon, has made a career out of Rhode Island culture, drawing Rhode Island-themed gags in The Providence Journal and Yankee magazine. These cartoons have been reprinted in the Quahog series of paperbacks (I Brake for Quahogs, Beware of the Quahog, and The Quahog Walks Among Us.) Bousquet has also collaborated with humorist and Providence Journal columnist Mark Patinkin on two books: The Rhode Island Dictionary and The Rhode Island Handbook.

The 1998 film Meet Joe Black was filmed at Aldrich Mansion in the Warwick Neck area of Warwick.

Body of Proof's first season was filmed entirely in Rhode Island.[132] The show premiered on March 29, 2011.[133]

The 2007 Steve Carell and Dane Cook film Dan in Real Life was filmed in various coastal towns in the state. The sunset scene with the entire family on the beach takes place at Napatree Point.

Jersey Shore star Pauly D filmed part of his spin-off The Pauly D Project in his hometown of Johnston.

The Comedy Central cable television series Another Period is set in Newport during the Gilded Age.

Famous firsts in Rhode Island

Rhode Island has been the first in a number of initiatives. As a colony, the state enacted the first law prohibiting slavery in North America on May 18, 1652.[134]

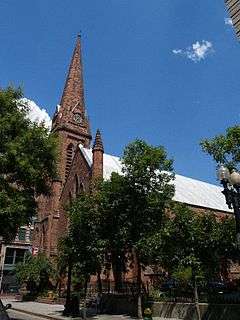

Slater Mill in Pawtucket was the first commercially successful cotton-spinning mill with a fully mechanized power system in America and was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in the US.[135] The oldest Fourth of July Parade in the country is still held annually in Bristol, Rhode Island. The first Baptist Church in America was founded in Providence in 1638.[136] Ann Smith Franklin of the Newport Mercury was the first female newspaper editor in America (August 22, 1762). She was the editor of "The Newport Mercury" in Newport, Rhode Island.[134] Touro Synagogue was the first synagogue in America, founded in Newport in 1763.[134]

The first act of armed rebellion in America against the British Crown was the boarding and burning of the Revenue Schooner Gaspee in Narragansett Bay on June 10, 1772. The idea of a Continental Congress was first proposed at a town meeting in Providence on May 17, 1774. Rhode Island elected the first delegates (Stephen Hopkins and Samuel Ward) to the Continental Congress on June 15, 1774. The Rhode Island General Assembly created the first standing army in the colonies (1,500 men) on April 22, 1775. On June 15, 1775, the first naval engagement of the American Revolution occurred between a Colonial Sloop commanded by Capt. Abraham Whipple and an armed tender of the British Frigate Rose. The tender was chased aground and captured. Later in June, the General Assembly created the first American Navy when it commissioned the Sloops Katy and Washington, armed with 24 guns and commanded by Abraham Whipple, who was promoted to Commodore. Rhode Island was the first Colony to declare independence from Britain on May 4, 1776.[134]

Pelham Street in Newport was the first in America to be illuminated by gaslight in 1806.[134] The first strike in the United States in which women participated occurred in Pawtucket in 1824.[134] Watch Hill has the nation's oldest carousel that has been in continuous operation since 1850.[134] The motion picture machine (a machine showing animated pictures) was patented in Providence on April 23, 1867.[134] The first lunch wagon in America was introduced in Providence in 1872.[134] The first nine-hole golf course in America was completed in Newport in 1890.[134] The first state health laboratory was established in Providence on September 1, 1894.[134] The Rhode Island State House was the first building with an all-marble dome to be built in the United States (1895–1901).[134] The first automobile race on a track was held in Cranston on September 7, 1896.[134] The first automobile parade was held in Newport on September 7, 1899, on the grounds of Belcourt Castle.[134]

The first NFL night game was held on November 6, 1929, at Providence's Kinsley Park. The Chicago (now Arizona) Cardinals defeated the Providence Steam Roller 16–0.

In 1980, Rhode Island became the first state to decriminalize prostitution indoors, but indoor prostitution was outlawed again in 2009; see Prostitution in Rhode Island.

Miscellaneous local culture

Rhode Island is nicknamed "The Ocean State", and the nautical nature of Rhode Island's geography pervades its culture. Newport Harbor, in particular, holds many pleasure boats. In the lobby of T. F. Green, the state's main airport, is a large life-sized sailboat,[137] and the state's license plates depict an ocean wave or a sailboat.[138]

Additionally, the large number of beaches in Washington County lures many Rhode Islanders south for summer vacation.[139]

The state was notorious for organized crime activity from the 1950s into the 1990s when the Patriarca crime family held sway over most of New England from its Providence headquarters.

Rhode Islanders developed a unique style of architecture in the 17th century called the stone-ender.[140]

Rhode Island is the only state to still celebrate Victory over Japan Day. It is known locally as "VJ Day" or simply "Victory Day".[141]

Sports

Professional

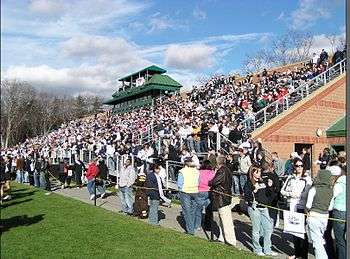

Rhode Island has two professional sports teams, both of which are top-level minor league affiliates for teams in Boston. The Pawtucket Red Sox baseball team of the Triple-A International League are an affiliate of the Boston Red Sox. They play at McCoy Stadium in Pawtucket and have won four league titles, the Governors' Cup, in 1973, 1984, 2012, and 2014. McCoy Stadium also has the distinction of being home to the longest professional baseball game ever played – 33 innings.

The other professional minor league team is the Providence Bruins ice hockey team of the American Hockey League, who are an affiliate of the Boston Bruins. They play in the Dunkin' Donuts Center in Providence and won the AHL's Calder Cup during the 1998–99 AHL season.

The Providence Reds were a hockey team that played in the Canadian-American Hockey League (CAHL) between 1926 and 1936 and the American Hockey League (AHL) from 1936 to 1977, the last season of which they played as the Rhode Island Reds. The team won the Calder Cup in 1938, 1940, 1949, and 1956. The Reds played at the Rhode Island Auditorium, located on North Main Street in Providence, Rhode Island from 1926 through 1972, when the team affiliated with the New York Rangers and moved into the newly built Providence Civic Center. The team name came from the rooster known as the Rhode Island Red. They moved to New York in 1977 and, after multiple name changes, are now called the Hartford Wolf Pack.

The Reds are the oldest continuously operating minor-league hockey franchise in North America, having fielded a team in one form or another since 1926 in the CAHL. It is also the only AHL franchise to have never missed a season. The AHL returned to Providence in 1992 in the form of the Providence Bruins.

Before the great expansion of athletic teams all over the country, Providence and Rhode Island in general played a great role in supporting teams. The Providence Grays won the first World Championship in baseball history in 1884. The team played their home games at the old Messer Street Field in Providence. The Grays played in the National League from 1878 to 1885. They defeated the New York Metropolitans of the American Association in a best of five game series at the Polo Grounds in New York. Providence won three straight games to become the first champions in major league baseball history. Babe Ruth played for the minor league Providence Grays of 1914 and hit his only official minor league home run for that team before being recalled by the Grays' parent club, the Boston Red Stockings.

The now-defunct professional football team the Providence Steam Roller won the 1928 NFL title. They played in a 10,000 person stadium called the Cycledrome.[142] The Providence Steamrollers played in the Basketball Association of America which became the National Basketball Association.

Rhode Island is also home to a top semi-professional soccer club, the Rhode Island Reds, which compete in the National premier soccer league, in the fourth division of U.S. Soccer.

Rhode Island is home to one top level non-minor league team, the Rhode Island Rebellion rugby league team, a semi-professional rugby league team that competes in the USA Rugby League, the Top Competition in the United States for the Sport of Rugby League.[143][144] The Rebellion play their home games at Classical High School in Providence.[145]

Collegiate and non-professional

There are four NCAA Division I schools in Rhode Island. All four schools compete in different conferences. The Brown University Bears compete in the Ivy League, the Bryant University Bulldogs compete in the Northeast Conference, the Providence College Friars compete in the Big East Conference, and the University of Rhode Island Rams compete in the Atlantic-10 Conference. Three of the schools' football teams compete in the Football Championship Subdivision, the second-highest level of college football in the United States. Brown plays FCS football in the Ivy League, Bryant plays FCS football in the Northeast Conference, and Rhode Island plays FCS football in the Colonial Athletic Association. All four of the Division I schools in the state compete in an intrastate all-sports competition known as the Ocean State Cup, with Bryant winning the most recent cup in 2011–12 academic year.

From 1930 to 1983, America's Cup races were sailed off Newport, and the extreme-sport X Games and Gravity Games were founded and hosted in the state's capital city.

The International Tennis Hall of Fame is in Newport at the Newport Casino, site of the first U.S. National Championships in 1881. The Hall of Fame and Museum were established in 1954 by James Van Alen as "a shrine to the ideals of the game".

Rhode Island is also home to the headquarters of the governing body for youth rugby league in the United States, the American Youth Rugby League Association or AYRLA. The AYRLA has started the first-ever Rugby League youth competition in Providence Middle Schools, a program at the RI Training School, in addition to starting the first High School Competition in the USA in Providence Public High School.[146]

Landmarks

The state capitol building is made of white Georgian marble. On top is the world's fourth largest self-supported marble dome.[147] It houses the Rhode Island Charter granted by King Charles II in 1663, the Brown University charter, and other state treasures.

The First Baptist Church of Providence is the oldest Baptist church in the Americas, founded by Roger Williams in 1638.

The first fully automated post office in the country is located in Providence. There are many historic mansions in the seaside city of Newport, including The Breakers, Marble House, and Belcourt Castle. Also located there is the Touro Synagogue, dedicated on December 2, 1763, considered by locals to be the first synagogue within the United States (see below for information on New York City's claim), and still serving. The synagogue showcases the religious freedoms that were established by Roger Williams, as well as impressive architecture in a mix of the classic colonial and Sephardic style. The Newport Casino is a National Historic Landmark building complex that presently houses the International Tennis Hall of Fame and features an active grass-court tennis club.

Scenic Route 1A (known locally as Ocean Road) is in Narragansett. "The Towers" is also located in Narragansett featuring a large stone arch. It was once the entrance to a famous Narragansett casino that burned down in 1900. The Towers now serve as an event venue and host the local Chamber of Commerce, which operates a tourist information center. Rhode Island also has three of the nation's tallest bridges.

The Newport Tower has been hypothesized to be of Viking origin, although most experts believe that it was a Colonial-era windmill.[148]

Notable people

See also

Rhode Island – Wikipedia book

Rhode Island – Wikipedia book

References

- ↑ "Rhode Island Government: Government". RI.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Office of the Secretary of State: A. Ralph Mollis: State Library. Sos.ri.gov. Retrieved on July 12, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015" (CSV). U.S. Census Bureau. December 26, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- 1 2 "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ↑ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach, James Hartmann and Jane Setter, eds., English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ↑ "Rhode Island". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ "Constitution of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations". State of Rhode Island General Assembly. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ↑ Office of the Secretary of State: Nellie M. Gorbea:

- ↑ "The May 4, 1776, Act of Renunciation". State of Rhode Island. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Jensen, Merrill (1959). The Articles of Confederation: An Interpretation of the Social-Constitutional History of the American Revolution, 1774–1781. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. xi, 184. ISBN 978-0-299-00204-6.

- ↑ "Letter from Certain Citizens of Rhode Island to the Federal Convention". Ashland, Ohio: TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ Flexner, James Thomas (1984). Washington, The Indispensable Man. New York: Signet. p. 208. ISBN 0-451-12890-7.

- ↑ Vile, John R. (2005). The Constitutional Convention of 1787: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of America's Founding (Volume 1: A-M). ABC-CLIO. p. 658. ISBN 1-85109-669-8. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ↑ "US constitution Ratification: RI". Usconstitution.net. January 8, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Colony Of Rhode Island A Brief History". celebrateboston.com. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Rhode Island Geography Maps". Dlt.ri.gov. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Verrazano, Giovanni. Verrazano's voyage along the Atlantic coast of North America, 1524. State University of New York at Albany. p. 10. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ↑ Giovanni da Verrazzano named a place on Rhode Island Puntum Iovianum in honor of his friend Paolo Giovio (Jovium in Latin) (1483–1542), humanist and historian. Giovio owned the Codex Cellere of Giovanni da Verrazzano containing the text of his first trip.

- ↑ "deLaet". S4U Languages – Brazilian translation. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ Elisha Potter, 1835. The Early History of Narragansett. Collections of the Rhode-Island Historical Society, v3. books.google.com

- ↑ books.google.com Samuel G. Arnold, History of Rhode Island (1859)

- ↑ Office of the Secretary of State: A. Ralph Mollis: State Library. Sos.ri.gov. Retrieved on April 12, 2014.

- ↑ Hamilton B. Staples, "Origins of the Names of the State of the Union", Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, vol. 68 (1882): Google Docs, Origins of the Names of the State of the Union

- ↑ Wootton, Anne (October 17, 2006). "In colonial Rhode Island, slavery played pivotal role". Brown Daily Herald.

- ↑ "Unfollowed abolishment of slavery in 1652 twist to Rhody's past". Warwick Beacon. November 18, 2010.

- ↑ Macris, Gina (November 3, 2010). "Strong 'no' to changing R.I. name". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ↑ Official Government Web Portal for the State of Rhode Island www.ri.gov/facts/history.php accessed May 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey. April 29, 2005. Archived from the original on November 2, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ↑ Olson, D. M, E. Dinerstein; et al. (2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11): 933–938. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ US Geological Survey topographical map Providence 1:250,000 (NK 19-7) 1958

- ↑ US Geological Survey topographical map Block Island (1:100,000) 30 x 60 minute series 1984 (41071-A1-TM-100)

- ↑ Recorded Highest Temperatures by State Information Please Almanac

- ↑ Recorded Lowest Temperatures by State Information Please Almanac

- ↑ "Average Temperature Range". Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- 1 2 An Album of Rhode Island History by Patrick T. Conley

- ↑ "Charter of Rhode Island (1663)". Lonang.com. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ King Philip's War Archived June 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "King Philip's War". Military History Online. July 17, 2004. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ "The Unrighteous Traffick". The Providence Journal. March 12, 2006. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ gaspee.org. "Gaspee Affair Archive". Gaspee Virtual Archives. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Know Rhode Island, RI Secretary of State". Sos.ri.gov. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Rhode Island Ratification of the U.S. Constitution". Usconstitution.net. January 8, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ The General Assembly of the Governor and Company of the English Colony of the Rhode Island (June 14, 1774). The Rhode Island Census of 1774 (Report). Hon. General Assembly. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ↑ Bolles, John Augustus (1842). The Affairs of Rhode Island, Being a Review of President Wayland's Discourse, a Vindication of the Sovereignty of the People, and a Refutation of the Doctrines and Doctors of Despotism. Boston: B.T. Albro. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ↑ Webster, Daniel (1848). The Rhode Island Question: Mr. Webster's Argument in the Supreme Court of the United States in the Case of Martin Luther vs. Luther M. Borden and Others, January 27th, 1848. Washington, D.C.: J. and G.S. Gideon. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ↑ Pitman, Joseph S. (1844). Report on the Trial of Thomas Wilson Dorr, for Treason Against the State of Rhode Island, Containing the Arguments of Counsel, and the Charge of Chief Justice Durfee. Boston: Tappan & Dennet. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ↑ King, Dan (1859). The Life and Times of Thomas Wilson Dorr, with Outlines of the Political History of Rhode Island. Boston: Dan King. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Rhode Island History: CHAPTER V: Change, Controversy, and War, 1846–1865". Archived from the original on February 3, 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2006.

- ↑ "Rhode Island History: CHAPTER VII: Boom, Bust, and War, 1900–1945". Archived from the original on March 2, 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2006.

- ↑ Robert Smith, In the 1920s the Klan Ruled the Countryside, The Rhode Island Century, The Providence Journal, April 26, 1999. Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Providence Neighborhood Profiles".

- ↑ Butler, Brian (February 21, 2003). "Nightclub Fire Kills 39 People". CNN.

- ↑ "Democrat Gina Raimondo becomes Rhode Island's first female governor". Reuters. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ↑ "New Jersey Presidential Election Voting History". 270towin.com. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Stewart, Charles. "nationwide2004". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved August 28, 2007. taken from web.mit.edu

- ↑ "CNN Election Results by town in Rhode Island". Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics" (PDF). RI Secretary of State. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Number of Solidly Democratic States Cut in Half From '08 to '10". Gallup.com. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Eric Tucker. "Rhode Island police seek stricter anti-prostitution laws". Union-Tribune Publishing Co. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Safest States". Walletpop.com. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ "RI Gov. Chafee signs bill allowing civil unions". WHDH-TV 7NEWS WHDH.COM. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ Archived May 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Downing, Neil. "Rhode Island taxes rising, now seventh in the country". Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ↑ Resident Population Data. "Resident Population Data – 2010 Census". 2010.census.gov. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ↑ "Population and Population Centers by State: 2000". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Rhode Island QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- 1 2 "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States". Census.gov. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ Population of Rhode Island: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts

- ↑ 2010 Census Data. "2010 Census Data". Census.gov. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder – Results". census.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ↑ "People Reporting Ancestry 2010-2014 American Community Survery 5-Year Estimates". American Fact Finder. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- ↑ "2010 Census quick facts: Rhode Island". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Language Map Data Center". Mla.org. July 17, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Rhode Island QuickFacts". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Rhode Island – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1790 to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ Exner, Rich (June 3, 2012). "Americans under age 1 now mostly minorities, but not in Ohio: Statistical Snapshot". The Plain Dealer.

- ↑ "Obama grants 12-month extension to Liberians on DED". The Providence Journal c/o The African Media Network. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ↑ "U.S. Religion Map and Religious Populations – U.S. Religious Landscape Study – Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life". Religions.pewforum.org. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | State Membership Report". www.thearda.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ↑ "The Largest Roman Catholic Communities". Adherents.com. 2000. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Providence city US census data". Quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved January 26, 2013.