Storer College

|

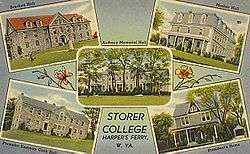

Storer College postcard (1910) | |

Former names | Storer Normal School |

|---|---|

| Active | 1865–1955 |

| Location |

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, United States 39°19′25.64″N 77°44′7.49″W / 39.3237889°N 77.7354139°WCoordinates: 39°19′25.64″N 77°44′7.49″W / 39.3237889°N 77.7354139°W |

Storer College was a historically black college located in Harpers Ferry in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It operated from 1865 until 1955. Its former campus is now part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

History

Storer School

For over 88 years, the place of education ultimately known as "Storer College" stood high above Harpers Ferry on Camp Hill. Beginning life as a one-room school for freedmen, Storer grew into a full-fledged degree-granting college open to all races, creeds, and colors, and men and women. Former slaves thrown into the world with no training, no skills, and no education found at Storer a place to learn to read and write, to teach others in their community, and to develop marketable skills. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren found place of learning in the days of racial segregation. Students left Storer with the education, the training, and perhaps most importantly, the sense of worth needed to make their way in an unsympathetic society.

Educating freedmen

The first building on Camp Hill, a portion of Harpers Ferry, Virginia, to open its doors to students was the Lockwood House, formerly the US Armory Paymaster's quarters. In 1865, as a representative of New England's Freewill Baptist Home Mission Society, Reverend Nathan Cook Brackett established a primary school in the war torn building, teaching reading, writing, and arithmetic to the children of former slaves.[1][2] This school was part of a larger national effort by northern philanthropic organizations and the government's Freedmen's Bureau to educate the thousands of African Americans freed by the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution. From Harpers Ferry, Reverend Brackett directed the efforts of dedicated missionary teachers, who provided a basic education to thousands of former slaves congregated in the relatively safe haven of the Shenandoah Valley by the end of the American Civil War.

Teaching teachers

Dedicated as they were, these few teachers could not begin to meet the educational needs of the freedmen in the area. By 1867, there were still only 16 teachers to educate 2,500 students. Reverend Brackett realized the only way to reach all these students was to train African American teachers. The little grammar school in the Lockwood House needed to become a teaching college.

In 1867, Reverend Brackett's school came to the attention of John Storer, a philanthropist from Maine through Rev. Oren B. Cheney, founder of Bates College, a Freewill Baptist school in Maine. Storer offered a $10,000 grant to the Freewill Baptists for a "colored school" in the South if several conditions could be met. First, the school must eventually become a degree-granting college. Second, the school had to be open to all applicants, regardless of race or gender. And, finally, the most difficult prerequisite: The Freewill Baptist Church had to match the $10,000 donation within the year. After a year-long effort, the money was raised, and Storer Normal School opened its doors, and by March 1868 it received its state charter.

Local attitudes

Raising $10,000 turned out to be easy compared to facing local resistance to a "colored school." Residents of Harpers Ferry tried everything from slander and vandalism to pulling political strings in their efforts to shut down the school. One teacher wrote, "it is unusual for me to go to the Post Office without being hooted at, and twice I have been stoned on the streets at noonday."

These efforts did not succeed in closing Storer Normal School, and eventually, local attitudes changed. Later in his life, Reverend Brackett became a respected citizen of Harpers Ferry.

The three Rs and more

Understanding that former slaves needed to learn more than the three Rs to function in society, Storer founders looked to provide more than a basic education. According to the first college catalog, students were to "receive counsel and sympathy, learn what constitutes correct living, and become qualified for the performance of the great work of life." In its early years, Storer taught freedmen to read, write, spell, do sums, and to go back into their communities to teach others these lessons.

As the years went by, Storer remained primarily a Teachers College, but added courses in higher education as well as in industrial training. Students graduated with a normal degree for teaching or an academic degree for those going on to college.

Civil rights

In 1881, Frederick Douglass delivered his famous speech on abolitionist John Brown at Storer Normal School.

In August 1906, Storer Normal School hosted the second conference of the Niagara Movement. Formed by a group of leading African American intellectuals, the Niagara Movement struggled to eliminate discrimination based on color. The movement's leader, Doctor W. E. B. Du Bois, rejected the prevalent theory of "accommodation" espoused by Booker T. Washington, who advocated conciliation rather than agitation as a means of gaining social equality. The Niagara Movement never hesitated to agitate, publishing an annual "Address to the World", demanding voting rights, educational and economic opportunities, justice in the courts, and recognitions in unions and the military. Their aggressive tone alienated many conservative African American and white leaders, and eroded political support for their group. During the 1906 conference, Storer staff expressed discomfort with the group's militancy and dismay at their tendency to consider even progressive whites as the enemy.

By 1910, five years after it was formed, the Niagara Movement was dissolved. While it did not produce material gains in the civil rights arena, the Niagara Movement made it clear there was a large group of people who would settle for nothing less than full civil rights, thereby laying a valuable foundation for the development of a more broad-based push for equality.

When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in New York City in 1910, many of the members of the failing Niagara Movement joined immediately. The NAACP adopted many of the goals of the Niagara Movement. In its most famous victory, the NAACP took Brown v. Board of Education to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954 and won. In an ironic twist of fate, Storer College, which had played host to the Niagara Movement that paved the way for the formation of the NAACP, suffered from that decision.

Storer College

In 1938, under the leadership of school president Henry T. McDonald, Storer became a college. Enrollment peaked at around 400, and dipped lower during World War II.

Although the school granted four-year degrees, it was never accredited, and the college was forced to turn away some students. Those who wanted to be doctors, for example, were not admitted, because the college lacked the money to provide the necessary facilities to properly prepare students for these advanced studies.

Final days

In 1954, the US Supreme Court decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case ended legal segregation in public schools in the United States. Immediately after the ruling, West Virginia withdrew its financial support from Storer College. Financial burdens had been accumulating for a decade, and in June 1955, Storer College closed its doors forever. (West Virginia continues to support two other historically black state universities: Bluefield State College and West Virginia State University.)

The legacy

In 1964, the movable physical assets of the college were transferred to the historically white Alderson-Broaddus College, a Baptist college, and used to establish scholarships for black students. The college's endowment was transferred to Virginia Union University, a historically black institution. Records of the college are maintained by Virginia Union, by Howard University and by West Virginia University's West Virginia and Regional History Center.

Virginia Union University considers graduates of the college to be alumni of VUU. VUU's L. Douglas Wilder Library and Learning Resource Center also holds Storer College's former library collection as well as some of the college's records.[3] Other Storer College records can be found at the library of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and at Howard University’s Moorland-Springarn Research Center.

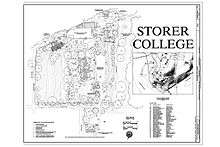

The campus of the college is now maintained as a part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. The three remaining structures that were used as part of the Storer College campus now house the National Park Service's Stephen T. Mather Training Center and the Service's library. The Training Center is one of four major training centers operated by and for the National Park Service, and is named for the Service's first Director, Stephen Mather.

Each August, the alumni of Storer College gather in Harpers Ferry for their now-annual reunion. At last count fewer than 70 remain; the last person to graduate in 1955 is now around 74.

Notable alumni and faculty

| Name | Class year | Notability | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Don Redman | arranger for the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra during the 1920s and 1930s. He also played saxophone and clarinet in the group. | ||

| William A. Saunders | African American professor | ||

| John Dunjee | Prominent Free Will Baptist preacher and early fundraiser for Storer | ||

| J. R. Clifford | 1875 | first African-American attorney from WV | |

| Hamilton Hatter | 1878 | African American professor | |

| Richard I. McKinney | first African-American president of Storer College | ||

| Nnamdi Azikiwe | 1926 | First President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria | |

| Mary J. Harris | Current Storer College Alumni President | ||

| John Francis Wheaton | 1882 | First African American member of the Minnesota State Legislature[4] |

References

- ↑ "Harpers Ferry National Historical Park - Storer College (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ↑ "Storer College".

- ↑ "Virginia Union University | Records of Storer College". www.vuu.edu. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ↑ An Ebony Legislator, St. Paul Daily Globe, February 12, 1899, accessed December 15, 2010.

External links

- Storer College Digital Collection at West Virginia and Regional History Center https://storercollege.lib.wvu.edu/

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. WV-277, "Storer College, Harpers Ferry, Jefferson County, WV"

- HABS No. WV-277-A, "Storer College, Anthony Hall"

- HABS No. WV-277-B, "Storer College, Mosher Hall"

- HABS No. WV-277-C, "Storer College, Lewis Anthony Library"

- HABS No. WV-277-D, "Storer College, Brackett Hall"

- HABS No. WV-277-E, "Storer College, Cook Hall, 252 McDowell Street"