Stress–strain analysis

Stress–strain analysis (or stress analysis) is an engineering discipline that uses many methods to determine the stresses and strains in materials and structures subjected to forces. In continuum mechanics, stress is a physical quantity that expresses the internal forces that neighboring particles of a continuous material exert on each other, while strain is the measure of the deformation of the material.

Stress analysis is a primary task for civil, mechanical and aerospace engineers involved in the design of structures of all sizes, such as tunnels, bridges and dams, aircraft and rocket bodies, mechanical parts, and even plastic cutlery and staples. Stress analysis is also used in the maintenance of such structures, and to investigate the causes of structural failures.

Typically, the starting point for stress analysis are a geometrical description of the structure, the properties of the materials used for its parts, how the parts are joined, and the maximum or typical forces that are expected to be applied to the structure. The output data is typically a quantitative description of how the applied forces spread throughout the structure, resulting in stresses, strains and the deflections of the entire structure and each component of that structure. The analysis may consider forces that vary with time, such as engine vibrations or the load of moving vehicles. In that case, the stresses and deformations will also be functions of time and space.

In engineering, stress analysis is often a tool rather than a goal in itself; the ultimate goal being the design of structures and artifacts that can withstand a specified load, using the minimum amount of material or that satisfies some other optimality criterion.

Stress analysis may be performed through classical mathematical techniques, analytic mathematical modelling or computational simulation, experimental testing, or a combination of methods.

The term stress analysis is used throughout this article for the sake of brevity, but it should be understood that the strains, and deflections of structures are of equal importance and in fact, an analysis of a structure may begin with the calculation of deflections or strains and end with calculation of the stresses.

Scope

General principles

Stress analysis is specifically concerned with solid objects. The study of stresses in liquids and gases is the subject of fluid mechanics.

Stress analysis adopts the macroscopic view of materials characteristic of continuum mechanics, namely that all properties of materials are homogeneous at small enough scales. Thus, even the smallest particle considered in stress analysis still contains an enormous number of atoms, and its properties are averages of the properties of those atoms.

In stress analysis one normally disregards the physical causes of forces or the precise nature of the materials. Instead, one assumes that the stresses are related to strain of the material by known constitutive equations.[1]

By Newton's laws of motion, any external forces that act on a system must be balanced by internal reaction forces,[2] or cause the particles in the affected part to accelerate. In a solid object, all particles must move substantially in concert in order to maintain the object's overall shape. It follows that any force applied to one part of a solid object must give rise to internal reaction forces that propagate from particle to particle throughout an extended part of the system. With very rare exceptions (such as ferromagnetic materials or planet-scale bodies), internal forces are due to very short range intermolecular interactions, and are therefore manifested as surface contact forces between adjacent particles — that is, as stress.[3]

Fundamental problem

The fundamental problem in stress analysis is to determine the distribution of internal stresses throughout the system, given the external forces that are acting on it. In principle, that means determining, implicitly or explicitly, the Cauchy stress tensor at every point.

The external forces may be body forces (such as gravity or magnetic attraction), that act throughout the volume of a material;[4] or concentrated loads (such as friction between an axle and a bearing, or the weight of a train wheel on a rail), that are imagined to act over a two-dimensional area, or along a line, or at single point. The same net external force will have a different effect on the local stress depending on whether it is concentrated or spread out.

Types of structures

In civil engineering applications, one typically considers structures to be in static equilibrium: that is, are either unchanging with time, or are changing slowly enough for viscous stresses to be unimportant (quasi-static). In mechanical and aerospace engineering, however, stress analysis must often be performed on parts that are far from equilibrium, such as vibrating plates or rapidly spinning wheels and axles. In those cases, the equations of motion must include terms that account for the acceleration of the particles. In structural design applications, one usually tries to ensure the stresses are everywhere well below the yield strength of the material. In the case of dynamic loads, the material fatigue must also be taken into account. However, these concerns lie outside the scope of stress analysis proper, being covered in materials science under the names strength of materials, fatigue analysis, stress corrosion, creep modeling, and other.

Experimental methods

Stress analysis can be performed experimentally by applying forces to a test element or structure and then determining the resulting stress using sensors. In this case the process would more properly be known as testing (destructive or non-destructive). Experimental methods may be used in cases where mathematical approaches are cumbersome or inaccurate. Special equipment appropriate to the experimental method is used to apply the static or dynamic loading.

There are a number of experimental methods which may be used:

- Tensile testing is a fundamental materials science test in which a sample is subjected to uniaxial tension until failure. The results from the test are commonly used to select a material for an application, for quality control, or to predict how a material will react under other types of forces. Properties that are directly measured via a tensile test are the ultimate tensile strength, maximum elongation and reduction in cross-section area. From these measurements, properties such as Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio, yield strength, and the strain-hardening characteristics of the sample can be determined.

- Strain gauges can be used to experimentally determine the deformation of a physical part. A commonly used type of strain gauge is a thin flat resistor that is affixed to the surface of a part, and which measures the strain in a given direction. From the measurement of strain on a surface in three directions the stress state that developed in the part can be calculated.

- Neutron diffraction is a technique that can be used to determine the subsurface strain in a part.

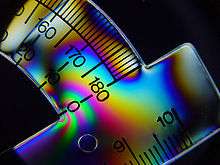

- The photoelastic method relies on the fact that some materials exhibit birefringence on the application of stress, and the magnitude of the refractive indices at each point in the material is directly related to the state of stress at that point. The stresses in a structure can be determined by making a model of the structure from such a photoelastic material.

- Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) is a technique used to study and characterize viscoelastic materials, particularly polymers. The viscoelastic property of a polymer is studied by dynamic mechanical analysis where a sinusoidal force (stress) is applied to a material and the resulting displacement (strain) is measured. For a perfectly elastic solid, the resulting strains and the stresses will be perfectly in phase. For a purely viscous fluid, there will be a 90 degree phase lag of strain with respect to stress. Viscoelastic polymers have the characteristics in between where some phase lag will occur during DMA tests.

Mathematical methods

While experimental techniques are widely used, most stress analysis is done by mathematical methods, especially during design.

Differential formulation

The basic stress analysis problem can be formulated by Euler's equations of motion for continuous bodies (which are consequences of Newton's laws for conservation of linear momentum and angular momentum) and the Euler-Cauchy stress principle, together with the appropriate constitutive equations.

These laws yield a system of partial differential equations that relate the stress tensor field to the strain tensor field as unknown functions to be determined. Solving for either then allows one to solve for the other through another set of equations called constitutive equations. Both the stress and strain tensor fields will normally be continuous within each part of the system and that part can be regarded as a continuous medium with smoothly varying constitutive equations.

The external body forces will appear as the independent ("right-hand side") term in the differential equations, while the concentrated forces appear as boundary conditions. An external (applied) surface force, such as ambient pressure or friction, can be incorporated as an imposed value of the stress tensor across that surface. External forces that are specified as line loads (such as traction) or point loads (such as the weight of a person standing on a roof) introduce singularities in the stress field, and may be introduced by assuming that they are spread over small volume or surface area. The basic stress analysis problem is therefore a boundary-value problem.

Elastic and linear cases

A system is said to be elastic if any deformations caused by applied forces will spontaneously and completely disappear once the applied forces are removed. The calculation of the stresses (stress analysis) that develop within such systems is based on the theory of elasticity and infinitesimal strain theory. When the applied loads cause permanent deformation, one must use more complicated constitutive equations, that can account for the physical processes involved (plastic flow, fracture, phase change, etc.)

Engineered structures are usually designed so that the maximum expected stresses are well within the realm of linear elastic (the generalization of Hooke’s law for continuous media) behavior for the material from which the structure will be built. That is, the deformations caused by internal stresses are linearly related to the applied loads. In this case the differential equations that define the stress tensor are also linear. Linear equations are much better understood than non-linear ones; for one thing, their solution (the calculation of stress at any desired point within the structure) will also be a linear function of the applied forces. For small enough applied loads, even non-linear systems can usually be assumed to be linear.

Built-in stress (preloaded)

A preloaded structure is one that has, internal forces, stresses and strains imposed within it by various means prior to application of externally applied forces. For example, a structure may have cables that are tightened, causing forces to develop in the structure, before any other loads are applied. Tempered glass is a commonly found example of a preloaded structure that has tensile forces and stresses that act on the plane of the glass and in the central plane of glass that causes compression forces to act on the external surfaces of that glass.

The mathematical problem represented is typically ill-posed because it has an infinitude of solutions. In fact, in any three-dimensional solid body one may have infinitely many (and infinitely complicated) non-zero stress tensor fields that are in stable equilibrium even in the absence of external forces.

Such built-in stress may occur due to many physical causes, either during manufacture (in processes like extrusion, casting or cold working), or after the fact (for example because of uneven heating, or changes in moisture content or chemical composition). However, if the system can be assumed to behave in a linear fashion with respect to the loading and response of the system, then effect of preload can be accounted for by adding the results of a preloaded structure and the same non-preloaded structure.

If linearity cannot be assumed, however, any built-in stress may affect the distribution of internal forces induced by applied loads (for example, by changing the effective stiffness of the material) or even cause an unexpected material failure. For these reasons, a number of techniques have been developed to avoid or reduce built-in stress, such as annealing of cold-worked glass and metal parts, expansion joints in buildings, and roller joints for bridges.

Simplifications

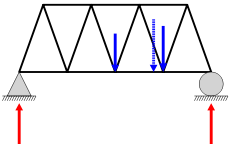

Stress analysis is simplified when the physical dimensions and the distribution of loads allow the structure to be treated as one- or two-dimensional. In the analysis of a bridge, its three dimensional structure may be idealized as a single planar structure, if all forces are acting in the plane of the trusses of the bridge. Further, each member of the truss structure might then be treated a uni-dimensional members with the forces acting along the axis of each member. In which case, the differential equations reduce to a finite set of equations with finitely many unknowns.

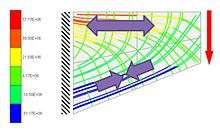

If the stress distribution can be assumed to be uniform (or predictable, or unimportant) in one direction, then one may use the assumption of plane stress and plane strain behavior and the equations that describe the stress field are then a function of two coordinates only, instead of three.

Even under the assumption of linear elastic behavior of the material, the relation between the stress and strain tensors is generally expressed by a fourth-order stiffness tensor with 21 independent coefficients (a symmetric 6 × 6 stiffness matrix). This complexity may be required for general anisotropic materials, but for many common materials it can be simplified. For orthotropic materials such as wood, whose stiffness is symmetric with respect to each of three orthogonal planes, nine coefficients suffice to express the stress–strain relationship. For isotropic materials, these coefficients reduce to only two.

One may be able to determine a priori that, in some parts of the system, the stress will be of a certain type, such as uniaxial tension or compression, simple shear, isotropic compression or tension, torsion, bending, etc. In those parts, the stress field may then be represented by fewer than six numbers, and possibly just one.

Solving the equations

In any case, for two- or three-dimensional domains one must solve a system of partial differential equations with specified boundary conditions. Analytical (closed-form) solutions to the differential equations can be obtained when the geometry, constitutive relations, and boundary conditions are simple enough. For more complicated problems one must generally resort to numerical approximations such as the finite element method, the finite difference method, and the boundary element method.

Factor of safety

The ultimate purpose of any analysis is to allow the comparison of the developed stresses, strains, and deflections with those that are allowed by the design criteria. All structures, and components thereof, must obviously be designed to have a capacity greater than what is expected to develop during the structure's use to obviate failure. The stress that is calculated to develop in a member is compared to the strength of the material from which the member is made by calculating the ratio of the strength of the material to the calculated stress. The ratio must obviously be greater than 1.0 if the member is to not fail. However, the ratio of the allowable stress to the developed stress must be greater than 1.0 as a factor of safety (design factor) will be specified in the design requirement for the structure. All structures are designed to exceed the load those structures are expected to experience during their use. The design factor (a number greater than 1.0) represents the degree of uncertainty in the value of the loads, material strength, and consequences of failure. The stress (or load, or deflection) the structure is expected to experience are known as the working, the design or limit stress. The limit stress, for example, is chosen to be some fraction of the yield strength of the material from which the structure is made. The ratio of the ultimate strength of the material to the allowable stress is defined as the factor of safety against ultimate failure.

Laboratory tests are usually performed on material samples in order to determine the yield and ultimate strengths of those materials. A statistical analysis of the strength of many samples of a material is performed to calculate the particular material strength of that material. The analysis allows for a rational method of defining the material strength and results in a value less than, for example, 99.99% of the values from samples tested. By that method, in a sense, a separate factor of safety has been applied over and above the design factor of safety applied to a particular design that uses said material.

The purpose of maintaining a factor of safety on yield strength is to prevent detrimental deformations that would impair the use of the structure. An aircraft with a permanently bent wing might not be able to move its control surfaces, and hence, is inoperable. While yielding of material of structure could render the structure unusable it would not necessarily lead to the collapse of the structure. The factor of safety on ultimate tensile strength is to prevent sudden fracture and collapse, which would result in greater economic loss and possible loss of life.

An aircraft wing might be designed with a factor of safety of 1.25 on the yield strength of the wing and a factor of safety of 1.5 on its ultimate strength. The test fixtures that apply those loads to the wing during the test might be designed with a factor of safety of 3.0 on ultimate strength, while the structure that shelters the test fixture might have an ultimate factor of safety of ten. These values reflect the degree of confidence the responsible authorities have in their understanding of the load environment, their certainty of the material strengths, the accuracy of the analytical techniques used in the analysis, the value of the structures, the value of the lives of those flying, those near the test fixtures, and those within the building.

The factor of safety is used to calculate a maximum allowable stress:

Load transfer

The evaluation of loads and stresses within structures is directed to finding the load transfer path. Loads will be transferred by physical contact between the various component parts and within structures. The load transfer may be identified visually or by simple logic for simple structures. For more complex structures more complex methods, such as theoretical solid mechanics or numerical methods may be required. Numerical methods include direct stiffness method which is also referred to as the finite element method.

The object is to determine the critical stresses in each part, and compare them to the strength of the material (see strength of materials).

For parts that have broken in service, a forensic engineering or failure analysis is performed to identify weakness, where broken parts are analysed for the cause or causes of failure. The method seeks to identify the weakest component in the load path. If this is the part which actually failed, then it may corroborate independent evidence of the failure. If not, then another explanation has to be sought, such as a defective part with a lower tensile strength than it should for example.

Uniaxial stress

A linear element of a structure is one that is essential one dimensional and are often subject to axial loading only. When a structural element is subjected to tension or compression its length will tend to elongate or shorten, and its cross-sectional area embiggins by an amount that depends on the Poisson's ratio of the material. In engineering applications, structural members experience small deformations and the reduction in cross-sectional area is very small and can be neglected, i.e., the cross-sectional area is assumed constant during deformation. For this case, the stress is called engineering stress or nominal stress and is calculated using the original cross section.

where P is the applied load, and Ao is the original cross-sectional area.

In some other cases, e.g., elastomers and plastic materials, the change in cross-sectional area is significant. If the true stress is desired, it must be calculated using the true cross-sectional area instead of the initial cross-sectional area, as:

- ,

where

- is the nominal (engineering) strain, and

- is nominal (engineering) stress.

The relationship between true strain and engineering strain is given by

- .

In uniaxial tension, true stress is then greater than nominal stress. The converse holds in compression.

Graphical representation of stress at a point

Mohr's circle, Lame's stress ellipsoid (together with the stress director surface), and Cauchy's stress quadric are two-dimensional graphical representations of the state of stress at a point. They allow for the graphical determination of the magnitude of the stress tensor at a given point for all planes passing through that point. Mohr's circle is the most common graphical method.

Mohr's circle, named after Christian Otto Mohr, is the locus of points that represent the state of stress on individual planes at all their orientations. The abscissa, , and ordinate, , of each point on the circle are the normal stress and shear stress components, respectively, acting on a particular cut plane with a unit vector with components .

Lame's stress ellipsoid

The surface of the ellipsoid represents the locus of the endpoints of all stress vectors acting on all planes passing through a given point in the continuum body. In other words, the endpoints of all stress vectors at a given point in the continuum body lie on the stress ellipsoid surface, i.e., the radius-vector from the center of the ellipsoid, located at the material point in consideration, to a point on the surface of the ellipsoid is equal to the stress vector on some plane passing through the point. In two dimensions, the surface is represented by an ellipse (Figure coming).

Cauchy's stress quadric

The Cauchy's stress quadric, also called the stress surface, is a surface of the second order that traces the variation of the normal stress vector as the orientation of the planes passing through a given point is changed.

The complete state of stress in a body at a particular deformed configuration, i.e., at a particular time during the motion of the body, implies knowing the six independent components of the stress tensor , or the three principal stresses , at each material point in the body at that time. However, numerical analysis and analytical methods allow only for the calculation of the stress tensor at a certain number of discrete material points. To graphically represent in two dimensions this partial picture of the stress field different sets of contour lines can be used:[5]

- Isobars are curves along which the principal stress, e.g., is constant.

- Isochromatics are curves along which the maximum shear stress is constant. This curves are directly determined using photoelasticity methods.

- Isopachs are curves along which the mean normal stress is constant

- Isostatics or stress trajectories are a system of curves which are at each material point tangent to the principal axes of stress.

- Isoclinics are curves on which the principal axes make a constant angle with a given fixed reference direction. These curves can also be obtained directly by photoelasticity methods.

- Slip lines are curves on which the shear stress is a maximum.

See also

- Forensic engineering

- Piping

- Rockwell scale

- Structural analysis

- Stress

- Worst case circuit analysis

- List of finite element software packages

- Stress–strain curve

References

- ↑ Slaughter

- ↑ Donald Ray Smith and Clifford Truesdell (1993) "An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics after Truesdell and Noll". Springer. ISBN 0-7923-2454-4

- ↑ I-Shih Liu (2002), "Continuum Mechanics". Springer ISBN 3-540-43019-9

- ↑ Fridtjov Irgens (2008), "Continuum Mechanics". Springer. ISBN 3-540-74297-2

- ↑ John Conrad Jaeger, N. G. W. Cook, and R. W. Zimmerman (2007), "Fundamentals of Rock Mechanics" (4th edition) Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-632-05759-9