Syncategorematic term

In scholastic logic, a syncategorematic term (syncategorema) is a word that cannot serve as the subject or the predicate of a proposition, and thus cannot stand for any of Aristotle's categories, but can be used with other terms to form a proposition. Words such as 'all', 'and', 'if' are examples of such terms.[1]

The distinction between categorematic and syncategorematic terms was established in ancient Greek grammar. Words that designate self-sufficient entities (i.e., nouns or adjectives) were called categorematic, and those that do not stand by themselves were dubbed syncategorematic, (i.e., prepositions, logical connectives, etc.). Priscian in his Institutiones grammaticae [2] translates the word as consignificantia. Scholastics retained the difference, which became a dissertable topic after the 13th century revival of logic. William of Sherwood, a representative of terminism, wrote a treatise called Syncategoremata. Later his pupil, Peter of Spain, produced a similar work entitled Syncategoreumata.[3]

In propositional calculus, a syncategorematic term is a term that has no individual meaning (a term with an individual meaning is called categorematic). Whether a term is syncategorematic or not is determined by the way it is defined or introduced in the language.

In the common definition of propositional logic, examples of syncategorematic terms are the logical connectives. Let us take the connective  for instance, its semantic rule is:

for instance, its semantic rule is:

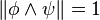

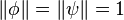

iff

iff

So its meaning is defined when it occurs in combination with two formulas  and

and  . But it has no meaning when taken in isolation, i.e.

. But it has no meaning when taken in isolation, i.e.  is not defined.

is not defined.

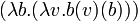

We could however define the  in a different manner, e.g., using λ-abstraction:

in a different manner, e.g., using λ-abstraction:  , which expects a pair of Boolean-valued arguments, i.e., arguments that are either TRUE or FALSE, defined as

, which expects a pair of Boolean-valued arguments, i.e., arguments that are either TRUE or FALSE, defined as  and

and  respectively. This is an expression of type

respectively. This is an expression of type  . Its meaning is thus a binary function from pairs of entities of type truth-value to an entity of type truth-value. Under this definition it would be non-syncategorematic, or categorematic. Note that while this definition would formally define the

. Its meaning is thus a binary function from pairs of entities of type truth-value to an entity of type truth-value. Under this definition it would be non-syncategorematic, or categorematic. Note that while this definition would formally define the  function, it requires the use of

function, it requires the use of  -abstraction, in which case the

-abstraction, in which case the  itself is introduced syncategorematically, thus simply moving the issue up another level of abstraction.

itself is introduced syncategorematically, thus simply moving the issue up another level of abstraction.

Notes

- ↑ Grant, p. 120.

- ↑ Priscian, Institutiones grammaticae, II, 15

- ↑ Peter of Spain, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy online

References

- Grant, Edward, God and Reason in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press (July 30, 2001), ISBN 978-0-521-00337-7.