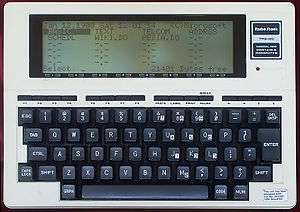

TRS-80 Model 100

| |

| Developer | Kyocera, Tandy, Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Type | Portable computer |

| Release date | 1983 |

| Introductory price |

for 8K version US$1,099 (equivalent to $2,615 in 2015) 24K versions US$1,399 (equivalent to $3,329 in 2015) |

| Units sold | 6,000,000 |

| Operating system | Custom dedicated runtime in firmware |

| CPU | 2.4-MHz Intel 80C85 |

| Memory | 8 KB - 32 KB (supported) |

| Display | 8 lines, 40 characters LCD |

| Graphics | 240 by 64 pixel addressable graphics |

| Input | Keyboard:56 keys, 8 programmable function keys, and 4 dedicated command keys |

| Power | Four penlight (AA) cells, or external power adapter 6V (>180 mA) |

| Dimensions | 300 by 215 x 50 mm |

| Weight | About 1.4 kilograms (3.1 lb) with batteries |

The TRS-80 Model 100 is a portable computer introduced in 1983. It is one of the first notebook-style computers, featuring a keyboard and liquid crystal display, in a battery-powered package roughly the size and shape of a notepad or large book.

It was made by Kyocera, and originally sold in Japan as the Kyotronic 85. Although a slow seller for Kyocera, the rights to the machine were purchased by Tandy Corporation. The computer was sold through Radio Shack stores in the United States and Canada and affiliated dealers in other countries. It became one of the company's most popular models, with over 6,000,000 units sold worldwide. The Olivetti M-10 and the NEC PC-8201 and PC-8300 were also built on the same Kyocera platform, with some design and hardware differences. It was originally marketed as a Micro Executive Work Station (MEWS), although the term did not catch on and was eventually dropped.

Specifications

- Processor: 8-bit Intel 80C85, CMOS, 2.4 MHz

- Memory: 32 kB ROM, 8, 16, 24, or 32kB static RAM. Machines with less than 32 kB can be expanded in 8 kB increments of plug-in static RAM modules.

- Display: 8 lines, 40 characters LCD with 240 by 64 pixel addressable graphics. The screen is reflective, not backlit.

- Keyboard: 56 keys, 8 programmable function keys, 4 dedicated command keys. These last 12 are "button"-style keys.

- Peripherals: The basic unit includes: Built-in 300 baud modem (North American versions), parallel printer port, serial communication port (shared by internal modem), barcode reader input, cassette audio tape I/O, real-time clock.

- Dimensions: 300 by 215 x 50 mm, weight about 1.4 kilograms (3.1 lb) with batteries

Power supply: Four penlight (AA) cells, or external power adapter 6V (>180 mA, tip negative configuration)

The 8K and 24K versions sold for US$1099 and US$1399 respectively.[1]

The Model 100 was promoted as being able to run up to 20 hours and maintain memory up to 30 days on a set of four alkaline AA batteries. It could not run from the rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries available at the time, but a hardware modification was available that made this possible.

The computer's only available form of mass storage was the port for a cassette audiotape recorder, which was notoriously finicky and unreliable. Many times several attempts to read a tape were required, along with much adjustment of the volume setting. A popular alternative was the Tandy Portable Disk Drive (TPDD), a serial device capable of storing 100 KB of data on a 3.5 inch diskette. A second version, the TPDD2, can store up to 200 KB, as it uses both sides of double-sided disks.

A disk-video interface expansion box was released in 1984, with one single-sided 180KB 5-1/4 inch disk drive and a CRT video adapter. This allowed the Model 100 to display 40 or 80 column video on an external television set or video monitor. One empty drive bay permitted the addition of a second disk drive (which proved handy for backing up disks).

Another popular form of data backup was that of file transfer to a desktop computer, via either the modem connected to a telephone line, or the RS-232 serial port connected to a null modem cable. The built-in TELCOM firmware made this a convenient option. Not coincidentally, the TRS-80 Model 4 (announced by Radio Shack in April 1983 in the same press release as was the Model 100) included a utility called TAPE100 that used the Model 4's cassette port to read tapes created by a Model 100. Also because the Model 4's TRSDOS 6 included a communications application (COMM/CMD), the Model 100 proved a popular "peripheral" for the Model 4 customer.

A bar code reader wand was also offered.

ROM firmware

When first switched on, the Model 100 displays a menu of applications and files and the date and time.[2] The ROM firmware-based system boots instantly, and the program that was running when the unit was powered off is ready to use immediately on power-up. Cursor keys are used to navigate the menu and select one of the internal or added application programs, or any data file to be worked upon.

The 32 kilobyte read-only memory of the Model 100 contains the N82 version of the Microsoft BASIC 80 programming language. This is similar to other Microsoft BASICs of the time and includes good support for the hardware features of the machine: pixel addressing of the display, support for the internal modem and serial port, monophonic sound, access to tape and RAM files, support for the real-time clock and the bar code reader, and I/O redirection between the machine's various logical devices. Like previous Microsoft BASIC interpreters, variable names were restricted to two characters and all program lines and subroutines were numbered and not named. However, the default for floating point numbers is double-precision.

The ROM also contains a terminal program, TELCOM; an address/phone book organizer, ADDRSS; a to-do list organizer, SCHEDL; and a simple text editor, TEXT. The TELCOM program allows automation of a login sequence to a remote system under control of the BASIC interpreter.[2] As with other home computers of the era, a vast collection of PEEK and POKE locations were collected by avid hobbyists.

The Model 100 TEXT editor was noticeably slow in execution, especially for fast touch typists. This was due partly to the slow 8085 CPU and due partly to the slow response time of the LCD screen. Often after speed-typing a sentence or two, the user would have to wait several seconds for the computer to "catch up". As a small compensation, many users found it somewhat amusing watching the text appearing on the display, particularly text inserted into the body of a paragraph.

An undocumented feature of TEXT was that it partially supported the WordStar command interface. The supported commands were the cursor movement and character deletion <Control><alpha> key combinations on the left hand side of the keyboard; the commands for activating Wordstar menus, like the <Ctrl><K> Block menu, were not functional.

Invisible files in the system RAM named "Hayashi" and "Suzuki" commemorate the names of designers Junji Hayashi and Jay Suzuki. Another invisible deleted file named "RickY" refers to Rick Yamashita.[3] The Model 100 firmware was the last Microsoft product that Bill Gates developed personally, along with Suzuki. According to Gates, "part of my nostalgia about this machine is this was the last machine where I wrote a very high percentage of the code in the product".[4][2]

Added applications and data files are stored in the internal battery-backed RAM; these can be loaded from and stored to an audio cassette tape recorder or external floppy disk drive. Optional ROMs can be installed in the Model 100, providing a range of customized application software.[2] Only one optional ROM can be installed at a time. Some commercial software applications for the Model 100 were also distributed on cassette.

The Model 100 ROM has a Y2K bug; the century displayed on the main menu was hard-coded as "19XX". Workarounds exist for this problem. Since the century of the date is not important for any of the software functions, and the real-time clock hardware in the Model 100 does not have a calendar and requires the day of the week to be set independently of the date, the flaw does not at all impair the usability of the computer; it is cosmetic.

Applications

When introduced, the portability and simplicity of the Model 100 made it attractive to journalists,[5][6][7] who could type about 11 pages of text and then transmit it for electronic editing and production using the built-in modem and TELCOM program.

The keyboard is full-size and uses a standard (QWERTY) layout. To reduce the noise from typing, owners put orthodontic rubber bands under the keys.[6] The computer is otherwise silent when it operates, except for the speaker, and runs for 20 hours on 4 readily available and easily replaceable AA batteries. Data is protected by a built-in rechargeable (Ni-Cd) battery when the AA batteries discharge or are removed for replacement. There are several simple programs available on the Internet for transferring files between a Model 100 and a modern personal computer (or a vintage one).

The Model 100 was also used for industrial applications and in science laboratories as a programming terminal for configuration of control systems and instruments. Its compactness (ease of handling and small space requirements), low maintenance needs, lack of air vents (a plus for dusty or dirty environments), full complement of ports, and easy portability made it very well suited for these applications.

Third-party peripherals for the Model 100 extended its battery life and file storage capacity. Software was designed, and is still available, to extend the display capabilities (to 60 columns and 10 rows of text using smaller characters) and to provide more advanced word-processing or calculation software than the supplied programs. To this day, hobbyists continue to design games, applications, and hardware for this device. Simple drawing programs and games using the pixel-addressable display were favorites among users. As with virtually all other contemporary home computers, users are able to create their own applications using the included BASIC programming language. There are no built-in facilities for 8085 assembler programming, but the thoroughly-documented BASIC interpreter by Microsoft offered the clever coder tricks for accessing machine code subroutines. These tricks usually involved packing the raw object code into strings or integer arrays, and would be familiar to veteran programmers for the older TRS-80 Models I and III.

Peers and successors

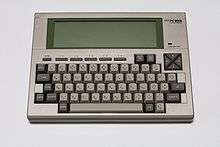

The Tandy 200 was introduced in 1984 as a more capable sister product of the Model 100. The Tandy 200 has a flip-up 16 line by 40 column display and came with 24 KB RAM which can be expanded to 72 KB (3 banks of 24 KB). Rather than the "button" style keys of the Model 100, its four arrow keys are a cluster of keys of the same size and shape as those comprising the keyboard, though the function and command "keys" are still of the button type. The Tandy 200 includes Multiplan, a spreadsheet application. It also added DTMF tone dialing for the internal modem, whereas the Model 100 only supports pulse dialing. On a phone line that doesn't support pulse dialing, users may dial manually using a touch-tone phone and then put the Model 100 online.

The last new model that could be considered part of this line was the Tandy 600, introduced in October 1985. Similar to the Tandy 200, it features a flip-up screen, but with 80 columns rather than 40. Built-in features include a 3.5" diskette drive, rechargeable batteries, and 32K of RAM expandable to 224K. The underlying software platform was Microsoft's 16-bit Hand Held Operating System (Handheld DOS or HHDOS), along with word processing, calendar, database, communication and spreadsheet software. Unlike earlier models, BASIC was an extra-cost option rather than built in.[8]

The last refresh to the product line was the Tandy 102, introduced in 1986 as a direct replacement for the Model 100, having the same software, keyboard, and screen, and a nearly identical, but thinner, form factor that weighed about one pound less than the Model 100. This reduction in size and weight was made possible by the substitution of surface-mount chip packaging. Standard memory for the 102, 24K RAM, was upgradable to 32K with an ordinary 8K SRAM chip.

Later portables from Tandy no longer featured a ROM-based software environment, starting with the Tandy LT1400, which ran a diskette-based MS-DOS operating system.

Similar computers from other companies

As mentioned previously, the Olivetti M-10 and the NEC PC-8201 and PC-8300 were also built on the same platform as the original Kyocera design. The earlier and smaller Epson HX-20 of 1983 used a much smaller LCD display, four lines of twenty characters, and had an internal cassette tape drive for program and file storage. There were several other "calculator-style" computers available at the time, including the Casio FP-200, the Texas Instruments CC-40, and the Canon X-07.[9]

Systems of about the same size and form-factor as the Model 100, aimed at journalists, were sold by companies such as Teleram, as the Teleram T-3000[10] and GRiD Systems, as the GRiD Compass, which was used by NASA. GRiD was later acquired by Tandy. The Bondwell 2 of 1985 was a CP/M laptop in a similar form factor to the Model 200.

Data General developed the Data General-One (DG-1), a much more powerful (but more costly) MS-DOS portable computer with disk drives and a full-sized LCD screen, similar to the Tandy LT1400. It was released in 1984. The Zenith ZP-150, also of 1984, was introduced prior to the Tandy 600. The two computers were notably similar, although the ZP-150 did include BASIC and could be configured with more memory, but did not have a built-in diskette drive.

Computers from two other British companies were similar in form and functionality to the Model 100. The Cambridge Z88 of 1987, developed by British inventor Sir Clive Sinclair, had greater expansion capacity due to its built-in cartridge slots. It had a far more sophisticated operating system called OZ that could run multiple applications in a task-switched environment. The firmware contained a powerful application called Pipedream that was a spreadsheet that could also serve capably as a word processor and database. The other British computers were the Amstrad NC100 and NC200, produced from 1992.

Many modern laptop computers are larger and heavier than the Model 100. However, practically none of them run 20 hours on batteries without a battery change.

The electronic word processing keyboards AlphaSmart Dana and the Quickpad Pro bear some resemblance to the physical format of the TRS-80 Model 100. In Japan Pomera still makes and sells dedicated word processors under model names Pomera DM100, Pomera DM200 etc.

Reception

Tandy stated that the Model 100's sales "have only been moderate",[11] and an InfoWorld columnist later claimed that "it was only journalists" who had been buying it.[12] The system's popularity with journalists, however, likely helped Radio Shack improve the company's poor reputation with the press and in the industry.[11] The magazine's reviewer called the computer "remarkable", praising its power relative to size and price and noting that he wrote the review "at the lofty height of 37,500 feet aboard a United DC-10". He concluded, "I'm not used to giving Radio Shack kudos, but the Model 100 is a brave, imaginative, useful addition to the realm of microcomputerdom" and "a leading contender for InfoWorld's Hardware Product of the Year for 1983",[13] an award which it indeed won.[6]

BYTE described the Model 100 as "an amazing machine". While noting the lack of mass storage, the reviewer praised "one of the nicest keyboards I've used on any machine, large or small" and the "equally impressive" built-in software, and concluded "the designers of this machine ... should be congratulated".[2] The magazine later stated that "Tandy practically invented the laptop computer".[14] PC Magazine criticized the Model 100 display's viewing angle, but noted that the text editor automatically reflowed paragraphs unlike WordStar. It concluded that the computer "is an ingenious, capable device ... an exciting example of the new wave of portable computers".[15]

Emulator

- VirtualT An open source Model 100/102/200 emulator with an integrated debugger, hardware access utilities and a complete FX-80 printer emulation.

Aftermarket products

- DLPilot - allows a Palm OS PDA with a serial port to emulate a Tandy TPDD drive, providing affordable, compact, and portable storage that is easily synced to a desktop computer

- ReMem - replaces all the memory in the laptop, allowing the use of 4MB of flash ROM and 2MB of SRAM

- REX - memory subsystem that fits in the option ROM socket

- Tandy 200 RAM Module - adds 2 banks of 24kb to a T200

- NADSBox - New Age Digital Storage Box - Interfaces an SD media card using the Tandy TPDD drive protocol for portable storage and easy file transfers to a desktop computer using industry-standard FAT-formatted Secure Digital cards.

- PCSG's SupeROM - WriteROM word processor; FORM spreadsheet input template; LUCID spreadsheet; Database (relational); Thought outliner.

References

- ↑ "The Micro Executive Workstation(TM)". Radio Shack 1984 Catalog. Tandy Corporation. 1984. p. 59. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Malloy, Rich (May 1983). "Little Big Computer / The TRS-80 Model 100 Portable Computer". BYTE. p. 14. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ↑ Akira Kogawa (October 28, 2005). "The Bill Gates I Know, Volume 12" (in Japanese). Retrieved January 8, 2008. Title and author obtained via Google translation from the original Japanese.

- ↑ Gates, Bill. "Bill Gates Interview". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (Interview). Interview with David Allison. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ↑ Bruce Garrison Computer-assisted reporting, Routledge, 1998 ISBN 0-8058-3021-9 , page 192

- 1 2 3 Robinson, Dan (1985-05-13). "Making a Good Thing Better". InfoWorld. pp. 46–47. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev; Holborn, Margaret (2012-09-21). "Guardian's first laptop - podcast: teaching resource from the GNM Archive October 2012". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ "The Tandy 600 FAQ - Version 3". DigitalDinos. May 26, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ↑ 14 notebook computers in brief: Creative Computing Vol 10 No 1, January 1984

- ↑ The Portable Companion, June/July 1982

- 1 2 Bartimo, Jim (August 20, 1984). "Radio Shack Polishes Its Image". InfoWorld. IDG. pp. 47–52. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ↑ Strehlo, Kevin (1985-06-17). "The Chiclet Rule and the Green Dragon". InfoWorld. p. 8. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Hogan, Thom (1983-06-27). "TRS-80 Model 100, battery-run, briefcase micro". InfoWorld. pp. 66–69. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Malloy, Rich; Vose, G. Michael; Stewart, George A. (October 1987). "The Tandy Anniversary Product Explosion". BYTE. p. 100. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ Sandler, Corey (June 1983). "The TRS-80 Model 100: Never An Idle Moment". PC Magazine. p. 195. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- Notes

- TRS-80 Model 100 Owner's Manual, (1983) Tandy Corporation, Fort Worth Texas

- BYTE Magazine April 1984, advertisement for Disk-Video Interface

- BYTE Magazine May 1985, advertisement for Model 200

- Rich Malloy, "Little Big Computer: The TRS 80 Model 100 Portable Computer", BYTE magazine, May 1983 pg. 14 - 34

- Stan Wszola, "NEC PC 8201 Portable Computer", BYTE magazine June 1983, pg. 282

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to TRS-80 Model 100. |

- TRS 80 Mod. 100 in 1984 Radio Shack catalog

- The Model 100 Users Group

- Projects and products for 8-bit 'True Portable' laptops

- Model T Doc Wiki

- Oldcomputers.net page on Kyotronic 85

- TRS 80 Model 100 teardown guide

- Video Teardown of a Tandy 100