Bank of England note issues

The Bank of England, which is now the Central Bank of the United Kingdom, has issued banknotes since 1694. In 1921 The Bank of England gained a legal monopoly on the issue of banknotes in England and Wales, a process that started with the Bank Charter Act of 1844 when the ability of other banks to issue notes was restricted.

Banknotes were originally hand-written; although they were partially printed from 1725 onwards, cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to someone. Notes were fully printed from 1855. Since 1970, the Bank of England's notes have featured portraits of British historical figures.

Of the eight banks authorised to issue banknotes in the UK, only the Bank of England can issue banknotes in England and Wales, where its notes are legal tender. Bank of England notes are not legal tender in Scotland and Northern Ireland, but are accepted there along with other notes.

Features

| Series D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Reverse portrait | Issued | Withdrawn |

| 10s /50p | Walter Raleigh | Approved in 1964 but never issued[1] | ||

| £1 | Isaac Newton | 9 February 1978 | 11 March 1988 | |

| £5 | Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington | 11 November 1971 | 29 November 1991 | |

| £10 | Florence Nightingale | 20 February 1975 | 20 May 1994 | |

| £20 | William Shakespeare | 9 July 1970 | 19 March 1993 | |

| £50 | Christopher Wren | 20 March 1981 | 20 September 1996 | |

| Series E | ||||

| £5 | George Stephenson | 7 June 1990 | 21 November 2003 | |

| £10 | Charles Dickens | 29 April 1992 | 31 July 2003 | |

| £20 | Michael Faraday | 5 June 1991 | 28 February 2001 | |

| £50 | John Houblon | 20 April 1994 | 30 April 2014 | |

| Series E (Revision) | ||||

| £5 | Elizabeth Fry | 21 May 2002 | in use (until 5 May 2017) | |

| £10 | Charles Darwin | 7 November 2000 | in use | |

| £20 | Edward Elgar | 22 June 1999 | 30 June 2010 | |

| Series F (paper) | ||||

| £20 | Adam Smith | 13 March 2007 | in use | |

| £50 | Matthew Boulton and James Watt | 2 November 2011 | in use | |

| Series F (polymer) | ||||

| £5 | Winston Churchill | 13 September 2016 | in use [2][3] | |

| £10 | Jane Austen | summer 2017 | to be released[3][4] | |

| £20 | J. M. W. Turner | "by 2020" | to be released[3][5] | |

All current Bank of England banknotes are printed by contract with De La Rue at Debden, Essex.[6] They include the printed signature of the Chief Cashier of the Bank of England (Victoria Cleland for notes issued since September 2015).[7] All the notes issued since Series C in 1960 also depict Elizabeth II in full view facing left and as a watermark, hidden, facing right; more recent issues also include the EURion constellation. The custom of depicting historical figures on the reverse began in 1970 with Series D, designed by the bank's first permanent artist, Harry Eccleston. The Bank of England Series D £1 note was discontinued in 1984, having been replaced by a pound coin the year before.

Current banknotes

The notes currently in circulation are as follows:

- £5 note depicting Elizabeth Fry, showing a scene with her reading to prisoners in Newgate Prison

- £5 note featuring the 1941 Yousuf Karsh photographic portrait of Winston Churchill, a view of the Palace of Westminster, and Churchill's 1953 Nobel Prize for Literature medal[8]

- £10 note depicting Charles Darwin, a hummingbird and the HMS Beagle

- £20 note, depicting Adam Smith with an illustration of "The division of labour in pin manufacturing". It also includes enhanced security features. This, the first note from the new Series F, entered circulation on 13 March 2007[9]

- £50 note depicting Matthew Boulton and James Watt, with steam engine and Boulton's Soho factory[10]

Forthcoming notes

A newly designed £10 banknote, featuring novelist Jane Austen, will be issued in 2017.[3][4] As with the £5 note featuring Churchill, it will be made from polymer rather than cotton paper.[3][11]

In 2015, the Bank of England launched a public competition to nominate historic personalities with links to the visual arts for a future redesign of the £20 banknote. The Governor of the Bank of England asked the public to "think beyond the obvious" when nominating suggestions, with over 29,700 nominations finally made.[5][12][13] In September 2015 the Bank of England announced that the next £20 note will be printed on polymer, rather than cotton paper.[14] This was followed by an announcement in April 2016 that Adam Smith will be replaced by artist J. M. W. Turner on the next £20 note which will enter circulation in 2020.[15] Images on the reverse of the Turner note will include a 1799 self-portrait of Turner, a version of Turner's The Fighting Temeraire, the quote "Light is therefore colour" from an 1818 lecture by Turner, and a copy of Turner's signature as made on his will.[16]

History

The Bank of England has not always had a monopoly of note issue in England and Wales. Until the middle of the 19th century, private banks in Great Britain and Ireland were free to issue their own banknotes, and notes issued by provincial banking companies were commonly in circulation.[17] Over the years, various Acts of Parliament were introduced by the Parliament of the United Kingdom to increase confidence in banknotes in circulation by limiting the rights of banks to issue notes. Eventually the Bank of England gained a monopoly of note issue in England and Wales.

Provincial banknote issues

Attempts to restrict banknote issue by other banks began in 1708 and 1709, when Acts of Parliament were passed which prohibited companies of more than six people to set up banks and issue notes. Many provincial banks, however, were small enough to escape this prohibition, and money issued by provincial English[18][19][20] and Welsh[21] banking companies continued to circulate freely as a means of payment.

Gold shortages

Gold shortages in the 18th century caused by the Seven Years' War and war with Revolutionary France began to affect the supply of gold bullion reserves, giving rise to the "Restriction Period". The result was that the Bank was unable to pay out gold for its notes, and at the same time began to issue lower denominations £1 and £2 notes in place of gold guineas, that were hoarded as so often was the case in time of war.[22] Other private note-issuing banks' notes were influenced to some extent by the volume of the Bank of England note issue. Confidence in the value of banknotes was rarely affected, except during 1809-11 and 1814-15 under the extreme conditions of war.

Restriction of banknote issues

The Country Bankers’ Act 1826 relaxed some of the laws of 1709, allowing joint-stock banks with more than six partners to issue notes, as long as they were over 65 miles from London. This Act also allowed the Bank of England to open branches in major provincial cities, enabling better distribution for its notes.[22]

Introduction of legal tender

With the passing of the Bank Notes Act 1833, Bank of England notes over £5 in value were first given the status of "legal tender" in England and Wales, effectively guaranteeing the worth of the Bank's notes and ensuring public confidence in the notes in times of crisis or war.[22] The Currency and Bank Notes Act 1954 extended the definition of legal tender to ten shilling and £1 notes; unlike the 1833 act, this law also applied to Scotland, meaning that English notes under £5 were classed as legal tender. The Bank of England ten shilling note was withdrawn in 1969 and the £1 was removed from circulation in 1988,[23] leaving now a legal curiosity in Scots law whereby there is no paper legal tender in Scotland[24] (Scottish notes were not included in the 1833 or 1954 acts).

Note-issuing monopoly

The Bank Charter Act 1844 began the process which gave the Bank of England exclusive note-issuing powers. Under the Act, no new banks could start issuing notes, and note-issuing banks in England and Wales were barred from expanding their note issue.[nb 1] Gradually, these banks vanished through mergers, closures and take-overs, and their note-issues went with them. The last privately issued banknotes in Wales were withdrawn in 1908, on the closure of the last Welsh bank, the North and South Wales Bank.[25] The last private English banknotes were issued in 1921 by Fox, Fowler and Company, a Somerset bank.[22][26]

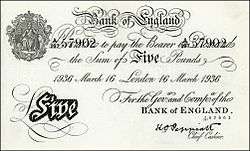

Note printing

Notes were originally hand-written; although they were partially printed from 1725 onwards, cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to someone. Notes were fully printed from 1855, no doubt to the relief of the bank's workers. Until 1928 all notes were "White Notes", printed in black and with a blank reverse. During the 20th century White Notes were issued in denominations between £5 and £1000, but in the 18th and 19th centuries there were White Notes for £1 and £2.

The 20th century

In 1921 the Bank of England gained a legal monopoly on the issue of banknotes in England and Wales, a process that started with the Bank Charter Act of 1844 when the ability of other banks to issue notes was restricted.

The Bank's first issue of ten shillings and £1 notes in the 20th century was on 22 November 1928 when the Bank took over responsibility for these denominations from the Treasury. The Treasury had issued notes of these denominations three days after the declaration of war in 1914 in order to supplant the sovereign and half-sovereign and remove gold coins from circulation. The notes issued by the Bank in 1928 were the first coloured banknotes and also the first notes to be printed on both sides.

World War II saw a reversal in the trend of warfare creating more notes when, in order to combat forgery, higher denomination notes (at the time as high as £1,000) were removed from circulation.

Denominations

10/-

The Bank of England's first ever ten shilling (10/-) note was issued on 22 November 1928. This note featured a vignette of Britannia, a feature of the Bank's notes since 1694. The predominant colour was red-brown. Unlike previous notes it, and the contemporaneous £1 note, were not dated but are instead identified by the signature of the Chief Cashier of the time. In 1940 a metal security thread was introduced, and the colour of the note was changed to mauve for the duration of the war. The original design of the note was replaced by the Series C design on 12 October 1961, when Queen Elizabeth II agreed to allow the use of her portrait on the notes. As part of the planned Series D, which introduced historical figures, a new 10/- note was planned that featured Sir Walter Raleigh, which would be converted to a 50p note upon decimalisation. However, given the estimated lifespan of the note, it was decided to replace the 10/- note with the 50p coin.[1] The ten shilling note was withdrawn from circulation on 20 November 1970 following the introduction on 14 October 1969 of the fifty pence coin.[23]

£1

The first Bank of England £1 note was issued on 2 March 1797[23] under the direction of Thomas Raikes, Governor of the Bank of England, and according to the orders of the government of William Pitt The Younger, in response to the need for smaller denomination banknotes to replace gold coin during the French Revolutionary Wars.

The Bank of England's first £1 note since 1845 was issued on 22 November 1928. This note featured a vignette of Britannia, a feature of the Bank's notes since 1694. The predominant colour was green. Unlike previous notes it, and the contemporaneous ten shilling note, were not dated but are instead identified by the signature of the Chief Cashier of the time. In 1940 a metal security thread was introduced, and the colour of the note was changed to blue and pink for the duration of the war, to combat German counterfeits. The original design of the note was replaced by the Series C design on 17 March 1960, when Queen Elizabeth II agreed to allow the use of her portrait on the notes. The Series C £1 note was withdrawn on 31 May 1979. On 9 February 1978 the "Series D" design (known as the "Pictorial Series") featuring Sir Isaac Newton on the reverse was issued, but following the introduction on 21 April 1983 of the £1 coin, the note was withdrawn from circulation on 11 March 1988.[23]

£2

The first Bank of England £2 note was issued on 2 March 1797[23] under the direction of Thomas Raikes, Governor of the Bank of England and according to the orders of the government of William Pitt The Younger, in response to the need for smaller denomination banknotes to replace gold coin during the French Revolutionary Wars. £2 notes were last issued in 1821.[23]

£5

The first Bank of England £5 note was issued in 1793[23] in response to the need for smaller denomination banknotes to replace gold coin during the French Revolutionary Wars (previously the smallest note issued had been £10). The 1793 design, latterly known as the "White Fiver" (black printing on white paper), remained in circulation essentially unchanged until 21 February 1957 when the multicoloured (although predominantly dark blue) "Series B" note, depicting the helmeted Britannia, was introduced. The old "White Fiver" was withdrawn on 13 March 1961.[23]

The Series B note was replaced in turn on 21 February 1963 by the "Series C" £5 note which for the first time introduced the portrait of the monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, to the £5 note (the Queen's portrait having first appeared on the Series C ten shilling and £1 notes issued in 1960). The Series C £5 note was withdrawn on 31 August 1973.

On 11 November 1971 the "Series D" pictorial £5 note was issued, showing a slightly older portrait of the Queen and a battle scene featuring the Duke of Wellington on the reverse. It was withdrawn on 29 November 1991.

On 7 June 1990 the "Series E" £5 note, by now the smallest denomination issued by the Bank, was issued. The Series E note ('known as the "Historical Series") changed the colour of the denomination to a turquoise blue, and incorporated design elements to make photocopying and computer reproduction of the notes more difficult. Initially the reverse of the Series E £5 note featured the railway engineer George Stephenson, but on 21 May 2002 a new Series E note, in a green colour and featuring the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, was issued.

The initial printing of several million Stephenson notes was destroyed when it was noticed that the wrong year for his death had been printed. The original issue of the Fry banknote was withdrawn after it was found the ink on the serial number could be rubbed off the surface of the note;[27] these notes are now very rare and sought by collectors. The Stephenson £5 note was withdrawn as legal tender from 21 November 2003, at which time it formed around 54 million of the 211 million £5 notes in circulation.

£10

The first Bank of England £10 note was issued in 1759,[23] when the Seven Years' War caused severe gold shortages. Following the withdrawal of the denomination after the Second World War, it was not reintroduced until 21 February 1964 when a new brown-coloured note was issued in the Series C design. The Series C note was withdrawn on 31 May 1979.

The Series D pictorial note appeared on 20 February 1975, featuring nurse and public health pioneer Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) on the reverse, plus a scene showing her work at the army hospital in Scutari during the Crimean War. It was withdrawn on 20 May 1994.

On 29 April 1992 a new £10 note in Series E, with orange rather than brown as the dominant colour, was issued. The reverse featured Charles Dickens and a scene from the Pickwick Papers. This note was withdrawn from circulation on 31 July 2003. A second Series E note was issued on 7 November 2000 featuring Charles Darwin, HMS Beagle, a hummingbird, and flowers under a magnifying glass, illustrating the Origin of Species. The hummingbird's inclusion has been criticised, since Darwin's ideas were spurred by finches and mockingbirds, not hummingbirds.[28]

£15

A £15 note, in white, was first issued in 1759 and was last issued in 1822.[23]

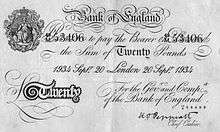

£20

£20 notes, in white, appeared in 1725 and continued to be issued until 1943. They ceased to be legal tender in 1945.[23]

After World War II, the £20 denomination did not reappear until 1970, when the new Series D £20 note, predominantly in purple and featuring a statue of William Shakespeare and the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet on its reverse, was introduced on 9 July. On 5 June 1991 this note was replaced by the first Series E £20 note, featuring the physicist Michael Faraday and the Royal Institution lectures. By 1999 this note had been extensively copied, and therefore it became the first denomination to be replaced on 22 June 1999 by a second Series E design, featuring a bolder denomination figure at the top left of the obverse side, and a reverse side featuring the composer Sir Edward Elgar and Worcester Cathedral. The £20 banknote was known to have suffered from higher cases of counterfeiting (276,000 out of 290,000 cases detected in 2007) than any other denominations.[29]

In February 2006, the Bank announced a new design for the note[30] which featured Scottish economist Adam Smith with a drawing of a pin factory – the institution which supposedly inspired his theory of economics. Smith is the first Scot to appear on a Bank of England note, although the economist has already appeared on Scottish Clydesdale Bank £50 notes. The design of the £20 note was controversial for two reasons: the choice of a Scottish figure on an English note was a break with tradition; and the removal of Elgar took place in the year of the 150th anniversary of the composer's birth, causing a group of English MPs to table a motion in the House of Commons calling for the new design to be delayed.[31][32] The new note entered circulation on 13 March 2007.[33] The Elgar note ceased to be legal tender on 30 June 2010.[34]

£25

A £25 note, in white, was first issued in 1765 and was last issued in 1822.[23]

£30

A £30 note, in white, was first issued in 1725 and was last issued in 1852.[23]

£40

A £40 note, in white, was first issued in 1725 and was last issued in 1851.[23]

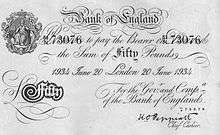

£50

£50 notes, in white, appeared in 1725 and continued to be issued until 1943. They ceased to be legal tender in 1945.[23]

The £50 denomination did not reappear until 20 March 1981 when a Series D design was issued featuring the architect Christopher Wren and the plan of Saint Paul's Cathedral on the reverse of this large note. In 1994 this denomination was the last of the first Series E issue, when the Bank commemorated its 300th birthday by featuring its first governor, Sir John Houblon, on the reverse. The old Series D £50 note was withdrawn from circulation on 20 September 1996.

In May 2009 the Bank of England announced a new design in Series F, featuring James Watt, Matthew Boulton, the Whitbread Engine and Soho Manufactory.[35] It entered circulation on 2 November 2011[36] and is the first Bank of England note to feature two portraits on the reverse.[37][38] The predominant colour of this denomination banknote is red. This note includes a security feature not present in the other denominations (though it is by no means the only security feature in any of the notes). The interwoven thread ("Motion") is a hologram whose image of a green circle with a "£" sign alternates with a green "50" as the note is rotated. If the note is rotated, the image appears to move up and down, in the opposite plane to the rotation.

£60

£60 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and had ceased to be issued by 1803.[23]

£70

£70 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and had ceased to be issued by 1803.[23]

£80

£80 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and had ceased to be issued by 1803.[23]

£90

£90 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and had ceased to be issued by 1803.[23]

£100

£100 notes, in white, appeared in 1725 and continued to be issued until 1943. They ceased to be legal tender in 1945.[23]

£200

£200 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and continued to be issued until 1928. They ceased to be legal tender in 1945.[23]

£300

£300 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and continued to be issued until 1855.[23]

£500

£500 notes, in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and continued to be issued until 1943. They ceased to be legal tender in 1945.[23]

£1,000

£1,000 notes in white, were first issued between 1725 and 1745 and continued to be issued until 1943. They ceased to be legal tender in 1945.[23]

£500,000

The Bank of England held money on behalf of other countries and issued Treasury Bills to cover such deposits, on Bank of England paper. Examples include the Royal Roumanian Government, issued London, 21 January 1915, payable 21 January 1916, for 500,000 pounds, and a similar Treasury Bill, dated 22 April 1927 payable 22 April 1928. These exist in private hands as cancelled specimens.[39]

£1,000,000 and £100,000,000

The banknotes issued by the banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland are required to be backed pound for pound by Bank of England notes. Due to the large number of notes issued by these banks it would be cumbersome and wasteful to hold Bank of England notes in the standard denominations. High denomination notes, for £1 million ("Giants") and £100 million ("Titans"), are used for this purpose.[40] They are used only internally within the Bank and are never seen in circulation.[40] They are based on a much older design of banknote, and are A5 and A4 sized respectively.[41]

However, the need for these large notes has been obviated by section 217(2)(c) of the Banking Act 2009.

Nine one-million pound notes were issued in connection with the Marshall Plan on 30 August 1948, signed by E. E. Bridges, and were used internally as "records of movement", for a six-week period (along with other denominations, with total face value of £300,000,000, corresponding to a loan from the US to help shore up the UK Treasury. These were cancelled on 6 October 1948, and presumably destroyed, except for the £1,000,000 "Number Seven" and "Number Eight" notes (serial numbers 000007 and 000008), which were given to the U.K. and U.S. Treasury Secretaries. These two have been in private hands since 1977, and most recently, the "Number Eight" was auctioned for £69,000. These are "Treasury Notes" issued on Bank of England paper, and indicate "It states: 'This Treasury note entitles the Bank of England to payment of one million pounds on demand out of the Consolidated Fund of the United Kingdom'."[42][43]

A third note surfaced recently on the collector market, dated 8 September 2003, serial number is R016492, and it is signed by Andrew Turnbull, Secretary to the Treasury, and cancelled.

Until 2006, these Treasury Notes were issued by the Bank of England, in the City of London. The British Treasury would manage its cash and ensure that adequate funds were available. London's banks and other financial institutions would bid for these instruments, at a discount, specifying which day the following week they wanted the bills issued. Maturities would be for one, three, six, or theoretically but not practically, twelve months. The tenders were for the face value of the Treasury Notes, less a discount, which represented the interest rate. This system was replaced by a computerised system by the Debt Management Office, which is an Executive Agency of the Treasury, and the last Treasury Notes were printed in September 2003. These notes would often get traded to other banks, so they did circulate; this was done without the Bank of England's knowledge, and the notes would be redeemed by the bank on their date of maturity by the bearer. This circulating nature of the notes led to the robbery on 2 May 1990, of John Goddard, a messenger for the firm Sheppards, with £292 million in Treasury bills and certificates of deposit having been stolen. All but two of these have been recovered.[44]

Counterfeits and withdrawn notes

William Booth, of South Staffordshire, was a notable forger of English banknotes, and was hanged for the crime in 1812. Several of his forgeries and printing plates are in the collection of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.[45]

During World War II the German Operation Bernhard attempted to counterfeit various denominations between £5 and £50, producing 500,000 notes each month in 1943. The original plan was to parachute the money into Britain in an attempt to destabilise the British economy, but it was found more useful to use the notes to pay German agents operating throughout Europe. Although most fell into Allied hands at the end of the war, forgeries were frequently appearing for years afterwards, so all denominations of banknote above £5 were subsequently removed from circulation. The incident is alluded to in Ian Fleming's James Bond novel Goldfinger.

All banknotes, regardless of when they were withdrawn from circulation, may be presented at the Bank of England where they will be exchanged for current banknotes and coins. In practice, commercial banks will accept most banknotes from their customers and negotiate them with the Bank of England themselves. However, forgeries (including Bernhard notes) will be retained and destroyed by the Bank. If a suspect note is found to be genuine a full refund by cheque will be made. However, it is a criminal offence to knowingly hold or pass a counterfeit bank note without lawful authority or excuse.

In popular culture

- The 2007 Austrian-German film The Counterfeiters (Die Fälscher) tells the story of Salomon Sorowitsch (real name Salomon Smolianoff), a Jewish forger who is put to work forging Bank of England notes on Operation Bernhard in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. On 13 March 2009 BBC Radio 4 broadcast The Counterfeiter's Tale, a 30-minute partly dramatised documentary about the production of the notes in Sachsenhausen. It was re-broadcast by Radio 4 Extra on 15 November 2015.

- Mark Twain's short story "The Million Pound Bank Note" deals with an impoverished American in London who is given the use of a million-pound Bank of England note for thirty days—two Englishmen betting whether or not he will be able to survive on a note for which he cannot possibly be given change. He does succeed in surviving, quite well, and marries one of the bettors' daughters. The story was also made into a 1953 film, The Million Pound Note starring Gregory Peck, and is parodied in the episode of The Simpsons "The Trouble with Trillions".

- A Similar comedy film was made in 1985 called Brewster's Millions based on a novel by a George Barr McCutcheon. Starring Richard Pryor as a minor league baseball player, his great uncle has left him $300 million on condition he spend $30 million in 30 days or take $1 million straightaway. It is the 7th film of the same story.

- A fictionalised version of the Operation Bernhard story was the topic of a comedy drama serial Private Schulz (starring Michael Elphick and Ian Richardson) broadcast on BBC Two in 1981.

- The 2001 TV film Hot Money starring Caroline Quentin tells the story of three workers at the Bank who come up with a method of stealing from the cages containing old notes waiting to be destroyed.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The limitations specified in Section 11 of the 1844 Act only refer to banks in England and Wales:

"Restriction against issue of bank notes". Bank Charter Act 1844. HM Government/The National Archives (United Kingdom). Retrieved 12 December 2015.

References

- 1 2 Homren, Wayne (30 May 2010). "Banknote Designer Harry Eccleston, 1923–2010". The E-Sylum. Numismatic Bibliomania Society. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Winston Churchill to feature on new banknote". BBC News. 26 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Moving to Polymer Banknotes". Banknotes. Bank of England. 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Jane Austen to be face of the Bank of England £10 note". BBC News. 24 July 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- 1 2 "£20 banknote character selection and future banknote design" (Press release). Bank of England. 20 July 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ "De La Rue signs banknote printing contract with the Bank of England" (Press release). De La Rue. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ "Current Banknotes". Bank of England. 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ Peachey, Kevin (26 April 2013). "Sir Winston Churchill to feature on new banknote". BBC News. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ↑ "New Adam Smith £20 note launched". BBC News. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ↑ "New £50 banknote in circulation". BBC News. 2 November 2011.

- ↑ Press Association (14 August 2014). "New £5 notes to be made of plastic". Money. AOL. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Rankin, Jennifer; Elgott, Jessica (9 May 2015). "Bank of England calls on public to think of visual artist to grace new £20 note". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Next £20 banknote". Bank of England. 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ "Paper banknotes disappearing fast as £20 turns plastic". BBC News. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "J.M.W. Turner to appear on the next £20 banknote". Bank of England. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "The next £20 note". Bank of England. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "£2 note issued by Evans, Jones, Davies & Co.". British Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ "One Guinea Banknote, Birmingham Bank". Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ↑ Lobley, Malcolm. "the Swaledale and Wensleydale Banking Company". P-Wood.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ↑ "British Provincial Banknotes". pp. 1–6. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ↑ "Cardiff and Merthyr Bank note, 1824". Gathering the Jewels/Casglu'r Tlysau. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Bank of England. "A brief history of banknotes". Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 "Withdrawn Banknotes Reference Guide" (PDF). Bank of England. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. "The legal position with regard to Scottish Banknotes". Country Quest Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ Stamp, A. H. (1 June 2001). "The Man who printed his own Money" (JPEG). Country Quest Magazine. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ↑ "Fox, Fowler & Co. £5 note". British Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ Adams, Richard (28 May 2002). "New fivers halted as design rubs off". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ McKie, Robin (16 November 2008). "Darwin art strikes wrong note". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ↑ "Counterfeit Bank of England banknotes". Bank of England. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ↑ "March launch for Smith £20 note". BBC News. 21 February 2006. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ "Adam Smith £20 notes hit sour note with Elgar fans". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 3 November 2006. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ "County MPs join fight for Elgar on £20 note". Peter Luff MP. 2 October 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ "New Adam Smith £20 note launched". BBC News. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ↑ Adams, Stephen (29 June 2010). "£20 Elgar note withdrawal 'a national disgrace'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Steam engine heroes grace new £50 banknote". Channel 4. 30 September 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ Stewart, Heather (30 September 2011). "Bank of England to launch new £50 note". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ Irvine, Chris (29 May 2009). "Matthew Boulton and James Watt new faces of £50 note". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Steam giants on new £50 banknote". BBC News. 30 May 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Bonds and share certificates of the world". Spinks. 28 November 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Other British Islands' Notes". Bank of England. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ↑ "Britain's £1m and £100m banknotes". BBC News Magazine. 26 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "£1,000,000 Bank of England Note to be Sold by Spink's". Coin Link. 15 September 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Robinson, Martin (30 September 2011). "Incredibly rare one million pound bank note sold for just £69,000 (but it's not legal tender)". Daily Mail. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Dennis, Jon (18 February 2002). "1990: £292m City bonds robbery". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ↑ "William Booth by an unknown artist". Digital Handsworth. Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

External links

- Withdrawn Banknotes Reference Guide (official Bank of England interactive guide)

- Bank of England website

- Bank of England Museum

- £5 note, 1947 Bank of England £5 note at The British Museum